| Dear Readers: This is the eighth part of our multi-part series on congressional redistricting. Part One provided a national overview, Part Two covered several small-to-medium-sized states in the Greater South, Part Three looked at four larger states in the South, Part Four considered the West Coast and the Southwest, Part Five swept through a sampling of Great Plains and Heartland states, Part Six surveyed the electorally-critical Great Lakes region, and Part Seven finished the national tour in the Northeast. This week, we’ll conclude with some broader thoughts, though with several states already releasing draft maps, look for more redistricting-related content in the coming months.

— The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Over the past several weeks, we’ve analyzed redistricting all over the country.

— Overall, our House outlook remains unchanged after this analysis: There are a lot of reasons to like the Republicans’ chances of winning a majority next year.

— All of our 44 full redistricting previews for each state are reprinted below.

Wrapping up our redistricting series

Analyzing redistricting is a time-consuming and detail-oriented endeavor. As we were wrapping up our eight-part series looking at all 44 states that have more than one congressional district, and thus must draw new districts in advance of the 2022 election, we decided to count up all the words we wrote as part of this series. The total was close to 45,000 words, which is the length of a fairly short book. So we salute all of you who read or even skimmed everything we wrote.

As a way of wrapping up our preview, we thought we’d try a minimalist approach after using a maximalist one for the bulk of this series. Below, we’ve tried to sum up the redistricting state of play in every state… in a single sentence.

For those who may have missed part of the series, we also have reproduced all 44 state entries below. In the coming weeks and months, we’ll be analyzing the actual maps and also issuing race ratings for completed states.

There are six states — Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming — that have only one member of the House, and thus won’t need to redistrict. These states are all safe for the incumbent party for the foreseeable future, with the possible exception of Alaska, where Rep. Don Young (R, AK-AL), the Dean of the House, has had some close-ish races in recent years. And while Wyoming is arguably the most Republican state in the country, Rep. Liz Cheney (R, WY-AL) will clearly have spirited primary opposition given her criticism of Donald Trump, assuming she runs for reelection. Our initial 2022 ratings for these single-district states are Safe Democratic in Delaware and Vermont, Safe Republican in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, and Likely Republican in Alaska.

With that, let’s quickly summarize our outlook for the other states, and then we’ll offer a few concluding words.

Alabama: (6-1 R currently, no change in number of seats): Barring judicial intervention, Alabama should continue to elect six Republicans and one Democrat to the House.

Arizona (5-4 D, no change): Republicans are happier with the composition of the state’s independent redistricting commission than they were a decade ago, but it’s unclear how the maps will change in this growing state.

Arkansas (4-0 R, no change): Republicans rule the roost here and should continue to enjoy a monopoly in the delegation.

California (42-11 D, losing a seat): The state’s independent redistricting commission needs to eliminate a district, and Democratic-heavy Los Angeles County is the likeliest location of the eliminated district.

Colorado (4-3 D, adding a seat): A new independent commission has already released draft maps, which likely will help Democrats add the state’s new seat.

Connecticut (5-0 D, no change): Don’t expect many big changes.

Florida (16-11 R, adding a seat): Despite state constitutional prohibitions on gerrymandering, Florida Republicans likely will attempt an aggressive gerrymander anyway, and a conservative state Supreme Court may not intervene to stop them.

Georgia (8-6 R, no change): Republicans likely will be able to flip at least one seat through redistricting, though they also must be mindful of rapid demographic change in metro Atlanta that could eventually unwind their pending 2022 gerrymander.

Hawaii (2-0 D, no change): Yawn.

Idaho (2-0 R, no change): Also yawn.

Illinois (13-5 D, losing a seat): Democrats likely will attempt an aggressive gerrymander, with the goal of a durable 14-3 majority in the delegation.

Indiana (7-2 R, no change): Republicans will want to shore up Rep. Victoria Spartz (R, IN-5) in the northern Indianapolis suburbs.

Iowa (3-1 R, no change): The state is known for having a nonpartisan process, but Republicans have the power to pass a plan that would, at minimum, favor their three incumbents.

Kansas (3-1 R, no change): The main focus is on whether Republicans will imperil the delegation’s lone Democrat, Rep. Sharice Davids of KS-3 in the Kansas City area.

Kentucky (5-1 R, no change): Republicans could try to target Rep. John Yarmuth (D, KY-3), but many top Republicans don’t seem to have the desire to do that.

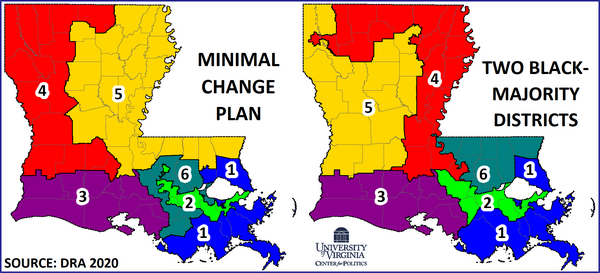

Louisiana (5-1 R, no change): Minimal changes seem likely, though Democrats may pressure Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) to fight for a second Black-majority seat — if he does, he may have to make his case in court.

Maine (2-0 D, no change): The rural 2nd District should get slightly bluer, but it seems poised to host a competitive race next year, regardless.

Maryland (7-1 D, no change): National Democrats would love an 8-0 plan, but state Democrats also could opt to just clean up the contorted lines on the current 7-1 map.

Massachusetts (9-0 D, no change): With all nine seats solidly blue, incumbent preferences will likely inform the changes.

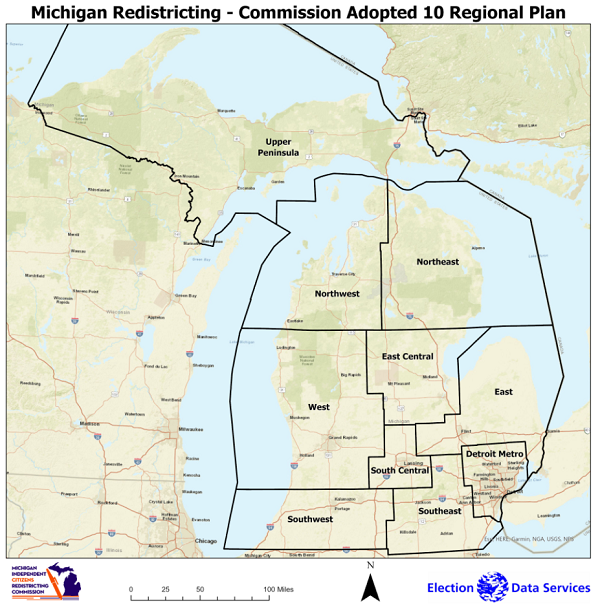

Michigan (7-7 tie, losing a seat): A new independent commission makes the state hard to handicap: Both parties probably will retain at least three or four firm seats, but the commission’s choices in populous Oakland County will be key.

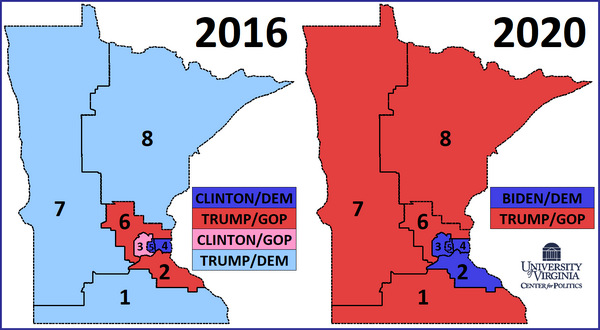

Minnesota (4-4 tie, no changes): As is usually the case in redistricting years, Minnesota has divided government, meaning the process could fall to courts.

Mississippi (3-1 R, no change): Look for Mississippi to retain three solidly GOP seats, as well as a single Black-majority Democratic seat.

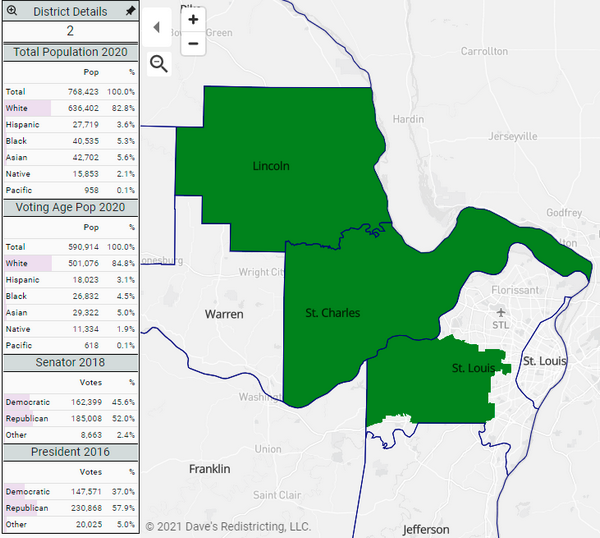

Missouri (6-2 R, no change): The overriding objective of Republicans, who control the process, will be to strengthen Rep. Ann Wagner (R, MO-2), though they may also consider going after Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D, MO-5).

Montana (1-0 R, gaining a seat): Democrats may be competitive in a light red western Montana-based seat, but the state should end up with two Trump-won districts.

Nebraska (3-0 R, no change): If a minimal change map is passed, Rep. Don Bacon (R, NE-2) should retain a Joe Biden-won seat, but he has considerable crossover appeal.

