| Dear Readers: This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, which features short updates on elections and politics.

— The Editors |

Are any deep blue Senate seats in danger for Democrats?

As Democrats attempt to defend their Senate majority, they hold 4 seats that both sides see as prime Republican targets: Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and New Hampshire.

Given Biden’s poor numbers and the usual problems the presidential party has in midterms, Republicans have a prime opportunity to flip 1 or more of these Democratic-held Senate seats. For instance, a couple of polls last week showed Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) slightly behind his likely opponent, former football star Herschel Walker (R).

Beyond these states, there has been some Republican activity worth noting in some of the dark blue states the Democrats are defending. In Washington state, veterans advocate and first-time candidate Tiffany Smiley (R) raised a bit over $900,000 last quarter in her bid to unseat Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA). In Connecticut, former state House Minority Leader Themis Klarides (R) switched from the governor’s race to the Senate race against Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), paving the way for businessman Bob Stefanowski (R) to seek a rematch against first-term Gov. Ned Lamont (D), who beat Stefanowski in a highly competitive 2018 race. Of course, a much bigger development for Republicans would be if popular Govs. Phil Scott (R-VT) or Larry Hogan (R-MD) jumped into Senate races in those states, but both incumbents have thus far declined to do so.

Realistically, though, do Republicans have any shot at these blue state Senate seats? Let’s see what recent midterm history tells us.

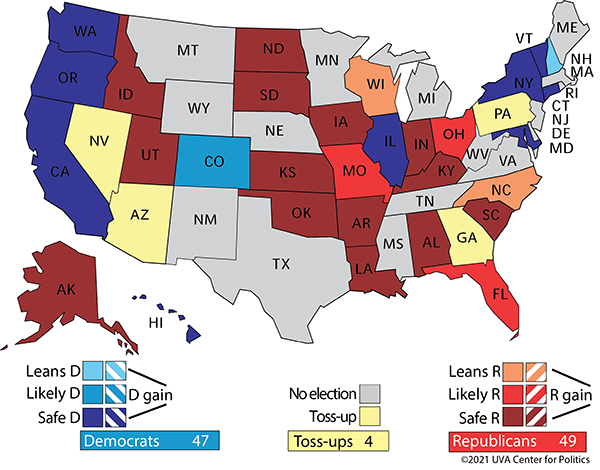

First of all, Map 1 shows our ratings for all 34 seats up for election this year.

Republicans are defending 20, while Democrats are defending 14.

Map 1: 2022 Crystal Ball Senate ratings

Table 1 shows Joe Biden’s margin in the states where Democrats are defending Senate seats this year (the states are sorted from smallest Biden margin to largest).

Table 1: Biden 2020 margin in Senate seats Democrats are defending

Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

The past 4 midterms — 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018 — all featured strong political environments for the non-presidential party (as midterms often do). Table 2 shows the Senate seats that the non-presidential party flipped in those 4 elections. The “change” column compares how the party that flipped the seat performed in the midterm Senate race compared to how that party performed in the previous cycle’s presidential race in that state. For instance, George W. Bush won Missouri by 7.2 points in 2004. Two years later, Claire McCaskill (D) unseated then-Sen. Jim Talent (R-MO) by 2.3 points. So that was a 9.5-point pro-Democratic swing when comparing the 2004 presidential race to the 2006 Senate race.

Table 2: Midterm Senate flips for non-presidential party, 2006-2018

Note: * indicates that an incumbent was defending the seat in the general election

Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

So, what stands out from Table 2? First of all, non-presidential party candidates are perfectly capable of running decently ahead of how their party performed in the state in the previous cycle’s presidential election. Note that in Table 1, Democrats are defending 3 very marginal Biden-won states in the Senate (Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada). It would take only a roughly 2.5-point decline in Democratic margin from the 2020 presidential margin to flip all 3 states (and less than that to just flip Arizona and Georgia). Democrats themselves improved from their previous presidential performance by more than that amount in the 2 seats they flipped in 2018, Arizona and Nevada.

It’s also pretty easy to find examples of a shift that would be enough to flip New Hampshire, which Biden won by a little under 7.5 points — although many of those come in the 2006 and 2010 cycles, an era in which Senate races were less tied to presidential partisanship.

Generally speaking, when a party flipped a Senate race in a midterm, that party performed better in the Senate race than the previous year’s presidential race. However, when there are exceptions (like Rhode Island in 2006 or Alaska in 2014), it was because there was a strong presidential party incumbent in place who ran ahead of presidential partisanship but still ended up losing. Some of what you can see in the midterm history here is the sorting out of Senate seats along the lines of presidential voting. That was a big development in 2014, when Republicans flipped 9 seats, only 2 of which were won by Barack Obama in 2012.

The biggest swing on this table — North Dakota from the 2008 presidential to the 2010 Senate race — came because of several factors. Barack Obama performed very well for a Democrat in the Dakotas in 2008, and popular Sen. Byron Dorgan (D-ND) retired, giving way to a vastly underfunded replacement Democratic candidate who was no match for popular sitting Gov. John Hoeven (R-ND). More broadly, Obama’s performance across the Midwest was outstanding in 2008 — including in his home state of Illinois — which made the pro-GOP swings in some of the Republicans’ 2010 Senate flips look particularly pronounced.

