KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Monday night’s Iowa Republican caucus kicks off the presidential nominating season.

— The caucus has a spotty history of voting for the eventual nominee, particularly on the Republican side, although Donald Trump is a big favorite both in Iowa and nationally. Ron DeSantis is under the most pressure to perform, as he has basically bet his entire campaign on Iowa.

— To the extent frontrunning Donald Trump shows weakness, look for it in places like the Des Moines suburbs as well as a couple of counties with major universities.

— Meanwhile, a quartet of counties in the state’s northwestern corner should give us some indicators of where the Republicans’ strongest religious conservatives are in this race.

Looking ahead to Iowa

There is an old saying that there are “three tickets out of Iowa,” meaning that the traditional kickoff caucus doesn’t necessarily anoint the presidential nominees, but it does serve a purpose in winnowing often-bloated presidential primary fields. As we will discuss below, Iowa does indeed have a spotty record of supporting the eventual nominee, particularly on the Republican side.

It is also the case that finishing in the top three in Iowa has not been a prerequisite for winning the nomination. In recent cycles, both 2008 GOP nominee John McCain and 2020 Democratic nominee Joe Biden finished fourth in Iowa but still ended up winning their party’s respective nominations in races that ultimately were not even that close.

On Monday night, Republicans will begin the process of picking their party’s presidential nominee, and Donald Trump goes into the primary season as one of if not the most dominant non-incumbent frontrunners in any modern nominating contest. Iowa will help demonstrate whether Trump is as big of a favorite as polls make him seem.

One could argue that, in the 2024 contest, there have been three tickets into Iowa, and there may not be three tickets out. It is possible that Trump essentially has no real competition and will wipe the floor with his rivals, but to the extent he does have competitive rivals, there really are only two others: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has essentially staked his whole campaign on Iowa, and former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who has been a better fit for the more moderate and less religious New Hampshire. Haley seems likely to continue on to New Hampshire no matter what happens in Iowa; for DeSantis, finishing in third place behind Trump and Haley may not be good enough for him to justify staying in the race. There are other candidates, but entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy has not been much of factor in the race for months, and former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie dropped out on Wednesday, which is more meaningful for New Hampshire, where he was a factor, as opposed to Iowa, where he was not.

A fancy phrase we sometimes like to use is describing something as a “necessary but not sufficient” condition—meaning that winning a certain contest is a prerequisite for victory, but that win does not alone guarantee victory. For instance, in the race for the Senate this year, Republicans flipping the now-open West Virginia Senate seat is a necessary but not sufficient condition for winning the currently 51-49 Democratic Senate. If they somehow lost the race we now rate as Safe Republican, we can’t imagine them claiming a Senate majority, but they need to do more than just win West Virginia, be it claiming the vice presidential Senate tiebreaker or flipping at least one other seat while holding everything else they control.

Historically, winning Iowa has neither been necessary nor sufficient for winning either party’s presidential nomination: Many caucus winners have failed to win the nomination, and many nomination winners have failed to win Iowa.

Let’s briefly survey that history, and we’ll exclude uncompetitive nomination processes featuring an incumbent who coasted to renomination.

1972 (Democrats): “Uncommitted” technically finished ahead of frontrunning Ed Muskie, with eventual nominee George McGovern getting a major boost by finishing second behind Muskie.

1976 (Democrats and Republicans): “Uncommitted” finished first on the Democratic side again, but Jimmy Carter got the most support of the actual candidates, an important stepping stone on his road to the nomination. In a concurrently-held Republican contest that had not matured into the modern version of the caucuses we know today, unelected incumbent Gerald Ford narrowly held off Ronald Reagan in what longtime Iowa watcher David Yepsen described as “a straw poll in sample precincts [that] was taken as an early sign of Ford’s weakness as a candidate.” Ford would ultimately hold off Reagan for the nomination in a competitive contest.

1980 (Democrats and Republicans): Carter easily dispatched challenger Ted Kennedy and would win the nomination, but Kennedy’s challenge helped expose Carter’s weaknesses. George H.W. Bush narrowly upset Reagan, who would win the nomination and pick Bush as his running mate.

1984 (Democrats): Walter Mondale crushed a number of opponents, with Gary Hart finishing a distant second, but Hart got some notoriety out of the performance and ended up pushing Mondale for the nomination before ultimately losing to the former vice president.

1988 (Democrats and Republicans): Eventual nominee Michael Dukakis finished third behind Dick Gephardt and Paul Simon. Bob Dole won roughly double the support (37%) of third-place finisher Bush, but Bush would win the nomination.

1992 (Democrats): Democrats ceded Iowa to home-state favorite Tom Harkin, who was not otherwise much of a factor in the race, which Bill Clinton won. Bush, now the incumbent, was unopposed in Iowa but did show some weakness in New Hampshire; we are not including that Iowa race in our overall tally.

1996 (Republicans): Dole narrowly won Iowa en route to the nomination.

