Dear Readers: Join us tomorrow as UVA Center for Politics Director Larry J. Sabato interviews Time national political correspondent Molly Ball about her new book, Pelosi, an intimate, fresh perspective on the most powerful woman in American political history. The conversation will take place from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. eastern time on Friday, May 8 and will be livestreamed at: https://livestream.com/tavco/mollyball — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Many state governors have received high marks for their handling of coronavirus.

— Three of them on the ballot this November get a boost in our gubernatorial ratings this week.

— As of now, the open seat in Montana seems to be the seat likeliest to change hands on the relatively sparse presidential-year gubernatorial map.

Table 1: Gubernatorial rating changes

Map 1: Crystal Ball gubernatorial ratings

As noted in a previous edition of the Crystal Ball, even at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, it was clear that, politically, the biggest beneficiaries seemed to be governors. With few exceptions, governors across the board have seen their approval ratings rise, often by double-digits.

It remains unclear whether these ratings will stay elevated. Additionally, most gubernatorial elections are held in the midterm year as opposed to the presidential — so there’s still plenty of time for new developments to change people’s perceptions of their governors.

That said, it is difficult to imagine a new state political issue, beyond coronavirus, that puts governors on the spot in such a way. One possibility is that the immediate response to the coronavirus, which has united many voters behind their governors, gives way to thornier, more divisive arguments about how to handle the process of reopening states and dealing with the economic fallout. That may provide challengers to now-popular incumbents with an avenue of attack that they don’t possess now.

Only 11 states will hold gubernatorial elections this fall. From what we’ve seen so far, it makes sense that, given the elevated standing of chief executives across the county, we’d reconsider some ratings. This week, we have three rating changes, each in favor of an incumbent.

Historically, incumbent governors are hard to defeat, particularly those with decent approval ratings. A positive response to the coronavirus may very well bolster some of the incumbents up for reelection this time.

Cooped up in North Carolina: Fracturing Republicans and cursed seats

At the start of the cycle, one of the few genuinely competitive gubernatorial races looked like the contest in North Carolina, which is also the only one of the nation’s 10 most populous states that holds a gubernatorial race concurrent with the presidential election.

For much of his term, Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) kept generally positive approval ratings. Still, given his state’s consistently red hue in federal races and Cooper’s narrow 2016 victory — he won by 10,000 votes that year out of over 4.7 million cast — he is a logical GOP target. Republicans nominated a solid challenger, Lt. Gov. Dan Forest (R), in the March 3 primary. Like Cooper, Forest was initially elected to his current office in a razor-close vote, in 2012, but was reelected by a more commanding 52%-45% in 2016 while Gov. Pat McCrory (R) was narrowly losing to Cooper (and while Donald Trump and Republican Sen. Richard Burr were winning statewide).

In late March, Cooper announced a statewide stay at home order in response to the public health crisis. Over a month later, more than three in four voters give him positive marks for his handling of the pandemic, according to a recent Meredith College poll. A High Point University poll released Wednesday pegged his overall approval rating at 60%.

Republicans have not necessarily been united in responding to Cooper. Forest criticized Cooper’s stay at home order and has seemed to minimize the severity of the pandemic. By contrast, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) offered support for Cooper’s measures. Tillis is locked in a competitive reelection battle — his contest, along with Maine, is one of just two races that the Crystal Ball currently rates as Toss-ups.

From a purely political vantage point, it’s easy to see why Tillis might want to break from others in his party: a sampling of recent polling gives Cooper leads ranging from nine to 27 percentage points over Forest. In the end, Cooper will be hard-pressed to win a margin even on the low end of that range in such a competitive state, but he’s clearly on the right side of public sentiment and, crucially, is hitting 50% or higher of the vote in all recent polling (although just 50% on the nose in some of them).

Cooper should once again perform better than his party’s presidential and Senate candidates, just like he did four years ago. With the state’s presidential and Senate contests both looking like Toss-ups (with perhaps even a slight advantage for Democrats at the moment), Cooper appears better-positioned than four years ago.

