KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Unlike in 2016, Bernie Sanders has a real chance to win the Democratic presidential nomination.

— However, he likely will have to broaden his base of support to do so.

— Namely, better showings in big urban and suburban areas are important, particularly as the field narrows.

Sanders 2016: A look back

Bernie Sanders begins his second bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in possession of something he never attained in 2016: A competitive chance of winning.

Sanders’ first try four years ago was respectable. Facing a top-heavy favorite in Hillary Rodham Clinton, he won 22 states — 12 caucuses and 10 primaries, among them the battleground states of Michigan and Wisconsin. He drew 43% of the nationwide Democratic primary vote, which represented more than 13 million voters. As a result, he posted the highest primary vote total in the nation’s history for any candidate not named Obama, Clinton, or Trump.

Yet in 2016, Sanders never had a realistic chance of winning the party’s nomination. Two basic stumbling blocks stood in his way: superdelegates and the South. The former, which comprised 15% of the convention delegates, went virtually en masse for Clinton, as she was a part of the Democratic establishment in a way that Sanders never was or could be. And with Clinton’s firm grip on the minority vote, the Vermont senator was never able to penetrate the South. He lost 12 of 13 primaries across the region (all save Oklahoma), polling barely one third of its aggregate primary vote in the process.

Sanders’ problem garnering the votes of African Americans and Hispanics extended to other regions of the country as well, helping Clinton to dominate the vote in many of the nation’s leading urban centers and their suburbs. The result: In the 10 states with 15 or more electoral votes, Sanders could carry the primary in only one, and that, Michigan, was by less than 20,000 votes out of 1.2 million cast.

Basically, the heart of Sanders’ coalition in 2016 was academic centers and a significant swath of rural America. The latter was an unlikely source of votes for a self-described “democratic socialist.” Antipathy to Clinton was no doubt a major reason for his strong rural vote. So were his full-voiced attacks on what he saw as an insensitive political and economic elite. And in spite of his New York accent, his base in rural Vermont gave him a connection to primary voters in smaller states that Clinton could not match.

Of the 10 primaries that Sanders won, there were three types: those with a progressive pedigree (such as Oregon, Vermont, and Wisconsin); those that were New England neighbors of Vermont (New Hampshire and Rhode Island); and a mixed band of others (from Michigan and Montana to the unlikely trio of Indiana, Oklahoma, and West Virginia). Sanders also had close losses of two percentage points or less in the Iowa caucuses and primaries in Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Missouri, and South Dakota. He ran particularly well in states where independents were allowed to vote in the Democratic primary.

Sanders’ strength in rural areas was evident in the number of counties he carried in a variety of primary states outside the South. In Wisconsin, he won 71 of 72, losing only Milwaukee County to Clinton. In Oregon, he swept 35 of 36, losing only one small county to Clinton by a vote of 101 to 100. In Oklahoma, Sanders carried 75 of 77 counties. And in Michigan, he took all but 10 of the state’s 83 counties.

His victory in the Wolverine State was a microcosm of his strengths and weaknesses in 2016. Clinton dominated the Detroit metro area, winning Wayne County, which includes the city of Detroit, by 60,000 votes. She also carried the city’s two major suburban counties, Oakland and Macomb, the latter the fabled home of blue-collar “Reagan Democrats.” Outside the Detroit area, Clinton picked off Genesee County, which includes Flint, an industrial outpost that is the birthplace of filmmaker and progressive activist Michael Moore (a Sanders backer). But Sanders swept most everywhere else in Michigan, including the county of Washtenaw, which includes the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and nearby Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti.

To be sure, the 2020 Democratic nominating race has a different complexion to it than that of four years ago. Then, Sanders was engaged in a one-on-one fight with Clinton where he needed a majority of the vote in primary and caucus states to prevail.

