|

Dear Readers: Join us today at 2 p.m., just hours before the final presidential debate, for the latest edition of Sabato’s Crystal Ball: America Votes. Professor Sabato will be joined by Tara Setmayer, who is serving as a resident scholar at the Center. We’ll also hear from former White House Counsel John Dean, and former Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL). If you have questions you would like us to answer about the closing days of the campaign, email us at [email protected]. Additionally, an audio-only podcast version of the webinar is now available at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast providers. Search “Sabato’s Crystal Ball” to find it. You can watch live at our YouTube channel (UVACFP), as well as at this direct YouTube link. One other note: The Center for Politics’ new three-part documentary on the challenges facing democracy, Dismantling Democracy, is now available on Amazon Prime. This week, we continue with our States of Play series. Matthew Isbell, who regularly writes about Florida elections, will explore the electoral trends in this quintessential swing state. This is our sixth installment of our detailed look at the key states of the Electoral College; previous editions featured Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Ohio. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— While it is a swing state, expect Florida to vote to the right of the national popular vote.

— Biden is likely to underperform Hillary Clinton in Miami-Dade, but outshine her in working class communities and suburbs.

— How Florida’s seniors judge Trump on COVID will likely decide the state.

Florida, Florida, Florida

As we head toward the end of another presidential election, Florida continues its role as a major battleground. Florida is a critical state for Donald Trump this year, as any victory for him almost certainly requires the state’s 29 electoral votes. In 2016, Trump trailed in most Florida October polls but the final averages showed him narrowly polling ahead. He would go on to take the state by 1.2%. While Barack Obama won Florida in 2008 and 2012, both these wins were by smaller margins than his nationwide average. Indeed, despite being a “swing state,” the state’s margins have been on average three points better for the GOP than the national popular vote.

The narrow Republican advantage in Florida is thanks to a more reliable voting coalition.

The heart of the modern GOP base in Florida is rural whites, Midwestern retirees, and Cuban exiles. All three of these groups have extremely high voting propensity. The democratic base is Black, non-Cuban Hispanic, and younger voters. All three of these voting blocs have seen turnout struggles in the past. Republicans operate at an advantage because they can focus on persuasion to swing voters and their rock-solid base will always show up. Democratic campaigns in Florida are a complex amalgamation of persuasion and turnout. A good metaphor is that both parties have to walk up a steep hill, but the Democratic walker has 50-pound weights in their backpack. This has allowed the Republicans to maintain a modest advantage in the state. Obama’s wins were widely credited to his well-funded and well-organized machine. Without that organization, Florida Democrats have struggled.

The changing coalitions behind Trump’s 2016 win

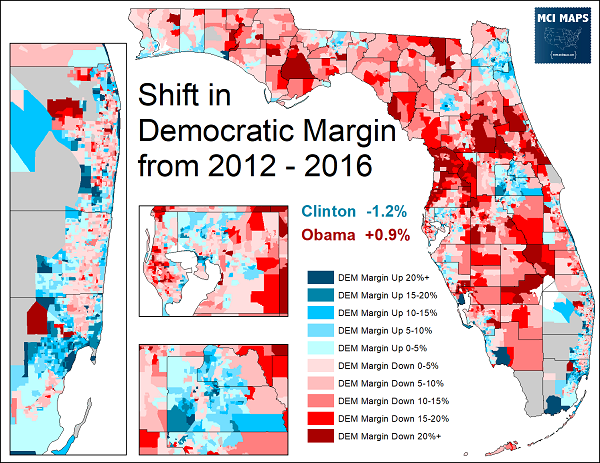

Donald Trump’s 2016 win in Florida did not come with a uniform right-wing swing across the state. Like much of the nation, Florida has seen its rural whites become steadfast Republicans while its suburbs and cities become more Democratic. When Donald Trump flipped the state to the GOP in 2016, he did so by making gains with rural and working-class whites and despite losing ground in suburbs, and with Hispanic communities.