The coronavirus pandemic is an event unprecedented in modern history and is changing the messaging and perception of candidates across the country. In a Tar Heel context, it’s given Cooper an unexpected boost, but in some regards, the trajectory of the gubernatorial race still lines up well with examples from recent decades.

Until Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC) was reelected, in 2010, political junkies scoffed that he held a “cursed” seat. Before Burr won a second term that year, the last incumbent to win a reelection bid in that seat was Sen. Sam Ervin (D-NC), back in 1968. In the three decades between Ervin’s 1975 retirement and Burr’s initial 2004 election, a string of six senators held the seat. By comparison, for much of that stretch, North Carolina’s other Senate seat was held by the late Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC) — though Helms, a conservative icon with a knack for generating controversy, would always attract spirited Democratic competition. (If Tillis loses later this year, it would be the third straight time that Helms’ former seat flipped parties — so we’ll have to see whether the Senate curse in North Carolina has switched seats.)

In any event, while Burr busted any “curse” that was associated with his Senate seat (he’s been reelected twice now), another Tar Heel office with an ominous electoral history is that of the lieutenant governor — the position now held by Forest.

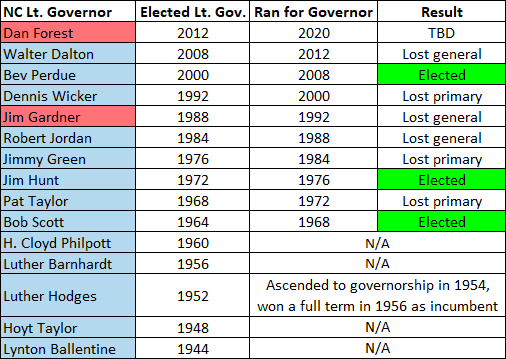

Since the tail end of World War II, 15 lieutenant governors have served North Carolina. Of those, 10 — including Forest — have sought the governorship while serving as lieutenant governor. As Table 2 shows, lieutenant governors in North Carolina have a poor record when seeking a promotion. Starting with Democrat Bob Scott, in the 1960s, every sitting lieutenant governor has tried to move up — but for each that was elected governor, two were defeated:

Table 2: Postwar NC lieutenant governors

In 2008, then-Lt. Gov. Bev Perdue’s (D-NC) victory was historic not just because she was the first woman elected governor, but also because she was the first sitting lieutenant governor elected to the state’s top job in 32 years. North Carolina limited its governors and lieutenant governors to a single consecutive term until 1977, which accounts for the shorter terms of earlier incumbents.

Drilling down further, in that same time frame, Forest is only the second lieutenant governor to challenge a sitting governor. In 1988, Gov. Jim Martin (R-NC) received a general election challenge from his Democratic lieutenant governor, Robert Jordan, but ended up winning 56%-44%.

The open seat contest to succeed Martin, in 1992, actually saw a similar dynamic, though with the partisan roles reversed: It pitted former Gov. Jim Hunt (D-NC) against then-Lt. Gov. James Gardner (R-NC). Though Hunt received positive reviews for his work on education during his time as governor and had universal name recognition, his last impression with voters wasn’t especially positive — after serving two terms as governor, he challenged Sen. Helms in a 1984 race which turned notoriously bitter. Gardner, a favorite of conservatives, had battled the more moderate elements of the nascent state Republican Party during his career. The result was another loss for lieutenant governors: even while George H. W. Bush held the state in his national loss, North Carolinians crossed over for Hunt, sending him back to Raleigh in a 53%-43% vote.

Looking forward to the fall, North Carolina is a state known for competitive elections. Aside from this year’s Senate contest, it elects 10 statewide offices collectively known as the Council of State. In 2016, five of those 10 contests were essentially coin flips — the gubernatorial result, which saw a recount, was the most salient example. Still, the Crystal Ball has rated Cooper as a modest favorite for reelection and, considering the preponderance of polls with him leading and the potential for voters to reward him for his coronavirus response, we feel confident in upgrading his prospects even while we still believe the race should be competitive (and very expensive). We’re moving North Carolina’s gubernatorial race from Leans Democratic to Likely Democratic.

