| Dear Readers: Tomorrow (Friday, Feb. 21), the University of Virginia Center for Politics will be hosting a conversation between former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Center for Politics Director Larry J. Sabato on the Grounds of UVA from 12:30 p.m. to 2 p.m. While registration for the event is full, we will be livestreaming it at https://livestream.com/tavco/PaulRyan. |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Bernie Sanders may be a poorer fit for the Democrats’ Senate targets than some other Democratic contenders if he wins the nomination.

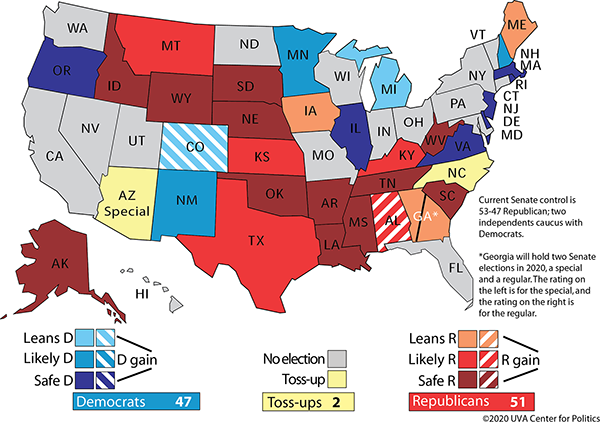

— There are two Senate rating changes this week: Colorado moves from Toss-up to Leans Democratic, while Alabama moves from Leans Republican to Likely Republican.

— Republicans remain favored to hold the majority.

Table 1: Crystal Ball Senate rating changes

Sanders, the Senate, and the Sun Belt

Bernie Sanders’ ascendancy to a soft frontrunning position in the still-uncertain Democratic presidential primary has led many to wonder not just about his general election odds against Donald Trump, but also whether he would be a good “running mate” for Democrats in the most important Senate races.

Generally speaking, Sanders’ national polling in horse race matchups against Donald Trump is similar to that of Joe Biden, himself a soft frontrunner before the voting started, and Michael Bloomberg, who is trying to position himself as a less liberal alternative to Sanders. As of Wednesday afternoon, Biden, Bloomberg, and Sanders all led Trump by a little under five points nationally according to the aggregated RealClearPolitics average, although individual pollsters often show more variation than that. Still, the national polls right now tell a more consistent story than the ones released four years ago at this time, when Hillary Clinton led Donald Trump by three points nationally while Marco Rubio led Clinton by five and Ted Cruz led her by a point. Obviously, Trump overcame his weaker position at this point of the 2016 cycle to win the Electoral College anyway.

A recent report by the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group found that both Biden and Sanders lead Trump nationally, but that the makeup of their support is a little bit different. Sanders does better with younger and less affluent voters, while Biden does better with older and more affluent ones. Biden also performs better with white voters — two points better among whites without a college degree and eight points better among whites with a four-year degree. The latter group’s voting power is evident in some of the Sun Belt places where Hillary Clinton performed markedly better in 2016 than Barack Obama did in 2012: places like metro Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Houston, Phoenix, and Raleigh. All of these big urban areas are in states (Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas) that host Senate races this year, with Arizona and North Carolina standing out as our only two states rated as Toss-ups. For now, Sanders appears to be weaker though still competitive in these states. This is part of the reason why some Democratic leaders worry about a potential Sanders nomination, because they fear he would cede some recent Democratic gains in well-off suburban areas due to his strongly progressive/liberal policy proposals.

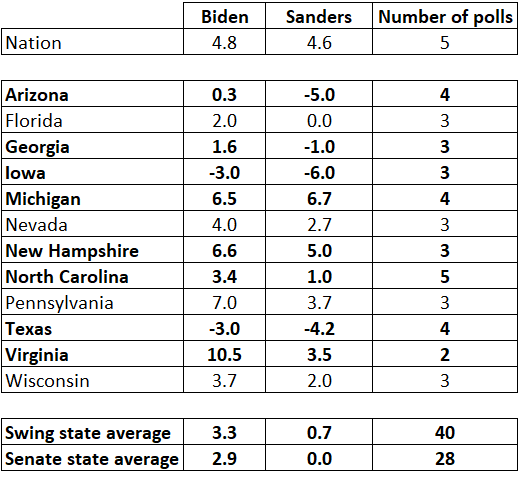

This shows up in state-by-state polling, too. A few weeks ago in the Crystal Ball, Alan Abramowitz showed how Sanders was doing a bit worse in the key states than Biden. Table 2 updates Abramowitz’s compilation of numbers from the RealClearPolitics national and state polling averages, with the states featuring Senate races in bold. Note that one of the biggest discrepancies between Biden and Sanders comes in Arizona, a state that, according to our ratings, features Toss-up races for president and Senate, and probably is a must-win for Democrats to capture a Senate majority, if not the Electoral College.