Map 1: 2012 – 2016 change in Florida

A swing state with polarized counties

Florida has retained its reputation as a close state despite seeing massive changes internally. On top of shifting voter patterns, immigration into the state has consistently balanced out. For example, the state’s growing and Democratic-leaning Puerto Rican population has been balanced out by growth in GOP-leaning Midwest retirees. All this has led to Florida being a state with few “swing counties” despite being consistently close at the top of the ticket. In the 1990s, Florida had over 15 counties decided by 5% or less. By 2016, it was down to four. A vast majority of counties moved to the right, but the handful of left-moving areas included the heavy population centers like Orange (Orlando), Miami-Dade, and Hillsborough (Tampa).

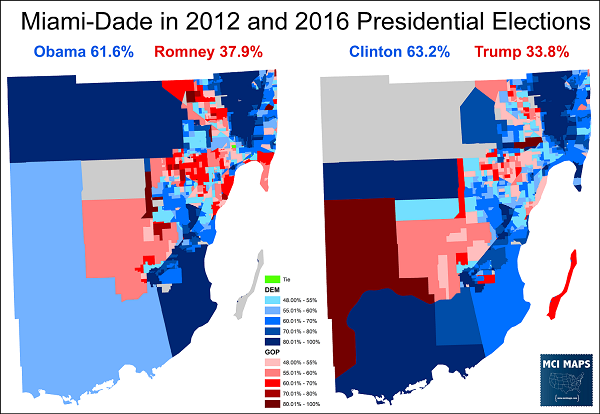

Make or break in Miami-Dade

Miami-Dade is a world of its own in Florida: a voter-heavy region with a mixture of cultures that is impossible to summarize. The county is home to Cuban exiles, Blacks, Caribbean immigrants, retirees, wealthy condo communities, densely packed suburbs, and the outskirts of the Everglades. For many years, the Cuban exile community was a major GOP staple in the county. However, the community’s right-wing bent has weakened as a newer generation grows up and is less cautious of left-wing policies. Democrats have been slowly expanding their margins in Miami-Dade with each election. In 2016, Trump’s problems with Hispanic voters were combined with Democratic growth in the Cuban community and resulted in Clinton getting a massive 29-point margin in Miami-Dade. The biggest shifts came in Cuban and non-Cuban Hispanic regions.

Map 2: Miami-Dade County in 2012 and 2016

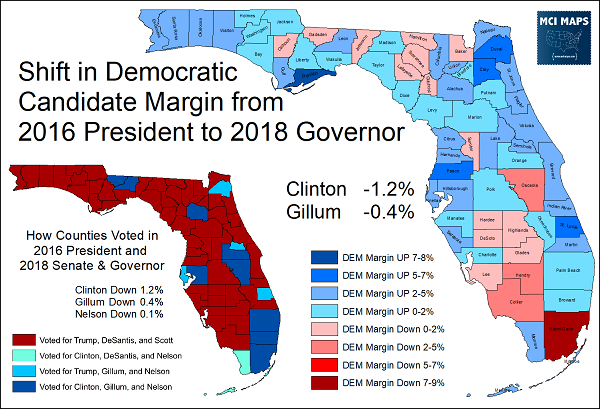

Then came the 2018 midterms, which saw Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL) and Democratic gubernatorial nominee Andrew Gillum narrowly lose statewide contests despite a Democratic wave occurring in much of the country. Nelson and Gillum flipped several counties that Trump had won in 2016. Democrats took back working-class Pinellas (St. Petersburg/Clearwater) and St Lucie while also flipping longtime-GOP Duval (Jacksonville) and Seminole (Sanford). Yet they still came up short. A major culprit? A large swing to the right in Miami-Dade.