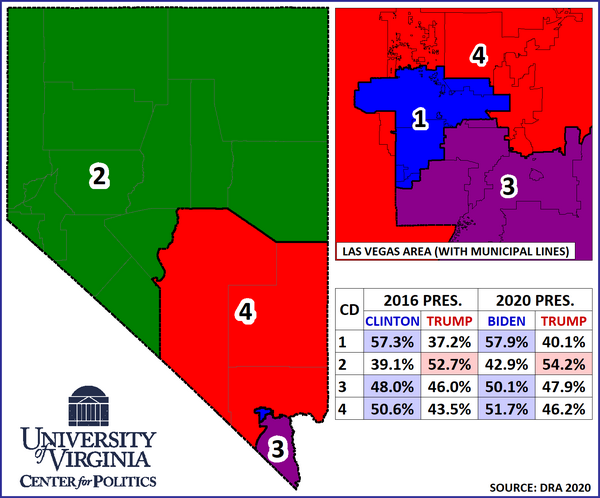

Nevada (3-1 D, no change): Democrats will want to bolster their somewhat shaky 3-1 edge in the delegation — they could unpack the Las Vegas-area NV-1 while leaving NV-2 as the sole red seat.

New Hampshire (2-0 D, no change): While it is hard to draw a Trump-won seat in the Granite State, Rep. Chris Pappas (D, NH-1) seems likely to get a lighter blue seat as a result of the Republican-controlled redistricting process.

New Jersey (10-2 D, no change): Democrats got their preferred tiebreaking member on the bipartisan commission that will draw the lines, but Republicans should still have some credible pickup targets when the dust settles.

New Mexico (2-1 D, no change): While the state recently passed an advisory commission, Democrats could ignore its recommendations to pass a 3-0 plan — but satisfying their incumbents may be tricky.

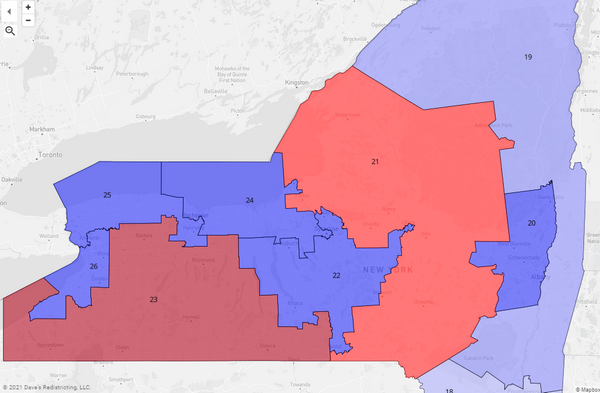

New York (19-8 D, losing a seat): The Empire State has a new commission system, but Democrats have the power to circumvent it and aim for a gerrymander that could give them as large as a 23-3 edge statewide.

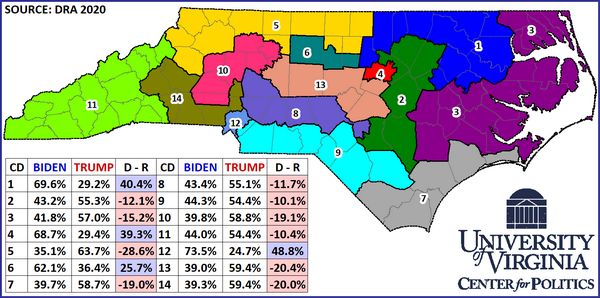

North Carolina (8-5 R, adding a seat): The new NC-14 could be drawn as a red-leaning seat, while the GOP could try to reclaim one — or both — of the seats they coughed up in a court-ordered redistricting last cycle.

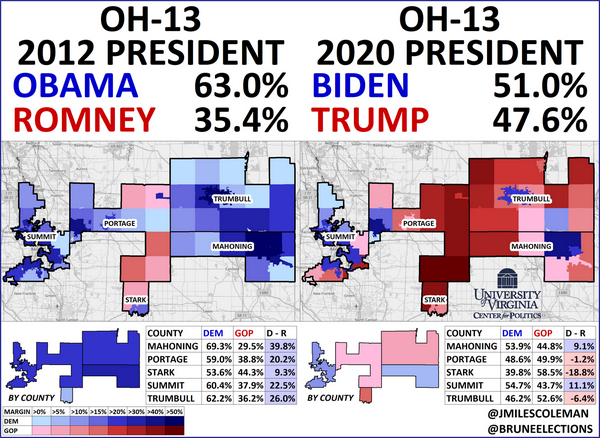

Ohio (12-4 R, losing a seat): The state’s new, less partisan redistricting system may — or may not — constrain Republican gerrymandering power.

Oklahoma (5-0 R, no change): With four solid seats, Republicans will want to ensure that Oklahoma City’s OK-5 — which Democrats won in 2018 but lost last year to now-Rep Stephanie Bice (R) — is less prone to flipping in the future.

Oregon (4-1 D, adding a seat): With Republicans having a seat at the table, it is possible that the state will add a GOP-leaning but still competitive seat.

Pennsylvania (9-9 tie, losing a seat): With divided government, the state Supreme Court could be drawing another map, which could eliminate a Republican seat but make one or more Democratic seats more Republican in the process.

Rhode Island (2-0 D, no change): The state somewhat surprisingly kept its second seat in reapportionment, which means Democrats were prevented from losing one of the state’s two safe Democratic seats.

South Carolina (6-1 R, no change): Palmetto State Republicans will focus on shoring up first-term Rep. Nancy Mace (R, SC-1), and they will be aided in doing so by population growth patterns.

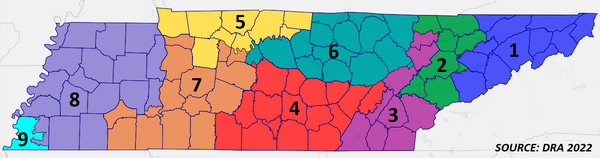

Tennessee (7-2 R, no change): Rep. Jim Cooper (D, TN-5) is in major danger of seeing his Nashville-based district dismantled, which wuld allow Republicans to win an 8-1 edge in the delegation.

Texas (23-13 R, adding two seats): At a minimum, Texas Republicans will try to grab the state’s two new seats through gerrymandering, and they very well could do even better than that.

Utah (4-0 R, no change): A new commission does not take the power from the state’s dominant Republicans, who likely will try to shore up first-term Rep. Burgess Owens (R, UT-4) in the state’s only truly competitive district.

Virginia (7-4 D, no change): Democrats are lamenting the creation of a new commission system, which could prevent the shoring up of swing-district Reps. Elaine Luria (D, VA-2) and Abigail Spanberger (D, VA-7) and might even make them more vulnerable to Republican challengers.

Washington (7-3 D, no change): A commission system that has developed a reputation for protecting incumbents will draw the lines.

West Virginia (3-0 R, losing a seat): One of the state’s three Republicans will not be returning to the House in 2023 because of the state’s loss of a seat.

Wisconsin (5-3 R, no change): Divided government could throw redistricting to the state Supreme Court, and without major changes the now-open WI-3 will remain one of the top GOP pickup opportunities in the nation.

Conclusion

So what does this all mean? Well, we don’t feel comfortable making hard-and-fast projections based on maps that have not yet been drawn, and while the redistricting process is important, the maps don’t always determine the winners in the most competitive districts. Also, even if we have guesses as to how states might re-draw the lines, those guesses can feature a combination of direct and indirect redistricting casualties. For instance, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court may draw the Pennsylvania map, which is currently split 9-9 between the two parties. The court might eliminate an underpopulated Republican-held district while also weakening Democrats in a couple of other districts, which could mean Republicans might come out of the state with an edge in the delegation even if two of their members are placed in the same, sprawling rural district.

Still, there is an overall, general assessment we can offer.

We’ve said before that the Republicans were favored to win the House majority next year, both because of redistricting and also because of the usual midterm trend that breaks against the party in the White House, among other factors. Following the completion of this redistricting preview, we have not changed our view on that.

We did our own back-of-the-envelope projections of the House and anticipated some aggressive (but not maximally aggressive) gerrymandering by both Republicans and Democrats, where applicable. We also assumed a somewhat neutral political environment, which very well may not end up being the case – in all likelihood, Joe Biden’s currently net-negative approval rating needs to rebound for there to be even a neutral environment next year as opposed to a Republican-leaning one.

Anyway, we got a GOP net gain of roughly a dozen seats, more than the five-seat improvement they need from the 2020 results to win the House majority. This is a deliberately modest outlook, and Republicans could easily blow past it next year, while there are also scenarios under which Democrats are able to minimize those GOP gains and perhaps even save their majority. But our default expectation has been, and remains, a Republican House takeover next year.

So now we’ll wait and see what the actual maps look like, which will inspire many more words (and maps and tables) to come.

Reprinted below are all 44 full state analyses.

ALABAMA

Number of seats: 7 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 6-1 R

Current party breakdown: 6-1 R

Most overpopulated district: AL-5 (Huntsville, Northern Alabama)

Most underpopulated district: AL-7 (Black Belt, Birmingham-Montgomery-Tuscaloosa)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

The 2012 Alabama map was perhaps one of the nation’s most understatedly durable gerrymanders. Going into the redistricting process, the Republicans — who had just won control of the state legislature for the first time since Reconstruction — aimed to lock in their gains from 2010. Though the Democrats were down to holding just one of the state’s seven seats, they had held — or made serious attempts at — three other districts during the last decade. Two Republican freshmen were strengthened: then-Rep. Martha Roby (R, AL-2), who had narrowly ousted a Democrat in 2010, saw several Black precincts in Montgomery removed from her Wiregrass-area district, while Rep. Mo Brooks (R, AL-5), up in northern Alabama, lost a few historically Yellow Dog counties (Lawrence and Colbert), and took in more reliably GOP Morgan County. Finally, Rep. Mike Rogers (R, AL-3), who was held to just a 7% win in 2008, relinquished most of his holdings in Montgomery County in favor of picking up heavily GOP St. Clair County.

