KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Democrats netted seven House seats in California in 2018, winning 46 of the megastate’s 53 seats.

— The state’s top-two primary election system can provide clues for the fall. With results almost entirely complete, none of the newly-elected Democrats appear to be in serious trouble, although a few are definitely vulnerable.

— A special election in CA-25 in May might provide Republicans with their best opportunity to claw back some of their lost California turf. We’re moving our rating there from Leans Democratic to Toss-up.

— We also are upgrading a couple of the few remaining GOP-held seats in California to Safe Republican.

Table 1: Crystal Ball House rating changes

The GOP tries to regain lost ground in California

Nowhere did the Democrats pick up more seats in 2018 than in California. They netted seven seats as part of their 40-seat net gain in the midterm, which gave them an incredible 46-7 edge statewide.

Democrats now hold 87% of the House seats in California despite winning only about two-thirds of the House vote in 2018. The Democrats clearly dominate California, but their House advantage in the state seems at least a little inflated.

Republicans have not flipped a House seat in California previously held by a Democrat since 1998. That year, California elected a 28-24 Democratic House majority. So over the course of two decades, the Democrats’ edge in the statewide House delegation has ballooned from four to 39.

The Democratic surge in California has come primarily in three elections: 2000, 2012, and 2018.

In 2000, Democrats flipped four seats: One of the victors that year was Adam Schiff (D, CA-28), who as chairman of the House Intelligence Committee has become one of the House’s more visible Democrats.

A dozen years later, Democrats netted four seats, as they benefited from a nonpartisan redistricting system adopted by voters in a 2010 ballot issue (Democrats arguably were able to influence the remap to their own benefit).

Democrats then netted seven additional seats in 2018, aided by a good political climate that got them over the top in some Barack Obama-won districts that had evaded them earlier in the decade (CA-10 and CA-21) while also sweeping a series of changing suburban districts in Southern California that Hillary Clinton carried after Mitt Romney won them four years prior (CA-25, CA-39, CA-45, CA-48, and CA-49).

As they try to figure out a way to win back the U.S. House majority, Republicans surely hope to claw back at least some lost ground in California. At first blush, though, they don’t necessarily have any great targets there.

While Democrats hold 30 districts across the country that Donald Trump carried in 2016 — these are the seats that make the most sense as GOP House targets, particularly if Trump carries them again — there are not any Trump-won districts held by Democrats in California.

So despite the horrible beating Republicans have taken in the Golden State over the course of the decade, there is not a single seat they’ve lost that looks like it will be very easy for them to win back in November.

But they do have some targets, and the primary results give us some clues. Based on history, at least a couple of the seats that the Democrats picked up in 2018 are not really realistic targets for Republicans this year. But a few of the others very well might be.

Clues from the primary

Typically, we wouldn’t use a state’s primary results as some sort of preview of the fall, but California is different because of the voting system it uses.

California uses a top-two primary system in which candidates from all parties compete on the same ballot in the primary, with the top two finishers regardless of party advancing to the general election. This system has been in place since the 2012 election.

We’ve compiled the combined Democratic and Republican voting in all of these districts over the course of the decade, and there are a few general trends we’ve noticed.

This method excludes races where two members of the same party, or a member of a major party and a minor party, advanced to the general election. Our method of counting also excludes all non-major party votes.

The first round, all-party voting does usually provide a decent guide to the fall, although more often than not, the Democrats do better in November than they do in the primary. However, the one year that was more of an exception was 2016 — the year most directly comparable to 2020 because it took place during a presidential primary where only one side had a real contest going on (the Democrats in both years).

On average, the Democratic share of the two-party vote in each district that we included in our compilation went up about six percentage points in 2012 House races, four points in 2014, and a little over three points in 2018, while it went down by about one and a half points in 2016.

We drilled down a little bit deeper to just look at competitive races — those that we rated as something other than Safe Democratic or Safe Republican in our final House ratings for each of the last four cycles. There were 36 over that timeframe; in all but five of those races, the Democratic voteshare increased from the primary to the general. Again, three of the five exceptions came in 2016.

The hope for Republicans is that 2020 looks more like 2016 than the other years. That’s because just modest improvements by Democrats over their party’s 2020 first-round performance would put them over the top in all 46 of the districts they currently hold.

Let’s focus on the most competitive districts over the past few cycles as we interpret the meaning of the primary results.

