KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— If no candidate receives a majority of Electoral College votes, the U.S. House of Representatives elected in the 2024 election would decide the presidency.

— Republicans are very likely to continue to control enough House delegations to select the GOP nominee as the winner, meaning that 269 is effectively the winning Electoral College number for Republicans, while it’s 270 for Democrats.

— Republicans currently control 26 of the 50 House delegations, the bare majority to win in the House if the Electoral College does not produce a majority winner.

Breaking an Electoral College tie

Next year, 2024, coincides with a pair of bicentennial anniversaries in American presidential election history.

The presidential election of 1824 was the first one in which there is a tabulation of the actual popular vote for president, albeit not from every state. A majority of states in the Union at the time had adopted a popular vote for presidential electors; previously, presidential electors had generally been chosen by state legislatures. Thus, one can describe 2024 as representing the 200th anniversary of a popular vote for president, even if the totals represented only 18 of the 24 states voting at the time. (This history is from What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 by Daniel Walker Howe).

The 4-way presidential race failed to produce a majority winner in the Electoral College: Andrew Jackson finished first, with 41% of the popular vote and 38% of the electoral votes, short of the majority required for election. The election went to the House of Representatives, which brings us to the second bicentennial anniversary in 2024: 1824 was the most recent election in which the House decided the presidential winner. The 12th Amendment stipulates that in the event no one wins a majority of the Electoral College votes, the House chooses among the top 3 finishers in the Electoral College, with each state’s delegation getting a single vote. The House ended up backing the second-place finisher, John Quincy Adams. Jackson would get his revenge in a landslide victory 4 years later.

The dueling anniversaries illustrate the conflicting realities at the heart of the American presidential election system. On one hand, the 1824 election represents an important step in the evolution of the mass electorate’s role in presidential elections, with the franchise slowly being expanded to women, Black Americans, 18-20 year olds, and others over the course of the past 2 centuries. The expansion of the franchise has at its heart a very basic assumption — the voters should pick the president.

On the other hand, the dusty, old system used in 1824 to resolve an inconclusive election endures, lying in wait to befuddle most Americans (and enrage many of them) if it is ever needed. It is reminiscent of the Electoral College itself — an ancient foundation upon which we have constructed our modern representative democracy. Like the Electoral College, the House tiebreaking procedure was created at a time before rank-and-file voters were truly involved in selecting the president. So if the people (the voters) don’t produce a clear verdict, they effectively forfeit the choice to an elected representative body, albeit divided in such a way (into 50 state-level subgroups) that might not make it representative of the full membership of the whole House. This is not neatly compatible with majoritarian ideals — but, then again, neither is the Electoral College or the U.S. Senate. Would we design a system like this today? The answer is obvious, but it also just doesn’t matter in the context of the upcoming election, as the system is not going to change. So we need to understand it in order to be ready for all possible outcomes.

The House tiebreaking procedure — unlike the Electoral College, which is endlessly debated and analyzed — is not a prominent feature of election analysis and commentary, probably because it has never been used in anyone’s lifetime and because the odds of it being used are so low. But as we showed in yesterday’s Crystal Ball, a tie came close to happening in 2020, and there are plausible scenarios under which it could happen in 2024.

If there is a tie, Republicans continue to have an advantage in the House tiebreaking procedure, and they are very likely to retain it following the 2024 election, regardless of which party wins the overall House majority.

That’s because in the House tiebreaking vote, each of the 50 states gets a single vote, and a majority of the votes (26) are required to select a president. Presumably, members of the party that hold a majority of seats in a given delegation would cast their vote for their party’s presidential candidate. Evenly-divided states might end up unable to cast a vote. The new House — meaning the one elected in 2024, not the current one — would break the tie. The Senate, meanwhile, would select the vice president. That is a more straightforward process, as each of the 100 senators gets a single vote.

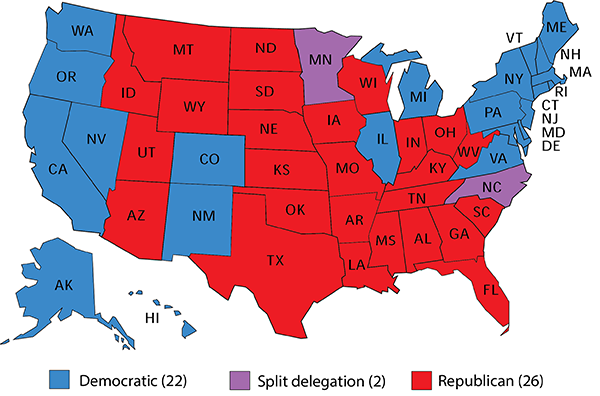

Map 1 shows the control of the individual House delegations by party.

