|

Dear Readers: Join us tomorrow at 2 p.m. for our Sabato’s Crystal Ball: America Votes webinar. In addition to breaking down the election with just days to go, we’ll be joined by members of the Decision Desk HQ team, which will be independently reporting results Tuesday night. They’ll give us some tips about what to watch for on Election Night — and beyond. We are releasing this week’s episode a little differently as a way to address some persistent audio issues from previous episodes. Instead of livestreaming the webinar, we will be posting it directly to our YouTube channel at 2 p.m. eastern on Thursday. Just visit our YouTube channel, UVACFP, at 2 p.m. (or whenever you want), and look for Episode 11 of the Sabato’s Crystal Ball: America Votes webinar. The direct link will also be available on the Center for Politics’ Twitter account (@center4politics) at around 2 p.m. Thursday. The Center for Politics is also hosting New Zealand’s ambassador to the United States, Rosemary Banks, at a virtual public event today at 4 p.m. Banks will speak about the relationship between New Zealand and the United States, the country’s successful response to COVID-19, and other topics. Those who would like to attend may register via this link. Today, we continue with our States of Play series. Associate Editor J. Miles Coleman and former Crystal Ball intern Tommy Dannenfelser look at the changing politics of the Center for Politics’ home state, Virginia. This is our seventh installment of our detailed look at the key states of the Electoral College; previous editions featured Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Ohio and Florida. We’re also happy to welcome Lakshya Jain as a guest writer — he’ll explore the concept of electoral “elasticity” and apply it to several swing states. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Though it was considered a key swing state in the Obama era, Virginia is now a solidly blue state that has seen little attention from either presidential campaign.

— In a sign of the times, after 2019, Democrats now hold almost every significant office and both state legislative chambers in the Old Dominion.

— In 2016, Virginia saw some ticket-splitting at the federal level, but 2020 may be a more straight-party year.

Virginia’s shift blue

The Commonwealth of Virginia, or the Old Dominion as it is sometimes referred to, is known by many political observers for its conservative political history — from its time as the capital of the Confederacy to its decades-long control by the segregationist Byrd machine. Yet there has been a noticeable shift in Virginia’s political dynamic in recent years. Most of the swing states that could decide this year’s election — such as Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Florida — have been considered “purple” states since the hotly-contested Bush/Gore 2000 election. But over those 20 years, Virginia has gone from comfortably GOP to a state that few doubt that Joe Biden will carry in a couple of weeks — and perhaps by double-digits, as much polling suggests.

Aside from its red presidential voting patterns, at the dawn of the 21st century Virginia Republicans had reason to feel optimistic about their future prospects. In the 1997 elections, an ascendant GOP won all three state elected offices: governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general. This marked the first time since Reconstruction that the party of Lincoln would hold all three of the state’s top jobs. In the 2000 election, Republicans built on this success, as then-former Gov. George Allen (R) ousted Sen. Chuck Robb (D). Like Allen, Robb was a former governor — he served from 1982 to 1986, and then when a Senate seat opened up in 1988, he waltzed into it with 71% of the vote, carrying every locality.

In surveying Virginia’s current political situation, one finds a Republican Party that’s struggling for relevance: the GOP has not won a statewide contest since 2009. Democrats have held both its U.S. Senate seats for over a decade, and after 2018, they claim seven of its 11 congressional districts. Its three statewide offices have been in Democratic hands since 2014, and in something of a natural manifestation of larger trends, both chambers of the legislature flipped blue in 2019.

Moving back to the national picture, the Commonwealth was one of about a dozen states where Hillary Clinton’s 2016 margin, 5.3%, represented an improvement from Barack Obama’s in 2012, 3.9% — though Clinton may have received something of a local boost from her running mate, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA), a known commodity in state politics. While Virginia won’t be especially pivotal in the Electoral College, it may be worth a look at some of the factors, and history, that precipitated the state’s political sea change.