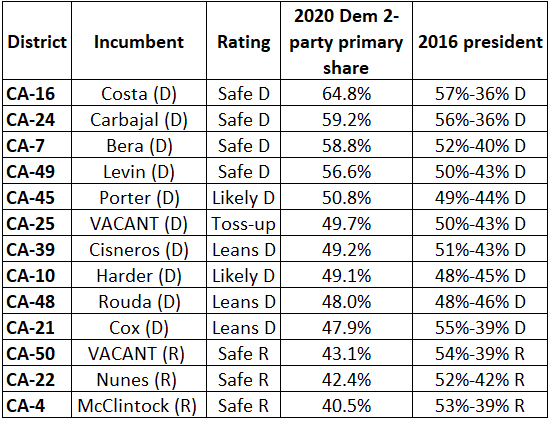

Table 2 shows the first-round two-party primary results for competitive or potentially competitive districts in California; the list includes the seven that the Democrats picked up in 2018 (CA-10, CA-21, CA-25, CA-39, CA-45, CA-48, and CA-49); three GOP-held seats that were competitive in 2018 (CA-4, CA-22, and CA-50); and three other Democratic seats where Republicans have come close to victory on at least one occasion at some point this decade (CA-7, CA-16, and CA-24). These are also the 13 California districts that we rated as something other than Safe in our final 2018 House ratings.

We’re listing them in order from best Democratic two-party performance in the 2020 primary to worst.

Table 2: 2020 two-party primary results in selected California districts

History can act as a guide as to how we might interpret these results.

First of all, the Republicans have never won a district where they won less than 50% of the two-party primary voting. That covers 212 individual House elections across four election cycles.

Meanwhile, Democrats have won 20 individual races while finishing below 50% of the two-party vote in the first round of voting. That includes six of their seven pickups last cycle.

The Democrats finishing well over 50% in CA-7, CA-16, and CA-24 helps confirm that these districts are not really credible Republican targets anymore. We have rated these districts Safe Democratic all cycle and will continue to do so.

We also have rated CA-49 as Safe Democratic all cycle, and Rep. Mike Levin’s (D) strong showing helps confirm that rating.

Rep. Katie Porter (D, CA-45) also got over the 50% hurdle and does not appear to have a strong opponent for the fall; that helps justify our rating in her district of Likely Democratic.

On the Republican side of the ledger, CA-4, CA-22, and CA-50 are all districts that Donald Trump won by 10 points or more in 2016, and while Democrats have in the past won districts where they only got in the low 40s in the first round of voting, there’s not much reason to think any of these districts will flip in 2020. We’re moving Reps. Tom McClintock (R, CA-4) and Devin Nunes (R, CA-22) to Safe Republican, which matches the rating of CA-50. CA-50 is vacant because former Rep. Duncan Hunter (R) resigned after pleading guilty to misusing campaign funds earlier this cycle, but Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) did not call a special election to replace him.

In the four previous California House elections this decade, the highest share of the two-party vote that the Democrats received in the primary in a race they did not go on to win in the fall was 48.5% in the fluky CA-31 election in 2012. That year, two Republicans advanced to the general election thanks to a four-way split in the Democratic vote — this in a district that would give Obama 54% in the 2012 general election. Presumably, the Democrats would have carried the seat in the fall had they had a candidate; as it was, current Rep. Pete Aguilar (D, CA-31) won the district two years later, a rare bright spot for Democrats in their bleak 2014 midterm year.

Based on that 48.5% cutoff point, three other marginal Democratic districts should be in good shape for Democrats: Reps. Josh Harder (D, CA-10) and Gil Cisneros (D, CA-39), and the vacant seat in CA-25 — but there are special circumstances in CA-25 that we’ll get into later.

Harder and Cisneros sit in districts where the total Democratic share of the two-party vote was slightly over 49%. Both of those districts, CA-10 and CA-39, saw the Democratic vote share jump from primary to general in all four of the previous elections this decade, and by at least two points in every instance. So both still appear to be favored for the fall based on historical trends; Harder’s district is more competitive on paper, at least for president, while Cisneros appears to have a stronger challenger: Young Kim, who came within about four points of beating Cisneros in their race in 2018. We are not altering our ratings of Likely Democratic for CA-10 and Leans Democratic for CA-39 at this time.

One caveat on CA-10, which also serves as a way to explain the few votes remaining to be counted in California. There are about 53,000 unprocessed ballots statewide, and more than 9.5 million were cast statewide, so this is a tiny number of remaining ballots. However, nearly a third of those ballots are in Stanislaus County, which makes up the heart of CA-10. So that may be one district where we see a little bit of a change once the results become totally final.

The GOP’s best opportunities

Let’s now focus on the three remaining districts that probably will be the hardest for the Democrats to hold. Democrats may very well hold on to all three, but a variety of factors, including candidate quality, district partisanship, and timing, give Republicans a real opportunity in all three.

Of the 46 Democratic-held House seats, the party’s primary performance was the weakest in CA-21, a Central Valley seat held by Rep. T.J. Cox (D), and CA-48, a coastal Orange County seat held by Rep. Harley Rouda (D). The Democratic share of the two-party vote was about 48% in both.

Unlike in CA-10 and CA-39, the Democratic voteshare in these districts has not always jumped from the primary to the general: In both districts, the Democratic percentage dropped about a couple of points in 2016 from primary to general — and, remember, that may be the most comparable year to this, given that there was an active Democratic presidential primary but not at an active Republican one in 2016. On the flipside, Democrats did not really strongly contest either of these districts in 2016, and they each now feature Democratic incumbents who will be running real campaigns.

