KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Presidential party midterm losses are a regular feature of American politics.

— President Biden’s numbers are weak as well. But it may be that Democrats are insulated in some ways from a potential “shellacking.”

— Democrats are very likely to lose their House majority, although their total net loss is very likely to be smaller than in some past GOP wave years simply because the Democratic majority is already so small.

— The composition of this year’s Senate map gives the Democrats a fighting chance to hold their majority there.

Does a Democratic “shellacking” loom?

One of the most regular patterns in American politics is the tendency of the president’s party to lose seats in Congress in midterm elections. The president’s party has lost House seats in 17 of 19 midterms and Senate seats in 13 of 19 midterms since World War II. Across all 19 midterm elections, the president’s party has lost an average of about 27 seats in the House and roughly 3.5 seats in the Senate.

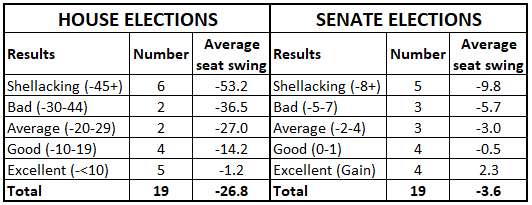

While midterm elections rarely bring good news for the occupant of the White House, the magnitude of the losses suffered by the president’s party can vary widely. Not every midterm election results in a “shellacking,” as President Obama famously described the results of the 2010 midterm in which his party lost 64 seats in the House and 6 seats in the Senate. Table 1 presents a classification of midterm elections since World War II based on the magnitude of the losses suffered by the president’s party.

Table 1: Categorizing midterm results for president’s party, 1946-2018

Source: Data compiled by author

Based on this classification scheme, between one-fourth and one-third of midterms have resulted in a “shellacking” for the president’s party. The president’s party lost an average of more than 50 House seats and almost 10 Senate seats in these elections. At the other end of the spectrum, there have been 5 midterms in which the president’s party lost fewer than 10 seats in the House, including 2 elections in which the president’s party gained seats. Likewise, there have been 4 elections in which the president’s party gained seats in the Senate and another 2 where there was no net change.

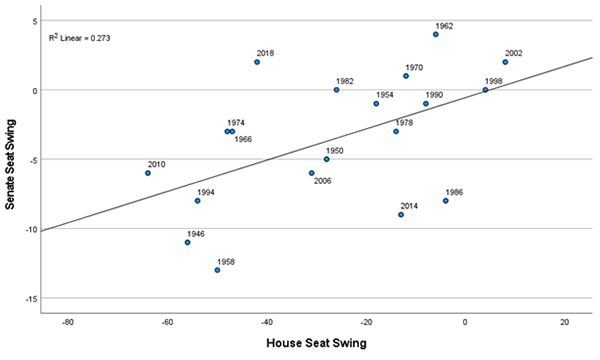

Figure 1: Senate seat swing by House seat swing in midterm elections, 1946-2018

Source: Data compiled by author

It is important to note that midterm elections do not always produce consistent results when it comes to House and Senate seat swing. As the data in Figure 1 demonstrate, there is only a modest relationship between the House and Senate results — the correlation between the 2 is only .52. While a few midterms, like 1946 and 1958, have resulted in a double shellacking, others have produced inconsistent results. In 2018, for example, Republicans actually won 1 more Senate seat than they had won in 2016 while suffering a near-shellacking in the House, with a loss of about 40 seats.

What to expect in 2022

There appears to be a growing consensus among pundits and political observers that Democrats are likely to experience a shellacking in the 2022 midterm elections, especially in the House of Representatives. According to observers such as Chuck Todd and Mark Murray of NBC News, a number of indicators are now pointing toward major losses for Democrats, especially President Biden’s poor approval rating and the large proportion of Americans who believe that the country is currently on the wrong track or headed in the wrong direction.

But while the fact that Biden’s approval rating has been mired in the low 40s for months is clearly a danger sign for Democrats, historically presidential approval has not been a very accurate predictor of midterm seat swing. For the 19 midterm elections since World War II, the correlation of net presidential approval (approval-disapproval) with House seat swing is a rather modest .66 while the correlation with Senate seat swing is a weak .36. Presidential approval explains only 44% of the variation in House seat swing and only 13% of the variation in Senate seat swing. Unfortunately, data on the “right track/wrong track” question are only available for the last 10 midterm elections, so it is difficult to assess its value as a predictor of midterm outcomes.

One indicator that has been shown to produce more accurate forecasts of both House and Senate seat swing than presidential approval is the generic ballot — a question in which voters are asked which party they plan to vote for without providing names of individual House or Senate candidates. By combining the results of generic ballot polling with the number of House or Senate seats that the president’s party is defending in each election, we can produce reasonably accurate forecasts of seat swing, although these predictions are more accurate for House seat swing than for Senate seat swing.