In the last 2 midterms — 2014 and 2018 – only 1 of the Senate seats that the non-presidential party flipped, Iowa, shifted in a margin large enough (14.1 points) to endanger the fifth-most competitive seat that the Democrats are defending this cycle (Colorado, at +13.5 points Biden). And there were extenuating circumstances in Iowa, where now-Sen. Joni Ernst (R-IA) pretty obviously ran a better race than then-Rep. Bruce Braley (D, IA-1). It’s also clear in hindsight that Ernst’s surprisingly large victory was a preview of Iowa’s broader turn toward Republicans later in the decade. Note that in 2014, when Cory Gardner (R-CO) won his single term in the Senate, his margin was a little more than 7 points better than Mitt Romney’s 2012 showing, which allowed him to narrowly win. Colorado has only gotten bluer, and Republicans do not have a candidate as proven as Gardner running this time. We rate Colorado as Likely Democratic.

In order to flip some of the states that are bluer than Colorado, like the aforementioned Connecticut or Washington (both of which Biden won by about 20 points and both of which are being defended by incumbents), Republicans would have to turn in an overperformance akin to that of now-Sen. Jon Tester’s (D-MT) showing in 2006 against then-Sen. Conrad Burns (R-MT), who was hurt by scandal and gaffes as well as the political environment. Additionally, Montana is less Republican down the ballot and is no stranger to electing Democratic senators: Connecticut and Washington have not elected a Republican senator since 1982 and 1994, respectively.

And as popular as Scott and Hogan are in Vermont and Maryland, they’d have to run more than 30 points better than Donald Trump’s 2020 margin to win their respective states.

This is all a long way of saying that while we could see Republicans getting closer than they usually get in states like Connecticut and Washington this cycle, actually flipping those states would be an awfully heavy lift, which is why we’re keeping them at Safe Democratic for now. And while we would have to reevaluate Maryland and Vermont in the unlikely event that one of those governors gets in, we don’t think we’d rate either as a Toss-up to start, even if polls suggested that we should.

Redistricting: As HI and SC enact maps, NY Dems release plan

Since our update last week, a couple of smaller states — Hawaii and South Carolina — have enacted new U.S. House maps, although the big event over the weekend was in New York, where legislative Democrats released their long-expected congressional gerrymander. The redistricting process also became a bit clearer in Pennsylvania, another larger state, where the task of overseeing the line drawing has fallen to the courts.

But we’ll start with the states that have passed maps. Hawaii’s commission shifted around only a few precincts on the state’s 2-district map. As has been the case since the 1970s — when the state began electing members from 2 separate districts — HI-1 is entirely confined to the island of Oahu (which contains Honolulu) while HI-2 contains the remainder of the archipelago. Biden carried the state by a 64%-34% margin in 2020, and both districts reflect that margin almost exactly. Barring an odd situation like the 2010 special election in HI-1 — where Republicans took the seat with a 39% plurality — these are 2 of the most secure Democratic seats in the country.

Political observers may have had some déjà vu watching South Carolina’s redistricting process unfold: despite total Republican control of government, negotiations between the 2 chambers were a little more prolonged than expected — this was the case after 2010. But last week, the state House acquiesced with a state Senate-sponsored plan, and Gov. Henry McMaster (R-SC) signed it.

Much of the wrangling between the chambers had to do with SC-1, a seat in suburban Charleston that Democrats snagged in 2018. Republicans recovered it in 2020. Under the new plan, Trump’s margin in the 1st District expands from 52%-46% to nearly 54%-45% — it is likely that ex-Rep. Joe Cunningham (D, SC-1) wouldn’t have won in 2018 if these lines were in place then. Republican Rep. Nancy Mace faces a credible challenger in Democratic physician Annie Andrews, although we’re starting the seat off as Safe Republican. Mace has not been a Trump favorite, so if at some point she loses a primary to a further right challenger, the district may be more in play. Regardless, Democrats would probably need another blue wave year to flip this seat.

SC-2, which includes the Columbia suburbs, is a possible longer-term target for Democrats — Trump’s 10.6% margin there was a bit worse than what he got statewide — but it is Safe Republican for 2022.

House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn’s SC-6 actually falls to under 50% Black by composition (the outgoing version is 52% Black, but had to pick up nearly 85,000 residents), but remains deep blue. Barring some type of court-induced action, Clyburn seems likely to remain the sole Democrat in the Palmetto State delegation.

Finally, on Sunday, Democrats were salivating as New York legislators unveiled their congressional proposal. While New York has an independent commission, it was expected that Democrats — who have control of the governorship and the legislature — would ultimately pass their own partisan plan.

Though the New York plan is not final, and may have to withstand legal scrutiny, it would potentially halve the number of Republicans in the state delegation: New York currently sends 8 Republicans to Congress, but only 4 districts on the new 26-seat map would have favored Trump in 2020.

Democrats’ plan also helps some of their own vulnerable members: Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney (D, NY-18), who occupies a conspicuous position as chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, holds a marginal seat in the Hudson Valley — Biden’s margin in the district would rise from 52%-47% to 53%-45%.

We will have more to say on the plan if it is signed into law, but House Democrats, who are looking at a potentially dismal national environment, may be bolstered by the New York map.