| Dear Readers: This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, featuring short updates on elections and politics. First, Managing Editor Kyle Kondik assesses the latest round of House retirements and how this year’s number of incumbents running compares to recent history. Then, Contributing Editor Carah Ong Whaley surveys the public’s growing concerns about the state of American democracy.

— The Editors |

Tallying House retirements so far

Table 1: Crystal Ball House rating change

Four more House retirements over the past several days pushed the number of incumbents running this year down to the post-World War II average, and there is of course more time for other House incumbents to retire.

Four Republicans—Reps. Doug Lamborn (R, CO-5), Greg Pence (R, IN-6), Larry Bucshon (R, IN-8), and Blaine Luetkemeyer (R, MO-3)—joined the growing number of House members heading for the exits recently. Their retirement announcements mean that, as of now, 22 Democratic House members and 16 Republicans are not running for reelection, according to the House of Representatives Press Gallery.

That leaves, at maximum, 397 House incumbents running for another term this year—that assumes no more House retirements (which is not a safe assumption) and that the new members eventually elected in special elections to a few remaining vacant seats decide to run for reelection to full terms.

According to Vital Statistics on Congress as well as our own calculations, an average of 397 incumbents have run for reelection to the House each two-year cycle since 1946—the same number of incumbents who appear to be running again at the moment. The number of incumbents running again may be slightly different than the number of open seats, as sometimes two members will run against each other in the same district because of redistricting. There’s at least one such instance this cycle, as a court-imposed new map in Alabama pushed Republican Reps. Jerry Carl and Barry Moore to run against one another in AL-1, leaving the redrawn AL-2 as an open seat (and Likely Democratic pickup) thanks to the new lines. It is possible that looming new maps in Louisiana and New York could create similar situations—or lead to additional retirements.

That a little under 400 House members on average seek reelection each cycle in a 435-member chamber just underscores the reality that despite high incumbent reelection rates, there actually is a fair amount of turnover in the House from each cycle. Another statistic that shows this trend is that following Bucshon’s retirement, at most just 10 of the 66 Republicans who flipped Democratic-held districts in the GOP’s 2010 wave will be in the House come 2025.

Bucshon, one of the recent retirees, represents the so-called “Bloody 8th,” a one-time competitive district in southwest Indiana that has become a Republican bastion as Democrats have lost ground among the working-class white voters who dominate that district. The district was home to a high-profile controversy in the 1984 election, in which the Democratic-controlled House eventually determined Democratic incumbent Frank McCloskey won by just four votes, effectively overruling state authorities to howls of protest from Republicans who believed that Democrats stole the seat (for more on the 1984 race and its lingering repercussions, see this great piece from Politico Magazine’s Michael Kruse). The current IN-8 gave nearly two-thirds of its votes to Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election and remains Safe Republican in our ratings.

Trump won 62% of the vote in the retiring Blaine Luetkemeyer’s MO-3, which extends from central Missouri to the St. Louis exurbs, and he got 65% in the retiring Greg Pence’s IN-6, which contains a southern chunk of Democratic Indianapolis’s Marion County and extends east to the Ohio border, taking in many red counties along the way. These districts are also much too Republican to elect Democrats. Pence, the brother of former Vice President Mike Pence (R), is the fourth Indiana Republican not seeking reelection to the House this year: In addition to Pence and Bucshon, Rep. Jim Banks (R, IN-3) is running for Senate and Rep. Victoria Spartz (R, IN-5) is retiring, although she has sometimes waffled on that decision.

Alone among the four newly-open Republican seats, the district held by Doug Lamborn, CO-5, does merit a bit of a look as a district that could potentially be competitive in a general election. We’re actually going to move it from Safe Republican to Likely Republican in our ratings, even though Democrats would need to have a whole lot to go right to seriously contest it.

Colorado Springs, described by the Almanac of American Politics as “one of America’s most Republican metropolitan areas,” makes up the core of CO-5, which has consistently elected Republican House members since its creation after the 1970 census. The fast-growing city and surrounding areas are home to the Air Force Academy and otherwise features a huge military presence. Lamborn had some primary trouble over the years, but was always renominated since replacing the retiring Joel Hefley in 2006 (Lamborn beat Hefley’s preferred successor, outflanking the former Hefley aide to the right). The growth of Colorado Spring’s El Paso County, in addition to an added House seat in Colorado, meant that CO-5 could be drawn to just cover almost all of El Paso County, dropping a few rural counties that had previously been in the district.