Map 1: Current control of U.S. House delegations

Republicans currently control 26 of the 50 House delegations, the bare minimum needed to elect the president in a House vote. Democrats control 22, and a pair of states — Minnesota and North Carolina — are split. This is almost the exact same division as there was the last time we wrote about this, in advance of the 2020 election, when Republicans held a 26-23-1 advantage (a handful of states have changed hands either way since then). Back when we last looked, in September 2020, Democrats held a 232-198 advantage in the House, with 4 vacancies at that time and with now-former Rep. Justin Amash of Michigan serving as an independent after leaving the GOP. Now, Republicans will have a 222-213 majority once Rep.-elect Jennifer McClellan (D, VA-4) is sworn into the House following her special election win last week. Democrats held the majority back in 2020, but now Republicans do.

We recently released our initial House ratings for 2024. Those ratings help inform our state-by-state assessments of the delegations. Let’s start with the delegations we consider to be effectively Safe Republican, then those that are Safe Democratic, and finally those where there is at least a little bit of a question about which side will control the delegation following next year’s elections.

First of all, 22 states have House delegations we consider Safe Republican in 2024: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Meanwhile, Democrats have just 13 Safe delegations of their own: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

That leaves 15 states where there is at least some question about which party will control the delegation following 2024. We’ll go through them in alphabetical order:

Alaska: Rep. Mary Peltola (D, AK-AL) is the single member of this House delegation. In addition to facing what will likely be a competitive reelection challenge, Peltola also would face pressure to cast her vote for the presidential winner in her state, assuredly a Republican in a situation where a tie is possible (we could imagine a Democrat carrying Alaska for president, but only as part of a national landslide). Leans Democratic

Arizona: Republicans flipped this delegation from 5-4 Democratic to 6-3 Republican last year. However, 2 of the GOP seats are very marginal, so Democrats could win the delegation back as soon as next year. Leans Republican

Colorado: Democrats have a 5-3 edge, but Rep. Yadira Caraveo (D, CO-8) only very narrowly won a new swing seat, and Rep. Lauren Boebert (R, CO-3) also came very close to losing a Republican-leaning seat. If things broke right for Republicans, they could get to a 4-4 tie. Leans Democratic

Iowa: Republicans have a 4-0 edge, which they completed last year with Rep. Zach Nunn’s (R, IA-3) very close win over former Rep. Cindy Axne (D) in the marginal Des Moines-based IA-3. Democrats would have to win that seat back and flip 1 of 2 competitive but Republican-leaning eastern districts to get to a tie (we rate both seats Likely Republican). Iowa may not be quite Safe Republican, but it is close. Likely Republican

Maine: Republicans could forge a tie here if they knocked off Rep. Jared Golden (D, ME-2), who holds a Trump-won seat. Leans Democratic

Michigan: Democrats hold a narrow 7-6 statewide lead, but they are defending the open MI-7, which was very narrowly decided for president in 2024. Reps. Dan Kildee (D, MI-8) and John James (R, MI-10) also hold marginal districts. Toss-up

Minnesota: The delegation is split 4-4, and the only truly competitive seat is held by Rep. Angie Craig (D, MN-2), but it is Biden +7 and Craig won a solid, 5-point victory last year. Leans Split

Montana: Republicans should hold on to their 2-0 edge here, but the seat held by Rep. Ryan Zinke (R, MT-1) is somewhat competitive (Trump +7) and Zinke won by just 3 points last year in an open-seat race. He may or may not run for Senate. Leans Republican

Nevada: The Democrats’ gerrymander helped preserve the party’s 3-1 edge here, and they remain favored in all 3 seats to start this cycle. Likely Democratic

New Hampshire: Republicans hypothetically could compete for either of the state’s seats, but both are a bit bluer than the nation as a whole. Likely Democratic

North Carolina: The state is split 7-7 right now, but it appears to be only a matter of time before Republicans redraw the map, which was imposed last cycle by a Democratic-majority state Supreme Court that has now flipped to Republican control. Assuming the Republicans end up being able to gerrymander North Carolina, they should easily win a majority of the state’s seats next year. Likely Republican

Oregon: Democrats have a 4-2 statewide edge, and the most competitive district is OR-5, which Rep. Lori Chavez-DeRemer (R) flipped last year. Likely Democratic

