| Dear Readers: The event scheduled for Friday evening featuring law enforcement officers who defended the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 has been postponed. Keep your eye on this space for more information about this event and other upcoming Center for Politics programs this winter and spring.

— The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The GOP’s House majority begins today with what could be a historic vote — or votes — for Speaker of the House.

— Kevin McCarthy and George Santos, the focus of so much recent House coverage, may end up being short-termers as, respectively, Speaker of the House and a member of the House. But it would be hard for either to break records for brevity of service.

— Voters in 2022 did what midterm voters often do — put a check on the White House.

— But the 2022 verdict was so mixed that the House majority is once again up for grabs in 2024.

The House at the dawn of a new GOP majority

The pair of biggest developments in the U.S. House over the holiday season prompted us to look at the history books. Our queries were: What is the shortest-ever tenure for a U.S. House member, and what is the shortest time anyone has served as Speaker of the House?

The reason we were pondering both questions is that Rep.-elect George Santos (R, NY-3) is under fire for lying about much of his past and House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-20) is struggling to secure the votes he needs to become speaker in a vote slated for later today.

But the tenures of both Santos as a member and McCarthy as speaker would have to be vanishingly brief to make history: The shortest time served by any House member, and by any speaker, is in both instances just a single day.

Effingham Lawrence, a Louisiana Democrat, served for the final day of the 1873-1875 Congress — he was seated on March 3, 1875 after successfully contesting his opponent’s victory in 1872. The new Congress began the following day, and Lawrence was not a part of it.

Theodore Pomeroy, a New York Republican, served just a day as Speaker of the House in 1869, replacing Schuyler Colfax, who resigned before becoming vice president under Ulysses S. Grant. Pomeroy had not sought reelection in 1868, so he had a single day as speaker, March 3, 1869. He then left the House as the new Congress began the following day.

Santos becomes a member of the House at noon today (Tuesday, Jan. 3), according to the 20th Amendment. So as long as he does not resign sometime between taking office and Wednesday, he won’t be setting a record for shortest tenure. As to Santos’s longer-term future, he may eventually be compelled to resign. But despite his fabrications, the House would very likely be overstepping its constitutional bounds to prevent Santos from taking office. The R Street Institute’s James Wallner, a former senior Republican Capitol Hill staffer and an expert on congressional procedure, explained why, and also what avenues the House does have to hold Santos accountable. Former federal prosecutors Andrey Spektor and Matt Jacobs, writing for NBC News, recently noted that any indictment of Santos would “likely depend on the content of personal and campaign-related financial documents that he, like all candidates for federal office, are required to submit.” On Monday, the New York Times reported that Brazilian authorities are reviving a fraud case against Santos regarding an almost 15-year-old incident there involving a stolen checkbook. Santos’s history — whatever his history actually is — appears to be catching up to him.

While a number of Republicans have spoken critically of Santos, McCarthy has not. This may be in large part because in a conference of only 222 members, McCarthy needs every vote for speaker that he can get. Assuming McCarthy does become speaker — a major and quite possibly erroneous assumption, as of this writing (Tuesday morning) — one would expect him to last in the job for at least a day. But even if he gets the job, he may not last particularly long given the difficulty he has had in trying to lock down the top job in the chamber.

There has not been a second ballot in a speaker election in 100 years. If it happens, a multiple-ballot speaker election would be the House equivalent of a “contested” presidential nominating convention — something we have not seen in a very long time, and something that could unfold in quite unpredictable ways, particularly the longer it drags on.

Santos’s travails, and McCarthy’s, take place in the context of a narrowly divided House. Republicans will have a 222-212 majority as of now, with the Democratic side reduced by one following the death of Rep. Donald McEachin (D, VA-4) in late November. McEachin is very likely to be replaced by state Sen. Jennifer McClellan (D) in a Feb. 21 special election. McClellan won the Democratic nomination for the seat in blowout fashion in a firehouse primary decided a few days before Christmas. The House is otherwise, at least for the moment, at full strength.

That the House’s Republican strength is not as robust as perhaps it could or should be is part of McCarthy’s math problem. An unnamed House Republican who is on the fence about backing McCarthy, speaking to Politico’s Playbook, cited this reality: McCarthy “failed to produce the kind of majority to make us irrelevant,” referring to McCarthy’s detractors within the House GOP ranks. Previous speakers have had to endure defections in recent speakership votes, but many of those basically just amounted to protest votes. The stakes are more real this time.

As are the electoral stakes. The House ended up being effectively a Toss-up in both the 2020 and 2022 elections, even though it didn’t feel like that to many (including us) in the leadup to both of those elections. The race for control certainly starts as a Toss-up for this cycle.