As a result of the Republican map, and the state’s overall trends, 139 of the 140 congressional races that Alabama saw over the course of the decade ended up as double-digit blowouts, with the one exception being an odd case: in 2016, a Republican write-in candidate took 9% of the vote in AL-2, holding Roby to a 49%-41% win. In the one instance where the state did see a competitive statewide race, the districts behaved just as the GOP mappers would have liked: in the 2017 Senate special election, when now-former Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL) beat Republican Roy Moore, a horribly damaged candidate, Jones took nearly 80% in the Black-majority AL-7, but came up short in every other district — had the previous decade’s map been in place, Jones would have claimed two additional seats.

One dynamic that helped Republicans in 2012, which will probably aid them again, is that the state’s most underpopulated district is the heavily Democratic AL-7. While about three-quarters of the district’s population comes from a trio of urban counties (Jefferson, which contains the city of Birmingham, as well as Montgomery and Tuscaloosa), it includes much of the state’s portion of the Black Belt — and the rural counties there are losing population. So, to pick up population, it seems likely AL-7 will have to expand further into the Birmingham and Montgomery areas, which should help insulate Republicans in adjacent districts.

The state’s quickest-growing district is the northern AL-5, which is now open, as Brooks is running for Senate. Huntsville, the anchor of the district, may actually now be the largest city in the state — its government facilities, specifically the Redstone Arsenal, have drawn high-tech jobs to the area. A quick fix that Republicans may like would be transferring some Democratic precincts in Florence to the neighboring AL-4 — the 4th is now the reddest district in the country based on the 2020 presidential results, and can easily afford to take in bluer turf. Democrats would love for a court to force the drawing of a second majority-Black or Black-voter-influence district, but that does not strike us as particularly likely. Some projections prior to the release of the 2020 census reapportionment numbers suggested that Alabama was likelier than not going to lose a seat, but that did not come to pass; had that happened, Republicans would likely have lost a seat because the Voting Rights Act would have protected Democrats in AL-7.

So this is all to say that, given the population and partisan trends in Alabama, Republicans should have little trouble drawing a similar 6-1 map for the next decade.

ARIZONA

Number of seats: 9 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 5-4 D

Current party breakdown: 5-4 D

Most overpopulated district: AZ-5 (Chandler/Gilbert/Mesa)

Most underpopulated district: AZ-2 (Tucson)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

Arizona not gaining a 10th seat was one of the biggest surprises of the 2020 congressional reapportionment. In fact, 2020 marked the first census since the 1950 round that Arizona did not gain at least one seat in Congress — the state’s growth in recent decades has been especially robust, as its population has doubled in the last 30 years, going from 3.7 million residents in 1990 up to about 7.3 million today.

Even with that type of growth, the Arizona map will continue to feature nine congressional districts. While some states have adopted redistricting commissions fairly recently, Arizona’s was established to draw maps immediately after the 2000 census, as voters approved the creation of a commission via a referendum that year. But last decade, the legitimacy of the commission was tested. In 2012, Arizona Republicans were frustrated after the commission-drawn map elected a 5-4 Democratic congressional delegation, even as then-President Obama lost the state by nine points in his reelection bid. Legislative Republicans charged that the commission’s authority was unconstitutional, and took their case to the Supreme Court. But the high court ruled that voters could transfer jurisdiction over redistricting away from legislatures, so the Arizona commission was upheld. Republicans believed that last decade’s tiebreaking member overly helped the Democrats and unsuccessfully tried to have her removed from the commission. This time, the GOP seems happier with the tiebreaker.

Nestled in the southeastern corner of the state, AZ-2 is the only district that currently does not contain any of Maricopa County (home to Phoenix, as well as over 60% of the state’s residents) — it is also the most underpopulated district, and it will need to pick up about 75,000 residents. It seems likely that the district will simply pick up some communities near Tucson, or perhaps expand its holdings in the city itself. Assuming its configuration stays similar, longer-term trends suggest the district will stay Democratic: after Mitt Romney carried it by nearly three percentage points in 2012, President Biden did so by about 11 points.

After last decade’s remap was finalized, many Republican complaints centered on the redrawn AZ-1. This vast rural district includes both the Hopi and the Navajo nations, in the northeastern corner of the state, but for 2012, it dropped much of heavily GOP Yavapai County. Democrats captured the seat in 2008 with then-state Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick. Two years later, Kirkpatrick lost to Republican Paul Gosar by 13,583 votes — Gosar carried Yavapai County by just over 20,000 votes.

As an aside, Kirkpatrick has one of the most interesting career arcs of any current member. For 2012, Gosar moved over to the redrawn AZ-4 (now the most heavily GOP seat in the state), while Kirkpatrick reclaimed the swingier AZ-1. Kirkpatrick, impressively, held on in 2014, then ran unsuccessfully for Senate in 2016 against the late Sen. John McCain (R-AZ). She then moved to a new district herself, winning AZ-2 in 2018 and 2020. She is retiring this cycle.

Though AZ-1 narrowly supported the GOP presidential nominees in 2012 and 2016, Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D, AZ-1) has represented the district since Kirkpatrick vacated it, in 2016. Ironically, last year, as the district finally voted blue at the presidential level, O’Halleran had the closest race of his career — he was held to a three-point win. It would not be hard for the commission to make AZ-1 more Republican-leaning: it could simply take in more of Yavapai County, or reach further into Pinal County, a fast-growing county that has seen sprawl from the Phoenix area.

It seems unlikely that the commission will alter AZ-3, a Hispanic-majority seat held by Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D, AZ-3). The 3rd District forms a triangle, running from Tucson to Yuma, then up to Phoenix. Similarly, it’s hard to see major changes to Democratic Rep. Ruben Gallego’s AZ-7 — it is also heavily Hispanic by composition, but it is a much more compact seat centering on downtown Phoenix.

Elsewhere in Maricopa County, it is hard to game out exactly what the commission will do in the suburban Phoenix seats. Since the state isn’t adding or losing any seats, the commission could take a minimal change approach. In 2020, Democrats targeted Rep. Dave Schweikert (R) in AZ-6, a district that includes much of Scottsdale — he held on 52%-48%, so any similar seat could be swingy. On either side of AZ-6, Reps. Andy Biggs (R, AZ-5) and Debbie Lesko (R, AZ-8) both won by close to 20 points last year, and each would be favored under similar lines (Biggs has been mentioned as a potential statewide candidate in 2022, but any competent Republican could hold his seat).

If the commission prioritizes creating competitive seats, it may unpack AZ-9, giving its Democratic voters to adjacent districts. AZ-9, which sits east of Phoenix and includes communities like Tempe and Mesa, was created for 2012. Initially, it was a true bellwether seat, as it basically matched the national popular vote that year — but in 2020, Biden cleared 60% in the district. Now-Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) was the 9th District’s first representative — when she vacated it to run for Senate in 2018, then-Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton ran as a Democrat and held the seat by a 61%-39% margin. In fact, the only Republican to ever carry AZ-9 in a statewide race was the late Sen. McCain in his 2016 race against Kirkpatrick.

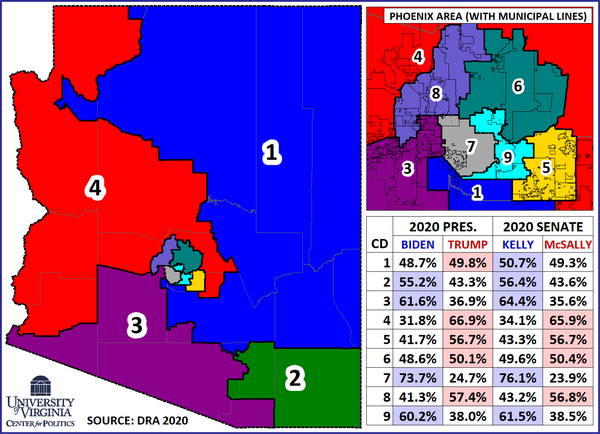

Map 1 shows an Arizona map with minimal changes, although the marginal AZ-1 flips from a narrow Biden-won seat to a narrow Trump-won seat, while AZ-6 takes in all of Scottsdale and gets slightly more competitive (but is still a Trump-won seat).

Map 1: Hypothetical Arizona map with minimal changes

Realistically, Arizona’s next congressional map could lead to anything from a Democratic gain of one seat to a GOP gain of two seats.

ARKANSAS

Number of seats: 4 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 4-0 R

Current party breakdown: 4-0 R

Most overpopulated district: AR-3 (Northwest Arkansas)

Most underpopulated district: AR-4 (Southern Arkansas)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Democrats

Of all the current congressional maps in place, Arkansas’ is probably the closest thing we have to a dummymander. For the first decade of the 2000s, Democrats held three of Arkansas’ four House seats, with the sole Republican, now-Sen. John Boozman (R-AR), representing the ancestrally GOP northwestern corner of the state. Then, ahead of the 2010 election cycle, two entrenched Democrats announced their retirement — in what turned out to be banner GOP year, those seats went on to flip. The good news for Democrats that year was that their third member, then-Rep. Mike Ross (D, AR-4) was not a top GOP target, and, helped by then-Gov. Mike Beebe’s (D-AR) popularity, they kept the legislative trifecta.

