KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Demographic changes in Kansas have caused the state to trend leftwards, as Republicans’ hold on the state’s metro areas has waned.

— It remains to be seen whether these trends have moved the state into a position where Democratic candidates can be competitive at the federal level.

— Democrats may have an opening with this year’s Senate race, but the crucial voters they need to win may not be where many think they are.

— In a close election, regional turnout patterns could be the deciding factor.

Suburban trends illustrate new alliances in Kansas

Between the 2004 and 2016 presidential elections, white voters who don’t have a four-year college degree swung to the right across the country, while white voters with a college degree swung to the left. For a state like Kansas, ranked by the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey as the 16th most college-educated state in the country, trends like these would seem to suggest it has the potential to become a swing state. Although popular stereotypes paint a picture of a sparsely-populated rural state, increased urbanization in recent decades has led to the growth of major suburbs and dense cities such as Wichita and the Kansas City metro.

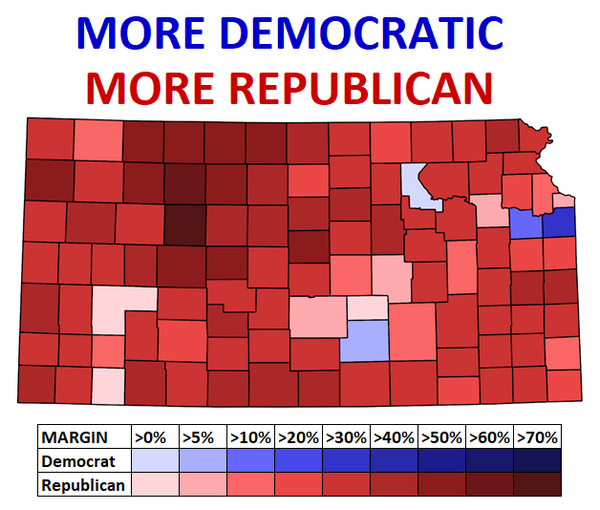

Despite its red lean in presidential races, Kansans have been open to voting for Democratic governors. Both the 2002 and 2018 cycles saw open-seat contests where Democratic candidates won hotly-contested races. In 2002, then-state Insurance Commissioner Kathleen Sebelius (D) won the gubernatorial race 53%-45%. Sixteen years later, voters elevated state Sen. Laura Kelly (D) to the governorship, 48%-43%. Despite the similar margins in both the 2002 and 2018 gubernatorial elections, all but four counties swung right during that time period, as Democratic support urbanized: Johnson County, in the Kansas City suburbs; Riley County, home to Kansas State University; Douglas County, home to the city of Lawrence and the University of Kansas; and Sedgwick County, home to Wichita. (Map 1)

Map 1: Change in Kansas gubernatorial races, 2002-2018

Going back further, some demographic changes may inform that swing.

In 1950, Johnson County was home to just 60,000 residents; today it has grown to more than 600,000 and is the most populous county in the state. It hasn’t reported less than 10% decennial growth in the census since 1920, and has a median income of more than $80,000. Unfortunately for Republicans, it is only getting bluer, as it switched from voting for Mitt Romney by 17 percentage points in 2012 to voting for Donald Trump by just three points in 2016. Given these trends, it wouldn’t be surprising if the county supports presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden in the fall.

Still, just as the Republican Party is losing college-educated voters overall, it is gaining non-college educated ones — and for a state where 20% of residents live in Johnson County, and an additional 24% live in the other three counties noted above as shifting toward the Democrats recently, that’s an important distinction. Although the state did trend leftwards between 2012 and 2016 — moving from 26 points to the right of the national vote to slightly less than 22 points more rightward — the state remains solidly red, and the Crystal Ball rates it as Safe Republican in the Electoral College.

A 2018 glimmer — with a 2020 chance as well?

In the early 2000s, Kansas was a red state, but one where Democrats held some key offices. In 1998, Democrats captured the red-leaning 3rd District with Blue Dog Dennis Moore (D, KS-3). As it does today, KS-3 included all of Johnson County — a reliable GOP bastion, at the time. With the election of Kathleen Sebelius in the 2002 gubernatorial race, the Kansas Democratic Party could claim to be a credible political organization, capable of both regular wins and off-year pickups such as the election of Nancy Boyda (D) in the even further red-leaning KS-2. In 2010, though, the Republican wave that swept across the country also rolled across the Kansas plains. The GOP picked up the governorship with then-Sen. Sam Brownback (R-KS), after Sebelius — who would have been term-limited anyway — joined the Obama administration. Despite a string of close races early in his career, Moore had begun to lock down his district by 2004. When he retired in 2010, though, the district reverted into GOP hands. By 2011, Republicans controlled every facet of Kansas state government. In 2014, Republicans, despite Brownback’s sagging approvals and legislative infighting, retained their hold on all statewide and federal offices.