As recently as 2016, Donald Trump was winning CO-5 56%-34%, but that margin dipped to 53%-43% in 2020. Trump’s 11-point margin in El Paso County was the smallest GOP margin of victory there since Barry Goldwater lost the county in 1964. So there’s some movement away from the GOP in the district even though this is still clearly Republican turf. State Republican Party Chairman Dave Williams (R), also a former state representative, unsuccessfully tried to primary Lamborn from the right last cycle. He is running again, and if nominated, Democrats might be able to argue that the election-denying Williams—who unsuccessfully tried to list his name as Dave “Let’s Go Brandon” Williams on the 2022 ballot, borrowing a negative phrase directed at President Biden—is too far right even for a right-leaning district. In 2022, GOP statewide candidates for Senate and governor carried the district by 8 and 3 points, respectively; in that same election, Lamborn won 56%-40% over a Democrat, although that was his lowest vote share in a general election.

Anyway, the district merits watching as a deep sleeper now that it is an open seat and given some of the slight Republican erosion there.

Colorado’s three current Republican-held districts are now at least sort of open seats: Reps. Ken Buck (R, CO-4) and Lamborn are retiring, and Rep. Lauren Boebert (R, CO-3) is leaving her more competitive district behind to run in the reddest district in the state, CO-4. We now rate the three districts as Leans Republican (CO-3), Likely Republican (CO-5), and Safe Republican (CO-4).

Meanwhile, we continue to await additional House retirements. The postwar record is just 368 incumbents running for reelection in 1992, so this year is not going to match that, but we do expect the retirement tally to increase—maybe even by the time you read this, given the several announcements we have seen lately.

What the public thinks about democracy

For over a decade now, scholars have been warning about democratic backsliding, and a review of high-quality surveys from 2023 finds that concern about the state of democracy is now top of mind for most Americans across the political spectrum. There’s also a little silver in that grey lining—while still troubling, only a minority (1 in 5 across multiple surveys) favors some alternative form of government and support for democracy is higher now than it was a few years ago.

The challenges for democracy are rooted in different issues that impact people’s lives in a diverse and complex country: divergent lived experiences based on peak levels of socioeconomic and political inequality and the real and perceived lack of responsiveness of political institutions to people’s needs on those issues; the growth of pernicious polarization (when political polarization is hostile) that threatens to unravel electoral and institutional processes at every level of government; and the efforts by a few individuals to seize on divisions to gain power and work around political institutions. Since 2010, state legislatures have passed laws making it harder to vote, with access to the ballot increasingly dependent on the partisanship of the state legislature. There’s also been a rise in the politicization of election administration and extreme partisan and racial gerrymandering. Meanwhile, substantial dysfunction and hyperpartisanship in Congress, concerns over the impartiality of the judiciary, and little accountability and oversight of the executive branch have contributed to the loss of institutional capacity to address pressing public problems and declining public confidence in political institutions.

Democracy comes from the Greek words “demos,” meaning people, and “kratos,” meaning power. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, democracy is defined as a “government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections.” From a normative perspective, democracy should be how we make collective decisions over highly contested issues. However, persistent contestation over who is and who should be included in political and decision-making processes remains a challenge for multiracial democracy. Furthermore, the sorting and realignment of political parties have contributed to widening gaps between the parties on what issues to prioritize and the divisions between the parties on those issues.

Examining American National Election Studies data since 2004, there is a notable shift towards greater dissatisfaction with how democracy is working from 2012 onwards, and 2020 stands out with heightened levels of both “Very Satisfied” and “Not at All Satisfied” across demographic subgroups by party identification, indicating an increasing polarization in responses. That year, 2020, stands out as the peak of “Not at All Satisfied” and “Not Very Satisfied” (2020 is also the most recent available ANES data on these questions). When we analyze responses by partisanship and age, partisanship and race, and partisanship and gender, partisanship and race play the most significant role in variation among responses. Perhaps not surprisingly, the trends for Black and Hispanic subgroups responding to whether democracy is working often differ from those of white subgroups within the same political affiliation, perhaps indicating their different lived experiences and differing levels of political inclusion (see Figure 1). Young people also have heightened levels of dissatisfaction, with nearly half of 18-29 year olds reporting they are “Not Very Satisfied” and “Not at All Satisfied” in 2020 compared to one-third of those 60 and older. Just 12 years earlier, only 22% of the youngest age group reported being “Not Very Satisfied” and “Not at All Satisfied.”

Figure 1: Dissatisfaction with how democracy works, by party and race

After looking at the ANES data, I reviewed and conducted a comparative analysis of seven high-quality surveys from the last six months of 2023 to see where public opinion on democracy stands at the start of 2024. There is broad agreement across the range of surveys I examined that American democracy is not working, but there are substantial differences in reasons for why democracy is not working depending on partisanship and other demographic characteristics. The survey sources on views about democracy were Pew Research Center, Gallup, PRRI, Democracy Perception Index, the Open Society Barometer, AP/NORC, and Economist/YouGov. Across all of the surveys, partisan identification impacts respondents’ views on the legitimacy and fairness of the electoral process, including perceptions of voter fraud and the effectiveness of the Electoral College. And, according to the Economist/YouGov findings, people are far more likely to trust their friends and family about election information than any other source of information, including journalists, social media, and public opinion surveys.