As legislative Democrats unveiled drafts of congressional plans in 2011, it was clear that they intended to preserve the basic contours of the existing map, with the goal of winning back a 3-1 advantage in the delegation. The problem, though, was that by then, a pro-Republican trend was obvious, so such a split would likely be unsustainable: in 2008, John McCain improved 10% over George W. Bush’s 2004 showing in Arkansas, with many rural counties shifting 20% or more to McCain. Democrats could have linked Little Rock to some heavily Black counties on the Mississippi Delta, which would have given them one reasonably firm district — with Black residents making up just 16% of the state population, a majority-minority seat is not required in Arkansas. When redrawing AR-4, Democrats deferred to the wishes of Ross, but, in something of an about-face, Ross ended up announcing his retirement.

Democrats ended up passing a plan where all four districts would have still given McCain easy majorities. If the political fault lines of the early 2000s still shaped voting habits, Arkansas would likely still have three Blue Dogs and one Republican in Congress. Instead, the state continued its rightward trek in 2012: The three incumbent Republicans were reelected, and, without Ross’ incumbency, AR-4 flipped red. Republicans also gained control of the state legislature that year, and have since increased their majorities. So now, holding the pen themselves, Arkansas Republicans are in a curious position: given their monopoly on the delegation, preserving something like the current Democratic-drawn map would probably suit them just fine.

The state’s fastest-growing district is AR-3 (where Wal-Mart is headquartered), while Little Rock’s AR-2 also saw growth over the past decade. The two primarily rural districts, AR-1 and AR-4, will have to expand. The shifting border between districts 3 and 4 sums up the state’s population trends well: in 1970, AR-3 stopped just short of the Louisiana border to the south — as the slow-growing 4th has expanded over the past decades, it now comes north, close to the Missouri line.

National Democrats were not the only group frustrated by Arkansas redistricting in 2011 — to the chagrin of political analysts, the legislature departed from tradition in that they split several counties between districts (election breakdowns for whole-county districts are easier to tabulate). Iowa and West Virginia are now the only two states with more than one district to feature whole county districts.

CALIFORNIA

Number of seats: 52 (down 1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 38-15 D

Current party breakdown: 42-11 D

Most overpopulated district: CA-45 (Orange County)

Most underpopulated district: CA-40 (East Los Angeles area)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

The U.S. House of Representatives reached its current-sized voting membership of 435 after the 1910 census, and it has had the same-sized membership ever since, with the exception of a temporary expansion to 437 to account for Alaska and Hawaii becoming states in the late 1950s.

In that initial 435-seat apportionment for the 1910s, California had 11 House members — tied with Iowa, Kentucky, and Wisconsin. The Golden State now has nearly five times that number of members (53), although the state’s explosive growth has slowed in recent years. The state did not add any seats in the 2010 reapportionment round, which was the first time it failed to add a seat following a decennial census.

This most recent reapportionment represented a new, dubious first for California — the state is actually losing a seat, going from 53 to 52, though it still has by far the biggest House delegation (Texas will be second at 38 seats).

The loss of a seat will force California’s independent redistricting commission to chop a district. Beyond that, it’s unclear how much the commission, which is in charge for the second time after voters created it in 2010, will tweak the lines.

The commission, which by law cannot take partisan data or incumbent residence into account, dramatically changed the state’s map a decade ago. That new map put 27 incumbents into 13 districts and created 14 with no incumbent; seven incumbents retired, and another seven lost either to members of their own party or members of the other party (California uses a top-two election system, in which the top two finishers in an all-party first round of voting advance to the November general election). The commission injected some competitiveness into a state that had hardly any of it under a Democratic-drawn incumbent protection map in place for the 2000s: Just a single seat switched hands that entire decade, as Democrats started the decade with a 33-20 edge that became a 34-19 advantage. Democrats immediately netted four seats in the 2012 election, and they were up to a lopsided 46-7 edge by the 2018 election. Republicans recovered some of those seats in 2020, clawing back four Biden-carried districts. Four of the nine Biden-won seats held by Republicans are in California, including the only three that Biden won by double-digits: Reps. Mike Garcia (R, CA-25), Young Kim (R, CA-39), and David Valadao (R, CA-21) all hold districts that Biden carried by about 10 points apiece. The fourth Biden-district California Republican, Rep. Michelle Steel (R, CA-48), holds a much more marginal seat (Biden won it by just 1.5 points). So one of the big questions about the commission is whether the commission will merely tweak the last decade’s map, given that it was already drawn by a commission as opposed to legislators, or whether the members will take a wrecking ball to the existing map, much like the commission did a decade ago. This question is unanswerable at this point (at least from our perspective).

California was once known for hard-edged gerrymanders. Congressional scholar David Mayhew has noted that a California Republican gerrymander in advance of the 1952 election (along with one in New York) contributed greatly to the Republicans winning a slim House majority in that election, which was one of only two House majorities the Republicans won in a more than six-decade stretch from the early 1930s to early 1990s (the other came in 1946). More recently, California Democratic power broker Rep. Phil Burton crafted a strong gerrymander after the 1980 census, pushing a 22-21 Democratic delegation to a 28-17 edge. Voters threw out the map in a 1982 statewide ballot issue, but Burton crafted another, similar gerrymander that outgoing Gov. Jerry Brown (D-CA) — then serving his first eight-year stint as governor — signed right before leaving office. If Democrats still retained gerrymandering power in California — and they would have it even if Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) is ousted in a recall next month because Democrats hold veto-proof state legislative majorities — they likely could squeeze several more seats out of the state by hurting some or all of the Biden-district Republicans and also potentially going after at least one of two prominent Central Valley Republicans: House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-23) and Rep. Devin Nunes (R, CA-22), the former chairman of the Intelligence Committee.

But Democrats do not have that power. Rather, the commission will be drawing the lines.

Now, it is fair to wonder whether Democrats will end up with something of a de facto edge on the commission. A decade ago, Democrats gained advantages in the process through out-organizing Republicans, as ProPublica noted at the time. Additionally, California is an overwhelmingly Democratic state, so even on a commission with five Democrats, five Republicans, and four members not affiliated with either party, one might expect the commission to lean Democratic to some extent, argues independent California pollster Adam Probolsky: “We have a progressive state. So even though the commission is mandated to have No Party Preference voters, remember, independent voters look and think just like their neighbors — they just don’t have loyalty to a party. So those independents are going to lean progressive.”

All that said, it would also be unfair to describe the last decade’s map as a Democratic gerrymander. Rather, it was a map that created a number of competitive seats that Democrats were able to capture, and it also created a number of safe Republican suburban seats in Southern California that became much less Republican over the course of the decade, to the point where Democrats were able to win several of them. For instance, Joe Biden did 15 points better than Barack Obama did in 2012 in both San Diego and Orange counties, which are the second and third-largest sources of votes in the state and where Democrats flipped several House seats last decade. A lot of that is realignment, not gerrymandering.

One thing that does stand out in the state’s demographics is that many districts in the Los Angeles area are underpopulated. Scott Lay, who produces The Nooner newsletter on California state politics, suggests that one possibility is that an East Los Angeles district may be eliminated, with the districts held by Reps. Grace Napolitano (D, CA-32) and Lucille Roybal-Allard (D, CA-40) as possibilities (both are in their 80s, so either or both could retire). One other possibility is that Rep. Karen Bass’ (D, CA-37) district west of downtown could be eliminated if she decides to run for mayor of Los Angeles, as has been recently rumored — that would be a way to effectively protect all the other incumbents (readers will remember that Bass was one of Joe Biden’s reported vice presidential options). Darry Sragow, publisher of the California Target Book, recently noted that LA County contains all or part of 14 congressional districts, and that the ideal population size for California districts this decade will be about 760,000 people. Combined, the 14 LA County districts are currently about 575,000 people short of that target, meaning that “It is almost certain that the one seat California must give up will come from there.” (Although, remember, we’re working off census estimates, not the actual census numbers, which are coming out later today.)

Democrats would surely prefer the eliminated district come from elsewhere in the state, with the Central Valley as a candidate.

Assuming a Democratic LA County seat is cut, perhaps Democrats can make up for that by beating one or more of the Biden-district Republicans — Garcia seems the most vulnerable to us, in part because of a conservative voting record (he backed both objections to the Electoral College certification in January) — or by getting positive district alterations elsewhere. That said, the commission is difficult to handicap, so we’re just going to have to wait and see.

COLORADO

Number of seats: 8 (+1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 4-3 R

Current party breakdown: 4-3 D

Most overpopulated district: CO-4 (Eastern Colorado)

Most underpopulated district: CO-3 (Western Slope/Pueblo)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Split

Colorado is one of the states where Democrats are kicking themselves for getting behind an independent/nonpartisan redistricting process last decade. Because Democrats now control state government, they could have gerrymandered the state, grabbing the state’s new, eighth seat and otherwise working to expand their current 4-3 edge in the delegation. But Colorado has a commission now, and it is really the only state so far where there’s already a working draft of the map. We analyzed this map in great detail when it was released, so for those who want to know more about the Colorado details, just look back at that piece. This map would, in most years, result in a 5-3 Democratic delegation. However, it will at the very least have to be tweaked slightly, because the map was drawn based on census estimates, not the actual census numbers. As political scientist Michael McDonald noted, the map draft likely has too much population deviation among districts to pass judicial muster.