This time, that will not be the case, at least in the early voting. Pluralities will do, as the Democrats have a far wider field of candidates, including two billionaires in Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer, whose wealth gives them staying power. At this point, it would be no surprise if the wide field of Democratic candidates persisted well into the glut of March primaries. Sanders’ ardent group of supporters, augmented by his ability to raise impressive sums of money, should keep him as a major player in the Democratic race provided he does not unexpectedly tank in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Still, to win the Democratic nomination in 2020, Sanders will ultimately need to be more than the Democratic champion of academe and the rural countryside. Maybe not at the start, but eventually, he will need to show broader vote-getting ability than he did in 2016. That includes breakthroughs in the cities and the suburbs, both critical to Democratic success in the general election, and blue-collar jurisdictions with an industrial heritage such as Flint.

This year’s Democratic race could be profoundly affected by rules changes instituted by the party for 2020. Probably the most significant redefines the controversial role of superdelegates, which are party and elected officials given automatic delegate status by virtue of their position. Superdelegates are free to vote for the candidate of their choice regardless of the result of their state’s primary or caucus.

In 2016, they were crucial to the nomination of Clinton: She would have won without them, but their backing reinforced her edge. This time they will have no vote at all on the first ballot unless there is already a clear-cut winner going into the convention. It is a change that should work to Sanders’ advantage.

But another rules change may not. It encourages states to select their delegates through higher turnout primaries rather than comparatively low turnout caucuses. The latter are a venue that rewards passion, and Sanders’ enthusiastic supporters gave him victories in 12 of the 14 caucus states in 2016, often by lopsided margins. Iowa and Nevada will hold caucuses in 2020, but there will be few other states using the caucus process.