Map 3: Hillary Clinton 2016 vs. Andrew Gillum 2018

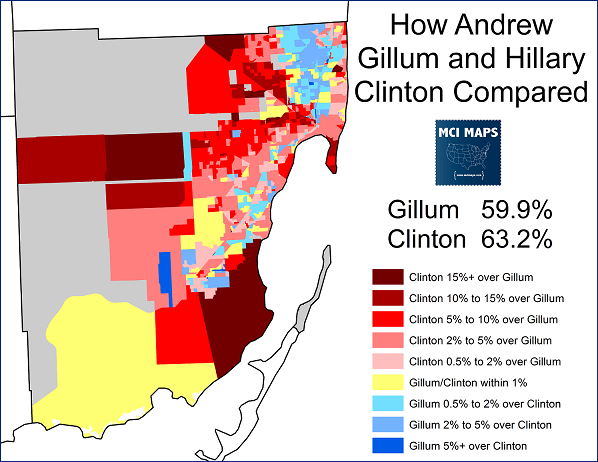

Map 4: Clinton vs. Gillum in Miami-Dade County

As 2020 approaches, Democratic heartburn about Miami-Dade and Hispanic voters had resurfaced. Some polls have shown conflicting results, but a consensus is that Biden is not getting the same Hispanic margins as Clinton got in 2016. The drop in Hispanic support coincides with more local Cuban and non-Cuban Hispanic Republican politicians coming out more forcefully for Trump this time than they did in 2016. The main tagline against Biden and the Democrats is the socialism line — and the problems in Venezuela have been used as a main talking point. However, the same pollsters who show Biden under-performing with Hispanics point out he can make gains thanks to growth in the non-Cuban share of the Hispanic population as more migrants from Central and South America enter Florida.

To counter a potential decline with Hispanic voters, the Biden campaign is hoping to galvanize increased Black turnout. Kamala Harris has been a major asset in this effort, as reports on the ground in Florida show her selection as VP has galvanized the Black and especially Caribbean-American communities. Democratic victory likely relies on getting the tens of thousands of Black voters who didn’t vote in 2016 to return to the polling station this go around. It should be no surprise that the Biden campaign just did an event in Miramar as part of an effort to court Caribbean voters.

Suburbs, working-class whites, and seniors

When Trump won in 2016, it was his strength in the Rust Belt of America that secured him the Electoral College. In Florida, this strength with working-class whites was seen across the state. However, in 2020 this voting block is still very much up for grabs. A longtime logic for nominating Biden was his appeal with working-class white voters. In Florida polls, this logic seems to be holding water. The Biden campaign also appears to be performing much stronger with white working-class voters than Hillary Clinton did. A recent poll out of working-class Pinellas County, which backed Obama and Trump, gives Biden with a 13% lead. Biden is also outperforming Hillary Clinton by 10 points in HD36, a working-class district in Pasco County. The 36th became a staple for the Trump surge with working-class voters when the district went from voting Obama to voting Trump by 20% — this represented the largest swing from 2012 in the state. The recent HD36 poll has Trump up by only 10 points, far below his 2016 margin.

The suburban swing to the left in Florida is the same story we have seen across Florida. It began in earnest in 2018 when Democrats flipped Seminole and Duval counties and made several gains in suburban state house seats. Democrats easily flipped four house districts in the Tampa and Orlando suburbs in 2018. This suburban swing appears to have continued into 2020. A recent poll out of HD60, which covers the coastal upper-income suburbs of Tampa Bay, shows Biden leading by 7% and the GOP incumbent losing re-election. This district had narrowly backed Trump in 2016. Meanwhile, a poll out of HD89, which is the coastal and southern Boca region of Palm Beach, has Trump losing by 14%; a 13-point swing from 2016. These individual polls out of suburbia show a continued blue wave that began in 2016.

The senior vote is always a critical vote in any Florida election. The state has been a retiree destination for decades — and this reputation has not abated. It is important to note how distinct the assorted retiree communities are. The Villages garnered national attention in recent years for its size and being a GOP destination. However, older communities based in south Florida are much more Democratic. The retiree and condo communities of southeast Florida are still heavily dominated by former residents of New England and the NYC metro area. In the 1970s, Miami Beach was a big destination for New York Jewish retirees. However, Broward and Palm Beach have surpassed Miami in recent decades. These voters are much more Democratic up and down ballot. Places like the Wynmoor Condo Community or Kings Point have been major campaign stops for Democratic politicians. Meanwhile, 250 miles northwest, the Villages is a must-visit for any aspiring GOP politician. The Villages has become so prominent because of its size. Many of the southeast communities are more scattered. The Villages is a dense older-living community lodged in northeast Sumter County that only continues to grow.