GOP governors likely to retain New England foothold

Moving up the Eastern Seaboard, both New England governors up for reelection this November are looking formidable. Vermont and New Hampshire are the only states in the country that hold gubernatorial elections biennially. Govs. Phil Scott (R-VT) and Chris Sununu (R-NH) have different styles but have thrived in varying electoral environments. They were both initially elected in the turbulent 2016 cycle. They then each weathered the blue wave of 2018 well, giving strong encore performances.

In Vermont, Scott is one of the most moderate Republicans holding federal or statewide office today. Scott’s criticisms of the president — he was the first GOP governor to support an impeachment inquiry into Trump — coupled with some liberal policy stances have helped insulate him from the partisanship of his deep blue state.

Like Cooper, Scott has a challenge from his lieutenant governor; however this race has a uniquely Vermont angle. In a state where third parties run well, his main opposition is from David Zuckerman, who holds office as a Progressive. Zuckerman is a protégé of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) — as with Sanders at the national level, despite his current label, he’ll be a candidate in the Aug. 11 Democratic gubernatorial primary.

In January, with Zuckerman’s entrance into the race, the Crystal Ball downgraded Scott’s chances, moving the race from Likely Republican to Leans Republican. As a sitting statewide official, Zuckerman seemed poised to give Scott a more serious challenge than either of his two past opponents. Still, the only polling of this race — from back in February — gave Scott a 52%-29% lead while the governor’s approval stood at a healthy 57%. Notably, this was from before the coronavirus pandemic came to a head. Scott’s efforts to contain the virus seem to have been well-received, so if anything, we’re inclined to believe his standing has gone up since. Zuckerman has also argued against government-mandated vaccinations, which may be an even more fraught and fringe position these days given the public health crisis (and that has drawn criticism from another contender for the Democratic nomination, former state education secretary Rebecca Holcombe).

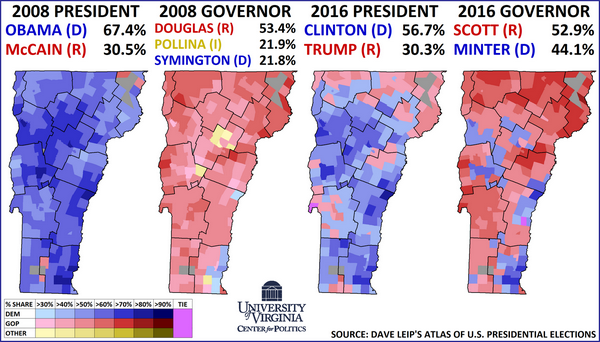

Nationally, 2016 was a stark contrast from 2008, but in Vermont, little seemed to change. One of the most historically Republican states, Vermont — along with Maine — was one of just two states that Franklin Roosevelt never carried. The most obvious vestige of the Green Mountain State’s rock-ribbed GOP history is its soft spot for moderate Republican governors. In both 2008 and 2016, the Republican presidential nominees took just 30% of the vote but their candidates for governor each got 53% (Map 2).

Map 2: Vermont presidential and gubernatorial results, 2008-2016

Though Gov. Jim Douglas (R-VT) was an entrenched figure running against divided opposition in 2008, Scott’s victory in 2016 showed that local Republicans still have a path to a majority in Vermont — even in polarized presidential years.

In New Hampshire, Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH) finds himself in an unprecedented situation — and for a reason other than the coronavirus pandemic that he’s handling.

In 2017, he entered office with a friendly legislature, as both chambers of the New Hampshire General Court (the legislature) were in the Republican hands. After both chambers flipped blue in the 2018 elections, Sununu became the first Republican governor in modern Granite State history to serve with a Democratic legislature.

As they assess the response to the pandemic, New Hampshire’s voters seem to be making a clear distinction between Sununu and Trump. Polling from Saint Anselm College in late April found that 86% of Granite Staters approved of their governor’s handling of the crisis while 13% didn’t. Meanwhile, Trump’s numbers on this question were an upside-down 42%-58%.