In 2018, however, the Kansas Democratic Party at last saw some revitalization. In the state House, Democrats picked up a dozen seats, especially in more urban parts of eastern Kansas, and came within one seat of breaking the Republican supermajority. Furthermore, Democrats also flipped KS-3 in a landslide: first-time candidate Sharice Davids (D) defeated incumbent GOP Rep. Kevin Yoder by nearly 10 percentage points. Of course, Democrats’ sweetest victory that year came in the gubernatorial race, as now-Gov. Laura Kelly defeated Kris Kobach — at the time, the sitting Secretary of State with a knack for generating controversy — by five percentage points, a decisive margin for this red state.

Looking ahead to Aug. 4, Kobach is running in this year’s Senate primary. The Crystal Ball rates the race as Likely Republican, though if Kobach wins the primary, a more competitive rating may be considered. Until then, Kansas Democrats look with anticipation on one of their first real chances to pick up a Senate seat in the state, which hasn’t sent a Democratic senator to Congress since the 1932 election. Let’s look at the three leading contenders:

Kris Kobach

Known for his hardline stances on some wedge issues, Kobach, an Ivy League-educated lawyer, has allied with organizations such as FAIR (Federation for American Immigration Reform) to curtail immigration, going into the courts on multiple occasions to block illegal immigrants from receiving tuition and to support tough immigration laws, like Arizona’s SB 1070. As an unsuccessful congressional candidate in 2004, he called for the US military to be sent to the Mexican border, and for the replacement of the federal income tax with a national sales tax. Initially elected as Secretary of State in 2010, his two terms were marked with controversy: he labeled the League of Women’s Voters a “communist” group and proposed tough new voter ID laws that critics called discriminatory. In the 2018 gubernatorial race, Kobach’s baggage, combined with Brownback’s poor image in the state, proved too much for voters.

Roger Marshall

Rep. Roger Marshall (R, KS-1) represents Kansas’s “Big First” district, which spans much of the state’s geographic area. KS-1 has served as a springboard for some of the state’s most prominent figures: both Kansas’ current senators represented it in the House before making the move up, and former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole (R-KS) is from the district. Marshall hails from the party’s establishment wing and was elected by defeating the more bombastic Rep. Tim Huelskamp in the 2016 primary — Huelskamp was a vocal member of the conservative Freedom Caucus, and was known for agitating the GOP leadership. For Marshall, deserting his secure House seat was quite a gamble, and he remains the underdog to Kobach in the primary.

One of the biggest factors sustaining Marshall’s campaign is the *lack* of another candidate: Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) made repeated appeals to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to enter the race. Pompeo, who has a strong rapport with the president and local roots (before serving in the administration, he represented the Wichita-based KS-4), would have been a strong candidate. However, Pompeo seems uninterested in returning to the legislative branch, and the filing deadline, June 1, has passed. Days before the filing deadline, Marshall got a break when state Senate President Susan Wagle, another serious candidate, ended her campaign. As such, Marshall seems the most palatable option to Republicans who are wary of Kobach, although former Kansas City Chiefs player and businessman Dave Lindstrom could be a wild card, and wealthy businessman Bob Hamilton, who has spent heavily on television advertisements, could also draw away from Marshall’s base. Even while Pompeo’s potential candidacy was looming, Marshall garnered some endorsements from establishment elements in his party — Bob Dole, for instance, endorsed him in January.

Barbara Bollier

State Sen. Barbara Bollier (D), who switched parties in 2018, is the almost certain Democratic nominee for the Senate race; she has support from national groups such as EMILY’s List and the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. Originally a Republican, she accumulated a fairly liberal voting record — she opposed Gov. Brownback’s signature tax cuts, supports Medicaid expansion, and is pro-choice on abortion — so she fits in well across the aisle. All things considered, she’s a formidable candidate who has fundraised well. Still, some wonder whether a more conservative candidate — such as former state House Minority Leader Paul Davis (D), who lost close races for governor in 2014 and for Kansas’s 2nd Congressional District in 2018 — could have been a stronger opponent.

Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas (City) anymore

Much of the Kansas Democratic Party’s strategy in backing Bollier has been to focus on selecting a candidate who can appeal to voters in places like Johnson County and other affluent suburbs — in an attempt to replicate the Kelly 2018 map against, potentially, the same opponent. But if that is their goal, that may very well be a mistake; it was rural voters, not suburban ones, that actually did the most to tank Kobach’s campaign for governor.

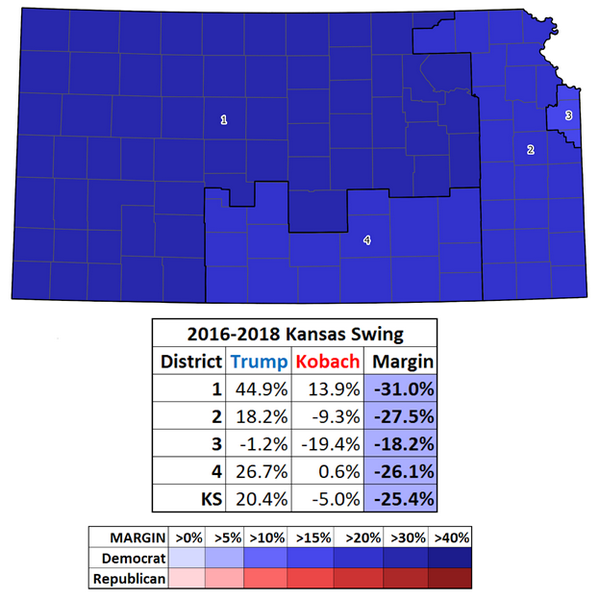

Kobach underperformed President Trump in each of Kansas’s four congressional districts, but his greatest underperformance was actually in the Big First, where he trailed the president by 31 points — in a district that favored Trump by a three-to-one margin over Hillary Clinton, Kobach earned a bare-majority 51% share of the vote. By contrast, Bollier has relatively limited room for improvement in the suburban 3rd District, given that Kobach “only” did 18 points worse than Trump, as Map 2 shows.

Map 2: Kobach’s underperformance vs Trump

Perhaps the national Democrats are on the right track. After all, it would be logical to assume that a stronger suburban performance could override a weaker rural one — this has been the tradeoff that Democrats have made in recent years, and it has generally seemed to work, especially in 2018. But with television advertising that already seems to be focusing on the (admittedly more densely populated) eastern part of the state, this could be an unrecognized error, especially considering turnout differentials.

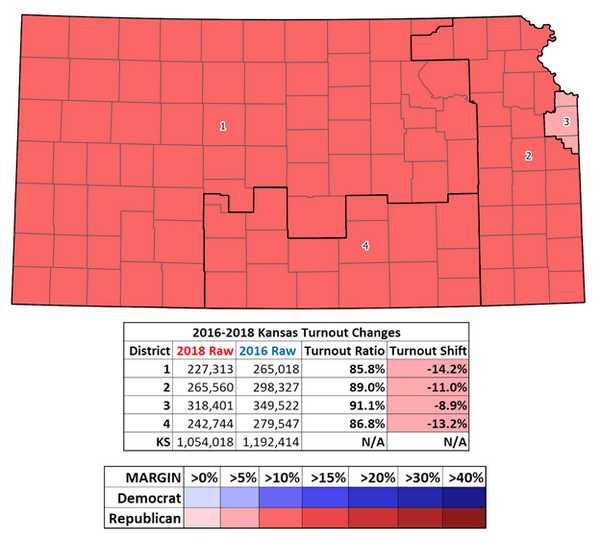

Voter Turnout Shifts, 2016-2018

It’s a well-known phenomenon that voter turnout usually falls in midterms. In the 2010 and 2014 midterms, when Barack Obama was president and higher electoral enthusiasm tended to reside in the Republican corner, this resulted in increased relative turnout for Republican voters. In 2018, however, this trend was seemingly reversed, on both a national scale and in Kansas. Of the state’s four congressional districts, the three represented by Republicans (the 1st, 2nd, and 4th) all saw larger turnout decreases compared to the Democratic-won KS-3. In the 3rd District, turnout remained at 91.1% of 2016 levels vis-a-vis an average of 87.2% in Republican districts (Map 3).

Map 3: Kansas turnout change, 2016 – 2018

There are no simple answers here, but regardless, it seems readily apparent that Kansas will be a race to watch for prognosticators and laymen alike in 2020, and beyond.

| Jacob P. Hornstein is an election analyst and political observer from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His twitter handle is @ChapelHill_R. |