KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Sen. Debbie Stabenow’s (D-MI) decision to retire at the end of her term gives Democrats a liability they have not had in the last few Senate cycles: An open seat to defend in a key presidential battleground.

— They arguably have a second in Arizona, too, given Sen. Kyrsten Sinema’s decision to become an independent and the likelihood of Democrats nominating a credible alternative to Sinema.

— Retirements are arguably easier to mitigate than they used to be because of the growing correlation between presidential and down-ballot results. But retirements can have ripple effects on the overall Senate battlefield.

— Democrats still start with an edge to hold Stabenow’s seat, and the burden of proof is on Republicans to produce a strong nominee after the party had an awful election in Michigan last year.

Playing defense in open seats

Last week’s retirement announcement by Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) gives Democrats a liability they really have not had in the last 3 Senate election cycles: An open seat in a competitive state.

In 2018, 2020, and 2022 — a full rotation of all 3 Senate classes, meaning every single seat was contested over that timeframe — only 2 Democratic senators, total, retired: Tom Udall (D-NM) in the 2020 cycle and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) last cycle. The latter is safely Democratic at the federal level and was an easy Democratic hold; the former ended up being somewhat close — now-Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) won by about a half-dozen points — but it was more of a sleeper than a hotly-contested race.

Al Franken (D-MN) did end up resigning as part of the “Me Too” reckoning in late 2017, but appointed Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN) won 2018 special and 2020 general elections for the seat by 11 and 5 points, respectively. We don’t count this (and other similar situations) as an open seat because Smith was an incumbent, albeit an appointed one.

Over the same 3-cycle timeframe, the Republicans had 12 retirements. Republicans ended up losing 2 of the subsequent open-seat elections: Arizona in 2018 and Pennsylvania last year.

Republicans also lost Alabama, for a few years, after Jeff Sessions (R-AL) resigned to become U.S. Attorney General. Doug Jones (D) won the seat in a 2017 special election but lost it in the 2020 general election to now-Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL). The appointee to the seat, Luther Strange (R), lost the nomination to former state Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore (R). Appointed incumbents Kelly Loeffler (R) and Martha McSally (R) also lost a pair of 2020 elections to Sens. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and Mark Kelly (D-AZ), respectively. Warnock and Kelly won full terms as elected incumbents against new opponents in 2022.

The last Democratic retirement in one of the core presidential swing states was way back in 2016, when then-Minority Leader Harry Reid (D) stepped aside. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) defended the seat in both 2016 and 2022 in very competitive elections.

Historically speaking, it’s actually more common for party flips in Senate races to come against incumbents than in open seats — but this is also an instance where the context matters when discussing the statistics.

In general elections held from 1954 to 2022, 147 party flips came in races where an incumbent lost, versus 76 in open seats, per the tally from Vital Statistics on Congress. So about two-thirds of the total flips in that timeframe came in incumbent-held seats.

However, remember that there are always many more seats defended by incumbents in a given year than there are open seats. On average, and since 1954, there’s been just 6 senators not seeking reelection each year compared to 28 senators who did seek reelection. So your average open seat is likelier to flip than your average incumbent-held seat, because in any given year there are far fewer of the former than the latter.

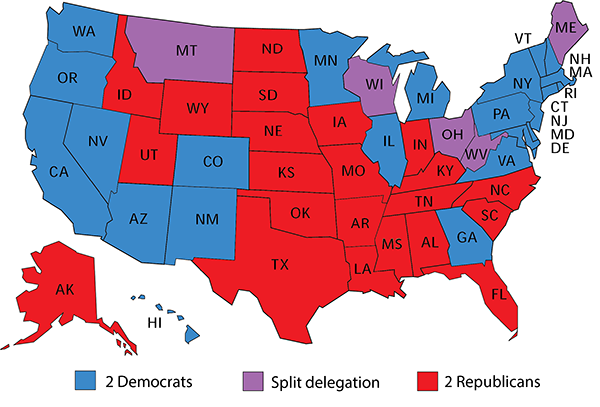

Still, this is also an era where presidential partisanship is defining Senate results more and more, which may make incumbency less important. Map 1 shows the current partisan makeup of the Senate.