We’ll continue to follow developments in Colorado, but let’s move on to other states that don’t have draft maps already.

CONNECTICUT

Number of seats: 5 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 5-0 D

Current party breakdown: 5-0 D

Most overpopulated district: CT-4 (Southwest Connecticut)

Most underpopulated district: CT-2 (Eastern Connecticut)

Who controls redistricting: Split

2012 control: Split

Connecticut is one of several states across the nation that used to feature strong competition at the U.S. House level but didn’t have much action last decade. Democrats won all five seats in all five election years last decade, and that was on a congressional map that was not gerrymandered to produce such an outcome.

A big reason for Connecticut’s transition from congressional battleground to Democratic bastion has been the long erosion of Republican strength in Fairfield County, the affluent, highly-educated part of the state that is closest to New York City and is the largest source of votes in the state. In 1996, Fairfield voted Democratic for president for just the second time since World War II (1964 was the other exception, as it so often was for historically Republican places in the North). By 2020, Fairfield was up to a 27-point margin for Joe Biden, the biggest margin it had given any Democrat for president possibly ever, or at least since at least the early 1880s (that’s as far back as Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections goes).

Former Rep. Chris Shays, the last Republican to win an election to the congressional district that covers Fairfield County, CT-4, is an exemplar of the moderate Republicanism that used to predominate in parts of the region. Elected in a 1987 special election, he first ran for reelection in 1988 — he claimed 72% while, up the ballot, George H. W. Bush took 57% in CT-4. Shays held on for three decades and was not seriously challenged until George W. Bush was in the White House. Finally, in 2008, as Barack Obama carried CT-4 by 20 points, Shays came up four points short against now-Rep. Jim Himes (D, CT-4).

A dozen years later, CT-4 was Biden’s best district in the state. Some of the Republican tradition in this part of the state still endures: Republicans recently won a special election for a state Senate seat that covers Greenwich and the New York border that voted heavily for Biden. However, state-level races in the district are typically much closer.

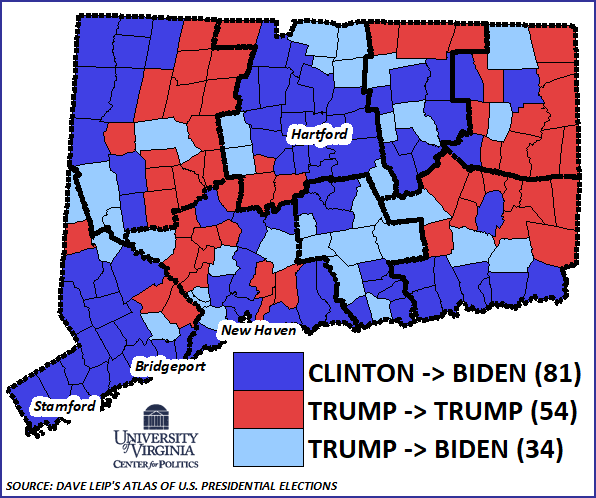

Some other parts of Connecticut flirted with Donald Trump in 2016 — he came within three points of winning Eastern Connecticut’s CT-2 and within about four of winning Northwest Connecticut’s CT-5, which was the state’s most competitive district at the U.S. House level in the 2010s. But, as it was in nearly every other congressional district in New England in 2020, Biden did better than Hillary Clinton, and he carried all five congressional districts in Connecticut by double digits. As Map 2 shows, in addition to holding all five congressional districts, Biden picked up almost three dozen towns that supported Donald Trump in 2016.

Map 2: Connecticut town loyalty, 2016-2020

The Nutmeg State has what amounts to a bipartisan redistricting process because Democrats lack the two-thirds state legislative majorities they need to draw the maps on their own. The two western seats, CT-4 and CT-5, are overpopulated to some degree, while the other three are underpopulated, though only CT-2 is significantly so. Courts could end up getting involved, as they did a decade ago when minimal changes were made to the map.

The bottom line in Connecticut is that under optimal circumstances, Republicans might be able to compete for one or more of its districts this decade. But if they do, redistricting likely will not have been a major contributor to that happening.

FLORIDA

Number of seats: 28 (up 1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 17-10 R

Current party breakdown: 16-11 R

Most overpopulated district: FL-9 (Central Florida)

Most underpopulated district: FL-13 (Pinellas County)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

In Florida, the coming redistricting process should bring no shortage of heartache for Democrats, but one of their most critical letdowns occurred almost three years ago: the winner of the 2018 gubernatorial race would get the opportunity to fill three seats on the state Supreme Court, as three Democratic-appointed justices were set to retire (judges on that court face a mandatory retirement age). In 2015, the state Supreme Court forced changes to the state’s Republican-drawn congressional map. The new map precipitated several Democrats pick-ups in the 2016 and 2018 cycles.

Despite trailing in most polls, and running in an unfavorable national environment, then-Rep. Ron DeSantis (R, FL-6) upset then-Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum (D) to keep the governor’s mansion in Republican hands. DeSantis filled the three positions, and the Florida Supreme Court is now one of the most conservative state courts in the country. With a new jurisprudence dominating the court, Democrats will find a less sympathetic audience for any redistricting challenges, though Republican legislators may not want to get too creative for their own good. Republican mappers may also be limited by the Fair Districts Amendment, a ballot measure that passed in 2010 and was meant to encourage compact and fair districts (but which Democrats are fearful that this court effectively will not enforce after the more liberal version of the court used it against GOP gerrymanders last decade).

With all this out of the way, let’s consider where things stand now, and what’s likely to change.

After the 2014 election, Republicans retained a 17-10 edge in the state’s delegation. But by the end of 2018, with a new map and a favorable midterm environment, Democrats had clawed within one seat of majority in the delegation, which became 14-13 Republican. Then, in 2020, as former President Donald Trump carried Florida by more than three percentage points — a comfortable margin, by state standards — he helped Republicans regain two seats in the Miami area, bringing their advantage back up to 16-11. The delegation will grow by one member at the start of the next Congress, although most observers expected it to gain two — Florida has added members since the 1940 census, when it was the least populous state in the South. It is now the nation’s third most populous state, trailing only California and Texas.

The most underpopulated district in the state in the panhandle-based FL-2, held by Republican Rep. Neal Dunn. The 2nd District, which is now mostly rural, traditionally included the city of Tallahassee. But with the 2015 remap, most of the 2nd’s holdings in the city were given to the newly drawn FL-5, which was intended to be a majority-nonwhite seat. While Rep. Al Lawson (D, FL-5) hails from the state’s capital area and represented in the legislature for years before his 2016 election to congress, a greater portion of the district actually comes from Jacksonville (it includes most of the city’s Black precincts). While some Republicans have maintained that the current iteration of FL-5 is not protected by the Voting Rights Act — by composition, it is less than 50% Black — Nicholas Warren of the Florida ACLU, argues that major changes won’t be in store for the district. We will just have to wait and see how Republicans deal with this district, and what legal fallout may ensue.

Moving south to the Orlando area, Democrats hold three seats, but seem likely to come out of redistricting with only two. FL-10, which is split roughly evenly among whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, was a seat created for 2015, and seems unlikely to change — as it usually gives Democrats over 60% of the vote, it acts as a vote sink in the area. Just to the south, the most populous district in the state is Rep. Darren Soto’s (D) FL-9, which needs to drop a whopping 165,000 residents. Whites and Hispanics each account for roughly 40% of the 9th’s population, though the latter group’s growth has been especially rapid. Given its minority population, Republicans may also steer clear of drastically reshaping FL-9 — it currently has a mild Democratic lean, but its redder holdings could be transferred out to shore up adjacent GOP seats.

North of Orlando, Republicans will likely target Rep. Stephanie Murphy’s (D, FL-7) district — though it contains some of Orlando proper, suburban Seminole County makes up the majority of FL-7. Unlike districts 9 and 10, the 7th has a white majority. Though the trends for Republicans in Seminole County have not been good (it was a Trump-to-Biden county), legislators could make it redder by giving it parts of working-class Volusia County, or rural precincts of Lake County. If FL-7 is heavily altered, Murphy, who is a leader in the moderate Blue Dog Coalition, may be able to run in a new version of FL-10, as Rep. Val Demings (D, FL-10) is running for Senate (though other credible Democratic candidates have already announced bids for the open seat).

Over in the Tampa Bay area, FL-13, which takes up three-quarters of Pinellas County, is another Blue Dog district that Republicans will have their eye on. Former Gov. Charlie Crist — who has, under three partisan labels, been a fixture in state politics for the last quarter-century — won this seat in 2016, but is now running for his old job. Before 2016, the legislature grouped most of the heavily Black precincts in St. Petersburg, Crist’s hometown, into Rep. Kathy Castor’s safely blue FL-14, which was focused on downtown Tampa (both parts of the district touched Tampa Bay, so the seat was contiguous). When the entirety of St. Petersburg was put back into FL-13, Crist ran and beat then-Rep. David Jolly (R) 52%-48% — those precincts were decisive.

With a friendly court, Republicans may try to put parts of St. Petersburg back into FL-14, though Democrats would probably cite the Fair Districts Amendment and sue. If Republicans wanted to go a less risky route, FL-13 is one of the few districts in the state that needs to gain population — they could simply add some redder Pinellas County precincts that are currently in FL-12. This district is competitive enough already that a Republican might be able to win it as its currently drawn, and Republicans may very well attempt to make it redder.