2000 (Democrats and Republicans): Al Gore beat Bill Bradley by about 25 points, presaging his sweep of the Democratic nominating season. George W. Bush won Iowa and overcame a loss in New Hampshire to comfortably win the nomination.

2004 (Democrats): John Kerry won Iowa, setting up his fairly dominant primary showing.

2008 (Democrats and Republicans): Eventual nominee Barack Obama won, while his main rival for the nomination, Hillary Clinton, finished in a competitive third. Republican nominee John McCain ignored Iowa and finished in fourth.

2012 (Republicans): Rick Santorum eventually won Iowa, but it took the state GOP more than two weeks to actually determine that he narrowly edged out Mitt Romney, who would win the nomination.

2016 (Democrats and Republicans): Hillary Clinton narrowly held off Bernie Sanders to launch what would be a harder-than-expected path to the nomination. Donald Trump skipped a late Iowa debate and finished second to Ted Cruz, but he strongly bounced back in succeeding early state races.

2020 (Democrats): Joe Biden finished fourth as part of a slow start in the early states, but he ended up winning the nomination fairly easily.

So of 11 competitive Democratic contests, the eventual nominee won Iowa 7 times (counting Carter finishing as the first named candidate behind uncommitted in 1976), while the eventual GOP nominee won just 3 of 8.

In some ways, 2024 represents a new era for Iowa, because while Republicans have kept the state at the front of their nominating process, while Democrats have relegated it in their own process.

Given Iowa’s, at best, mixed record as a predictor, it’s surprising that it took this long for one of the parties to sidestep the state. Going into the 1990s, for example, Republicans seemed to have convincing reasons to abandon it as the first contest, as it gave soon-to-be President Bush a poor showing in both the 1988 caucus and general election. But Iowa’s status on the Republican side has endured as Democrats have looked to other states. For one thing, lily white Iowa has become so unreflective of the actual Democratic primary and general electorate. The disastrous 2020 caucus, where the Associated Press was unable to declare an actual winner between Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg, likely also did not help Iowa’s standing on the Democratic side.

What to look for on Monday night

This brings us to Monday’s quickly-approaching contest, when GOP caucusgoers will venture out into sub-freezing temperatures to kick off the 2024 election. This cycle, there has been a dearth of caucus polling—perhaps with the former president being such a strong overall favorite, pollsters feel less of a need to either confirm the prevailing wisdom or to (potentially) stick their necks out.

Throughout our coverage of the Republican primary, we’ve found ourselves going back to longtime political journalist Ron Brownstein’s idea of the “wine track” vs the “beer track,” creative terms that are stand-ins for college and non-college educated voters, respectively. In addition to putting up massive leads with beer track voters, Trump has generally led his main opponents with wine track voters, although by less robust margins.

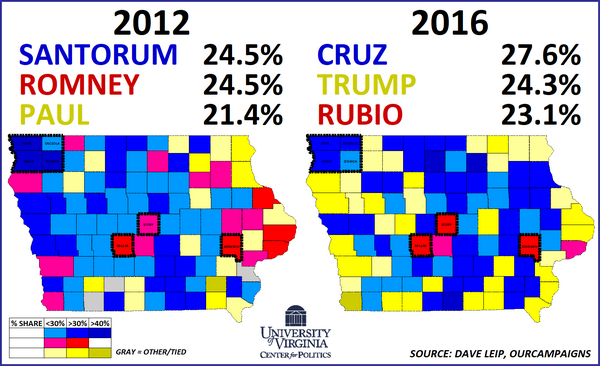

At this point, a Trump 99-county sweep seems more likely than an upset by either DeSantis or Haley. But if either of the former president’s main rivals were to make a respectable showing, where would their strength show up? Map 1, which considers the two most recent competitive Republican caucuses, may give us some hints.

Map 1: 2012 and 2016 Iowa Republican caucuses

Johnson County, home to the University of Iowa, seems the likeliest county to go for a non-Trump candidate. Johnson County is also, not coincidentally, the most college-educated county in the state, with a little over half of residents over 25 having a college degree, and it has a strong Democratic lean in general elections. Because of these attributes, in past GOP caucuses, it has also had a contrarian streak: 2000 was the most recent contested caucus where it voted with the winner. In 2008, 2012, and 2016, it broke against the statewide result in favor of a wine track-backed candidate—it backed Romney in the first two instances, and Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) in 2016. Johnson County’s outlier status also shows up in general elections: It was the only county that popular Sen. Chuck Grassley (R) lost in his 2010 and 2016 landslides, and, more recently, it was his worst county in his closer 2022 reelection campaign. Essentially, Johnson County’s demographics have made it an increasingly poor fit for a Trump-dominated Republican Party.