Map 1: Current partisan makeup of Senate

Note: The three independents who caucus with Democrats — Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, Angus King of Maine, and Bernie Sanders of Vermont — are counted here as Democrats.

Counting the 3 independents — Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, Angus King of Maine, and Bernie Sanders of Vermont — as Democrats gives the Democrats a 51-49 majority. Only 5 of the 100 Senators represent states that their party did not win for president (again, counting the independents as Democrats): Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Ron Johnson (R-WI) are Republicans in Joe Biden-won states, while Sens. Jon Tester (D-MT), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), and Joe Manchin (D-WV) are Democrats in Donald-Trump won seats.

This helps illustrate how the power of incumbency and other localized factors are decreasing in importance. Following the 2020 election, distinguished congressional scholar Gary Jacobson found that the state-level correlation between presidential and Senate voting in that election was the highest ever.

So it may be that losing Stabenow is not that big of a deal for Senate Democrats and that retirements may not be as meaningful as they might have been in the more distant past.

However, there also are cascading campaign effects from retirements. Let’s look at 2022, on the Republican side. First off, Republicans did lose an open seat, Pennsylvania, after Sen. Pat Toomey (R) retired. Perhaps now-Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) would have beaten Toomey anyway, although the incumbent almost assuredly would have been a stronger candidate than television doctor Mehmet Oz (R), who Fetterman relentlessly mocked as an out-of-touch New Jersey transplant.

Beyond that, Republicans also had to defend open seats in competitive but GOP-leaning North Carolina and Ohio. They successfully accomplished that, but perhaps at more cost than they’d hoped, as now-Sens. Ted Budd (R-NC) and J.D. Vance (R-OH) were lapped by their opponents in fundraising. Senate Leadership Fund, the significant outside spending group connected to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), spent $70 million, combined, on just these 2 races. Perhaps the groups could have spent less if Richard Burr (R-NC) and Rob Portman (R-OH) had not retired, although it is worth noting that Burr faced insider trader accusations that likely would have been an issue in his campaign (late last week, Burr said the Securities and Exchange Commission ended its investigation into him). Might that money have made a difference elsewhere? Maybe, although Nevada was the only Senate race that Republicans lost that was extremely close (it was decided by a little less than a point). But SLF spent about $25 million there anyway, and Nevada is a much smaller state than Ohio and North Carolina.

Retirements could also have an impact on who decides to run. For instance, both Toomey and Portman announced their retirements very early — Toomey a month before the 2020 election, and Portman in late January 2021. Would the eventual Democratic nominees in those races have run anyway against the incumbents? Quite possibly, particularly in the case of Fetterman, who had already run in the primary for the right to challenge Toomey in 2016. But it’s hard to know definitively. It’s also impossible to know if the retired Senate incumbents would have been easily renominated, or if they would have been credibly challenged in a primary.

There are a ton of what ifs here, but the overall point is this: Incumbents do bring some advantages, typically at least in terms of resources, that challengers and/or potential replacements do not necessarily possess at the start of their campaigns. Although even that is not always the case, as there have been some instances where a retirement has actually benefited the incumbent party. In 2010, then-Sen. Chris Dodd (D-CT), trailing in polls, stepped aside for popular state Attorney General Richard Blumenthal (D), who won the seat despite a controversy over misrepresenting his military service. But those cases are the exceptions, and retirements sometimes have ripple effects on the overall Senate map, even if the incumbent party defends the specific open seat in question. So retirements are worth watching as we see how the 2024 map develops — particularly in the most vulnerable Democratic seats, Montana, Ohio, and West Virginia (Brown in Ohio has already said he will run, while Montana’s Tester and West Virginia’s Manchin have not revealed their 2024 plans).