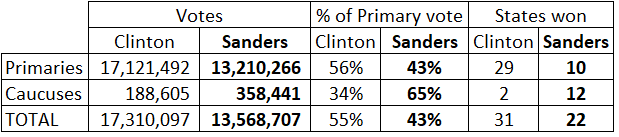

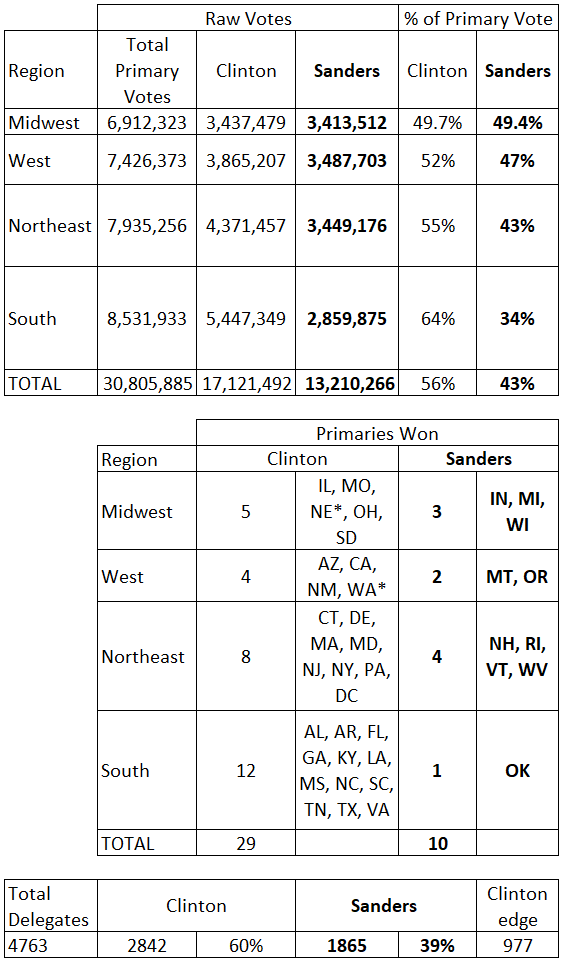

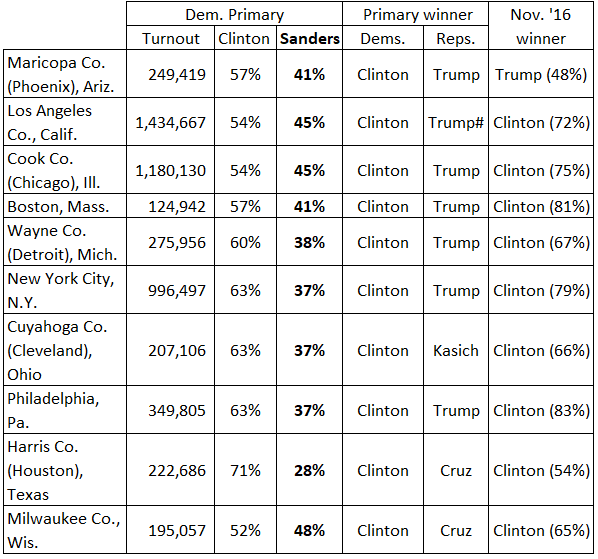

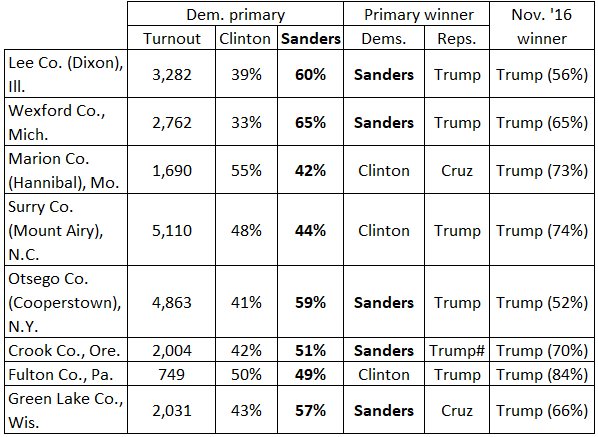

What follows is an in-depth examination of Sanders’ 2016 performance. Table 1 shows the difference in Sanders’ showing in caucuses versus primaries; Table 2 shows the primary vote by region; and Table 3 analyzes a series of sample counties, illustrating Sanders’ strengths and weaknesses in different kinds of places across the country.

Table 1: Sanders dominated in caucuses, Clinton in primaries

| In his first try for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016, Bernie Sanders dominated in the low-turnout world of the caucuses, where his passionate cadre of supporters almost always carried the day. It was more difficult for Sanders, though, in the higher turnout primary states. There, Hillary Rodham Clinton prevailed in most contests, with particular success in states with a high minority population. Unfortunately for Sanders, there were far more primaries than caucuses, and there will be even fewer caucuses in this year’s nomination fight. |

Note: The total number of states won by Sanders and Clinton totals 53, because the District of Columbia primary is included as are both caucuses and non-binding primaries in Nebraska and Washington. In the latter two, Sanders won the caucuses while Clinton took the non-binding primaries. A tally of actual caucus votes was taken in only eight of the 14 states that held them. In the other six caucus states, other measurements of candidate support were used.

Sources: America Votes 32 (CQ Press, an imprint of SAGE) for 2016 Democratic primary results; CNN The Republican and Democratic National Conventions Research & Editorial Guide 2016 (Robert Yoon, editor) for 2016 Democratic caucus results.

Table 2: Regional breakdown of the 2016 Democratic primary and delegate count

| When the presidential roll call was taken at the 2016 Democratic national convention, Bernie Sanders finished nearly 1,000 delegates short of Hillary Rodham Clinton. Much of his deficit was due to his failure to do better among superdelegates and Democratic primary voters in the South. Of the 13 Southern primaries, Sanders carried only one (Oklahoma). And in more than half the other primaries across the region, he was beaten by margins in excess of 2 to 1. As for the superdelegates, Clinton had a lead in the vicinity of 500 among them. |

Note: The delegate count is based on the presidential roll call at the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. An asterisk (*) that accompanies Nebraska and Washington indicates that the states held a non-binding Democratic primary, with delegates selected in a separate caucus process. The District of Columbia is included in the list of Democratic primaries.

Source: America Votes 32 (CQ Press, an imprint of SAGE), 54-55, for the 2016 Democratic primary vote. The delegate tally is based on the 2016 Democratic convention presidential roll call and was compiled by the author, with assistance from the Frontloading HQ website and Robert Yoon of CNN.

