KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— President Joe Biden and his party are struggling amidst myriad challenges, including high gas prices. Gas prices have spiked in recent weeks following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

— There is some association between higher gas prices and lower presidential approval, although the connection is not particularly strong.

— This association has been weaker over the past decade than it was previously.

Fueling presidential approval

With inflation at a roughly 40-year high, the electorate appears to be focusing on high prices. A Wall Street Journal poll released late last week showed that about half of voters named inflation and the economy as the top issue they want the federal government to address, far more than any other issue. More than 6 in 10 respondents (63%) disapproved of President Biden’s handling of rising costs, and respondents gave Republicans a 17-point edge when asked which party was better-equipped to handle the issue.

An unmistakable reminder of high prices comes from gas station signs on street corners across the country, which have shown steadily rising gas prices over the course of the Biden presidency. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the “real” (meaning adjusted for inflation and expressed in today’s dollars) price of gas in January 2021, when Biden took office, was $2.51, and it had climbed to $3.53 last month. That doesn’t take into account the first couple of weeks of March, as gas prices spiked over $4 per gallon.

Now, there are all sorts of reasons that go into this. One is that gas prices dipped in 2020 thanks to pandemic-related disruptions to travel plans, creating pent-up travel demand that was realized in 2021. Another factor, more recently, is the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has caused ripple effects in the global oil market (Russia is a major oil producer). There are lots of other contributors, many of which are subject to debate and surely will be hashed out in the looming midterm campaign (such as Republican accusations that Biden and Democrats are too hostile to domestic fossil fuel production).

We’re not trying to explain why gas prices are up. Rather, the recent spike in gas prices raises a key question: Is there any connection between high gas prices and presidential approval?

The short answer is that there appears to be some connection between higher gas prices and lower presidential approval, but the connection is not that strong, and it has become weaker in recent years.

Our former colleague Isaac Wood looked at this back in 2011, and we’re updating his research here.

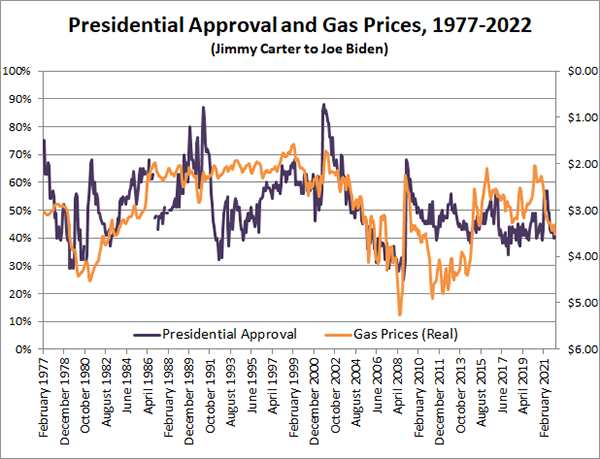

Figure 1 shows the trends in both presidential approval and gas prices from the first full month of Jimmy Carter’s presidency (February 1977) through the most recent full month of Joe Biden’s presidency (February 2022).

The purple line shows the president’s monthly approval rating, as measured by Gallup, which has regularly tracked presidential approval ratings for the entirety of the time period studied here. The orange line shows the real price of regular gasoline as measured in today’s dollars, but note that while the y-axis scale measuring presidential approval (on the left) goes from lowest to highest as one moves up the scale, the y-axis scale measuring gas prices (on the right) goes from highest to lowest as one moves up the scale. This is a way to visualize how high gas prices might exert some “downward” pull on a president’s approval rating. If high gas prices do in fact contribute to low presidential approval ratings, one might expect that as gas prices rise (and the orange line goes down on our Figure 1), presidential approval would also dip along with those high prices. You can click on Figure 1 to see a larger version of the image with a bit more detail.

Figure 1: Presidential approval and gas prices, 1977-2022

Note: A few months of presidential approval are omitted because Gallup did not release approval polls during those months.