Table 2: Biden and Sanders vs. Trump in RCP polling average

Note: States in bold also have a Senate race this year (or two Senate races, in the case of Georgia).

Source: RealClearPolitics as of the afternoon of Wednesday, Feb. 19.

One major note about Table 2: These state-level averages include polls that are, at this point, several months old, whereas the national polling is fresher. Also, some key Senate and/or presidential states are not included because of a lack of polling.

There will be plenty of time to assess the impact of the Democratic nominee on the Senate picture — especially once we know with more confidence who that person is going to be. But the numbers illustrate why Democrats involved in Senate races may prefer other candidates to Sanders.

Alabama and Colorado rating changes

In the meantime, we have two rating changes, both of which highlight each party’s best pickup opportunities this year.

A roadblock to Democrats’ hopes of winning control of the U.S. Senate is the reality that even though they are only defending 12 seats on this year’s map to the Republicans’ 23, the most vulnerable seat on the map is one of those they currently hold: that of Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL). In other words, even though the Republicans are playing much more defense than the Democrats are, they have the easiest pickup.

Jones, a fluke special election winner in 2017, appears likely to face former Sen. Jeff Sessions, former Auburn University football coach Tommy Tuberville, or Rep. Bradley Byrne (R, AL-1) in the general election (two of them seem likely to advance to a runoff following the March 3 primary, with Sessions the best bet to grab one of those spots). That is a blow to Jones, who surely hoped to face disastrous 2017 opponent Roy Moore. Moore is running again but is clearly lagging behind the other candidates, to the point where it would be a huge surprise if he made a runoff.

Jones’ vote to remove the president in the impeachment trial will make it even harder for him to create the kind of electoral distance he’ll need from the Democratic presidential nominee to win reelection. We are just having a harder and harder time seeing much of a glimmer of hope for Jones, who according to a recent Alabama Daily News/Mason-Dixon poll is lagging the three leading Republicans by margins ranging from eight to 13 points. Jones benefited from a disproportionately strong Democratic turnout in the 2017 special election — helpfully illustrated by political mapper Matt Isbell — that is highly unlikely to be repeated in a presidential year.

We are moving Alabama’s Senate race from Leans Republican to Likely Republican.

The likely loss of Alabama means that Democrats have to win at least four currently Republican-held seats to get to a 50-50 tie in the Senate, and five for an outright majority. Colorado has long stood out as the Democrats’ best target, and we’re formalizing that in our ratings by moving Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) from Toss-up to Leans Democratic.

While polling has been sparse in Colorado, Gardner has long appeared endangered by the Centennial State’s shift toward the Democrats. He has emphasized some local issues but has generally stuck with the president on the bigger-picture ones that are increasingly more salient in our nationalized elections. Gardner is in a tough spot: After distancing himself from Trump in 2016, Gardner risks losing his own base voters if he criticizes Trump, but if Trump again loses the state, voters may not have much reason to split their tickets in Gardner’s favor. He faces a version of the same dilemma that Jones does in Alabama, although Jones is in a significantly worse position because Alabama is an overwhelmingly Republican state, whereas Colorado is just a light shade of blue.

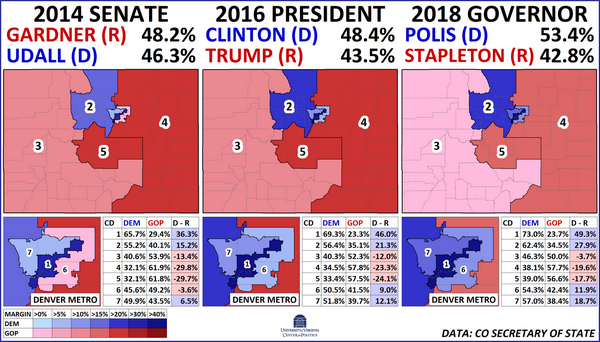

That said, the trendlines in Colorado must be worrying to Gardner.

Breaking recent Colorado elections down by congressional district, Gardner’s unusual strength in 2014 is apparent (Map 1). Specifically, his strength in the 6th Congressional District was significant. This suburban seat is situated in the eastern Denver metro area, taking in populous communities like Aurora and Centennial. The current iteration of CO-6 has existed since 2012 and, in statewide elections, has typically picked the winners — despite Gardner’s success there in 2014, then-Gov. John Hickenlooper (D) carried it as part of his successful reelection effort that year.

Map 1: Recent Colorado races by congressional district

In 2014, Gardner won his Senate seat by a 48%-46% spread over then-Sen. Mark Udall (D-CO), but had a larger 3.6% advantage in the 6th district — in other words, CO-6 voted almost two percentage points more Republican than the state.