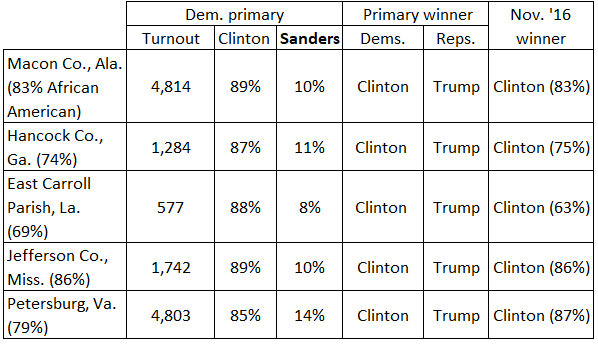

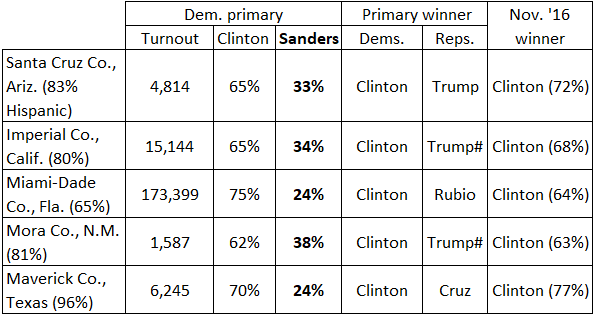

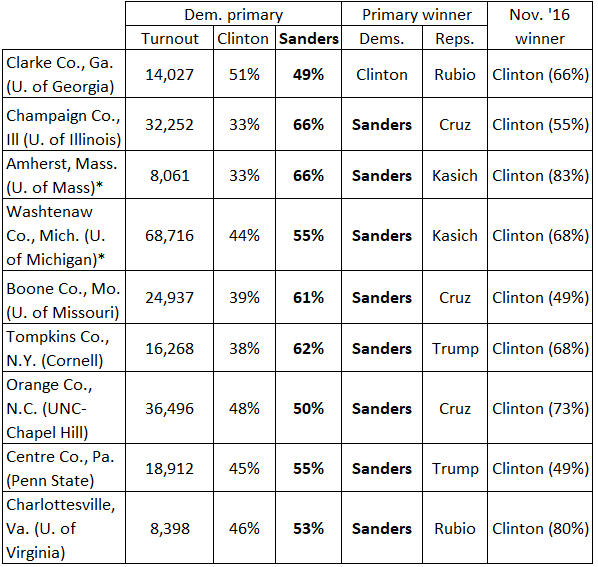

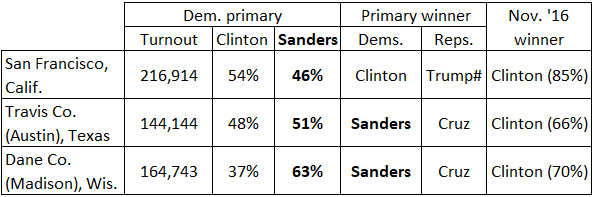

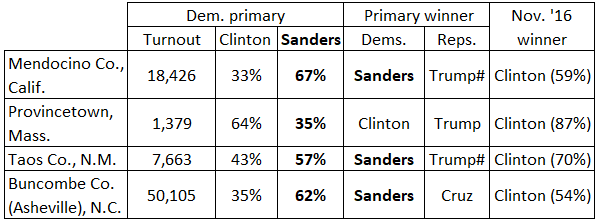

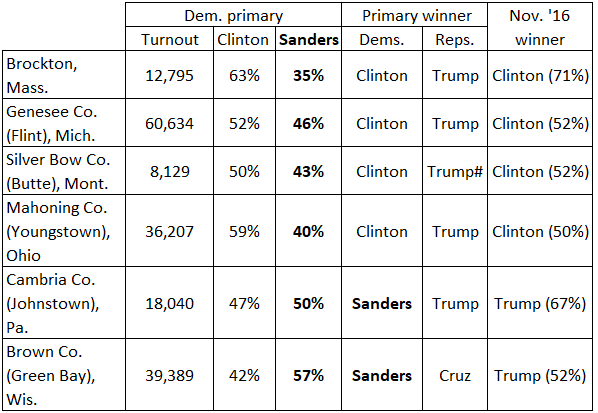

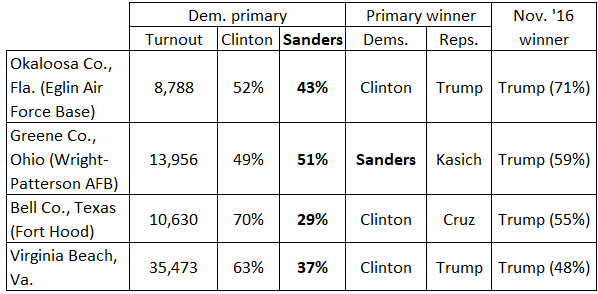

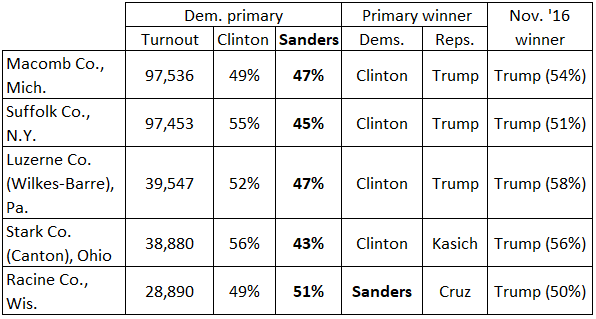

Table 3: 2016 Democratic primary results: A sampling of counties

| The following categories of sample counties seek to show Bernie Sanders’ strengths and weaknesses as a vote-getter in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries. Columns are included that also feature the winner of the Republican primary in each county that is listed, as well as the November 2016 general election winner and their percentage. Wherever candidate percentages appear, they are based on the total vote. A pound sign (#) is used to indicate counties in states where primaries were held after Donald Trump’s last rivals had left the Republican race in early May 2016. All results are based on official primary and general election returns posted on state election web sites. |

TYPES OF COMMUNITIES

At its most elemental level, the nation can be divided into three separate types of communities: urban, suburban, and rural. The largest cities are the cornerstone of the Democratic vote. Rural and small-town America are decidedly Republican. The suburbs are often up for grabs and swing between one party and the other, frequently deciding elections in the process. In the 2016 Democratic primaries, Clinton dominated major urban centers with their large minority populations, and tended to have the upper hand in suburban counties as well. As for Sanders, he swept many rural counties, especially outside the South.

Major urban centers

Major suburban counties

Rural and small-town America

RACIAL COMPOSITION

Minorities, especially African Americans, are arguably the most loyal element of the Democratic coalition. And counties with a sizable African-American population consistently gave Clinton her highest proportion of the Democratic primary and general election vote in 2016. The counties with the highest percentage of African Americans can generally be found in the South; those with the highest proportion of Hispanics in Florida and the Southwest. The minority percentages listed below are based on the 2010 census.