Cox’s win in 2018 was one of the bigger surprises anywhere that year, and certainly the primary voting did not provide a preview of the fall: then-Rep. David Valadao (R, CA-21) walloped Cox 63%-37% in the first round before Cox came back to win by a point in the fall.

Based on presidential partisanship, CA-21 should not be particularly competitive: Hillary Clinton won it by about 15 points in 2016. It is one of the poorest districts in the country and has one of the lowest rates of four-year college attainment, less than 10% overall (the national average is around 30%). Roughly three-quarters of its residents are Hispanic. Valadao won easy victories despite the upballot partisanship in 2012, 2014, and 2016 and is running again. Cox, meanwhile, has been dogged by a number of problems related to unpaid back taxes.

Additionally, our use of the combined two-party voting technique may obscure some important details about the CA-21 count, which was 52%-48% Republican overall. There were two additional candidates in the race besides Cox and Valadao: Rocky De La Fuente (R) and his son Ricardo De La Fuente (D); the elder De La Fuente has achieved something of a cult status among hardcore election-watchers for appearing as a gadfly candidate in all sorts of different races across the country, including many presidential primaries. Anyway, the specific vote count was Valadao 49.7%, Cox 38.7%, Ricardo De La Fuente 9.2%, and Rocky De La Fuente 2.4%. In other words, Cox bled considerably more support to his gadfly De La Fuente opponent than Valadao did. That may or may not matter for the fall.

The bottom line here is that Valadao is the stronger candidate, perhaps to a considerable degree, but Cox has district partisanship on his side.

Meanwhile, Republicans argue that CA-48 is the most fundamentally Republican of the districts the Democrats hold in California. Clinton’s victory, two points, was the narrowest she enjoyed in any district she carried, and Republicans like their candidate, Orange County Supervisor Michelle Steel. This was the seat formerly held by ex-Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R, CA-48), whose best days as a candidate were clearly behind him by 2018.

For now, we’re keeping both CA-21 and CA-48 as Leans Democratic. The most important reason is overall presidential partisanship: Both districts voted Democratic for president in 2016 and seem likely to do so in 2020; that may very well be enough for Democrats to hang onto these seats. Sometimes the most straightforward handicap is the right handicap. CA-21 is the one that’s closer to being a Toss-up in our eyes because of Valadao’s proven ability to generate crossover votes.

That brings us to the final district, CA-25. This district is holding a special election in May following the resignation of first-term Rep. Katie Hill (D) last year after explicit photos of her were leaked online and as she faced allegations of inappropriate relationships with staffers.

Crowded primaries on both sides produced the major party nominees that both national parties wanted: state Assemblywoman Christy Smith (D) and former Navy fighter pilot Mike Garcia (R). Garcia had the more competitive path to advancing, as he had to dispatch former Rep. Steve Knight (R), who Hill beat by about nine points in her decisive 2018 victory. National Republicans seemed to prefer Garcia, a fresh face with an attractive biography, over Knight. Guest columnist Niles Francis took a close look at the district right before Super Tuesday.

There were two separate elections for this seat: a regular primary setting up the November contest, and a special primary setting up the May 12 special election.

Democrats won a combined 49.7% of the regular primary vote and 50.6% of the special primary vote (turnout was a little higher in the special, and the roster of candidates slightly different).

If there was no special election, we’d keep the rating as Leans Democratic for the fall, with Democrats already close to the magic 50% number in the lower-turnout primary. CA-25 is another district where the Democratic voteshare consistently increases in the fall, although that does not include 2014 because two Republicans advanced to the general election that year — this district, like others in California, has swung strongly toward the Democrats just over the past few years.

But the special election throws a real wrinkle into the race. Not only will turnout be lower, but because of the public health crisis, it will be an all-mail special election with perhaps limited in-person voting opportunities. If door-to-door campaigning is limited or eliminated, some observers believe Democrats may be hurt more than Republicans as each side tries to get their voters to submit their ballots (every registered voter in the district will be mailed a ballot with a prepaid postage return envelope provided). Both the National Republican Congressional Committee and Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee have begun spending in the race, a sign that it probably will be highly engaged through the special election. This may be one of the first electoral tests of public attitudes in the time of the coronavirus, and the race may eventually attract broader media attention, much like other closely-watched special elections in recent memory (GA-6 in 2017, PA-18 and OH-12 in 2018, and the do-over election in NC-9 last year).

The uncertainty leads us to move the race from Leans Democratic to Toss-up.

If the Democrats hold on, they should be fine in CA-25 in the fall — and perhaps might be anyway even if Garcia wins. But of course there are lots of uncertainties about what impact coronavirus might have in the fall too.

California, with a robust absentee voting apparatus, seems better-equipped than many other states to deal with an election less reliant on in-person voting, if it comes to that.