KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— At long last, the primary season begins tonight in Iowa.

— The calendar is frontloaded, with the heart of the action coming from March 3-17.

— If there is not a clear leader by St. Patrick’s Day, and especially by the end of April, the primary electorate may not actually be able to crown a clear winner.

Our guide to the 2020 Democratic primary

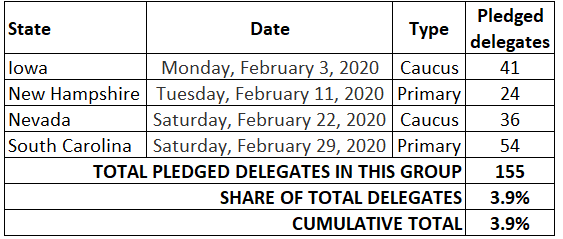

The voting in the Democratic presidential contest is finally upon us. Iowa begins the march to the July Democratic National Convention, followed by New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina in February.

These early contests will get loads of attention throughout the month, although the dirty little secret is that, together, they only account for a pittance of the delegates that will be awarded in the primaries and caucuses. There are 3,979 of them up for grabs in 57 contests, with 1,991 required for a majority.

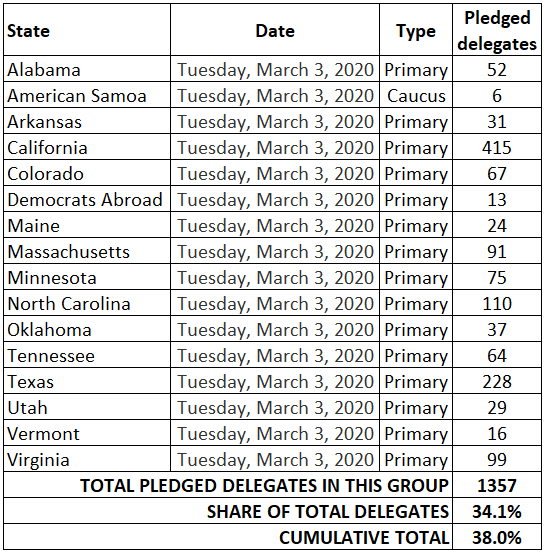

Every year, there is a Super Tuesday, this year on March 3. But it may be more appropriate to look at the March 3-March 17 span as “Super Two-weeks.” A flood of contests bookended by two ethnic holidays — Illinois’ Casimir Pulaski Day (celebrated in honor of a Polish Revolutionary War hero the day before Super Tuesday on March 2) and St. Patrick’s Day on March 17 — may effectively decide the nomination.

Or not.

In some ways, the race has been stable. A year ago on this date, Joe Biden was the clear national polling frontrunner, with Bernie Sanders in second. That is still the case today. At the same time, several candidates who seemed like they could be very formidable contenders for the nomination — such as Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Beto O’Rourke — fizzled. They were surpassed in the pecking order by an unsurprising contender, Elizabeth Warren, and a surprising one, Pete Buttigieg, along with free-spenders Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer. It is remarkable and unusual that the vast majority of all the television ad spending so far has been spent by that latter pair. Other candidates lurk, such as Amy Klobuchar, who is hoping for a late break in Iowa. And lest we anger the #YangGang, Andrew Yang has proven more durable than much better known contenders who are out or barely hanging on.

Biden has been a soft frontrunner this whole time, but no one should be shocked if someone else emerges instead. Sanders has reasserted himself as Biden’s top rival in recent weeks.

It is possible, though not likely, that one candidate will essentially end the race quickly with a lightning strike that convinces the other candidates that they have no real path to the nomination. John Kerry’s victory in 2004 and John McCain’s in 2008 are examples of how this can work: It became clear to campaign observers and participants fairly early in those races that those candidates would be nominated. Even races that remain contested deep into the primary calendar are not always in doubt: Mitt Romney in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016 were well-positioned early on, although their opponents kept fighting into the spring. In the 2008 and 2016 Democratic primary races, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, respectively, had major competition until the end of the primary calendar, although realistically they each had the nomination sewn up months prior.

