KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— If Democrats nominated Bernie Sanders, they would, initially, start off with somewhat of a penalty in our Electoral College ratings.

— Sanders’ policy prescriptions and rhetoric may complicate Democratic prospects in the Sun Belt, where the party’s recent growth has been driven by highly-educated suburbanites.

— Given the composition of the 2020 Senate map, which features more Sun Belt states, Sanders’ relative strength in the Rust Belt — assuming that even ends up being the case — nonetheless doesn’t help Democrats much in the race for the Senate.

The Sanders path might be a narrower one

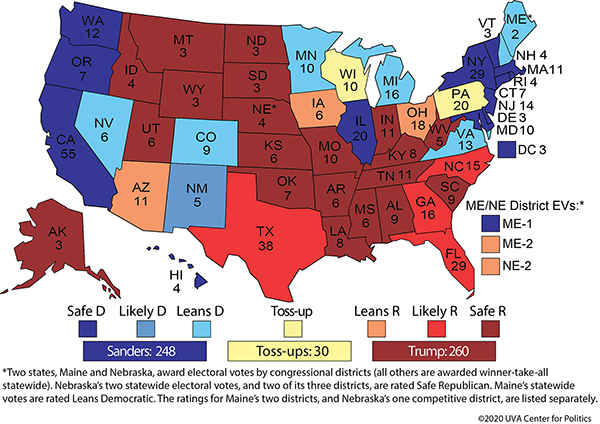

Almost exactly a year ago, we debuted our first ratings of the 2020 Electoral College. Those ratings were based on Donald Trump as the Republican nominee and an unknown Democratic candidate. Since we rolled out these ratings, we’ve tweaked them only mildly. Our current ratings are shown in Map 1.

Map 1: Crystal Ball Electoral College ratings

These ratings reflect a general election in which neither side is clearly favored over the other.

But as Bernie Sanders has ascended to the top of the Democratic pack, and as party elites are starting to sound the alarm about Sanders’ general election prospects, we’re considering how we might change our ratings if Sanders became the presumptive nominee.

The Vermont senator’s campaign of course argues that he would expand the Democratic electorate, as Sanders’ pollster told the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent. Meanwhile, there are reasons to think that the Sanders path is built on a goal, expanding youth participation, that has historically been very difficult to achieve, as David Broockman and Joshua Kalla argued in Vox. Additionally, Sanders does not seem to have as much appeal to white voters with a four-year college degree as some other Democrats.

In our view, we think a Sanders nomination would tilt the election more toward Trump, to the point where the ratings would reflect him as something of a favorite. However, we would not put Trump over 270 electoral votes in our ratings, at least not initially and based on the information we have now.

But these ratings changes would force Democrats to sweep the two Toss-ups, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, and also hang onto the Leans Democratic states, specifically Michigan, that if Sanders proves to be weak will be very much in play.

Here’s what we’re thinking we would do. Map 2 shows hypothetical revised ratings. To be clear, these are not changes we are making to our ratings now, but if Sanders seems to grab ahold of the nomination in the coming weeks, we likely will make most if not all of them.

Map 2: Hypothetical Sanders vs. Trump ratings

The differences between Maps 1 and 2 are as follows: Arizona and the single electoral vote in Nebraska’s Omaha-based Second Congressional District move from Toss-up to Leans Republican; Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas move from Leans Republican to Likely Republican; and Virginia moves from Likely Democratic to Leans Democratic.

Arguably we could or should move Iowa, ME-2, and Ohio into Likely Republican, too, but we’ll give Sanders a little bit of a benefit of the doubt initially as he tries to claw back some working-class white support. If he is able to turn back the clock a bit to an electoral alignment that looks more like 2012, these electoral votes may be more competitive. That does seem unlikely, though, especially as we seem to be constantly reminded of Democratic suburban strength and rural weakness: Just on Tuesday in a pair of special elections, Kentucky Democrats easily held a state House seat in the Cincinnati suburbs, but lost an ancestral Democratic seat in the rural eastern part of the state.

So realistically, these electoral votes (Iowa, ME-2, and Ohio) could shift further toward Trump too.

What we’re doing here is giving the Republicans a boost in places where recent Democratic gains have been fueled by growth in affluent, highly-educated suburbs. Sanders may ultimately replicate Hillary Clinton’s numbers in places like metro Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix. Still, there are reasons to believe that his left-wing economic and governing philosophy, particularly as contrasted with many Americans’ positive views of the economy, may cost the Democrats some support in these places.

Furthermore, in states like Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas, the Democratic nominee just matching Clinton’s 2016 showing in these big metro areas would not be sufficient to win any of those states — after all, Clinton lost all four by 3.5 points or more. Significant overall improvement is required for the Democrats to flip any of these states. This sort of thinking also guides what we would do with the single electoral vote in NE-2, a vote that could be important in a very close Electoral College vote. Trump won the district by about two points in 2016, and it was one of the few marginal swing seats that Republicans held in the 2018 House elections, notably in part because the Democratic nominee was more liberal than many other House Democratic candidates in the midterm.