Two years later, Hillary Clinton would carry the Centennial State’s electoral votes by a 5% margin, but she fared even better with the suburbanites in CO-6, winning it by nine percentage points. In fact, between those 2014 and 2016 contests, CO-6 swung nearly 13 percentage points from Udall to Clinton — no other district in the state saw a double-digit blue shift. Perhaps more notably, in 2016, CO-6 leaned four points more Democratic than the state as a whole.

In Colorado, 2018 looked much more like a solidification of 2016 than a repeat of 2014. In contrast to Hickenlooper’s closely-fought gubernatorial race in 2014, then-Rep. Jared Polis (D, CO-2) seemed to be in the driver’s seat for much of the campaign. He ultimately defeated then-state Treasurer Walker Stapleton (R) by a 10.6% spread. CO-6 retained its blue lean, going to Polis by a dozen points in a 54%-42% vote.

If Gardner were to cobble together a winning coalition, it seems possible that he’d do so without carrying CO-6, especially given its present blue lean. Indeed, his 2014 coalition would offer some precedent to this. At the time, his victory was notable because he won without Jefferson County, long considered a reliable bellwether county in state races. Though Jefferson County sits on the other side of the Denver area, it’s demographically comparable to CO-6.

The 6th District saw considerable crossover voting in 2016, but it seems unlikely that Democratic voters will defect to Gardner in the Senate race, at least not in the necessary volume he’d traditionally need. That year, Rep. Mike Coffman (R, CO-6), a perpetually elusive target on national Democrats’ wish list, won reelection by a 51%-43% margin by carrying 170 precincts that supported Clinton. Democrats finally defeated Coffman in 2018 by a 54%-43% spread. The 2018 congressional result closely mirrored Polis’ showing there in the gubernatorial contest and suggested that voters were making few distinctions between candidates and their respective parties.

The likely Democratic nominee, Hickenlooper, is not a perfect candidate, but he is a proven one, having won the state’s governorship in the difficult Democratic years of 2010 and 2014. He is hardly a favorite of the left, but that’s probably an asset in a general election environment. Republicans have been trying to criticize Hickenlooper over whether it was appropriate for him to accept free air travel while he was governor. Gardner’s path to victory likely involves Trump getting at least a little bit closer in Colorado than he did in 2016 and outwitting Hickenlooper on the trail. This reelection path for Gardner isn’t impossible, but he needs some things to break his way in order to retain his seat. Hence, it makes more sense to look at Gardner as an underdog.

Today’s two ratings shifts help clarify the lowest-hanging fruit for both Republicans and Democrats this November: Both parties are now outright favorites to each flip one of the other party’s seats, but the GOP has a firmer grip on Alabama than Democrats do on Colorado. If these were the only flips this year, Republicans would obviously be pleased, because that would mean that they would retain their 53-47 majority.

In order to make gains, Democrats will have to flip more seats. Based on our ratings, their next two best opportunities are in Arizona and North Carolina, both Toss-ups. The November matchup is effectively set in Arizona, with appointed Sen. Martha McSally (R) slated to face former astronaut Mark Kelly (D). While McSally’s fundraising has been good, Kelly’s has been extraordinary. The Senate race may track with the presidential, although it’s not hard to imagine Kelly being able to potentially do better than the Democratic presidential nominee. However, if Arizona ends up breaking to Trump, McSally could very well have the advantage. She is embracing the president, and she may be wise to do so if Trump wins the state again and especially if he exceeds his 2016 margin (3.5 points).

Meanwhile, national Democrats hope that former state Sen. Cal Cunningham (D) advances past the primary to face Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC), but poorly-funded state Sen. Erica Smith (D) appears to be getting some late help from a mysterious, probably Republican outside group that hopes she can win the primary. This kind of primary meddling has become more common in recent years, with the most famous example being now-former Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-MO) helping then-Rep. Todd Akin (R) become her opponent in 2012, and then watching Akin self-destruct in the general election. Tillis would become a favorite again, in our view, if Cunningham loses the primary.

If we had to pick these Toss-ups today, we’d probably give Kelly the edge in Arizona and Tillis the advantage in North Carolina. If that’s indeed what happens, and every other race goes the way of our current ratings, the Senate would be 52-48 Republican, or a Democratic net gain of one. That math helps explain why the Republicans retain a leg up in the battle for the majority, although the Democrats have other targets — most notably in Iowa and Maine — that may eventually slide into the Toss-up category, which could have the effect of making Senate control overall a jump ball.

According to a recent poll from Colby College, Maine already may be a true Toss-up, as that survey had Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) effectively tied in the low 40s with state House Speaker Sara Gideon, her likeliest Democratic opponent. However, based on what we have heard about the race, Collins may be better-positioned than that, and we continue to give her something of the benefit of the doubt even though she’s unquestionably in her most vulnerable position since she entered the Senate in 1997.

Map 2 shows the current state of the Senate based on our ratings.

Map 2: Crystal Ball Senate ratings