Also helping Sununu is that New Hampshire Democrats have a competitive primary. Much of the party establishment has lined up behind state Senate Majority Leader Dan Feltes (D) while Executive Councilor Andru Volinsky (D) is running with the support of Sen. Sanders, from next door. Feltes seems like the likeliest nominee at this point. New Hampshire has one of the latest primaries on the calendar, slated for Sept. 8 (not to be confused with the Granite State’s first in the nation presidential primary).

Like North Carolina, New Hampshire is an inherently competitive state, and Sununu’s honeymoon with the voters could end before November — the same could happen to Cooper. But, again, we think both of these incumbents — along with Scott — are better-positioned now than they were before the crisis thanks to the goodwill they have engendered in response to it.

The rest of the map

With this week’s rating changes, we now only have one contest rated in the most competitive rating categories (Toss-up or Leans one way or the other): That race is Montana, which we continue to see as a Toss-up.

Democrats are trying to win the governorship for the fifth straight time: Gov. Steve Bullock (D-MT) is term-limited after winning two close elections in 2012 and 2016, and he was preceded by former two-term Gov. Brian Schweitzer (D-MT).

However, only one of those four Democratic victories was a blowout (Schweitzer’s 2008 reelection), and four of the last five Montana gubernatorial races have been decided by less than five points.

Bullock is running for Senate against Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) in a race we call Leans Republican, even though it arguably could be a Toss-up (we examined that race in detail last week).

There are competitive primaries on both sides featuring some of state’s leading officials. On the Republican side, Rep. Greg Gianforte (MT-AL) faces state Attorney General Tim Fox and state Sen. Albert Olszewski.

On the Democratic side, Lt. Gov. Mike Cooney faces businesswoman Whitney Williams. Williams is the daughter of former Rep. Pat Williams (D, MT-AL); Hillary Clinton endorsed her earlier this week. Whitney Williams is not related to Kathleen Williams (D), who is running for the state’s at-large U.S. House seat again this cycle after running a credible challenge against Gianforte last cycle. Meanwhile, Cooney is backed by some top Montana Democrats, like Bullock and Sen. Jon Tester.

Our sense is that Cooney vs. Gianforte is the likeliest general election matchup, but these are competitive primaries. The GOP is well past due to win the Montana governorship, and Donald Trump will almost certainly carry the state again by double digits (although he may be hard-pressed to replicate the 20-point margin he enjoyed in 2016). If forced to choose, we’d probably pick the Republicans to take over this governorship. But we’re holding at Toss-up for now.

Beyond New Hampshire, Democrats are hoping to play offense in Missouri, where Gov. Mike Parson (R-MO) is running for a full term after taking over in 2018 from the scandal-plagued Eric Greitens (R). Democrats are excited about their candidate, state Auditor Nicole Galloway (D), and believe that Parson has not handled the public health crisis as well as many other state governors. But there’s not much indication Parson is truly vulnerable at this point. Democrats also hope to contest West Virginia, which like Missouri is much more Republican now than it was a decade or two ago. The Democrats have not lost a West Virginia gubernatorial race this century despite the state becoming one of the most Republican states in the nation at the presidential level. However, their 2016 victor, wealthy businessman Jim Justice, switched to the GOP in 2017.

Running as a Republican for a second term, Justice is trying to fend off former state commerce secretary Woody Thrasher (R) in what has become a nasty primary. The likeliest Democratic nominee is Ben Salango, a Kanawha County (Charleston) commissioner backed by Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who flirted with running for his old job before opting to stay in the Senate. Despite personal baggage including tax issues that are well-known to both Republicans and Democrats — after all, both sides now have experience either running against him or preparing to — Justice still looks fine, as best as we can tell, in the primary and general elections.

We rate both Missouri and West Virginia Likely Republican in our ratings.

The current lineup of state governors is 26 Republicans and 24 Democrats. Given that Montana, an open Democratic-held governorship, is the likeliest state to switch parties, Democrats probably would be relieved to get out of 2020 holding as many governorships as they do now. Republicans, meanwhile, want to flip Montana and give Cooper a run for his money in North Carolina. Given how competitive that state is, the Republicans still very well could, but we see a clear edge for Cooper right now.

Map 3: Current party control of governorships