KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In the past decade, four governors faced either a criminal case or sexual misconduct allegations while in office. That may sound like a lot, but it’s actually quite low by recent historical standards.

— Gubernatorial bad behavior peaked between 2003 and 2009, an era personified by such governors as Connecticut Republican John Rowland and Illinois Democrat Rod Blagojevich as well as New York Democrat Eliot Spitzer and South Carolina Republican Mark Sanford.

— There doesn’t seem to be a single reason for the decline in gubernatorial scandals, though declining scrutiny by a shrinking local news media, changes in prosecutorial priorities, and Supreme Court decisions making it harder to prove criminal malfeasance have probably played a role.

— Even as gubernatorial scandals have dwindled, investigations of Congress and key legislative leaders such as state House speakers have remained robust.

A lack of gubernatorial scandal

These may be grim times, with the coronavirus pandemic and its resulting economic downturn. But as governors become key figures in fighting both scourges, the American public appears to be lucky that we’re in something of a golden age for gubernatorial propriety.

In the past decade, there have been four governors to face either a criminal case or sexual misconduct allegations while in office: Virginia Republican Bob McDonnell, Alabama Republican Robert Bentley, Oregon Democrat John Kitzhaber, and Missouri Republican Eric Greitens. McDonnell was term-limited; the other three were forced to leave the governorship under pressure.

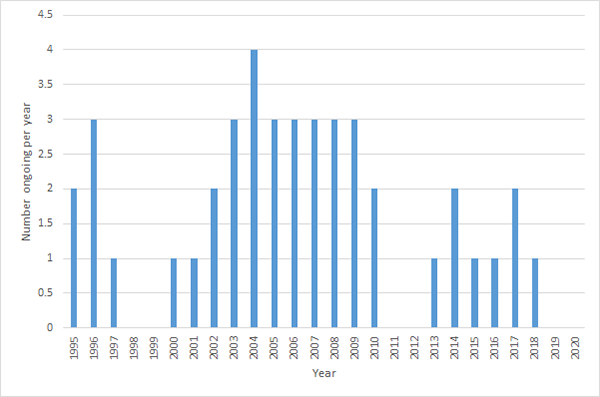

If that sounds like a lot of corrupt and/or scandalized governors, it’s actually not, at least by historical standards. Here’s a chart showing the number of sitting governors who experienced criminal problems or sex scandals in any given year going back a quarter century.

Figure 1: Gubernatorial scandal by year, 1995-present

As Figure 1 shows, gubernatorial bad behavior peaked between 2003 and 2009, the era personified by such governors as Connecticut Republican John Rowland and Illinois Democrat Rod Blagojevich (both of whom went to prison) and New York Democrat Eliot Spitzer and South Carolina Republican Mark Sanford (who had sex scandals while in office).

All told, between 2003 and 2009, slightly more than three sitting governors, on average, were experiencing legal issues or sexual misconduct allegations.

By contrast, since 2011, the average has been less than one scandal at a time. And compared to the earlier generation of scandals, they’ve tended not to drag on very long, and as such did little to hamper state governance.

For instance, the scandal involving Kitzhaber, which involved the use of state resources to aid his fiancee, Cylvia Hayes, was public for less than six months, and it ended with Kitzhaber’s resignation just weeks after taking the oath of office for his fourth term. Greitens, meanwhile, resigned amid allegations of blackmail related to a woman with whom he was having an affair; his resignation occurred less than five months after the allegations became public. (Related criminal charges were dropped.)

I’ve used a pretty strict definition to calculate these numbers; there were also more borderline cases in the first decade of the century than in the second.

In my analysis here, I’ve followed the guidelines I used in my two previous columns on this subject for Governing in 2013 and 2016: I’ve included governors only if the governor’s troubles became publicly known while he was still in office. (I’d say “he or she,” but not a single female governor made this list.)

In measuring how long a governor’s scandal lasted, I started the count when serious questions began being aired publicly, and I stopped counting when they left office, even if their troubles persisted after their departure. For this article, I’m also ignoring letters sent in late August by the head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division to four Democratic governors (Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania, Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Phil Murphy of New Jersey, and Andrew Cuomo of New York) over their handling of nursing homes during the coronavirus crisis.

