| Dear Readers: This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, which features short updates on elections and politics.

— The Editors |

The end of era in Alaska

Late last Friday, some unfortunate political news broke: while he was on a flight back home, the Dean of the House, Rep. Don Young (R, AK-AL) passed away. Earlier this month, the octogenarian Young marked 49 years in the House — this made him its longest-serving Republican member ever, and the 6th-longest serving member overall in the chamber’s history.

Though Young would have turned 89 this summer, he kept a brisk schedule and was an active legislator. Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he introduced legislation aimed at seizing the assets of Russian oligarchs. Even as Young made a habit of criticizing environmentalists, by the time of his death, he was one of the more moderate Republicans in the conference: he voted for President Biden’s infrastructure package and was a strong proponent of looser marijuana laws.

While the Last Frontier could see a chaotic election season this year, one certainty seems to be that whoever is ultimately elected will have a hard time replacing the colorful Young.

As it has been almost 50 years since Alaska last saw a special election, some history is in order.

In 1972, when Young was a state legislator representing Fort Yukon, he was the GOP nominee against then-Rep. Nick Begich (D, AK-AL). A few weeks before the 1972 general election though, Begich, along with then-House Majority Leader Hale Boggs (who was in the state on a campaign trip), boarded a famously ill-fated airplane — they disappeared on Oct. 16, and were declared dead in December. Though Alaska was among the 49 states that Richard Nixon carried in his landslide reelection that year, Begich was reelected in absentia.

When Begich’s seat was declared vacant, Young was well-positioned to make another run. He won the ensuing March 1973 special election by just under 3 percentage points. In that election, the candidates were selected by the state parties: while the state Republicans unanimously nominated Young, Alaska Federation of Natives president Emil Notti emerged from a contested Democratic convention.

This year, the special election will be held under a completely different format. In 2020, Alaska voters narrowly approved a ballot measure that shifted the state’s election system to a ranked choice format — although there is a twist. Under the new system, all candidates, regardless of party, run on a primary ballot, where voters may only select a single candidate. The top 4 finishers then advance to a general election, where voters will rank their choices.

According to state elections officials, the special primary seems set for June 11. The special general election will coincide with the regular primary, on Aug. 16 — the former will be ranked choice while the latter will not be. Finally, the regular general election (where voters will rank 4 candidates) will be in November.

It is important to keep in mind that Alaska is having 2 elections for its sole House seat this year, and that, given the uncertainty that comes with this new format, it is possible that the winner of the special contest may not be the winner of the regular election.

Both elections have the potential to be crowded. Even before Young’s death, he drew a notable intraparty opponent in Nick Begich III, the grandson of the man he replaced. Though she has seemingly taken less concrete steps towards running, former governor and 2008 GOP vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin has not ruled out seeking the seat. Anchorage Assemblyman Chris Constant is the only announced Democrat, although 2020 Senate candidate Al Gross seems likely to enter. Gross lost to Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK) 2 years ago — though he campaigned as an independent, Gross ran with the Democratic nomination.

While the field could still grow in the coming weeks, we are starting the race off as Likely Republican. Though Republicans are ordinarily strong favorites in Alaska, as the saying goes, special elections are, well, special — and this is before even considering that the special election will be the first statewide contest conducted under the new rules.

As an aside, and though they had a warm relationship, Young’s absence may work in favor of Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), who is seeking a 4th full term this year: with nearly 20 years in office, she is now the most senior member of the delegation — potentially an important selling point, given Alaska’s relationship to the federal government.

Republicans’ state legislative dominance

It is a common complaint among Democrats that, in recent years, Republicans have done a better job prioritizing and winning state legislative races. That certainly shows in the recent results.

The States Project, a progressive group that supports Democratic state legislative candidates, recently released a survey from the progressive pollster Data for Progress that showed Democrats are likelier than Republicans to believe that Congress, rather than state legislatures, are the major battlefield for deciding certain key, divisive issues, per Reid Wilson’s recent piece on the polling in The Hill. This difference in focus among partisans may say something about the Republicans’ relative success in state legislative races since 2010, when Republicans took a big advantage in state legislative control that they have continued to hold.

