KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Tuesday night’s primary results generally showed Joe Biden running stronger versus Bernie Sanders than Hillary Clinton did against Sanders four years ago.

— Biden won every single county in Michigan, Mississippi, and Missouri, and he performed more than well enough out West.

— Biden’s delegate lead is expanding, and should continue to next Tuesday.

Biden takes command

Tuesday night’s Democratic presidential primary results were the equivalent of a diner motioning across the restaurant to a waiter and mouthing two words: “Check, please.”

While a significant chunk of the party supports Bernie Sanders in his head-to-head matchup with Joe Biden, a considerably larger portion backs Biden. The size of that larger group is indicative of a party that is ready to move on to the general election against Donald Trump.

Biden’s smashing victories in Michigan, Mississippi, and Missouri were so total that Sanders did not win a single county in any of the three states.

Washington state is basically tied, with Sanders up a couple tenths of a percentage point, as mail-in ballots trickle in. There are about a million votes in, which we suspect is substantially more than half of the total votes even if turnout is very high. The eventual delegate edge that the winning candidate gets when it’s all said and done will end up being relatively negligible. The Biden campaign is surely comfortable with that outcome given that Sanders won other western states California, Colorado, and Utah last week. Biden won Washington’s eastern neighbor, Idaho, while Sanders won North Dakota.

In this newly-consolidated two-person race, Biden appears stronger than Hillary Clinton four years ago, and Sanders weaker than his previous incarnation. In Michigan amidst significantly higher turnout — close to 1.6 million ballots cast this time as opposed to just about 1.2 million last time — Biden got more votes than Clinton in every single county, while Sanders ran behind his vote total in 70 of 83 counties, per Michigan reporter Jonathan Oosting (these figures may change as the vote is finalized: Michigan is using a hugely-expanded absentee balloting system for this election).

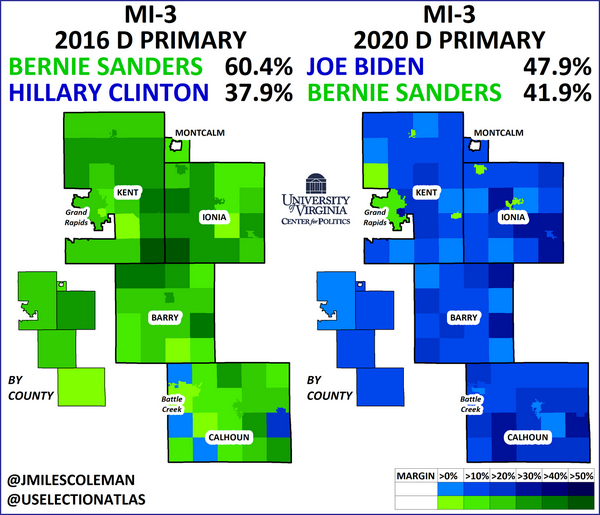

MI-3, a Republican-leaning congressional district represented by Republican-turned-independent Rep. Justin Amash, covers most of Grand Rapids’ Kent County and other parts of western Michigan. The trend there helps to demonstrate what happened statewide (Map 1). This was Sanders’ best district in the state against Clinton in 2016; Biden ended up carrying it this time amidst significantly higher turnout (close to 110,000 total votes, up from about 75,000 four years ago).

Map 1: Democratic primary results, MI-3, 2016 vs. 2020

There were some bright spots for Sanders: It appears that he did better than four years ago, for instance, in both the city of Detroit and East Lansing (home of Michigan State University), but the negative trends far outweighed the positive ones: no surprise when a narrow victory four years ago turns into a 15-plus point defeat.

The focus on Michigan took attention away from Missouri, which Clinton only won by .25 points over Sanders in 2016. Biden pushed the decimal point two places to the right, winning by 25 points. Biden’s domination of the state was thorough: He even carried Boone County (Columbia), home of the University of Missouri, albeit just by six points (Sanders, then and now a favorite of younger and collegiate voters, won the county by 22 points four years ago).