Overall, the Florida senior vote leans Republican. But the coronavirus pandemic has put Trump on the defense with many of these voters. Democratic seniors in places like the Villages have become more outspoken, prompting well-documented clashes between supporters of both camps. How the final senior vote breaks down isn’t clear yet (with conflicting statewide polls) — but considering how reliable they are at voting, seniors are a critical group. If Biden can narrow the gap, it could pay dividends. If Trump can hold this group, it could save him.

Campaign structure and COVID

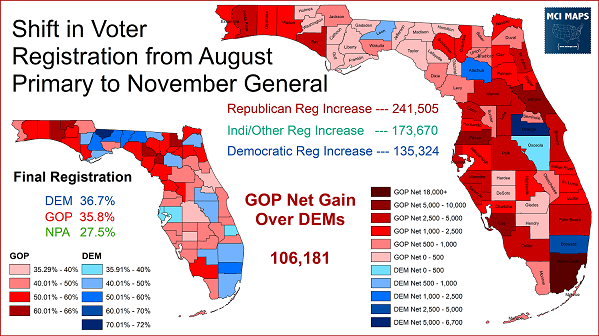

Campaigning in Florida has been unique this year thanks to the coronavirus pandemic. In-person events are rare and canvassing door to door greatly varies by region. However, this has not been equal across the state. For much of the last few months, the Republicans have been much more aggressive in campaign efforts. These included door to door canvassing and registration drives. This has run counter to Democrats focusing on digital and texting outreach. Democrats have focused on signing voters up for vote by mail and banking in their votes well before election day. But many Democrats have expressed concern at the lack of in-person campaigning. Meanwhile, the Republicans, for weeks, have been talking about all the new voters they were registering.

This boasting by the GOP revealed itself when the final registration report was released. It showed that since the August primary, the Republicans registered 106,000 more voters than the Democrats.

Map 5: 2020 voter registration shift in Florida

Congressional battlegrounds

Florida’s congressional map was redrawn in 2015 after court cases struck down the original plan. The latest map is representative of the state, and the 13 districts Democrats hold all voted for Hillary Clinton while Republicans hold the 14 Trump districts. Heading into November, only a few districts have the potential of flipping.

The most vulnerable Democratic seat is in the Miami-Dade-based 26th District, which Debbie Mucarsel-Powell (D, FL-26) won by 2% in 2018. Mucarsel-Powell pulled off a bit of an upset when she ousted Republican incumbent Carlos Curbelo. The GOP scored a major victory when they recruited outgoing Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez to run. While this district backed Clinton by 16 points, the region’s ticket-splitting is a major boost to GOP efforts. Curbelo himself had won reelection while Trump lost his seat in 2016, and even in his loss, he outperformed the statewide Republican candidates.

For the Republicans, their most vulnerable seat is the 15th District, which stretches from east Hillsborough and into Polk and Lake counties. While the district votes to the right of the state, giving Trump a 53%-43% win, the eastern Hillsborough region is growing in population and in Democratic share. Republicans were already worried that first-term Rep. Ross Spano (R, FL-15), dogged by campaign finance violations, would lose the seat in November. Spano would go on to lose his primary to Lakeland City Commissioner Scott Franklin — whose dominance in his Polk base propelled him to victory. Franklin is considered a modest favorite to hold the seat.

Conclusion

Like every presidential election, expect Florida to be a close contest on Election Night. Democrats are likely to start the night with a big lead thanks to vote by mail being reported first, and the march will be on to see if the Republicans can close the gap.

It is important for all watching that it isn’t just about who wins a county — but what the margin looks like. A bad Miami-Dade margin could be fatal for Biden. Meanwhile, if Trump is losing big in places like Pinellas or Seminole, he will be in bad shape.

We should expect some of these counties to move independent of each other due to their unique demographics.

Election night in Florida can be akin to a roller coaster as one county delivers good news and another bad news regardless of which side you are on.

Expect a similarly bumpy ride this year.

| Matthew Isbell has been writing about Florida politics since 2011. He does data consulting for campaigns and political committees of all types, but primarily for Democrats. His Twitter handle is @mcimaps. |