KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In one of the biggest elections of the calendar year, a Democratic-aligned justice appears favored in next week’s Wisconsin state Supreme Court election. But that was also true in 2019, when a Republican-aligned justice pulled an upset.

— Democrats often underperform in such races in Milwaukee, so that is a key place to watch.

— Judicial voting patterns largely reflect voting in partisan races, but there are some key differences.

Next week’s Wisconsin Supreme Court race

Next week, Badger State voters will head to the polls to weigh in on what has been billed as the most important judicial election of the year. If Democratic-aligned Judge Janet Protasiewicz prevails, liberals will assume a 4-3 majority on the state’s highest court. If voters send Daniel Kelly, a former justice who is effectively the GOP nominee in the contest, back to the body, conservatives will retain control.

From what we can tell, Protasiewicz is a favorite, although given the marginal nature of Wisconsin, we wouldn’t rule out a Kelly win. One indicator has been fundraising. Given the stakes, the race has been expensive: the two sides have combined to spend at least $26 million. Protasiewicz has significantly outspent Kelly, although the latter is getting a late boost from third party groups. Though there has been no public polling, Protasiewicz reportedly leads in private surveys. Early voting has been in progress for over a week, but Wisconsin is a largely Election Day-voting state, so we would not read much into early tallies — indeed, one map that considered the early vote, posted yesterday, has a decidedly “choose your own adventure” feel.

With that, we are going to look at a few areas of the state that may be useful to watch next week. We are assuming anything from a double-digit Protasiewicz win to a narrow Kelly win is possible.

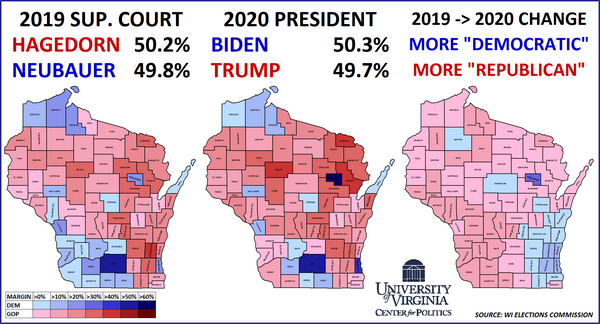

But first, a bit of context. For the tables in this article, we’ll consider returns from 4 recent statewide races. In the 2019 state Supreme Court race, liberal judge Lisa Neubauer was seen as a tenuous favorite but lost to now-Justice Brian Hagedorn, a conservative, by fewer than 6,000 votes. The 2019 result is reason enough to not rule out a conservative win this time. The following year’s election, 2020, went better for Democrats. In the spring, Democratic-aligned Jill Karofsky defeated Kelly, who was appointed to the court in 2016, by a better-than 55%-45% margin. Then, in November, as Joe Biden patched up the Democrats’ Midwestern “Blue Wall,” he narrowly beat Donald Trump in Wisconsin. Though this was not a court contest, we’ll examine some differences between coalitions in partisan and judicial races. Finally, we’ll consider results from late February, which was the “first round” of this contest. As we covered at the time, in a 4-person race, Democratic-aligned candidates combined for 54% of the vote to 46% for the GOP-aligned candidates.

The Blue Bastions

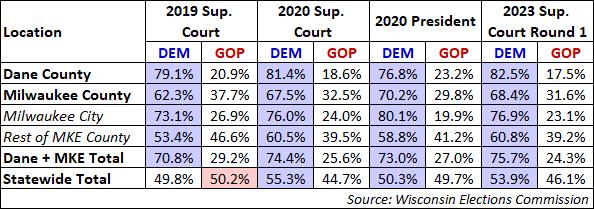

To start, Wisconsin’s two most populous counties are Dane (where Madison is located) and Milwaukee — both are deep blue. As a pair, they typically cast about a quarter of the votes in statewide elections, which gives Democrats a relatively high “floor.” In the 2020 presidential election, Joe Biden netted just over 180,000 votes out of each county. While both counties have voted heavily Democratic in most recent state Supreme Court races, the turnout dynamics don’t always mirror those of presidential (or partisan) races. Table 1 breaks down the 4 recent races there.

Table 1: Dane and Milwaukee counties in recent statewide races

One pattern is that Democratic-aligned state Supreme Court candidates overperformed Biden in Dane while running a few points behind him in Milwaukee. The simple explanation for this seems to be that the Madison electorate is made up of higher-propensity voters. The Democratic base there — including students, University of Wisconsin faculty, other state employees, and white collar professionals — has a front row seat to state government (and all the tumult that has come with it over the past decade or so). In recent presidential elections, Milwaukee County cast upwards of 100,000 more votes than Dane, but in each of the last 3 supreme court races, the pair has been much more evenly balanced (when Karofsky won in 2020, for example, Milwaukee cast 200,000 ballots to Dane’s 196,000). Even while losing statewide, Neubauer came close to surpassing 80% of the vote there, a few ticks better than Biden’s showing 19 months later.