Finally, in south Florida, Republicans will probably be more interested in shoring up their current members than targeting Democrats. In 2020, three Cuban-American Republicans were elected to represent the Miami area: veteran Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R, FL-25) was unopposed for a 10th term, while now-Reps. Carlos Gimenez (R, FL-26) and Maria Elvira Salazar (R, FL-27) ousted Democratic incumbents who were first elected in 2018. Salazar is the only one of the trio who holds a Biden seat, though the president’s three-point margin in her district was down considerably from Hillary Clinton’s 20% margin from 2016. Republicans may remove parts of Miami Beach, which has a sizeable white liberal bloc, and give Salazar more ethnically Cuban precincts that are currently in Diaz-Balart’s seat. Gimenez may also want some help — though Trump carried his FL-26 by six points, it gave Clinton 57%.

If Trump’s numbers with Cubans represent a new normal, the GOP’s Miami-area incumbents should have little to fear. But Republican legislators would be wise to draw the lines with the understanding that this may not be the case.

Ultimately, Florida, like the other states mentioned here, is a state where Republicans likely will go as far as courts let them — or as far as they think courts will let them.

GEORGIA

Number of seats: 14 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 9-5 R

Current party breakdown: 8-6 R

Most overpopulated district: GA-7 (Greater Atlanta)

Most underpopulated district: GA-2 (Southwest Georgia)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

Georgia has been at the forefront of national politics over the last year. After hosting a razor-thin presidential contest and two blockbuster Senate runoff elections, the Peach State will once again find itself in the national spotlight when maps are redrawn later this year.

Though Democrats have found success in recent statewide elections, Republicans will be overseeing the mapmaking process because they still have majorities in both chambers of the state legislature and hold the governorship. With that trifecta, Republicans will face a tough balancing act: they will want to stymie Democratic gains in the Atlanta area but also protect their own incumbents — all while keeping the Voting Rights Act in mind.

To understand the daunting task that Georgia Republicans face, we must take a trip back in time to the early 2000s. Back then, Democrats had dominated state government since Reconstruction, but they faced an increasingly competitive GOP. Republicans were beginning to post impressive numbers in the state’s rural areas and cut into the Democrats’ state legislative majorities.

Democrats, seeing the writing on the wall, concocted egregious congressional and state legislative gerrymanders to preserve their dwindling grip on power.

The congressional map was certainly not easy on the eyes. The 2002 Almanac of American Politics noted that the map must be “admired for its creativity.” The state was awarded two new seats in the 2000 census, and, not coincidentally, both were drawn to favor Democrats. Still, the Almanac authors warned that the map may not last the entire decade, citing not only Republicans’ rise to power but several federal lawsuits challenging the legality of the maps. “This work of art may not endure,” the Almanac noted.

Sure enough, they were right. Courts threw out the Democrats’ state legislative maps, paving the way for Republicans to grab control of state government for the first time since Reconstruction. One of their first orders of business was redrawing the congressional map in a rare mid-decade redistricting session. The new map was much more compact and split fewer counties than its predecessor. Republicans also attempted to make more life more difficult for then-Reps. John Barrow (D, GA-12) and Jim Marshall (D, GA-8), two white Democrats with moderate voting records. Despite facing tougher constituencies, both Democrats were narrowly reelected in 2006’s broader Democratic wave.

In 2010, Rep. Sanford Bishop (D, GA-2), in the southwest, faced a surprisingly close race — so close that some news networks called it for his Republican opponent on Election Night. Elsewhere, Marshall lost reelection to now-Rep. Austin Scott (R, GA-8), but Barrow was comfortably reelected.

In the 2011 redistricting session, Republicans decided to make a tradeoff in order to protect Scott: Bibb County, which includes Macon, was the anchor of Scott’s district. GOP mapmakers decided to cede Bibb to Bishop in exchange for adding more rural counties to the 8th — importantly, as we’ll see later, this pushed the Black population share in GA-2 to over 50%. They also had their sights set on Barrow once again: they removed Savannah from his district and added more rural counties such as Coffee and Jeff Davis. When Barrow lost in 2014, he was the only remaining white Democrat in the Deep South — with his loss, the map produced its intended 10-4 Republican split.

This brings us to the upcoming redistricting process. Recent Democratic gains in the metro Atlanta suburbs have shifted the delegation from 10-4 to 8-6 Republican. In the 6th District, Rep. Lucy McBath (D) pulled off one of the biggest upsets of the 2018 midterms when she ousted Rep. Karen Handel (R), who had just won a high-dollar special election for this suburban district the previous year. The 6th also saw one of the largest swings from Barack Obama in 2012 to Joe Biden in 2020 of any district in the nation, going from Obama -23 to Biden+11. Handel waged a rematch in 2020, which McBath won comfortably.

In the 7th District, which includes most of rapidly diversifying Gwinnett County, now-Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux (D) came within 500 votes of ousting Rep. Rob Woodall (R) in what was the single closest House race of the entire 2018 campaign. Woodall decided against running for reelection in 2020, and Bourdeaux narrowly defeated emergency room physician Rich McCormick (R) in the general election, making her the only Democrat to flip a competitive Republican-held district in 2020.

Republicans are going to have to address their recent decline across the metro Atlanta suburbs, where they still have plenty of room to fall. No one knows what the map will end up looking like, but the general consensus seems to be that Republicans will attempt to combine the bluest parts of the 6th and 7th districts into one safely Democratic vote sink, in exchange for creating a new solidly Republican seat in rural and exurban northeast Georgia.

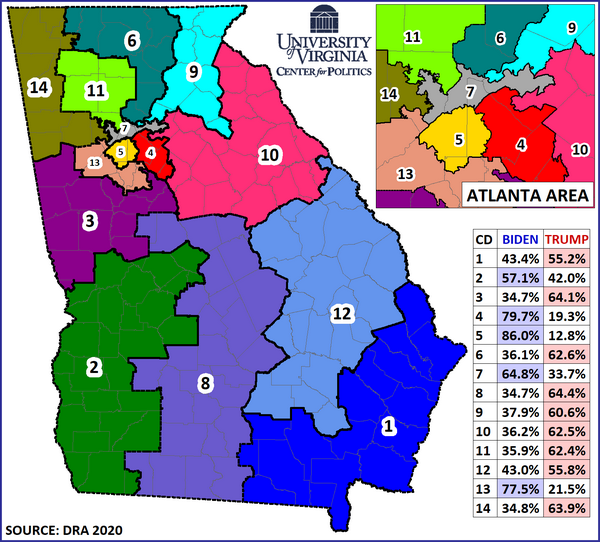

On Map 3, GA-7, a checkmark-shaped district arching across the Atlanta metro, would have given Biden a 30-point margin, while the much redder 6th District is stretched up to the northern border.

Map 3: Hypothetical 9-5 Republican Georgia gerrymander

The result of Map 3 would very likely be a Georgia delegation with nine Republicans and five Democrats. If GOP legislators try to redraw a Democratic-held seat to elect a Republican (GA-6, in this case), some of their own members, especially Reps. Andrew Clyde (R, GA-9) and Marjorie Taylor Greene (R, GA-14), would have to be team players: currently, both of their seats gave Trump about 75% of the vote, but are knocked down to under 65% Trump in Map 3. At the same time, Republicans would want to strengthen Rep. Barry Loudermilk (R, GA-11) — over the last decade, his district has crept down from 67% Romney in 2012 to 57% for Trump. On Map 3, GA-11 drops some of its closer-in parts of the Atlanta metro, and Trump’s share climbs back to 63%.

So if Republicans spread themselves out efficiently, most of their districts would end up being between 60% and 65% Trump — this is the case for seven of their nine seats on Map 3. Districts 1 and 12 are each closer to 55% Trump, but both are racially polarized and outside of their urban centers (Savannah and Augusta, respectively), Democratic support drops off steeply.

GA-7’s unique demographic trajectory may be one reason why Republicans may preserve it as a Democratic-leaning seat: it was originally drawn to be about 50% white but is now firmly a majority-nonwhite seat, so big changes could be seen as a violation of the Voting Rights Act by Democratic redistricting lawyers. Still, a judge may also note that Section 2 of the VRA mandates that some districts be drawn so that certain minority groups can elect candidates of their choice. Though the 7th District is now majority-minority, Bourdeaux herself is white, and the district also includes a mix of different types of voters of color (the district is roughly two-fifths white, a fifth Black, a fifth Hispanic, and a sixth Asian). We asked Charles Bullock, a redistricting expert at the University of Georgia who recently released a second edition of his excellent book, Redistricting: The Most Political Activity in America, about the 7th District. He noted that plaintiffs in a lawsuit based on the VRA’s Section 2 would face the challenge of showing that members of the three non-Hispanic white ethnic groups vote alike.

Some Republicans have also suggested that Bishop’s GA-2 might be at risk — the version on Map 3 gave Biden a not-overwhelming 57%, and it could easily be made more Republican. Carving out a redder district in southwest Georgia may seem enticing for the GOP, but a move like this could be seen as a violation of the Voting Rights Act. Unlike the 7th, the 2nd was intended to be a majority-minority district (remember, Republicans did this on purpose a decade ago in order to shore up the then-newly-elected Scott next door in GA-8). Black voters in the 2nd may feel disenfranchised if they are unable to have appropriate representation in Congress. Plus, it’s not guaranteed that a more competitive district in Southwest Georgia would be completely unwinnable for Bishop. His moderate stances on abortion and gun rights have played well with rural white voters over the years. And while we may live in era where down-ticket races are becoming increasingly tied to presidential races, Bishop maintains a respectable amount of crossover support. Bullock agreed that the district might be redrawn in such a way that Bishop could hold it, but perhaps not another Democrat if Bishop retired at some point this decade (Bishop is 74).