From red to blue… very quickly

To examine Virginia’s political transition, it is important to look back at Virginia’s past. The Commonwealth was essentially a one-party state from the post-Reconstruction era to 1969, when the state elected its first modern Republican governor, Linwood Holton. Prior to then, conservative Democrats dominated the state’s politics.

From a regional perspective, Virginia has stood out among Southern states. Franklin Roosevelt, in 1944, was the last Democratic presidential nominee to carry all 11 states of the Old Confederacy. Since then, Jimmy Carter, in the 1976 election, has come the closest to replicating that. Against Republican Gerald Ford, Carter swept 10 of those 11 states — only missing out on Virginia. At this time in the Commonwealth’s history, Northern Virginia was seeing a burgeoning population, and this suburban region was voting Republican in the interest of fiscal issues. Chesterfield and Henrico counties, two suburban counties on either side of Richmond, also contributed to the Republican vote — they’d often back GOP candidates with about 60% of the vote. A curious point is that looking forward to 2016, the political maps of the 1976 and 2016 elections tell the same tale: Virginia stood out as the only contrarian state in the Old Confederacy.

Virginia would go on to usher in its liberal era decisively in the period from 2000 to the present day. The Commonwealth would vote for Republican George W. Bush by 8 points in 2000, but this Republican tilt would steadily erode. In 2001, the following year, Democrat Mark Warner would win the governorship in part by swaying voters from the Commonwealth’s southwest, counties that would vote solidly Republican by 2016. Warner boasted approval ratings as high as 80% during his term as governor. Virginia’s constitution limits its governors to a single consecutive term, and when he left office, voters would promote his lieutenant governor, fellow Democrat Tim Kaine.

Before his time as a statewide official, Kaine was mayor of Richmond. He was particularly influential in Virginia’s leftward shift — he essentially drew the current Virginia electoral map in his 2005 gubernatorial win. Kaine won 52%-46% that year, a shade better than Warner’s 52%-47% four years earlier, but lost ground in most rural localities, particularly the southwest. Most of Kaine’s gains over Warner came in what the Crystal Ball and others have dubbed the “Urban Crescent.” The crescent begins in Northern Virginia, where some localities — such as Loudoun County — are still seeing considerable growth, then follows Interstate 95 down to metro Richmond, and concludes in the Hampton Roads area, where the largest locality is the swingy Virginia Beach. The Urban Crescent is a fixture of Virginia politics, reappearing consistently in maps of modern Virginia elections.

In the anti-Bush 2006 midterms, Democrats narrowly ousted Sen. George Allen (R) — whose electoral status in the Commonwealth once seemed unassailable — with first-time candidate Jim Webb, who had some bipartisan credentials from his time serving in the Reagan administration. Though many observers attributed Allen’s loss to a gaffe he made during the campaign, Webb’s winning coalition looked a lot like Kaine’s the year earlier, a sign that recent shifts were solidifying.

Virginia’s dynamic transition to the Democratic column continued into the 2008 presidential election. Early in the cycle, Barack Obama’s campaign identified it as a Bush state that could potentially vote blue. After several stops there, and an aggressive voter registration operation, Obama defeated McCain in the Old Dominion by a sizeable 6.3 points — it tracked closely with his 53%-46% popular vote margin. This was a monumental year for Democrats in Virginia, as no Democratic nominee had carried it since Lyndon Johnson in 1964. In 2012, Virginia was seen as a truly purple state, and both sides made serious plays for its 13 electoral votes — in terms of presidential campaign appearances, it was the third most-visited state that cycle. In the end, it was a perfect bellwether for the national mood: it went 51%-47% for Obama, elected a Democrat to the Senate (the mavericky Webb retired after a single term, and was replaced by Kaine, who Obama helped recruit), and sent a majority-Republican delegation to the House. It was one of just four states where the result was within five percentage points, along with Florida, North Carolina, and Ohio.