Table 1 separates Milwaukee City, which makes up about 60% of the county’s population, from the rest of the county, which includes a diverse selection of suburbs. Neubauer’s share was 7 points lower than Biden’s in the city itself and 5 points lower in the suburbs — something that proved costly in a close race. Though Karofsky carried the suburbs by a better-than 60%-40% spread, she underperformed Biden in Milwaukee City. As a result, despite doing about 10 points better than Biden statewide, Karofsky did 5 points worse in Milwaukee County.

So the bottom line here is that, if Protasiewicz wins next week, she’ll likely clear 80% in Dane County, but will probably fall short of 70% in Milwaukee County, even if she wins by double-digits. In February, the Democratic performance in Milwaukee tracked closely with Karofsky’s showing — which should put Protasiewicz in a strong position if it holds. If Protasiewicz is stuck in the low-60s in Milwaukee County, though, Kelly may have a path to win.

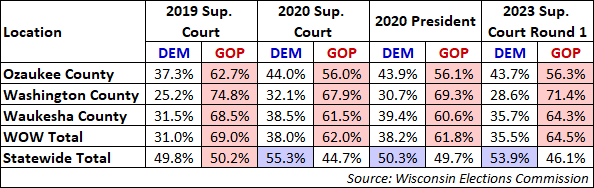

The WOW counties

Though each is exhibiting distinct trends, Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington counties are often grouped into the memorably-named “WOW” counties category — and it is hard to discuss Wisconsin’s electoral landscape without mentioning them. Generally speaking, the WOW counties, which border Milwaukee and take in many of its exurban communities, have been the state’s “GOP heartland” for much of recent history. The area was former Gov. Scott Walker’s (R-WI) electoral bread and butter, and its voters boosted Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) in his come-from-behind reelection win in 2016. In fact, in 2019, Neubauer’s weakness in the Milwaukee area was not limited just to the city and its closer-in suburbs: as Table 2 shows, Hagedorn outpaced subsequent conservative candidates there.

Table 2: WOW counties in recent statewide races

Though Table 1 considers all 3 WOW counties, Waukesha County, which is the most populous, often tracks closely with the group as a whole. Essentially, Ozaukee and Washington counties seem to cancel each other out — the former, which is directly north of Milwaukee City, has seen some blue trends, while Washington, which has a more exurban character, is the reddest of the three.

In February’s result, Republican-aligned candidates combined for 64.5% of the WOW vote, which was an improvement from either of the 2020 contests listed on Table 2. However, both Kelly and his leading GOP-aligned rival, Judge Jennifer Dorow, hailed from Waukesha County, so it seems possible that Kelly has room to fall if Dorow’s voters are not enthusiastic. Put somewhat differently, 15.1% of the total votes in round 1 came from the WOW counties. As Hagedorn won in 2019, that share was a slightly lower 14.9%, suggesting that any Republican enthusiasm from February may be hard to maintain next week, although Dorow was quick to endorse Kelly.

As with the blue counties we discussed earlier, Kelly’s path to victory would be to basically replicate Hagedorn’s showing by carrying the WOW counties by a roughly 70%-30% spread. If Democrats are having a good night, Protasiewicz could keep Ozaukee County within single-digits (actually carrying it may be too heavy a lift) — in that scenario, she would likely be close to 40% among the group as a whole.

As an aside, another important contest will be taking place in the WOW counties on Tuesday, although one on the legislative front. If Republicans win a special election for state Senate District 8, located in the northern Milwaukee metro area, they will claim a supermajority in the chamber. While they could not override Gov. Tony Evers’s (D-WI) vetoes (they are a few seats short of a supermajority in the state Assembly), state Senate Republicans could theoretically impeach officers in other branches of government. In fact, the GOP nominee, state Assemblyman Dan Knodl, recently threatened to vote to impeach Protasiewicz, should he be elected. Donald Trump carried SD-8 by 5 points in 2020, so a Knodl win would not be a surprise.