By the end of the Super Two-weeks, more than 60% of all the delegates will have been awarded. There may be a clear leader at that point who could be effectively impossible to catch given the Democrats’ proportional delegate allocation rules, or no clear leader at that time, making it hard for any candidate to capture a majority of the delegates by the end of the nomination season.

What follows is a guide to the primary schedule, organized chronologically. First of all, remember a couple of ground rules:

— All states award delegates proportionally, with a 15% threshold required to receive delegates at the statewide or sub-statewide level (sub-statewide delegates are typically awarded at the congressional district level, although some states use other methods). Of course, if only one candidate passes that threshold at a certain statewide or sub-statewide level, then that candidate is entitled to all the delegates. For instance, in 2016, Sanders beat Clinton in his home state of Vermont 86%-14%; Clinton fell short of the threshold, so she received no delegates there. The same thing happened to Sanders in, for instance, Mississippi’s Second Congressional District, where Clinton won 87%-12%. A much more crowded field makes the 15% cutoff significantly more challenging to attain than in a two-person race.

— Superdelegates, those delegates who attain their position through holding certain offices and who can support anyone they want at the convention, cannot truly participate in the convention unless it goes to a second ballot, something that hasn’t happened since the 1952 Democratic convention. So they don’t have any bearing on the process — at least for now.

We have broken the race down into eight stages: some are limited to just a single day, while some of them stretch over the course of several weeks.

Whether the outcome of the primary prompts another eight stages — those of grief — will be in the eye of the beholder.

We used several sources for this project: Ballotpedia, Frontloading HQ, the Green Papers, and our friends at Decision Desk HQ, with whom we’ll be tracking delegate counts throughout the primary season.

February: The Sizzle Before the Steak

For all of the attention these contests will generate, the first four carve-out states only have less than 4% of the total pledged delegates. One can understand why Michael Bloomberg can skip them and still believe he has a path to the nomination: The big prizes come later.

Recent polling has suggested Sanders may have an edge in Iowa and, particularly, New Hampshire (but Iowa at least remains very much in flux). He has also been very competitive in Nevada. There exists the possibility that Sanders could sweep the first three contests. Would this erode Biden’s support in South Carolina, the first state with a majority African-American electorate? It’s hard to know.

Buttigieg has been polling well in lily-white Iowa and New Hampshire, but not so much in the other two states, which are much more diverse. While Buttigieg is well-funded, he likely wouldn’t have a real path to the nomination without some sort of major breakthrough in one of the first two states.

If Warren finishes consistently behind Sanders and Buttigieg in the first two states, she might struggle to formulate a real rationale to continue. For Klobuchar, any small chance she has is probably predicated on winning Iowa or otherwise performing a lot better there than poll averages have suggested.

The others need to prove something through actual performances to merit mention, although Tom Steyer has had some decent polling in Nevada and South Carolina.

Super Tuesday, March 3: The National Primary

Note: Democrats Abroad voting begins on Super Tuesday but does not end until March 10.

This is the closest thing we have to a single, national primary. The two biggest states, California and Texas, vote this day, and a little over a third of all the delegates are awarded.

If Sanders has a strong February, as seems possible, this day will test his true strength. Almost every kind of state and demographic group is represented. More than half of the old Confederacy votes on Super Tuesday (six of the 11 classically-defined Southern states), and many of them have large contingents of black voters. Will Biden do well in these states, as Hillary Clinton did four years ago? Or is there more of a muddled result? Depending on how strong Biden is with black voters, and how splintered the vote may become, the 15% delegate thresholds could be hard for non-Biden candidates to attain in certain congressional districts, or even at the statewide level.

Much recent polling has shown Sanders leading with Hispanic voters — perhaps as a result, he has polled competitively in Texas and has often led in California. Can he win these big states, and actually get a substantial delegate edge in them if he does? And then there’s Bloomberg — here is where his well-funded campaign will be put to the test. Sanders’ rise may actually be what Bloomberg wants, because he may be able to pitch himself as the only one who can prevent the independent Vermont senator from winning the nomination if a “Stop Sanders” movement emerges.