In 2016, Virginia voted about three percentage points left of the national popular vote, which was an indication that it was starting to drift off the presidential playing board. Hillary Clinton cratered in the rural areas — in the Appalachian southwest, Trump cleared 80% of the vote in some localities — but her gains in the Urban Crescent delivered the state. Trump’s “drain the swamp” rhetoric was a non-starter to the many federal government employees that reside in Northern Virginia’s suburbs. Loudoun County, which is situated about 30 miles west of Washington D.C., has seen explosive population growth over the last decades. George W. Bush carried it twice, by double-digits, and it was a decent national bellwether in the Obama years. But it zoomed left for 2016, giving Clinton a 55%-38% vote — though Trump’s drop in some of the state’s other suburbs was less severe, his weak standing in the state’s metro areas makes Virginia tough lift for him.

Given the steady Democratic trend in the Old Dominion, what can we expect from the upcoming presidential election? Polling has been scarce — naturally, as Virginia has exited the “swing state” category, fewer national observers, and pollsters, have taken interest in it — but most of it shows Biden up double digits, and the Crystal Ball currently rates the state as Likely Democratic. So after just two presidential cycles, 2008 and 2012, as a purple state, Virginia is now fairly blue.

Warner, Kaine illustrate electoral shifts

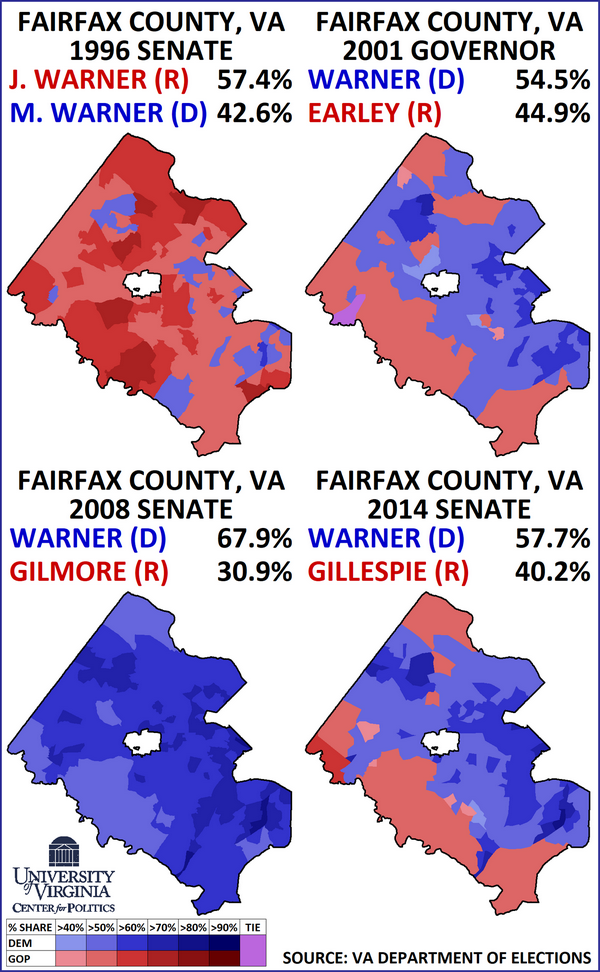

Aside from its presidential contest this year, Mark Warner, now in his second term in the U.S. Senate, will be running for a third term. In many ways Warner, who was first a statewide candidate in 1996, tracks well with many of the coalition shifts the state has seen since then. In Fairfax County — bumping up against Washington, D.C., this is Virginia’s most populous county, casting nearly 15% of the statewide vote in the 2016 election — Warner’s results have ranged from heavy losses to landslide wins (Map 1).

Map 1: Mark Warner’s elections in Fairfax County

In Warner’s first attempt at state office, he challenged Republican John Warner — the two were not related — in 1996. By today’s standards, that 1996 election seems outright bizarre. Mark Warner aggressively courted rural voters in the southern part of the state, while John Warner, who was known for his moderate brand of Republicanism (in 2016, he went on to endorse Clinton), played well with suburbanites at the time. The Republican Warner’s position on the Senate Armed Services Committee also likely helped in Fairfax County, which houses some intelligence agencies and military installments. John Warner won that race by 5% overall, and claimed a 15% margin in Fairfax, running well ahead of his party’s presidential nominee, Bob Dole, there.