For similar reasons, we’ll be watching Dallas and Story counties, which are immediately west and north of Des Moines’s Polk County, respectively. The former is quickly filling up with suburbanites while the latter is another university county (home of Iowa State University) that hosted a now-defunct GOP straw poll that long had a place in Iowa caucus lore. Dallas and Story, along with Johnson, are the only three counties in the state where a majority of residents over 25 have college degrees, according to Redistricter’s data—so we’d expect the trio to serve as the backbone of any anti-Trump coalition in the state. In 2012, the list of former Sen. Rick Santorum’s 15 worst counties would have included the trio. By 2016, the three counties had fallen to appear in Trump’s bottom 10 counties (they are the three red-tinted counties on Map 1 that are noted with bolded county borders).

Northwestern Iowa is at the heart of the state’s evangelical movement, a demographic that DeSantis has heavily courted. Aside from the aforementioned metro counties, this is one area that seems like a must-win region for DeSantis, if he’s competitive statewide. In terms of its bellwether status, this region (which we are defining as Lyon, O’Brien, Osceola, and Sioux counties and is boldly outlined on Map 1 in northwest Iowa) is basically the opposite of Johnson County—the last time it did not pick the statewide winner was in 2000, when Gary Bauer, a Christian conservative activist, carried three of the four counties over Bush. Since then, this northwestern quartet has chosen the caucus winners: former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, who was also a former pastor, in 2008; then Santorum, a conservative culture warrior during his time in the Senate, in 2012; and then Cruz, who launched his campaign at the evangelical Liberty University, in 2016.

Though we’ll be watching his rivals’ showing there, we’d also note that Trump has ample room for improvement in northwestern Iowa, vis-a-vis his 2016 result. He almost certainly won’t be taking just 11% in Sioux County, for instance. In 2016, when Trump was last in a contested Iowa caucus, evangelicals still seemed to have some reservations about hitching their wagon to a reality TV show personality from New York—that group has come around to him since then, to say the least.

On the campaign trail, DeSantis has regularly brought up his endorsement from Gov. Kim Reynolds (R), who remains popular with state Republicans. If DeSantis carries, or at least comes close in Clarke County, a rural county in the south-central part of the state, it may be an indication that Reynolds has pull where she served as the elected county treasurer.

P.S. It’s not that hard to get a delegate

Democratic presidential nominating contests all have the same basic rules—delegates are awarded proportionally, and there is a 15% threshold in order to win delegates, either at the statewide or district level. Indeed, one of the things to watch in the Democratic contests is whether and where a non-Biden candidate can hit 15% and accrue some delegates. In the FiveThirtyEight national polling average of the Democratic presidential primary, Biden is at 71%, while author Marianne Williamson is at 6% and Rep. Dean Phillips (D, MN-3) is at 3%.

Republican nominating contests, meanwhile, allocate delegates in a number of different ways—presidential nomination process expert Josh Putnam has a great rundown at his invaluable FrontloadingHQ site. Of the different methods he identifies, only 11% of the delegates are awarded in a truly proportional manner (without being winner-take-most or having a winner-take-all trigger, two methods that are more common among the Republican contests). The delegates in both Iowa and New Hampshire are assigned proportionally, so they are part of that small group of truly proportional states.

There is a very low bar for getting delegates in Iowa—a candidate could get 1 of the state’s 40 delegates through winning around just 1.3% of the vote, as Putnam explains. So it’s possible that a candidate who is basically unknown nationally—like Ryan Binkley, a Texas pastor and businessman who has been campaigning heavily in the state without much apparent effect—could be represented in the delegate count.

Ultimately, the specific delegate math only becomes truly important if Trump ends up having a viable, competitive top challenger and the race drags on through the primary season. Given national and state-level polls that show Trump leading everywhere, and often by a lot, this may not be a year where the Byzantine accounting of delegates is important. Iowa will give us some indication of what kind of year it’s going to be.

We do really wonder if the weather will have some impact on the turnout and even, by extension, the results—the forecast is for unusually frigid temperatures, and there is some indication that excitement for the caucuses is not sky-high (a group from Iowa State University, writing on political scientist Seth Masket’s excellent “Tusk” Substack on the 2024 GOP race, reports that a smaller percentage of Republicans say they are definitely going to participate in the caucus than Democrats who were surveyed similarly four years ago). After Christie’s departure on Wednesday, the Trump campaign put out a memo saying that Trump led Haley 56%-40% in a hypothetical two-way race in Iowa—that actually did not strike us as that bad for Haley (or great for Trump) in a state where Haley has not appeared to be all that strong and Trump has seemed formidable. There has been very little fresh polling in Iowa, so if something interesting actually is going on there, it might not be apparent until the actual election. It also may be that nothing interesting or unforeseeable is going on, and Trump will dominate. But that’s why they play the game—or hold the election.

For more on the Iowa caucus, listen to our latest Politics is Everything podcast with Karen Kedrowski, Director of the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics at Iowa State University, and see this UVA Today Q&A with Crystal Ball Managing Editor Kyle Kondik.