KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Like every post-World War II president, Donald Trump witnessed a fall-off in his party’s numbers of U.S. Senate, U.S. House, gubernatorial, and state legislative seats during his presidency. That said, compared to recent presidents, the erosion on Trump’s watch was more modest than it was for his immediate predecessors.

— One obvious difference is that Trump had only one term in office and escaped a “six-year-itch” election. The only other postwar president to escape the down-ballot curse relatively unscathed was George H.W. Bush, who was the most recent president before Trump to be ousted after one term.

— Another factor may be today’s heightened partisan polarization, which makes states and districts less “swingy” than they have been in the past.

Trump’s down-ballot impact

For a defeated president, Donald Trump still seems to wield a great deal of power within the Republican Party. GOP candidates are still angling for his backing, and his decision whether to run for another term looms over the emerging 2024 Republican presidential field.

It may or may not be wise going forward, from a strictly electoral standpoint, for Trump to remain as central to the GOP as he is. On the one hand, Republicans lost control of the House and the Senate during his presidency. On the other, the down-ballot Republican losses under Trump were relatively modest compared to other recent presidents, although there are some important caveats.

With Trump out of the White House, we can close the book on how large down-ballot losses for the Republican Party were on his watch.

Trump, like his post-World War II presidential predecessors, saw his party’s control of down-ballot offices shrink during his presidency. (The two-term, same-party combinations of John F. Kennedy-Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon-Gerald Ford saw a similar pattern.)

“The surest price the winning party will pay is defeat of hundreds of their most promising candidates and officeholders for Senate, House, governorships, and state legislative posts,” this newsletter’s editor, Larry J. Sabato, wrote in 2014. “Every eight-year presidency has emptied the benches for the triumphant party, and recently it has gotten even worse.”

Why do presidents suffer down-ballot losses so consistently? The biggest factor is likely the public’s fatigue with the president’s party and the policy decisions it has made. With only a small number of exceptions, voters have regularly punished the president’s party in midterm elections, seemingly registering their displeasure with the status quo.

As I speculated in Governing in 2014, “Presidents try to accomplish things, but not everyone likes what they do. Even if they have support from the majority of voters, it’s always easier for critics — even if they’re in the minority — to block major initiatives than it is for supporters to pass them. Once a president’s agenda has been blocked, their supporters grow disappointed, joining critics in their unhappiness. The president’s overall approval ratings sag, and voters take out their anger on whichever party that controls the White House.”

Exacerbating this is the tendency for presidents to accumulate popularity-sapping scandals the longer they stay in office, from Nixon’s Watergate to Ronald Reagan’s Iran-Contra to Bill Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky. Not only do such scandals sour voters on the president’s party, but presidents who are fighting for their own political standing don’t have a lot of political capital to share with those from their party who serve at lower levels.

By becoming the first postwar president to face impeachment in his first term, Trump reached this stage at hyper speed: Even prior to the 2020 election, after just three years in office, Trump oversaw significant down-ballot losses in most categories.

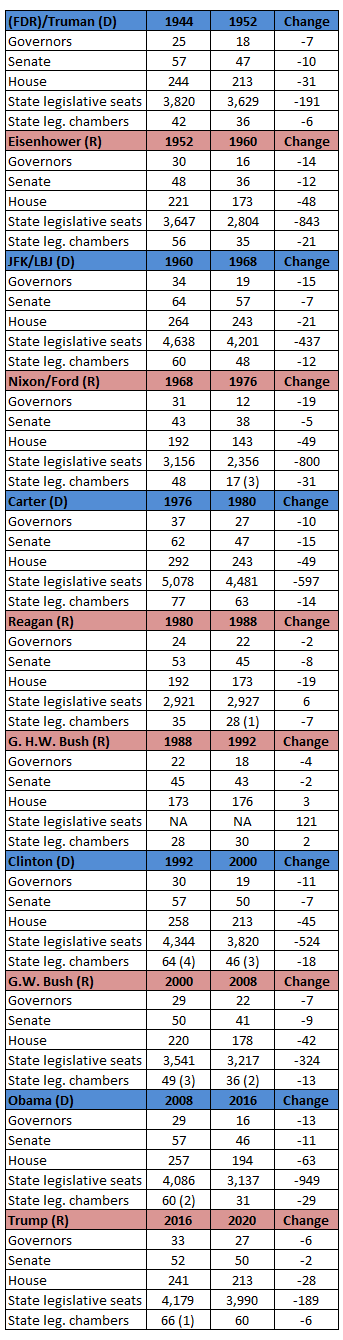

For this analysis, following one that Sabato’s Crystal Ball has updated periodically, we’ll look at five metrics: governorships, U.S. Senate seats, U.S. House seats, state legislative seats, and state legislative chambers controlled.

Here’s a look at the numbers.

Table 1: Down-ballot partisan change for postwar presidents’ parties

Notes: A number in () in the state legislative chambers controlled column indicates that one or more of the chambers was tied. The post-2020 election number for U.S. House seats assumes that currently vacant seats will be held by the incumbent party in upcoming special elections. Two legislative chambers in these calculations have had cross-party coalition control; we’ve classified the post-2016 New York Senate as Republican and the post-2020 Alaska House as Democratic. Nebraska’s unicameral legislature is officially nonpartisan, so we aren’t counting it in either party’s column.