African-American majority

Hispanic majority

LIBERAL BASTIONS

One of the biggest surprises from the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries, at least in this corner, was that Bernie Sanders did not carry San Francisco. Yet he did dominate in other liberal strongholds, especially academic communities. An asterisk (*) indicates that the county or town is the home of multiple colleges. Amherst, Mass., is the site of three colleges: the University of Massachusetts, Amherst College, and Hampshire College. Washtenaw Co., Mich., is the home of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Eastern Michigan University in neighboring Ypsilanti.

College towns

Urban centers

Artistic communities

MORE CONSERVATIVE VENUES

It was not so long ago that labor unions were strong and Democrats were champions of the working class. But in 2016, Donald Trump penetrated deeply into the blue-collar vote, which proved to be a major factor in his upset victory over Hillary Rodham Clinton. Democrats hope to be able to effectively compete with Trump for blue-collar support in 2020, but Sanders will have to make a better case than he did the last time that he is the candidate that can do it.

Industrial heritage

Military influence

Obama-to-Trump counties

Conclusion

New rules and a new field of candidates can make for a changing coalition for a second-time candidate such as Sanders. In the 2008 Democratic primaries, for instance, Clinton lost the African-American vote to Barack Obama. In 2016, she dominated it against Sanders. This time, it is Sanders’ turn to see if he can expand his coalition from last time. To put himself on the road to the White House in 2020, he will need to.

| Rhodes Cook was a political reporter for Congressional Quarterly for more than two decades and is a senior columnist at Sabato’s Crystal Ball. |