Here’s the dishonor roll:

Elected 1990

Arizona Republican J. Fife Symington was convicted of seven felony counts of fraud in 1997 and resigned office. His conviction was later overturned and Symington was pardoned by President Bill Clinton. (Duration of scandal: 1996-97)

Elected 1991

Democrat Edwin Edwards of Louisiana went to prison in 2002 for bribery related to casino licenses. (Duration of scandal: 1995)

Elected 1992

Democrat Mike Lowry of Washington state settled a sexual harassment claim by a former aide, denying wrongdoing but paying the plaintiff $97,500 and agreeing to sexual harassment training sessions. He declined to seek a new term after the revelations. (Duration of scandal: 1995-1996)

Elected 1994

Arkansas Democrat Jim Guy Tucker was convicted in 1996 of charges related to the Whitewater scandal and resigned office. (Duration of scandal: 1996)

Rowland pled guilty in 2004 to corruption-related charges and resigned office. (Duration of scandal: 2003-2004)

Kentucky Democrat Paul Patton admitted to an improper role in promoting an employee at the request of Tina Conner, a woman he was having a relationship with. Ultimately, he admitted to two violations, paid a $5,000 fine, and faced a public reprimand. (Duration of scandal: 2002-2003)

Elected 1998

Republican George Ryan of Illinois was convicted in 2006 for corruption-related charges. (Duration of scandal: 2000-2002)

Ohio Republican Bob Taft pleaded no contest to violating state ethics laws in 2005. He remained in office. (Duration of scandal: 2005-2006)

Elected 2000

Democrat Bob Wise of West Virginia acknowledged an affair in 2003 and announced he would not seek re-election the following year. (Duration of scandal: 2003-2004)

Elected 2001

Democrat Jim McGreevey of New Jersey acknowledged an affair with a male former appointee who claimed sexual harassment. He resigned his office. (Duration of scandal: 2004)

Elected 2002

Blagojevich, after years of investigations, was impeached in 2009 and convicted of corruption-related charges in 2010 and 2011. The Democrat served part of a 14-year prison sentence before it was commuted by President Donald Trump. (Duration of scandal: 2004-2009)

Sanford disappeared from the state in 2009, first telling reporters he was hiking the Appalachian Trail. After his return, it was discovered he was having an extramarital affair and had traveled to Argentina to see the woman. Ultimately, Sanford was censured by the state legislature. (Duration of scandal: 2009-2010)

Elected 2003

Republican Ernie Fletcher of Kentucky was investigated for subverting the state’s hiring system; after being indicted, he reached an agreement with the state attorney general that resulted in the charges being thrown out. (Duration of scandal: 2005-2007)

Elected 2006

Nevada Republican Jim Gibbons experienced several controversies starting from the day he was elected, including allegations of sexual assault (which resulted in no criminal charges) and a gifts-for-contracts scheme (for which he was cleared by the Justice Department in 2008). He also was found to have exchanged hundreds of texts on a state cellphone with a woman who was not his wife; this became a factor in a messy divorce. (Duration of scandal: 2007-2010)

Democrat Eliot Spitzer of New York resigned after acknowledging that he had been seeing a prostitute. (Duration of scandal: 2008)

Elected 2009

McDonnell was found guilty of public corruption charges, but the conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2016. (Duration of scandal: 2013-2014)

Elected 2010

It took the gubernatorial class of 2010 — which included 23 governors — six years to produce its first scandal-tinged member.

That would be Bentley, who was caught saying sexually explicit things to his senior political advisor, Rebekah Caldwell Mason, on a leaked audio recording. Facing impeachment, Bentley resigned in 2017 and pled guilty to two misdemeanor campaign finance charges. (Duration of scandal: 2016-17)

Elected in 2014 (final term of office)

Kitzhaber (Duration of scandal: 2014-15)

Elected in 2016

Greitens (Duration of scandal: 2017-18)

A number of governors don’t make the cut for this list. From the previous decade, I excluded several governors whose administrations faced ethical or legal controversies but were either cleared or never directly charged. These include Republican Judy Martz of Montana, Republican Frank Murkowski of Alaska, Democrat Bill Richardson of New Mexico, Democrat Jim Doyle of Wisconsin, and Republican Matt Blunt of Missouri. And two governors had convictions that emerged only after they were term-limited (North Carolina Democrat Mike Easley) or lost a bid for a second term (Alabama Democrat Don Siegelman).

A few more recent controversies also fall short of inclusion. Aides to New Jersey Republican Chris Christie — but not Christie himself — faced charges over 2013 lane closures on the George Washington Bridge, the controversy known as “Bridgegate.” Kentucky Republican Matt Bevin faced scrutiny for questionable pardons, but that came after he’d lost and left office. And West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice faces ongoing investigations, but they relate to the billionaire’s business holdings and largely predate his ascension to the governorship.