In one of the Crystal Ball’s first articles of 2020, guest columnist Seth Moskowitz looked at various Democratic paths to 270 electoral votes. Specifically, using 2016’s results as a template, Moskowitz’s analysis hinged on the average raw vote “cost” per electoral vote. Among the takeaways was that Democrats’ most efficient route to 270 was through the Rust Belt. Though some aforementioned Sun Belt states, such as Texas and Georgia, have emerged as increasingly attractive Democratic prospects, they’d require the Democratic nominee to pick up considerably more raw votes compared to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 showing. Given the thin collective margin that Trump carried Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan by in 2016 — fewer than 80,000 votes out of the nearly 14 million they cast — flipping them back into the blue column would require closing a relatively small gap. By contrast, despite the promising trendline there, Clinton’s deficit in Texas was still a daunting 807,000 votes. In this sense, if Sanders were to be the Democratic nominee, he would push the Democrats towards their most logical route to 270 electoral votes.

While Sanders may be helpful in guiding Democrats towards their path of least resistance in the Electoral College, it’s less useful when it comes to the Senate. Aside from winning back the presidency, one of the prime goals of Democratic partisans is to limit the power of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), so the battle for the Senate will be a relevant subplot to the presidential contest.

Thirty-four states will feature Senate races this fall, and a disproportionate number of those states are in the south and west — in other words, states that wouldn’t compliment the coalition Sanders would likely rely on at the top of the ticket, as we suggested last week.

If Sanders flips the trio of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, he’d win the presidency with 278 electoral votes (assuming no states that Clinton carried in 2016 defect to Trump), but at the senatorial level, this path could yield meager returns. Only one of those three, Michigan, has a Senate race — and it wouldn’t even be a pickup opportunity, as freshman Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) is running for reelection.

By contrast, both Senate races that the Crystal Ball currently rates as Toss-Ups fall in Sun Belt states, Arizona and North Carolina. In fact, with a Sanders nomination looking like a more realistic possibility, Democrats’ likely nominee in the Arizona Senate race, former astronaut Mark Kelly, already seems be distancing himself from his party’s frontrunner. In terms of the Senate, we likely would keep Arizona a Toss-up given Kelly’s strengths as a candidate, but Sen. Martha McSally’s (R-AZ) path to victory might get clearer. We also likely would shift North Carolina to Leans Republican and push both Georgia Senate races from Leans Republican to Likely Republican. The potential for Sanders to run behind Clinton might also endanger Democratic Senate odds in places like Colorado, Iowa, and Maine, but as of now we wouldn’t make changes in those states just based on a Sanders nomination.

We also have to be cognizant of the potential of ticket-splitting even if Sanders does do poorly — something we addressed in a New York Times column earlier this week (we leave the House unaddressed in this piece, but see the column for what Sanders might mean for that chamber).

Considering its perception as the quintessential swing state in presidential contests since 2000, seeing Florida rated as Likely Republican might seem crazy. But Sanders really does not seem like a good fit for that state, and for what reason should we give Democrats the benefit of the doubt in Florida? The state is perpetually close, but the party’s losses there for governor and senator in 2018 in the midst of a great Democratic electoral environment represented one of the more counterintuitive electoral results in recent memory (Democratic Senate losses elsewhere in much redder states made more sense).

State analyst and mapper Mathew Isbell attributes the Democratic losses in Florida in 2018 to their underperformance in Miami-Dade County. In 2018, then-Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), and the Democrats’ gubernatorial nominee, then-Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, gained over Clinton elsewhere in the state, but they couldn’t match her showing in the Miami area. Instead of Clinton’s 29 percentage point margin there in 2016, Nelson and Gillum each carried it by a smaller 21 percentage point spread. Rather astoundingly, they each flipped four large Trump counties — St. Lucie, Pinellas (St. Petersburg), Seminole (Orlando suburbs), and Duval (Jacksonville) — but both came up short because of their weaker margins in Miami-Dade County. One-third of the county’s electorate is Cuban; Sanders’ comments praising some aspects of Fidel Castro’s regime could be uniquely toxic with this bloc, and may effectively push Florida out of reach.

Sanders is also a candidate whose strongest appeal is with the young, whereas Florida has an older electorate. According to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Florida’s median age is 41.8 years, and only four states rank higher. Interestingly, other comparatively old states include Maine, New Hampshire, and Sanders’ home state of Vermont, but retirees who can afford to move to Sun Belt states like Florida have typically voted Republican — and perhaps more importantly, they turn out. In 2016, senior citizens powered Trump’s coalition in the Sunshine State. Over 80% of voters 65 and older turned out, and exit polling showed Trump winning this group in a 57%-40% vote. Voters under 30 favored Clinton, but turned out at just 56%; Sanders likely would inspire higher turnout with millennials, but the GOP’s dominance with seniors in Florida has proved to be a potent electoral force.

Conclusion

To be clear, the race for the nomination is not over, and in recent days, Joe Biden has seemed to reassert himself in South Carolina, which may be suggestive of brightening prospects for Biden not just in Saturday’s primary — which at this point we would be extremely surprised if he lost — but in the South more broadly on Super Tuesday. That said, Sanders still finds himself in a better position than any of his rivals overall as the delegate-rich contests of the first three Tuesdays of March loom.

Overall, if Sanders does become the presumptive nominee, we plan to keep an open mind about his candidacy, and the president of course has his own liabilities. But we do think we know enough about the potential weaknesses of Sanders that our reaction to his nomination, if it happens, would be to shift some of the Electoral College against him and also to look at Trump as a small favorite for November.

It would then be up to Sanders to prove the doubters wrong — just like Trump did in 2016.