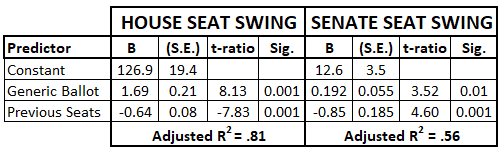

Table 2: Regression analyses of seat swing in midterm elections, 1946-2018

Source: Data compiled by author

Table 2 displays the estimated regression coefficients for the generic ballot model for House and Senate midterm elections between 1946 and 2018. The two predictors — generic ballot margin for the president’s party and seats at stake for the president’s party — have highly significant effects for both House and Senate elections. The model explains over 80% of the variance in House election outcomes and almost 60% of the variance in Senate election outcomes. The results in Table 2 indicate that a shift of 10 points on the generic ballot produces a swing of about 17 seats in the House and 2 seats in the Senate. The results also indicate that for every additional 10 seats that the president’s party holds in the House going into a midterm election, it can expect to lose an additional 6.4 seats and for every additional 10 seats the president’s party has at stake in the Senate, it can expect to lose an additional 8.5 seats.

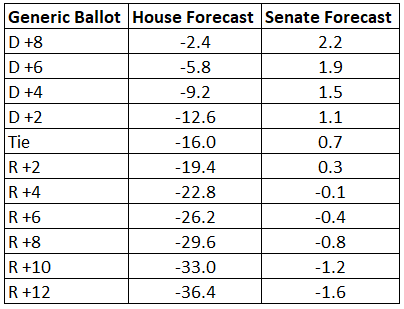

Table 3: Predicted change in Democratic seats in 2022 midterm election

Source: Data compiled by author

Based on the estimated coefficients in Table 2 we can make conditional forecasts of House and Senate seat swing in the 2022 election depending on generic ballot polling in the fall. The results in Table 3 indicate that, based on recent generic ballot polling compiled by FiveThirtyEight in which Republicans have held an average lead of just over 2 points for several weeks, Democrats can expect to lose about 19 seats in the House and break even in the Senate. Of course, there is a margin of error associated with the predictions. Based on the standard errors of estimate for the two models (approximately 10 seats for the House model and approximately 3 seats for the Senate model), we can say that there is a high probability that Democrats would lose between 9 and 29 seats in the House. The likely range of Senate outcomes goes from a loss of 3 seats to a gain of 3 seats.

The results in Table 3 indicate that while Democrats are unlikely to experience a shellacking in 2022 along the lines of the losses suffered by the party in 1994 or 2010, they are almost certain to lose their majority in the lower chamber. Even if they were to hold a modest lead on the generic ballot in the fall, they would be likely to lose more than the 5 seats that would cost them their majority. On the other hand, the Senate forecast indicates that Democrats have about an even chance of holding onto control of that chamber.

The key factor limiting the likely size of Democratic losses in the House and offering them hope of maintaining control of the Senate is the numbers of seats at stake in the 2 chambers. While the extremely small size of the Democratic majority in the House makes it very likely that they will lose control of the chamber, it also reduces the magnitude of their expected losses. For example, if Democrats currently held 252 seats in the House instead of 222, their expected losses would jump from 19 to 38.

In the Senate, seats at stake has an even stronger impact. If Democrats were defending 20 seats this year instead of only 14, their expected losses would jump from 0 to 5. The fact that the class whose seats are up for election in 2022 is disproportionately Republican is what gives Democrats a reasonable chance of maintaining control of the chamber.

Conclusion

Democrats are very likely to lose their majority in the House of Representatives in the 2022 midterm election and could lose their majority in the Senate, although that is less certain. In neither chamber, however, are they likely to experience a shellacking of the sort that both parties have experienced in some postwar midterm elections. That is simply because they won only 222 seats in the House in 2020 and are defending only 14 seats in the Senate. The fact that very few of those Democratic seats in the House and none of the Democratic seats in the Senate are in districts or states that were carried by Donald Trump in 2020 makes it even less likely that the party will experience a shellacking the size of which we’ve seen in some previous midterms or anything close to it — even as the Republicans could very well flip both chambers of Congress this fall.

Alan I. Abramowitz is the Alben W. Barkley Professor of Political Science at Emory University and a senior columnist with Sabato’s Crystal Ball. His latest book, The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump, was released in 2018 by Yale University Press. Alan I. Abramowitz is the Alben W. Barkley Professor of Political Science at Emory University and a senior columnist with Sabato’s Crystal Ball. His latest book, The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump, was released in 2018 by Yale University Press. |