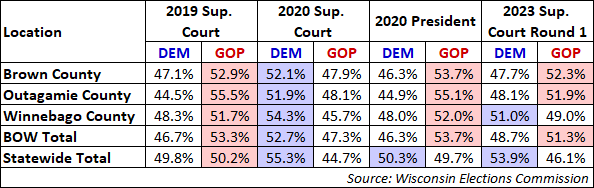

The BOW counties

So, thus far in our survey, we’ve learned that Dane and Milwaukee counties should heavily favor Protasiewicz while Kelly should sweep the 3 suburban WOW counties — in other words, the allegiance of those counties is not in question, it’s just an issue of margin and turnout.

But moving further north, the BOW counties — a moniker that is, by now, well known to followers of state pollster Charles Franklin — are a more marginal group of counties. Sometimes referred to as the major counties of the Fox Valley, the BOW counties consist of Brown (Green Bay), Outagamie (Appleton), and Winnebago (Oshkosh). This manufacturing-heavy stretch usually accounts for 10% of the ballots cast in most statewide elections. Table 3 considers the BOW counties’ voting patterns.

Table 3: BOW Counties in recent statewide races

In each race, every BOW county has voted at least a point or so more Republican than the state. They typically vote together, but not always, and they have some interesting idiosyncrasies. Biden, for example, despite winning the state, performed slightly worse than Neubauer did there a year earlier — a fact that speaks to Biden’s relative strength in the Milwaukee area.

If next week’s vote is close (either way), expect Kelly to carry all 3 by relatively modest margins. But if Democrats are replicating their first-round performance, Protasiewicz will likely at least carry Winnebago, the most Democratic of the trio. In 2012, Barack Obama won the state by a comparable 7-point margin — he carried just Winnebago County while keeping the other 2 very close. Finally, if Prostasiewicz is running away with the race, the dam may break, as it did in 2020 when Karofsky swept the BOW counties.

Blue outside the main metros

Finally, in something of a catch-all category, don’t be surprised if Protasieiwicz carries at least a few Trump-won rural counties — this will probably be necessary, but not sufficient, for a Democratic win. Specifically, keep an eye on the state’s western border. If she is carrying most of the counties in the southwestern corner, that would be a great start, but if she sweeps most of the western border counties, that would probably signal a win.

We say this because, in 2019, Neubauer won over several Trumpy counties in western Wisconsin — she even carried the Obama-to-Trump 3rd District — but was done in by her underperformance in Milwaukee. Map 1 shows the difference.

Map 1: 2019 state Supreme Court vs 2020 president in Wisconsin

So, for Protasiewicz, we’d expect some strength in southwestern Trump counties like Crawford, Grant, and Vernon. In Karofsky’s 10-point 2020 win, she added a few Trump-won counties around the Eau Claire region to her coalition, like Dunn, Jackson, and Pierce — all 3 of those counties favored Democratic-aligned judges. Even further north, Iron County was 1 of 2 Kerry-to-Romney counties in the state, with the other being Pierce. Iron County is smaller and considerably more rural than Pierce, though — Karofsky didn’t carry Iron County, but it narrowly favored Democrats in February. If Protasiewicz holds Iron, it could be another sign that Democrats are beating expectations in rural areas.

Throughout this survey, we’ve emphasized Democratic softness in the Milwaukee metro in past state Supreme Court races, as it has typically manifested to at least some degree. But it’s possible that this year’s contest is so nationalized that a more “presidential” coalition takes form, with Protasiewicz making considerable gains in urban areas while doing worse than expected in the west and north — this would essentially be the opposite of Neubauer’s result.

Finally, to name one last county we’ll be watching, we’ll sneak a more urban county into the non-metro section of the article. We flagged this one in our initial February write up, but Kenosha County, in the southern orbit of Milwaukee, will be interesting. Typically a purple-to-light blue county in state races, it was the scene of nationally-watched riots in the summer of 2020. It has since not voted for any statewide Democrats in partisan races, although Republicans have not carried it in blowouts. Democratic-aligned candidates took a small 50.6% majority there in February, so if Kelly is making up ground, look for Kenosha to turn red again.

Conclusion

Next week’s contest will be the most closely-watched Wisconsin state Supreme Court race since 2011. A dozen years ago, conservatives narrowly came out on the winning side of a contest that was seen as a referendum on then-newly minted Gov. Scott Walker’s anti-union legislation. This time, issues like abortion and gerrymandering seem to be animating the electorate, if asymmetrically so, to the benefit of Democrats. Still, again, we cannot rule out a conservative win.

With that, we’ll end on something that we can be fairly certain of: next week’s race will be a high turnout affair, at least for a judicial race. In February, 961,000 ballots were cast, which was a 36% increase from the 2020 spring primary — it dwarfed the 2016 and 2018 primaries by even larger amounts.