One important note: California typically takes weeks to finalize its voting, and the late-counted votes may very well alter the final results considerably (this is true in both primaries and general elections). Part of the reason for this is that California allows mailed ballots to be counted so long as they are postmarked by Election Day — meaning that some ballots actually arrive days after Election Day.

Late-counted votes helped Sanders make up ground in 2016. One initial election night story about the primary noted that Clinton had been leading 62%-37%. By the time the vote was finalized a month later, Clinton’s actual margin was 53%-46%. Needless to say, it’ll take a while for the precise delegate counts to be calculated in California, too. Let’s also remember that, in a conspiracy-minded era, there will be nothing inherently surprising or nefarious about a vote count in California that takes a long time to finalize or that looks substantially different when fully tabulated than it did the morning after the election.

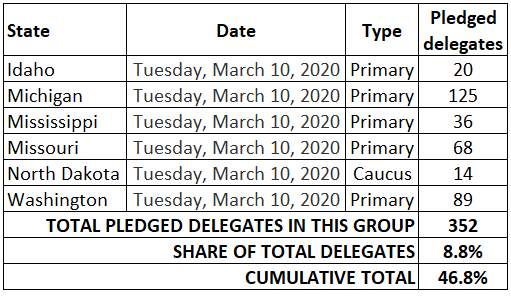

Tuesday, March 10: Northern Exposure

Note: North Dakota is holding a distinct delegate-selection event it is calling a “Firehouse Caucus.”

It’s hard to tie these states together geographically, but the two biggest prizes, Michigan and Washington, are significant northern states that both produced intriguing results in 2016. In the Wolverine State, polls totally missed Sanders’ upset victory, which may have prolonged the race; in the Evergreen State, Sanders easily won a caucus, which awarded delegates, but Clinton won a subsequent beauty contest primary. Washington now will award its delegates via the primary as part of a broader shift away from caucuses in the Democratic race. As Rhodes Cook noted in the Crystal Ball last week, this is a change that could hurt Sanders, because he dominated in caucuses in 2016.

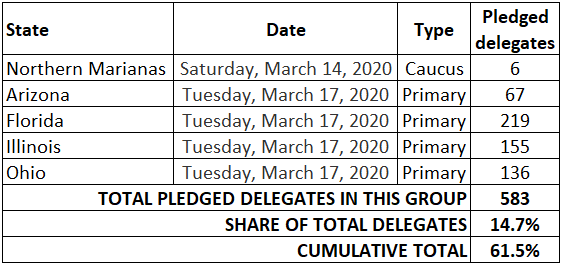

Tuesday, March 17: Super Tuesday, Part Deux

It will surprise no one to hear that both Arizona and Florida are in the top 10 for percentage of Hispanic residents, according to the census. It may be surprising to some that Illinois is also in the top 10.

The Land of Lincoln was one of the closest battles between Clinton and Sanders in 2016, and it probably will again be competitive in 2020, as Illinois represents a great microcosm of the Democratic electorate: The state has significant dense urban and suburban areas, college towns, and rural bastions, as well as a racially and economically diverse electorate. Florida and Ohio also are big sources of delegates, and Arizona — another state where vote-counting will stretch many days after Election Day — is an important general election target for Democrats.

This marks the end of the busiest two-week stretch of the primary. Even though the calendar extends into June, by the time the vote counts are finalized in these states, more than 60% of the pledged delegates will have been awarded. The race may effectively be over at this point; if it is not, there are not that many big prizes that lie beyond it.

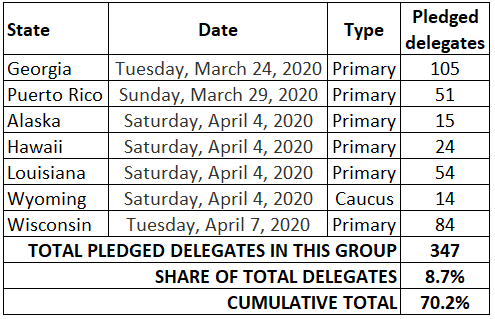

March 24-April 7: The Deep Breath

The pace following March 17 slows considerably. Georgia is a major contest the following week, and we might expect a preview of its eventual results in the other Southern contests held earlier in the month. That also applies to Louisiana on April 4.