In 2001, Mark Warner rebounded to win the gubernatorial race. In something of a flip from 1996, he won overall by 5%, but carried Fairfax County by a solid, though perhaps not overwhelming 55%-45%. After his tenure as governor concluded, in 2006, he was often mentioned as a potential presidential contender for 2008. But when his old opponent, John Warner, retired that year, he ran for the Senate seat again. Though Warner faced another former governor in the general election, Republican Jim Gilmore, he was an overwhelmingly popular figure in the state — with a favorable national environment, he was an especially strong candidate. Warner won his Senate seat 65%-34% that year, and did a few points better in Fairfax County.

In 2014, Warner was up for reelection, and one of the biggest surprises of the night was his margin. Though Warner was favored for much of the campaign, former Republican National Committee chairman Ed Gillespie held him to just a 49%-48% advantage. But by 2014, Fairfax had become a solidly Democratic county, supporting Warner by nearly 18 percentage points — in fact, as returns came in that night, Gillespie had the lead until Fairfax started reporting.

Even with limited polling of the Senate race, Warner is a big favorite in November. That said, Warner has drawn a credible opponent in Army veteran Daniel Gade (R), who lost a leg in Iraq in 2005. Gade is a stronger candidate than Corey Stewart (R), the ideologue who Kaine easily defeated in 2018, and Gade also outraised Warner in 2020’s third quarter, although Warner has an overall spending advantage and a big warchest. More importantly in terms of the statewide result, Gade doesn’t have the type of red environment that Gillespie did in 2014 — with presidential turnout, Warner and Biden may achieve similar statewide margins (polling has generally shown the two running fairly close to each other, although a Washington Post-Schar School poll conducted in mid-October showed Biden leading by 11 and Warner leading by 18).

In 2016, there was considerable ticket splitting in Virginia, and much of it was to the benefit of Republicans. In Northern Virginia’s 10th District, voters favored Clinton 52%-42%, but reelected then-Rep. Barbara Comstock (R, VA-10) by 6% — Comstock drew significant crossover in parts of Fairfax County. Down in the Virginia Beach area, the swingy 2nd District narrowly favored Trump, but in the congressional race, then-state Rep. Scott Taylor won it by 23% for the GOP, as an open seat.

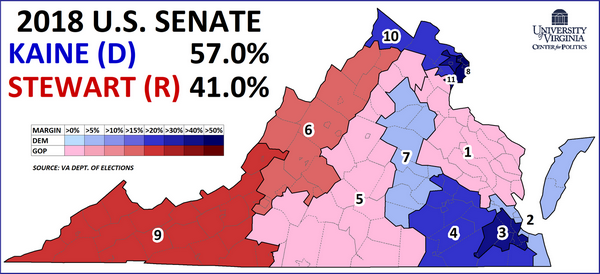

For 2018, voters appeared to be in much more of a straight-ticket mood. In the Senate contest that year, Kaine won reelection by 16%, and carried seven of the 11 districts (Map 2). All seven of Kaine’s districts elected Democrats to the House, while the four he lost remained in GOP hands.

Map 2: 2018 Virginia Senate race

With Trump as the face of the national Republican Party, both Comstock and Taylor saw much of their crossover vote evaporate, and Kaine’s margin was enough to lift Democrat Abigail Spanberger in the Richmond-centric 7th District. The Crystal Ball rates Democrats as at least slight favorites to hold the seven seats they won in 2018. If Warner can expand on Kaine’s margin — something polling suggests is possible — it would likely help Democrats in the 5th District. Kaine fell just short in this geographically vast district, which includes the Crystal Ball’s home, Charlottesville. As we noted in June, the race is more competitive than it should be for the GOP.

Overall, Virginia spent only a few cycles as a key presidential swing state on its road from being reliably Republican to now, it appears, reliably Democratic.

| Tommy Dannenfelser is a University of Virginia student studying Politics and Spanish, and has interned for the Center for Politics and the Crystal Ball. Find him on Twitter @tommydannen. J. Miles Coleman is associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball. |