To make a long story short, Republicans are now facing the same predicament that Democrats faced two decades ago. Their majorities in the state legislature are getting smaller, the minority party has been surprisingly successful in recent statewide elections, and they are facing a grim outlook in areas of the state where they once dominated. Republicans are aware that redistricting could be their last chance to forestall new Democratic gains in state government.

HAWAII

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-0 D

Current party breakdown: 2-0 D

Most overpopulated district: HI-1 (Honolulu)

Most underpopulated district: HI-2 (Half of Oahu/remainder of islands in state)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

One could make a case that Hawaii is trending Republican: Barack Obama won the state of his birth by 45 points in 2008, and Joe Biden won it by just 29 in 2020. But it would not be a very good case, particularly because if you started in 2004, when George W. Bush came within nine points of carrying the Aloha State, you could argue the opposite.

Only two Republicans have ever won House elections in Hawaii: Pat Saiki won two terms in the late 1980s, and Charles Djou won a flukish, all-party special election in 2010, but lost the regular election later that year.

The state’s bipartisan redistricting commission will have to make some slight adjustments to account for population (the Honolulu-based 1st District will have to shed a little population to HI-2, which covers the rest of the state), but we otherwise wouldn’t expect much to happen here. Biden won each district by almost identical margins (a shade under 30 points apiece), so they are politically similar. Democrats are so dominant in Hawaii at the state level that Republicans only hold one seat in the 25-member state Senate.

IDAHO

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-0 R

Current party breakdown: 2-0 R

Most overpopulated district: ID-1 (Western Idaho)

Most underpopulated district: ID-2 (Eastern Idaho)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

Even though Idaho is one of the most Republican states in the Union, Democrats will have a seat at the table in redistricting thanks to the state’s commission system. The commission consists of three Republicans and three Democrats.

The commissioners will have to shift population from the growing 1st District, which contains the state’s distinctive northern panhandle, to the slower-growing 2nd District. The current plan splits Ada County, home to a bit more than a quarter of the state’s population and the state’s capital, Boise. Joe Biden came within four points of carrying the county — the closest any Democrat has come since World War II. But even a radically-remade Idaho congressional map that united Ada County still would need to add considerably more population, and the county is surrounded by considerably redder counties. In any event, we wouldn’t expect the lines to change much, and both districts are heavily Republican: ID-1 voted for Donald Trump by 37 points, and ID-2 voted for him by 24 points. So even as ID-2 seems likelier to take on more of the Boise area to balance out the population of the two districts, it should still be a Safe Republican seat. Trump won Idaho overall by 31 points, his fifth-best state (neighboring Wyoming was his best).

Idaho is the nation’s second-fastest-growing state, and it’s not out of the realm of possibility that it could add a third seat in the 2030 reapportionment. Randy Stapilus, a former Idaho newspaper reporter, speculated in a May column about what a three-district Idaho map might look like. One possibility would be to combine Ada with neighboring Canyon County, both fast-growing counties that together could have roughly the proper population size if the state had three districts. But Trump would have carried that hypothetical district by 13 points, which is a good illustration of the GOP strength in Idaho even in its most populated area.

ILLINOIS

Number of seats: 17 (-1 from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 12-6 D

Current party breakdown: 13-5 D

Most overpopulated district: IL-7 (Downtown/West Side Chicago)

Most underpopulated district: IL-17 (Northwest Illinois)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Democrats

With a 13-5 edge in the Illinois U.S. House delegation already, Democrats are not going to be able to squeeze a ton more out of the Land of Lincoln. But they should be able to do better than they are doing now and, just as importantly, they should be able to better protect some of the competitive districts they already hold.

As they draw the maps in Illinois, Democrats will be building off their gerrymander from a decade ago — one that worked out great for them in the long run of the decade, though not really as intended.

Republicans won 11 of Illinois’s 19 House seats in 2010, but Democratic control of the state legislature paired with then-Gov. Pat Quinn’s (D) narrow victory allowed Democrats to draw the state’s map. They designed a map that they hoped would elect 13 Democrats and five Republicans. Democrats came up one seat short in 2012, as now-Rep. Rodney Davis (R, IL-13) narrowly held a central Illinois seat that covers the state capital, Springfield, as well as Champaign-Urbana, home of the flagship University of Illinois campus. Davis was pushed hard again in 2018, but he remains in office. Republicans struck back in 2014, winning the affluent and highly educated northern Chicago suburban district IL-10 as well as the ancestrally Democratic but Republican-trending IL-12 in southwest Illinois. Democrats won IL-10 back in 2016, and now-Reps. Sean Casten (D, IL-6) and Lauren Underwood (D, IL-14) flipped two of the five seats “reserved” for Republicans at the start of the decade by the Democratic gerrymander. Democrats held all 13 of their seats in 2020, although Underwood only won by a little over a point. Meanwhile, Rep. Cheri Bustos (D, IL-17) won her gerrymandered district consistently throughout the decade, but she only won by four points last year in the Obama-to-Trump district. She is retiring, complicating Democratic efforts to hold her seat.

Illinois, one of the few states that actually lost population from 2010-2020, is once again losing a House seat. Two-thirds of Illinois’s population lives in either Chicago’s Cook County or one of its five surrounding “collar counties” (DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry, and Will). Democrats hold all 13 districts that cover these six counties with the exception of Rep. Adam Kinzinger’s (R) IL-16, which takes in a bit of the Chicago collar. Meanwhile, Republicans hold four of the five outstate districts, with IL-17 as the only exception.

So Democrats have several obvious goals in gerrymandering:

— Make sure that the eliminated district is one of the five current Republican seats.

— Protect Underwood in her exurban Chicago seat and, less pressingly, Casten, without endangering any of the other Democratic Chicagoland seats.

— Reconfigure the downstate districts to go after Davis in IL-13. This likely will be done in part by removing East St. Louis, a Democratic downstate bastion, from IL-12 and putting it in IL-13. This was once a Democratic vote center in IL-12, which Democrats held at the start of the decade, but now that Rep. Mike Bost (R, IL-12) has grabbed a strong hold on the district, there’s no sense, from a Democratic perspective, of “wasting” those Democratic votes in his district.

— Keep IL-17 blue.

Accomplishing all of these goals would result in a 14-3 Democratic map, an improvement on the current 13-5 advantage. Twitter mapmaker @UMichVoter showed how this could be done recently: IL-13 becomes a Biden +12 district by extending down to East St. Louis and continuing in a thin strip that takes in Springfield and Champaign. Chicagoland is reconfigured in such a way to put Underwood in a double-digit Biden seat, and IL-17 is changed into a Biden +9 seat. Democrats would be favored in those kinds of seats, although they could lose them under the right circumstances. Assuming the map worked as Democrats would want, they would confine Republicans to just three districts and quite possibly push out Kinzinger, a Trump critic who likely would have a hard time in a primary. Another Twitter mapmaker, Ryan Brune, suggests a more modest, 13-4 Democratic gerrymander.

The bottom line in Illinois is that Democrats are likely to come out of the state with at least a slightly bigger edge in the state than they hold now — indeed, they almost certainly have to if they are to retain the House, given their redistricting problems elsewhere.

One side note: Illinois Republicans may have been hoping to use the state courts to combat Democratic gerrymandering much as Democrats have used Democratic state courts in states such as North Carolina and Pennsylvania to combat Republican gerrymandering in those states. And they appeared to have an opening: One of the Democratic justices lost a retention election last November, setting up an open-seat election in 2022. The court is 4-3 Democratic, so winning that seat without any other changes would flip the court to Republicans. In response, Democrats re-drew the judicial districts, ostensibly to update the maps to better account for current population — they had been last drawn in 1964, although judicial districts are not subjected to the same equal population requirements as legislative districts — but also to improve their chances of maintaining control of the court.

INDIANA

Number of seats: 9 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 7-2 R

Current party breakdown: 7-2 R

Most overpopulated district: IN-5 (Northern Indianapolis suburbs/exurbs)

Most underpopulated district: IN-8 (Southwest Indiana)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

Despite being for decades the most clearly Republican state among the seven discussed here, Indiana once had a reputation for competitive House races. Democrats overcame a Republican gerrymander in the 1980s and ended up holding eight of the state’s 10 seats by the end of that decade. More recently, in the 2000s, Indiana featured perhaps the decade’s most intense congressional rivalry, as Mike Sodrel (R) and Baron Hill (D) battled for four straight elections over southern Indiana’s 9th District: the incumbent Hill fought off Sodrel in 2002 but then lost to him in 2004. Hill came back and beat Sodrel in 2006 and then beat him again in 2008.

But in 2010, Hill lost to Todd Young (R), who is now in the U.S. Senate. And Indiana’s famously competitive House elections became much less so. Part of that was because of Republican-controlled redistricting, but also because of political trends in the state, as traditional Democratic strength withered outside of the Indianapolis metro area. In 2012, Democrats only narrowly lost northern Indiana’s IN-2, which Joe Donnelly (D) left behind to successfully run for Senate after Republicans redrew the district, but Rep. Jackie Walorski (R, IN-2) has easily held the district since. Democrats also competed for IN-5, a highly-educated suburban/exurban district that runs north of Indianapolis, in 2020, but now-Rep. Victoria Spartz (R) held it in an open-seat race. That about sums up all of the major House-level competition in Indiana over the past decade, where Republicans have won a 7-2 edge in each election.