It’s unusual, although not unprecedented, for 2 consecutive elections to produce such small majorities. The Republicans’ full-strength 222-213 edge is the same as the majority the Democrats won in 2020. That is similar to the Houses elected in 1998 and 2020 — effectively 223-212 and 222-213 Republican, respectively, in those 2 elections (we say “effectively” because we are allocating a few independents into the major-party columns). Republicans ended up building a more durable edge in 2002, 1 of just 2 midterms since World War II where the president’s party netted House seats (1998 is the other). The popularity of George W. Bush following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks paired with some GOP redistricting/reapportionment advantages help explain why that happened.

If Republicans hold the majority in 2024, redistricting may also be a factor: For a variety of reasons, Republicans may be able to enact new gerrymanders in North Carolina and Ohio, perhaps netting them, combined, several extra seats.

However, we’ve also noted previously that Republicans are arguably more “overextended” in the House than Democrats are: Republicans hold 18 districts that Joe Biden carried in the 2020 presidential election, while Democrats hold only 5 districts that Donald Trump carried. Several of these members — Santos foremost among them, if he ends up as a candidate next year — should be quite vulnerable in a presidential year. (Santos has reportedly told New York Republican leaders that he won’t run for reelection, according to Politico’s Olivia Beavers.)

But Democrats also hold a majority of the most competitive seats, which gives Republicans a lot of offensive targets, too.

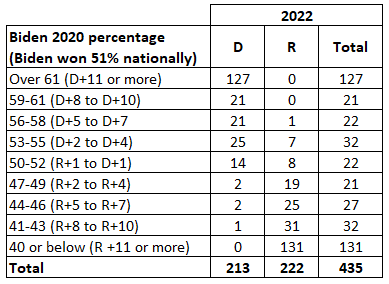

The House is well-sorted based on presidential partisanship. Table 1 classifies the districts based on 2020 presidential performance. Joe Biden got 51% of the vote in 2020, which is effectively the midpoint of the table. Districts where he got between 50%-52% of the vote are the R+1 to D+1 range. Districts where he got between 53%-55% are D+2 to D+4, while those where he got 47%-49% are R+2 to R+4, and so on and so forth. In a previous article looking at the recent history of House midterms and how the parties performed in these categories of seats, we defined the R+4 to D+4 range as effectively the competitive zone in the House. While parties can win unfavorable seats outside of that range, they have found it increasingly difficult to do so.

Table 1: 2022 House results by 2020 Biden performance category

Note: Biden performance is rounded to the nearest whole number

Source: Dave’s Redistricting App for 2020 presidential performance by district

Of the 435 House seats, just 75 are in that most competitive range (R+4 to D+4, or Biden 47% to 55%). Democrats actually have a small edge, 41-34, among these districts. Democrats also hold 3 districts where Biden got less than 47% (R+5 or greater) — Rep.-elect Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (D, WA-3) and Rep. Jared Golden (D, ME-2) carried districts where Biden got about 46% of the vote, and Rep. Mary Peltola (D, AK-AL) won the at-large statewide district in Alaska, where Biden got about 43% of the vote. Republicans hold just a single district where Biden won 56% of the vote or more (D+5 or greater) — the suburban New York City seat that Rep.-elect Anthony D’Esposito (R, NY-4) flipped in November gave Biden nearly 57% in 2020. This seat is located directly south of NY-3, the Nassau County-based district Santos flipped last fall that gave Biden a little more than 53% of the vote.

Republicans are aided by the fact that there are 190 districts that are R+5 or greater, but only 170 that are D+5 or greater. Still, in a closely-divided House, there are enough districts in the competitive zone that the majority remains up for grabs.

Despite a disappointing overall performance for Republicans, voters in the past midterm did do what they often do in midterms: take the House away from the president’s party. The House has now changed hands 12 times since 1900, and 10 of those changes in control came in midterm years. Each time, the party that did not hold the White House flipped the House from the presidential party. The 2 exceptions, when the House flipped in presidential years, came in consecutive presidential elections, Harry Truman’s come-from-behind 1948 victory and then Dwight D. Eisenhower’s dominant 1952 showing. Democrats quickly flipped the House back in the 1954 midterm, starting an uninterrupted 4-decade streak of Democrats holding the majority in the chamber.

That was the last time the House majority flipped in 2 consecutive elections (1952 and 1954). The House is competitive enough that we could see this happen again in 2022 and 2024. How Republicans in the House are able to govern — or unable to — will have some bearing on how the next election goes. Their first governing decision is picking a speaker — we’ll all be watching to see how they proceed later today.