Sources: U.S. Senate; U.S. House; CQ Press Guide to U.S. Elections, vol. ii, sixth ed.; NCSL; The Book of States, vols. 9-34; Polidata; Party Affiliation in the State Legislatures; Crystal Ball research

The Republican down-ballot performance in the 2020 election was much more robust than the party’s showing in the 2018 midterms, which helped Trump limit his overall down-ballot losses somewhat by the end of his first term.

Still, in each of the five categories we’re tracking, Trump oversaw net losses. In fact, when we last looked at these numbers in January 2020, he could at least claim a one-seat gain in the U.S. Senate. But after the twin Democratic victories in 2020 Senate contests in Georgia, that positive number turned negative.

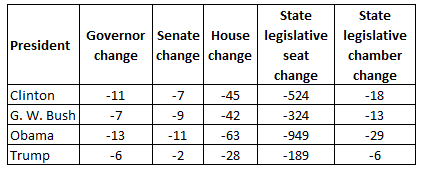

Trump’s down-ballot losses have mirrored those of his most recent predecessors. Here’s a comparison of Trump’s down-ballot losses to those under Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. None of these four presidents was able to escape a decline in any of the categories:

Table 2: Down-ballot change under most recent presidents

Why were Trump’s losses relatively modest? One possible reason is that losses under the recent Democrats (Clinton and especially Obama) have tended to be larger than those under Republicans (George W. Bush and Trump).

One explanation could be that the Democrats experienced a wholesale loss of seats in an entire region — the South — that is unlikely to swing back any time soon. The state legislative changes have been especially stark: In 1994, prior to Clinton’s first midterm, Democrats controlled 20 of the 22 state legislative chambers of the 11 states classically defined as being in the South because of their membership in the Confederacy during the Civil War. Now, Republicans hold an equally-lopsided 20-2 edge in the region’s state legislative chambers (Democrats control only the two chambers in Virginia.)

Another explanation could be that voters in midterm elections tend to be older, whiter, and more conservative, which has historically given Republicans some protection from midterm headwinds. (That said, with affluent, white, suburban Republicans becoming less enamored of the Trump-era GOP, this pattern may not hold in the future.)

Some quirks of the 2020 election also played a role. Joe Biden was favored in most polls going into Election Day, and some observers have suggested that a small but crucial sliver of moderate anti-Trump voters may have pulled the lever for both Biden and for a Republican candidate for Congress, hoping to keep Biden’s presidency in ideological check.

If true, this could help explain why the Democrats fell short in several states in 2020 where they had hoped to flip control of one or more legislative chamber, and where handicappers suggested they had a good shot at doing so.

Perhaps the most plausible explanation for the relatively modest decline under Trump — beyond the obvious one that his term lasted only four years rather than eight — is that politics today is more polarized by partisanship than it was in even the recent past. Today, few states vote differently for president and Senate; few House districts do, either. Ticket-splitting on any level is rare.

Such strong partisan alignment up and down the ballot has meant that both parties have relatively little low hanging fruit to poach from the other party. And this means that seats in each of the categories we’re tracking tend to be less swingy than they once were.

What does this historical pattern mean for Biden going forward?

On the one hand, Democrats are heading into a 2022 midterm election season in which their exceedingly narrow House majority is in jeopardy, not just from the midterm presidential curse but from reapportionment and redistricting, which could by itself produce enough district-by-district changes to flip control to the GOP.

That said, it’s possible that 2022 could break from the past pattern. The two recent examples of a president’s party gaining House seats in a midterm followed unusual occurrences — the GOP-led impeachment of Clinton before the 1998 midterms and the 9/11 attacks before the 2002 midterms — and the easing of the coronavirus pandemic and an economic recovery could theoretically boost Biden in a similar way in 2022.

In addition, the increased tendency for districts and states to sort by party could lessen the potential downside risk for Biden in 2022. Just seven Democrats currently represent districts won by Trump, which is far less than the 49 Democratic seats in 2010 that were won by Republican nominee John McCain in 2008. That fall, the Democrats lost 64 seats.

While midterm elections are usually a referendum on the party controlling the White House, there’s no modern precedent for an ousted president continuing to lead his party (especially one with a favorable rating significantly lower than that of the incumbent president). This could make the 2022 elections more of a “choice” election, which would be a more favorable playing field for the Democrats.

So even though Trump is no longer in office, his shadow may be meaningful for 2022 as well, and if Republicans have a poor showing, it may be that he would bear some responsibility. On the flip side, if Republicans do well, Trump may bear some responsibility for that, too.

| Louis Jacobson is a Senior Columnist for Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He is also the senior correspondent at the fact-checking website PolitiFact and is senior author of the Almanac of American Politics 2022. He was senior author of the Almanac’s 2016, 2018, and 2020 editions and a contributing writer for the 2000 and 2004 editions. |