In redistricting, Republicans have a liability to address, and an opportunity to consider.

The liability is the aforementioned IN-5, where Mitt Romney’s 17-point edge in 2012 contracted to just a two-point margin for Donald Trump last year. Shoring up the fast-growing district likely will be a priority.

The opportunity is in northwest Indiana, where Democratic performance has softened in IN-1, held by first-term Rep. Frank Mrvan (D). Obama’s 2012 margin of 24 points fell to just nine for Biden in 2020. If Republicans got aggressive, they could try to slice up the district, although they may also just keep it intact with the hope that trends in the Gary/Hammond-based Chicago-area district continue to push it toward Republicans over the course of the decade — given its heavily blue collar character, this is a real possibility. So even without aggressive redistricting, Republicans could win an 8-1 edge in the state sometime this decade, although they have to be careful to stay ahead of Democratic trends in Greater Indianapolis.

IOWA

Number of seats: 4 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-2 split

Current party breakdown: 3-1 R

Most overpopulated district: IA-3 (Des Moines, Southwest Iowa)

Most underpopulated district: IA-4 (Northwest Iowa)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Split

Iowa typically has one of the cleanest redistricting processes in the country. The state’s nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency drafts the maps, and the state legislature can either accept them as drawn or ask for a second draft. The legislature then decides on the second draft from the LSA, which it can accept or reject but not modify. Only if the legislature rejects a third draft can legislators modify the maps themselves.

This process has been in place since the 1980 census, but Republicans control state government and hypothetically could gerrymander — there is a strong norm in Iowa toward nonpartisan redistricting, but norms are not legally binding. The LSA should have the first map drafts in place by Sept. 16, which means the state appears as though it will miss a state constitutional deadline for finalizing the maps. However, there are indications that the Iowa Supreme Court, which is tasked with drawing the maps if the state misses the deadline, will allow the usual process to unfold. Iowa law also requires the state’s maps to be compact, to the extent possible, and the state preserves whole counties in congressional redistricting (Iowa, along with West Virginia, is the only state with more than one House district that does not have any split counties among its districts).

The current map has featured consistent competition. Three of the state’s four districts (IA-1, IA-2, and IA-3) changed hands at least once last decade, and even the fourth, IA-4, which is markedly more Republican than the others, has been competitive, thanks in part to the weakness of controversial former Rep. Steve King (R), who lost a primary in 2020. Democrats won three of the four districts in 2018. Republicans won two back last year, boosted by another strong performance by Donald Trump in Iowa. One of those two victories was by just six votes in IA-2.

Trump carried IA-4 by 27 points, but the other three districts are marginal: Trump’s margins in IA-1 and 2 were 3.5 and 4 points, respectively, and only a couple tenths of a percentage point in IA-3, held by Rep. Cindy Axne (D), the lone Democrat in the state’s congressional delegation.

IA-3 is the only one of the state’s four congressional districts that is overpopulated (by roughly 60,000 people). The most underpopulated district is IA-4, which covers the northwestern part of the state and is the state’s most Republican district. It needs to add about 30,000 people, and the two eastern districts, IA-1 and IA-2, each need to add roughly 17,000 and 12,000 people, respectively. Des Moines (Polk County) and its most populous surrounding county, Dallas (a growing, Republican-but-Democratic-trending part of the Des Moines area), form the core of IA-3. They have, combined, close to 600,000 residents, about three-quarters of the roughly 800,000 needed for one of the four Iowa congressional districts.

So one possible outcome is that IA-3 sheds some of its sparsely-populated and Republican rural counties. It would still be a swing district, but it wouldn’t take much to turn it into a Biden-won seat. Democrats probably would be happy if two neighboring eastern Iowa Democratic counties, Linn (Cedar Rapids) and Johnson (Iowa City/University of Iowa), were united in the same district (they are currently split between IA-1 and IA-2). Republicans, meanwhile, should reasonably believe they would have a good chance of a 4-0 delegation, at least in 2022, if the maps don’t change all that much. IA-4 is solid with new incumbent Rep. Randy Feenstra replacing the outrageously offensive King, first-term Reps. Ashley Hinson (R, IA-1) and Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R, IA-2) have a decent chance to hold Trump-won seats in a midterm environment with a Democrat in the White House (although Hinson has drawn a credible challenger), and IA-3 should be among the most vulnerable Democratic districts next year absent a significant assist from redistricting.

If Republicans end up drawing the maps, they could try to improve their chances of winning a 4-0 edge or, if they wanted to be conservative, could try to lock in a durable 3-1 delegation by creating something of a Democratic vote sink, perhaps connecting Des Moines to Iowa City while strengthening the new Republican incumbents in the eastern districts.

KANSAS

Number of seats: 4 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 4-0 R

Current party breakdown: 3-1 R

Most overpopulated district: KS-3 (Kansas City suburbs)

Most underpopulated district: KS-1 (Rural west)

Who controls redistricting? Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

When it comes to congressional redistricting, Kansas may be to Republicans what New Mexico is to Democrats. In these small states, the party that controls redistricting may go after the delegation’s lone minority party member — but doing so can be risky, and an aggressive plan may have some cumbersome logistical hurdles.

During the first decade of the 2000s, Democrats held KS-3, in the Kansas City suburbs, with veteran Blue Dog Dennis Moore (D, KS-3) and, for a term, rented the adjacent KS-2. In 2006, Rep. Jim Ryun (R, KS-2) seemed blindsided by the anti-Republican tenor of the cycle, as Democrat Nancy Boyda beat him 51%-47% to represent a seat that contained wide swaths of eastern Kansas. The next cycle, Republicans made the race a priority; in a reversal of 2006, state Treasurer Lynn Jenkins ran against Boyda and won 51%-46% — this was one of House Republicans’ few pickups in an otherwise grim cycle. Republicans have held KS-2 since then, and in 2010, as Moore retired, his KS-3 fell into Republican hands.

Though some conservative Republicans pushed for an aggressive map, they ran into resistance from some in their own party, as well as Democrats — over the last decade, warring between moderates and conservatives has defined Kansas Republican politics. When the situation ended up in the courts, a map that avoided large-scale changes was enacted (though they redrew KS-3, which favored Barack Obama 51%-48% in 2008, into a seat that gave John McCain a slight edge).

While the ultimate map was tamer than what some conservative partisans had pushed for, during the first three cycles of the decade, it still worked out fine for Republicans. Between 2012, 2014, and 2016, all GOP congressional nominees won by double-digits each cycle. In fact, some of the most-watched congressional races in Kansas were internecine. In 2014, Rep. Mike Pompeo (R, KS-4) easily beat back a primary challenge from his predecessor, Todd Tiahrt. Then, in 2016, and with help from the Farm Bureau, first-time candidate Roger Marshall primaried then-Rep. Tim Huelskamp (R, KS-1), a Tea Party bomb thrower who was an irritant to GOP leadership. (Marshall just won election to the Senate last year.)

After the 2016 election, Pompeo was tapped to serve in the Trump Administration. In a nationally watched April 2017 special election, then-state Treasurer Ron Estes held Pompeo’s Wichita-area seat by only a 52%-46% margin — that result was down markedly from the 27-point spread Trump posted in the district, and, with the midterms on the horizon, was seen as a harbinger of Democratic enthusiasm.

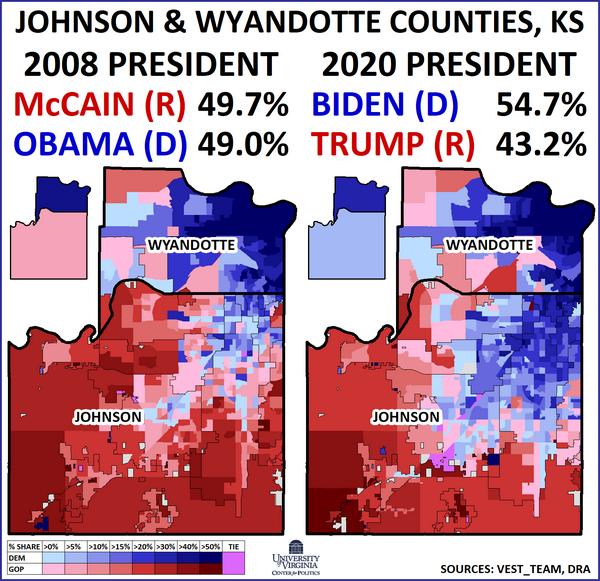

Ironically, Estes ended up being fine in the 2018 regular election, but Democratic gains materialized elsewhere in the state. As the suburbs soured on Trump, Democrats regained KS-3: Democrat Sharice Davids ousted then-Rep. Kevin Yoder (R, KS-3) by nearly 10 points. Democrats also only narrowly missed out on KS-2 — though the district contains the blue cities of Lawrence and Topeka, it has about two-dozen counties that are considerably redder. In 2020, no seats changed hands.

On paper, Republicans hold veto-proof majorities in the state legislature, and some of their members have entertained the idea of a 4-0 GOP map. Democrats have some leverage, though. Some Republicans may balk at a map that is too aggressive — in other words, a replay of last decade may be in the cards. There could be enough GOP defections to defeat a plan targeting Davids, or to sustain Gov. Laura Kelly’s (D-KS) veto of such a plan. Moreover, five of the seven justices on the state Supreme Court were appointed by Democratic governors, so Republicans may not find a sympathetic audience if their plans end up in court.