Pennsylvania: Democrats hold a slim 9-8 edge here, but Reps. Matt Cartwright (D, PA-8) and Susan Wild (D, PA-7) are defending Toss-up seats. Toss-up

Virginia: Rep. Jen Kiggans (R, VA-2) flipped the state’s most marginal district to cut the Democratic edge to 6-5, but Republicans will have to unseat Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D, VA-7) in a Biden +7 district to flip the delegation. Likely Democratic

Wisconsin: Republicans hold what on the current map is a fairly solid 6-2 statewide lead after flipping WI-3 last cycle, but if a Democratic-aligned justice wins next month’s state Supreme Court election, Democratic-aligned justices will control the court 4-3. That could open the door to litigation that would force a new congressional district map, perhaps splitting the Milwaukee and Madison areas and getting the delegation to 4-4. There are a lot of what ifs here, but the situation merits watching. Likely Republican, for now

So Republicans start with 22 Safe delegations. Iowa and North Carolina are likely to be delegations 23 and 24, and we favor Republicans to hold the majorities in Arizona and Montana. That’s 26 right there, and it doesn’t even include Wisconsin because of the redistricting situation. It also wouldn’t take much for Republicans to flip the Toss-ups, Michigan and Pennsylvania, particularly in a world where an Electoral College split is happening, which would suggest a close and competitive presidential election.

Meanwhile, it’s exceedingly difficult to imagine Democrats getting to a bare majority themselves, 26, in the midst of an otherwise competitive national election. There are circumstances where they could deny Republicans a majority by winning or forcing ties in almost all of the competitive states noted above.

How a deadlocked House would resolve a presidential election if neither side had a majority of delegations is anyone’s guess. Perhaps it wouldn’t. It is also unclear how a majority party that nonetheless did not control a majority of delegations would act from a procedural standpoint. If the Senate could produce a vice president (that chamber is 51-49 Democratic but is very gettable for Republicans next year), that vice president would serve as president if the House does not produce a president.

The bottom line here is that Republicans appear likely to maintain control over the presidential tiebreaking process in the House, meaning that their Electoral College magic number is effectively 269, not 270.

P.S. What if a third party candidate gets votes?

One other alternative that could throw the election to the House is a scenario in which a third candidate wins enough electoral votes to prevent either of the major party nominees from getting to 270. This would make the situation more comparable to 1824, when there were multiple, credible candidates who got electoral votes, making it difficult for anyone to get a majority.

While there have been protest votes cast by faithless electors in some instances over the past few decades, the last time a third party candidate actually won electoral votes in his own right was George Wallace, the Dixiecrat segregationist who way back in 1968 carried 5 Southern states and 46 electoral votes. Richard Nixon still won the Electoral College, but enough states were close that had things gone a little differently, the election could have gone to the House (which Wallace wanted as a way to dictate terms to the eventual winning candidate). That led to a serious effort to amend the Constitution to eliminate the Electoral College. President Nixon supported a constitutional amendment that easily passed the House, but it died in the Senate (Washington Post history blogger Gillian Brockell wrote about this after the 2020 election).

What third party candidate could win electoral votes in 2024? While the likeliest answer is that no one will, Donald Trump is the most plausible candidate. Republicans have long feared Trump running as a third party candidate, and he could potentially do so if he loses the 2024 Republican nomination (we’ll believe it when we see it, but one cannot rule anything out with Trump). A recent poll by Republican pollster Whit Ayres for the Bulwark found that 28% of Republican primary voters would back Trump in a general election even if he ran as an independent — a group the publication’s Sarah Longwell called the “Always Trumpers.” Again, this is all hypothetical, but if Trump ran as a non-major party candidate, got on ballots, and actually attracted and maintained this kind of support, he could potentially win some states — West Virginia, where he turned in a blockbuster performance for a GOP presidential nominee, comes to mind.

In all likelihood, this kind of GOP split — where Trump was strong enough to be winning states despite not being the GOP nominee — would swing the election to the Democratic nominee as opposed to forcing the election to the House (it could be a version of the 1912 election, when a GOP split allowed Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency). Although if this 3-way 2024 election did go to the House, imagine the political theater of House Republicans having to choose between their party’s nominee and Trump.

OK, we’ll admit, our imagination might be getting a bit out of hand here. Meanwhile, we very much hope that the 200-year streak of the House not having to pick a presidential winner goes on for many years longer. Because if that streak stops, Americans are going to be reminded just how arcane our nation’s electoral rules can be.