Sources: Gallup, U.S. Energy Information Administration

Just in eyeballing Figure 1, there are some connections we can make. The highest real gas prices over the 45-year span covered came in 2008, a time of economic strife in which George W. Bush had very poor approval ratings as he finished his presidency. One can see a dip in Bush approval that appears correlated with the very high gas prices of that era. But it would also be a leap to say that the gas price spike was the sole reason for Bush’s poor approval ratings. Remember that correlation does not necessarily imply causation.

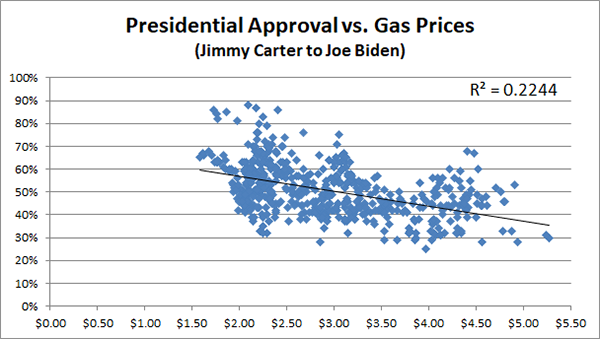

Speaking of correlation, we calculated the correlation between real gas prices and presidential approval over this time period. We found that there was a -.47 correlation between those 2 variables. The r-squared value measuring the connection between the 2 variables was just .22 (this is on a scale of 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no association between the 2 variables and 1 indicating a perfect association). This is shown in the scatterplot between presidential approval and real gas prices, Figure 2.

Figure 2: Scatterplot of presidential approval vs. gas prices

Sources: Gallup, U.S. Energy Information Administration

This means that there was some association between higher gas prices and lower presidential approval (hence the negative correlation). But the correlation is not particularly strong.

Interestingly, the correlation figure is lower for the longer 1977-2022 timeframe than it was for just 1977-2011, when the Crystal Ball last looked at this. Back then, the correlation for that timeframe was -.52 (with an r-squared of .27).

There’s hardly been any correlation at all if one just looks at April 2011 through February 2022 — the correlation is .09, so the direction of the relationship has changed (going from negative to positive), but the correlation is so low that there was hardly any association between gas prices and presidential approval over the past decade or so (the r-squared was basically 0).

We also looked at whether lower gas prices are associated with higher presidential approval. We did not find any indication that there was an association between gas prices and presidential approval when gas prices were low, both back in 2011 and now in 2022. So it may be that while presidents can be punished to some degree for higher gas prices, they may not be rewarded when gas prices are lower.

Conclusion

It makes some sense that whatever the connection between gas prices and presidential approval is, the connection might be weaker now than in the past, simply because presidential approval ratings are not as dynamic as they used to be. Both Barack Obama and (especially) Donald Trump had remarkably stable approval ratings, and Biden’s has not jumped around much either, declining from the mid-50s at the start of his term to the low 40s now.

And most recently, consider this: Even as gas prices have spiked in the past couple of weeks in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Biden’s approval rating has actually gone up slightly, as measured by the FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics averages. His average approval in both on March 1 was 41% approve/54% disapprove; as of Wednesday, his approval was up about 1-2 points and his disapproval was down about 1-2 points in both averages.

Biden may be experiencing a minor “rally-around-the-flag” effect as the nation watches the war unfold in Ukraine. He also may have received a tiny bump from his State of the Union address, delivered on March 1. Regardless, this most recent round of gas price spikes hasn’t pushed his approval further downward. But, over the long run, have higher gas prices since Biden took office contributed to his declining standing? Quite possibly, but it’s difficult to prove and there likely are a lot of other reasons that have contributed to his decline.

That a president would prefer to have lower gas prices than higher ones is obvious. That high gas prices actually do contribute to lower presidential approval is not as obvious, although there is some limited evidence for it based on what we’ve found in our research. But we also are in an era of fairly stable presidential approval ratings, meaning that it shouldn’t be surprising that whatever impact a single factor (gas prices) might have on presidential approval, the importance of that factor might be declining.