The 2020 elections provided a reminder of Republican state legislative dominance, as Republicans held all of their state legislative chambers and surprisingly flipped 2 Democratic-held ones, the state House and Senate in New Hampshire. This came despite losing control of both the presidency and the Senate. Last November, Republicans flipped the Virginia House of Delegates, giving them control of another chamber in a state that voted for Joe Biden in 2020.

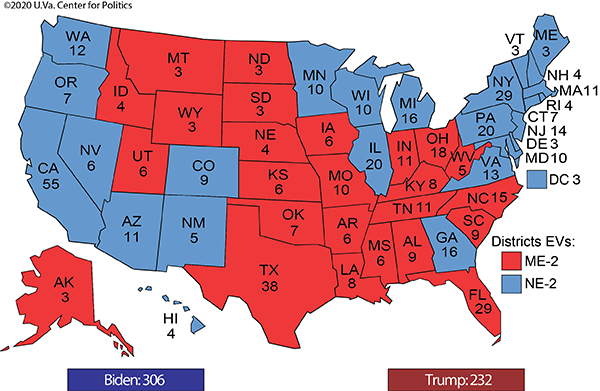

How dominant are Republicans? Let’s compare 2 maps. Map 1 shows the 2020 Electoral College results.

Map 1: 2020 presidential election

Biden won 25 states plus the District of Columbia in victory, while Donald Trump won 25 states in defeat.

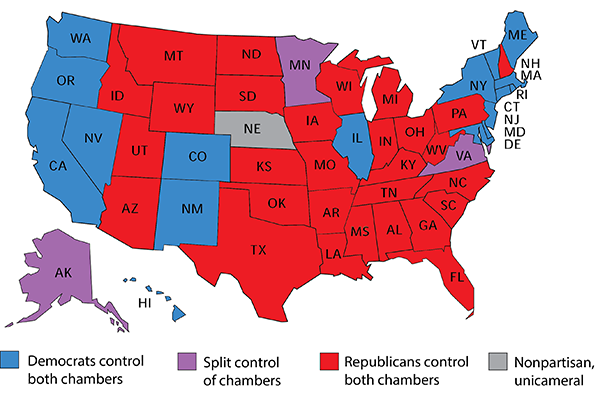

Map 2 shows the current party control of state legislative chambers.

Map 2: Current party control of state legislatures

Now, look at Map 1 and then Map 2. Notice something? The Democrats do not control a single chamber in a state that Donald Trump won with the debatable exception of Alaska’s state House, where Republicans have a majority of members, but a coalition of Democrats, independents, and Republicans elected the chamber’s speaker. Meanwhile, Republicans hold both chambers in 6 Biden-won states (Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) and a single chamber in 2 others, Minnesota and Virginia, for a total of 14 Biden-state chambers. Overall, Republicans hold 61 chambers — 62 if one includes Nebraska’s technically nonpartisan but functionally Republican unicameral state legislature — while Democrats hold 36, with Alaska’s House not counted in either side’s tally.

In addition to holding many Biden-state legislative chambers, the Republicans also have done a better job winning in hostile districts recently. CNalysis tracks state legislative elections and has computed the number of Biden-district Republicans and Trump-district Democrats among the more than 7,000 state legislators elected across the nation. According to Chaz Nuttycombe of CNalysis, there are a little more than double the number of Biden-district Republicans (about 400) compared to Trump-district Democrats (about 170). One would expect this disparity to increase in 2022 given what appears to be a strong Republican electoral environment, and Republicans could cut more deeply into Biden-state legislative chambers as well.

Reasonable people can debate the main reasons for the Republican edge in state legislative control — political realignment, gerrymandering, greater Republican attention to the races, or other factors — but the fact of it remains.