In addition to Michigan, Democrats have another quasi-open seat to defend: Arizona — unless Democrats decide to give now-independent Sen. Sinema a pass and support her as an independent against the eventual Republican nominee. But the state Democratic Party is not exactly rushing to back her, and Rep. Ruben Gallego (D, AZ-3) appears to already be gearing up to run. Gallego recently released an internal poll showing him at 40%, 2022 gubernatorial nominee Kari Lake (R) at 41%, and Sinema way back at 13%. (We assume Lake was included here as effectively a Republican placeholder, although she may be considering the race.) While we offer our usual caveat that internal polls typically get released for a reason, we do find it believable that Sinema, whose approval numbers have been poor, could end up in a distant third place if she runs for reelection as an independent. The point here is that Democrats may not have an incumbent to support in Arizona, either, whatever Sinema’s ultimate decision on running ends up being.

As for Michigan itself, Democrats did recapture it at the presidential level in 2020 after Trump won a shocking victory there in 2016. Biden carried it by a little under 3 percentage points. While midterms do not carry much if any predictive value for a subsequent presidential election, Democrats had a smashingly successful election in the Wolverine State in 2022, retaining all the elected statewide executive offices and flipping both chambers of the state legislature. They were assisted by a very weak slate of Republican opponents; a new redistricting system that created fairer maps than previous Republican gerrymanders; and a statewide ballot issue on abortion rights where the “yes” side performed a bit better than Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D-MI) did in her 11-point reelection victory.

The Democrats’ recent success in Michigan has also given them a clearer bench of contenders for this open Senate seat. The one who seems the most likely to run, at least according to reporting in the aftermath of Stabenow’s announcement, is Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D, MI-7). She has performed well in 3 elections in a district that, in a couple of different iterations, voted both barely for Trump in 2020 (the old MI-8 she won in 2018 and 2020) and then barely for Biden (the new MI-7 she won in 2022). Trying to move up to the Senate makes a lot of sense for Slotkin, as the state as a whole is a bit bluer than her Lansing-centered district. Stlokin’s MI-7 is also a successor to the district that Stabenow represented for 2 terms in the 1990s. When Stabenow made the jump to the Senate, her House seat flipped, so Democrats would have to work to hold Slotkin’s seat.

Several other leading Democrats have already suggested they will not run, like Whitmer, but others who might be considering the race are Reps. Debbie Dingell (D, MI-6) and Haley Stevens (D, MI-11), Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist (D), and state Sen. Mallory McMorrow (D), among others.

On the Republican side, a potential credible contender, former Rep. Candice Miller (R), quickly said no. Two-time Senate candidate John James (R) — who lost by 6.5 and then 1.7 points in 2018 and 2020, respectively — was just elected to the House by a closer-than-expected margin in November. He didn’t really say yes or no when asked about running for Senate. Former Rep. Peter Meijer (R, MI-3), who lost a close primary last year after backing the second impeachment of Donald Trump, offered a “no comment” when asked. James or Meijer could be strong Republican contenders, although it may not be a great look for James to run for the third time in four cycles, and Meijer likely would have trouble getting nominated (but would probably be a good general election contender if he could). There are also some of the 2022 also-rans who could potentially run, like gubernatorial nominee Tudor Dixon (R), although Democrats likely would not fear those candidates.

Overall, Democrats have won 15 of the last 16 Senate elections in Michigan, with the only exception coming in 1994, when Spencer Abraham (R) won an open seat after the retirement of 3-term Sen. Donald Riegle (D). Riegle, whose victory started the 15 in 16 streak, first won in 1976 after earlier switching from Republican to Democrat as a member of the House. Stabenow beat Abraham in a close 2000 election and has held the seat ever since. Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI) held the state’s other seat from 1979-2015 and was replaced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI). Peters, who had a successful run as chairman of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee last cycle, announced Monday he was staying in the job.

At this particular point, we look at Michigan as being to Republicans what North Carolina is to Democrats. What we mean by that is that both are highly competitive, but in federal races, one side usually has an advantage — in North Carolina, that’s Republicans, and in Michigan, that’s Democrats. We have not released formal Senate ratings yet this year, but we don’t think we are going to list Michigan as a Toss-up, although it’s possible it will get there later in the cycle. But Democrats have an edge to start.