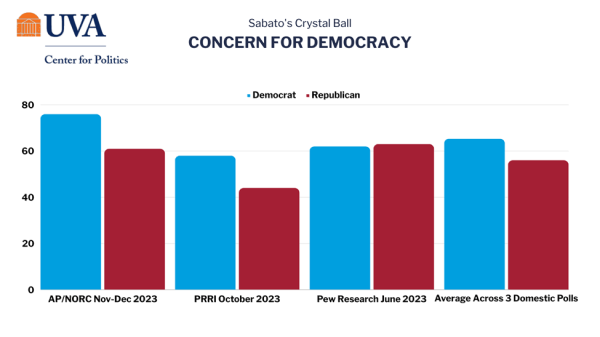

Figure 2: Majority concerned about American democracy

According to an AP/NORC survey, 51% say democracy is working “not too well” or “not well at all” and it’s related to how they view issues ranging from immigration to the economy to climate change to abortion. The 2023 PRRI American Values Survey finds that an overwhelming majority of respondents (84% of Democrats, 77% of Republicans, and 73% of independents) believe American democracy is at risk. Pew finds that a significant majority (63%) express little to no confidence in the future of the U.S. political system, with 81% of Republicans saying the system is working not too or not at all well, compared to 64% of Democrats. Older Republicans, in particular, are more likely to say the system is not working. Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to be concerned that a person’s rights and protections might vary depending on which state they are in. Conversely, a much larger share of Republicans than Democrats express concern that the federal government is doing too much on issues better left to state governments. One can see how key issues and positions from both parties can be impacting these polls: State-level protections are likely front of mind for Democrats in the wake of the Dobbs decision, which gave states much greater leeway in restricting reproductive rights, while concerns about the federal government becoming more powerful at the expense of the states is a frequent complaint from Republicans. Majorities in both parties think there is too much partisan fighting, campaigns cost too much, and lobbyists and special interests have too much say in politics. A December 2023 Economist/YouGov poll stands out for age having a greater association with views on democracy than political identity, which should set off warning bells for educators: 18-29 year olds are more closely split than older cohorts on whether democracy is no longer a viable system—31% agree and 41% disagree.

Across the surveys, many Americans believe that the federal government holds too much power, though respondents who identify as Republican and Independent are more likely to believe this than Democrats, and Republicans express greater concern about government activity when a Democrat is in office. At the same time, respondents identifying as Republican show more openness to expanding presidential power in several of the surveys, though not all. Meanwhile, Democrats across several surveys are more likely to support government-provided services now than they did before Bill Clinton was president.

Globally, there is a strong belief in the importance of democracy, but there are significant concerns about various threats to its health and effectiveness, particularly stemming from economic inequality and corruption, and concern for the role and influence of global corporations and Big Tech. In the Open Society Barometer survey of over 30,000 respondents across 30 countries, 86% want to live in a democracy and 62% report that it is preferable to any other form of government. A little more than half (54%) of American respondents to the “Democracy Perception Index” 2023 global survey gave the U.S. a rating of 7 or higher—the study’s threshold for the belief a country was democratic. American respondents listed inequality, corruption, and fear of unfair elections as principal threats to democracy, and expressed concern about disinformation and social media.

This year’s election will be another test of the limits of democracy. The AP/NORC survey highlights that the outcome of the 2024 elections influences how people feel about democracy, with significantly polarized responses: 72% of Democrats, 42% of independents, and 22% of Republicans feel democracy is broken if Donald Trump wins, compared to 64% of Republicans, 37% of independents, and 18% of Democrats if Joe Biden wins. Furthermore, 65% of respondents tell Pew that they always or often feel exhausted when thinking about politics and 55% say they are angry. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Gallup respondents currently agree with the statement that the Republican and Democratic parties do “such a poor job” of representing the American people that “a third major party is needed.” These attitudes, combined with expressed concern over the fairness of elections, could lead to people tuning out of the 2024 elections, voting in greater numbers for third party candidates, and/or skipping voting altogether.

There is some encouraging agreement on support for some political reforms. Pew finds some consensus on replacing the Electoral College with a popular vote, and majority support for term limits and age limits. Ranked-choice voting, which currently reaches 13 million voters in 51 cities, counties, and states in the U.S., is another promising reform with bipartisan support. Although there are disagreements on how to reform the system and pessimism that reforms are possible, people from across the political spectrum do want them. Furthermore, when given opportunities to engage in deliberative conversations, Republicans and Democrats move significantly toward the positions of the other party on a range of reforms. Facilitating that kind of positive interaction, though, is a huge challenge in these polarized times.