So why are there so few gubernatorial scandals these days? Here are some possibilities:

Luck and timing: Both of the periods when there were zero gubernatorial scandals came after elections with large classes of incoming governors — 2010 and 2018. So it could be as simple as new governors not having time to turn bad.

“Corruption often creeps in after a public official has been in office for a while, and there may not yet have been time for newcomers to commit crimes or for investigations to be completed,” said Barbara McQuade, a University of Michigan law professor and the U.S attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan between 2010 and 2017.

Rise of the ideologues: Politicians today seem less likely to view government as a source of spoils. Instead, the motivating factor is more likely to be partisanship and the culture war. That makes traditional types of corruption less appealing.

A shrinking local media: The number of statehouse reporters has decreased dramatically in recent years, with veteran journalists retiring or taking buyouts and some news organizations closing statehouse bureaus entirely. This reduces the amount of fodder for investigations and scandals.

“Local newspapers continue to lose staff and resources, and that could make a difference,” said Michael D. Gilbert, a University of Virginia law professor.

Deterrence due to digital detection: “Technology permits investigators to track electronic communication, the movement of money and even location,” McQuade said. “Officials know it is not as easy to get away with corruption as it was in the old days.”

Prosecutorial changes: Prosecutors “may be allocating resources elsewhere,” said Juliet Sorensen, a Northwestern University law professor.

There is some data to support this theory. White-collar criminal cases, of which corruption cases are one type (though far from the only one), have fallen consistently since their most recent peak in 2011. In 2019, federal white-collar cases hit their lowest level in at least 33 years and are now just over half of their level in the 1980s and 1990s.

Public corruption cases “are hard to detect and hard to prove, so they take a lot of resources,” said Randall D. Eliason, a George Washington University law professor and former assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia specializing in public corruption cases. “Law enforcement is a finite resource, and every administration sets priorities. So if you have a greater focus on immigration, or drugs, or violent crime, for whatever reason, you can see a drop-off in public corruption cases.”

Changes in legal interpretations: Perhaps the biggest change has been in jurisprudence. “Corruption cases are just a lot harder to prove than they were 10 or 20 years ago, because the legal theories used to pursue such cases have been dramatically curtailed,” Eliason said.

In 1999, the Supreme Court ruled in U.S. v. Sun-Diamond Growers of California that a gratuity to an official must be directly linked to an official act for criminal law to apply; a series of ongoing gifts without linkage is insufficient for a conviction. Then, the 2010 case Skilling v. U.S. curtailed the use of honest services fraud cases, which some prosecutors had turned to after the Sun-Diamond ruling.

In 2016 came the ruling that overturned Bob McDonnell’s conviction; it narrowed the definition of “official act” to exclude actions like arranging meetings or making phone calls in exchange for secret gifts. And earlier this year, the Supreme Court threw out the Bridgegate-related convictions, arguing that “not every corrupt act by state or local officials is a federal crime.”

The string of Supreme Court cases “has left us with a system in which only the most clumsy and obtuse corrupt officials will end up being prosecuted,” Eliason has written.

Other targets may be juicier: It’s worth noting that even as gubernatorial scandals have declined, congressional scandals have remained common. Just in the past two years, Republican Reps. Duncan Hunter of California and Chris Collins of New York have left Congress due to criminal investigations.

More intriguingly, powerful state legislators seem to have become bigger targets for criminal investigations in the past half-decade.

In a case that has taken years to sort out, some of the corruption and money laundering convictions of former New York Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver have been upheld.

In addition, former speakers Bobby Harrell of South Carolina and Gordon Fox of Rhode Island resigned amid criminal cases, and former Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard was convicted on 12 felony corruption counts.

Earlier this year, Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder was arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit racketeering as part of a nuclear plant bailout he helped pass.

Also this year, Illinois’ largest utility, ComEd, settled a case with federal prosecutors that focused on secret payments to allies of long-serving Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan; Madigan has not been charged and remains in his position.

Why might legislative leaders have become more attractive targets for prosecution? My former Governing colleague Alan Greenblatt has suggested that even powerful lawmakers attract less media and public scrutiny than governors do, which might give them a false sense of security.

In addition, even the top legislators often represent small, safe districts where voters may give them more running room than a governor who has to woo a broad coalition of voters statewide. Another former Governing colleague, Alan Ehrenhalt, has suggested that the low salaries paid to legislators often require that they, unlike governors, hold outside jobs that can bring a host of potential conflicts of interest.

| Louis Jacobson is a Senior Columnist for Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He is also the senior correspondent at the fact-checking website PolitiFact and was senior author of the 2016, 2018, and 2020 editions of the Almanac of American Politics and a contributing writer for the 2000 and 2004 editions. |