The respected Marquette University Law School and Fox News polls have shown Biden, somewhat surprisingly, narrowly leading in Wisconsin, an important general election battleground that will receive a ton of attention on April 7. But the state generally has a progressive/liberal (and largely white) primary electorate, and Sanders or Warren would be a natural favorite in Wisconsin if they are still around at this point.

A three-week intermission follows Wisconsin. It’ll be up to us commentators and analysts to fill the void. Fortunately for us, we’ve had a lot of practice analyzing a presidential primary election with no voting: We’ve been doing it since at least the 2018 midterm.

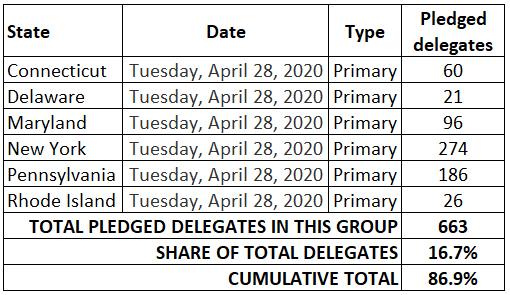

Tuesday, April 28: Acela-ration

This is really the last mega-primary date. A half-dozen states vote, all of which are located in the so-called “Acela Corridor,” named for the somewhat high-speed Amtrak train route that runs from Washington D.C. to Boston. It’s impossible to know what the race will look like at this point, but this was a strong group for Clinton in 2016, and it also includes the state Biden represented in the Senate (Delaware) as well as the one where he was born (Pennsylvania). Bloomberg seems like a natural candidate for parts of Acela-land, too, if he remains a factor at this point.

Even though the primary continues into May and June, 87% of all the pledged delegates will have been awarded by the end of this night.

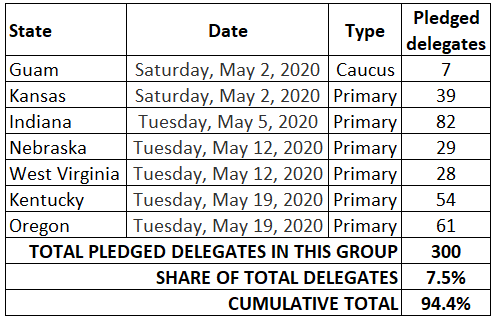

May 2-19: May Days

The May contests are generally in not-very diverse states that, with the exception of Oregon, are reliably Republican these days at the federal level. Sanders performed well in this group in 2016, and some of these states — West Virginia most notably — will feature a significant share of Trump general election voters participating in the primary thanks to vestigial Democratic party registration and identification. In the 2016 West Virginia Democratic primary, about 243,000 voters participated, but Clinton went on to win only about 189,000 votes in the general election.

These kinds of conservative Democrats tended to vote against the frontrunner in both 2008 and 2016, benefiting Clinton in 2008 and Sanders in 2016. Where do they go this time?

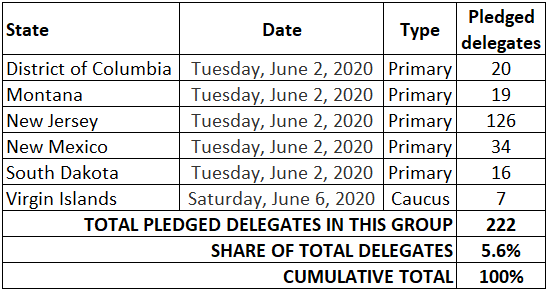

June 2-6: The End (?)

The primary season wraps up, effectively, on June 2, with five contests. In 2016, California voted with this group, leaving a big prize for the end of the calendar. This time, New Jersey is the only state with a substantial number of delegates. The Virgin Islands closes the voting on June 6.

The delegates will gather at the Democratic National Convention from July 13-16 in Milwaukee. The outcome of the primary will determine if it’s the usual coronation — or if it’s something livelier, perhaps livelier than any of us have seen in quite a long time.

These nomination battles have a way of working themselves out, and this one probably will too. But if it doesn’t happen by St. Patrick’s Day — and especially by late April — the Democrats may have a long fight ahead of them.