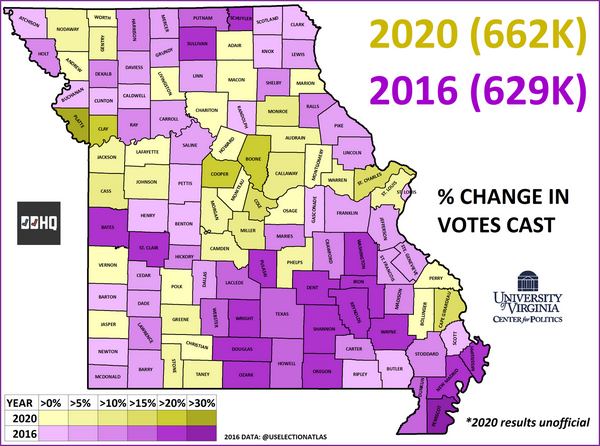

Missouri’s turnout was only up a little bit from 2016, more than 660,000 votes this time compared to about 630,000 four years ago, a modest change compared to some other states. This is perhaps unsurprising in a state that has transitioned from competitive to safe Republican over the past couple of decades. Of 114 counties, 72 saw turnout drops (Map 2), with vast swaths of the northern and southeastern parts of the state seeing a drop. This is indicative of the weakening Democratic brand in rural parts of the state, something that has become obvious in recent statewide general elections, too. Meanwhile, some counties close to the state’s major urban centers, Kansas City in the west and St. Louis in the east, saw turnout increases. This is suggestive of the broader trend of increased Democratic engagement in suburban areas across the country.

Map 2: Missouri Democratic primary turnout changes, 2016 vs. 2020

Mississippi was very similar to four years ago overall: The state with the nation’s most heavily African-American primary electorate voted 82%-17% for Clinton and 81%-15% for Biden. Technically, the most recent reporting has Sanders at 14.8% in Mississippi — that is important for delegate-counting, because if he remains under 15%, he won’t get any statewide delegates. Regardless, Mississippi suggests Biden will enjoy landslides in the two remaining Deep South states that have not yet voted: Georgia on March 24 and Louisiana on April 4.

There are no signs things will get better for Sanders next week, when four more large states vote: Arizona, Florida, Illinois, and Ohio. Sanders has never shown any strength in Florida, and Biden should rout him there. Sanders lost Illinois narrowly and Ohio not-so-narrowly in 2016. Biden’s sweep of both Michigan and Missouri’s counties suggests we should expect something similar in their regional neighbors. Sanders carried much of downstate Illinois and also some of the Chicago collar counties in 2016. The results so far this year suggest he won’t replicate that. Sanders has done better out West, and he has also done well with Hispanic voters, which gives him a glimmer of hope in Arizona. But Arizona also has a lot of older voters and well-off suburbanites, high-turnout groups that have been flocking to Biden.

Biden’s delegate lead is increasing. As of Monday night, he was up 608 to 532 in our Crystal Ball/Decision Desk HQ count; that is now 777 to 636. So Biden’s lead has nearly doubled, going from 76 to 141. Based on proportional allocation rules, the only way for Sanders to really gain ground is to win lopsided victories in big states. But the opposite seems likely to occur next week.

Perhaps Sanders can hold out to try to score a victory in Wisconsin on April 7, a state with a liberal Democratic electorate where he won decisively in 2016. But at this rate, Biden is probably favored there too, given that he won Michigan and Minnesota, two states similar to Wisconsin, after Sanders carried them in 2016. And even if Sanders were to win Wisconsin, what would that really get him? Sanders also is disadvantaged by the nation’s public health crisis, which limits his ability to campaign and hold the big rallies that have defined his campaign both this cycle and last.

Yes, there is a debate scheduled for Sunday night. Biden, a shaky performer, could fall on his face and give Democrats buyer’s remorse.

But the cushion Biden has built, and will add to, is getting so large that Sanders can’t reasonably hope to catch up. Over the past two Tuesdays, states that possess more than 40% of the total pledged delegates have spoken. Next Tuesday, four more states with 15% of the delegates will amplify, in all likelihood, the message from those states: The Democrats have seen enough, and they prefer Biden to Sanders.