| Dear Readers: We’re pleased to feature 3 items today from our Spring 2022 Crystal Ball interns: Sarah Pharr, Aviaé Gibson, and Alex Kellum. They write, respectively, on trends in youth voter turnout; the voter disenfranchisement of convicted felons; and the roots of the civility crisis in Congress.

We thank them for their help this semester in working on the Crystal Ball. — The Editors |

Youth voter turnout and the 2022 midterm

With control of both the House of Representatives and the Senate on the line in the upcoming midterm elections, the energy and turnout of young voters could have a decisive impact on the outcome of several key congressional races this election season.

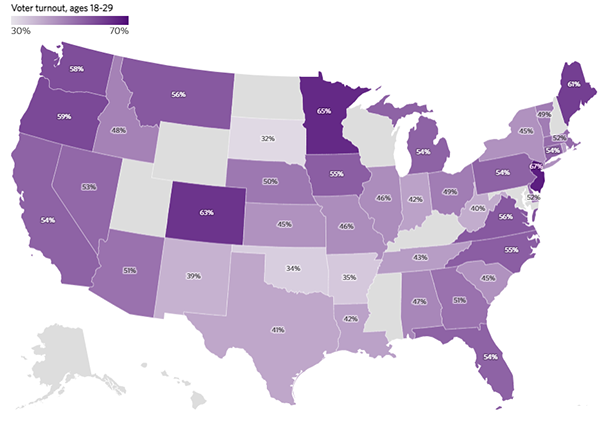

Democrats owe a good deal of their success in the 2018 congressional and 2020 presidential elections to the jump in voter turnout, especially among young voters. In the 2020 presidential election, about half of eligible voters younger than 30 cast ballots, constituting an 11-point increase from their 39% turnout rate in 2016, according to the Tufts University Tisch College Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). Younger voters are generally more Democratic than older voters. Map 1, reprinted from CIRCLE, shows its analysis of young (18-29) voter turnout in 2020 by state.

Map 1: 2020 youth voter turnout by state

Source: Tufts University Tisch College Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE)

It is worth noting that Democrats are already at a historical disadvantage; typically, midterm elections draw lower voter turnout and there tends to be a drop in the midterm congressional vote for the president’s party. Given this pattern and President Biden’s declining approval rating, public opinion could shift voters away from the Democrats in favor of the Republicans in the upcoming elections.

As major components of President Biden’s agenda remain hung up in Congress and confidence in the government’s handling of problems like inflation remains low, his approval rating continues to decline among many demographic and political groups. Specifically, the president’s approval took the largest hit with the young voter demographic: Roughly 40% of Americans ages 18 to 29 said they approved of Biden’s performance in Gallup’s aggregated polling in late 2021 and early 2022 compared to 60% in early 2021, a decline of about 20 points. That was a steeper drop than it was for the overall adult population, which was 14 points.

Young Democratic voters may be less likely to turn out for a midterm election in support of a president they are not enthusiastic about. Pew Research Center’s 2021 political typology survey indicates that the youngest groups in the Republican and Democratic coalitions tend to feel the least connected to, or satisfied with, both parties and are historically among the least politically active.

Another warning sign that youth interest in voting in the 2022 midterm election may decline is the increase in negative attitudes about political engagement and efficacy of voting since 2018. According to the Spring 2022 Harvard Youth Poll, the percentage of youth agreeing that “political involvement rarely has any tangible results” has risen from 22% in 2018 to 36% in 2022, and the percentage of youth who believe that their vote doesn’t “make a real difference” increased from 31% in 2018 to 42% in 2022. However, the poll also reported that, as of now, the youngest voters “are on track to match 2018’s record-breaking youth turnout,” but it is possible that the mix of young voters who show up will be more Republican-leaning than in 2018, which one might expect in what could be a Republican-leaning year.

Let’s look at how changes in the voting patterns of young people could impact 2 key senate seats Democrats are trying to defend in 2022: those of Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) and Raphael Warnock (D-GA).

Young voters in Nevada preferred President Biden over former President Trump by 33 points in 2020, which was one of the highest margins among young voters in competitive states and which demonstrates their electoral importance in a very competitive state. In the last midterm, the youth share of the electorate doubled in Nevada, from about 6% in 2014 to 12% in 2018.

Nevada will be automatically mailing ballots to all registered voters in 2022, “an election practice that was associated with higher youth voter turnout in 2020,” per CIRCLE.

Recent elections have shown that Democratic gains in Georgia can be strongly affected by youth turnout. A higher-than-average turnout by young voters contributed to Biden’s narrow win in 2020 and were a part of both Senate runoff victories in early 2021, which provided Democrats control of the chamber.

Georgia also had a slightly higher share of young people in its electorate (20%) than the national average (17%) in the 2020 election, per the national and state exit polls.

The electoral impact of young voters in 2022 should not be underestimated; if the Biden administration, congressional Democrats, organizers, and other stakeholders don’t invest in engaging young voters prior to the midterm elections, they could risk alienating an already pessimistic demographic ahead of Toss-up elections in states like Georgia and Nevada this year.

— Sarah Pharr

The current state of felon disenfranchisement

Presently, there are only 2 states, in addition to the District of Columbia, where convicted felons have access to the ballot while serving their sentence. Roughly three-quarters of the states have various methods for felons to recover their right to vote, ranging from automatic restoration after release to reapplication post-prison, parole, and probation, while the remainder have more stringent requirements for convicted felons to restore their voting rights (and some are denied restoration altogether). The National Conference of State Legislatures has more information about how the states handle felon voting rights. This raises the question of how felon disenfranchisement may impact (or have impacted) election outcomes.

For the first time since the 1970s, the felon disenfranchised population has decreased in recent years. In 2016, there were about 6.1 million people disenfranchised by a felony conviction. With states reconsidering their state policies and the passage of reform, this number fell to 5.2 million people in 2020, according to the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that focuses on criminal justice issues.

Black Americans are likelier than other groups to experience felon disenfranchisement. As of 2020, 1 in 16 Black Americans, otherwise eligible to vote, are disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, or about 6% of the adult Black population. With a disenfranchisement rate 3.7 times higher than other groups, parallels can be drawn from the post-Civil War era that may help explain the pervasive rate at which Black Americans are stripped of their right to vote.

After the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the end of the Civil War in 1865, newly freed men and women were faced with the difficult reality of navigating a new socioeconomic status coupled with growing questions about their rights and citizenship status. The additions of the 14th and 15th Amendments sought to address these concerns by solidifying their citizenship status and right to the ballot. However, with the implementation of these new frameworks, individual states seemingly retaliated by passing disenfranchisement laws specific to those with felony convictions.

Between the end of the Civil War and 1880, at least 13 states, over a third of the nation at the time, implemented broad felony disenfranchisement laws, according to a 2017 report from the Brennan Center for Justice. With the growing usage of Black Codes, especially in southern states, enacting broad felony disenfranchisement provided an efficient avenue to obstruct formerly enslaved Black people from civic engagement. Prior to 1865, select states did pass laws to disenfranchise convicted felons; however, this only applied to specific charges rather than a broad application. The change from specific charges to broad disqualification links back to the origins of mass incarceration.

In recent years, there have been multiple states that have recently reformed their policies surrounding felon disenfranchisement. In 2020, there were 7 states where 1 in every 7 Black Americans was disenfranchised, approximately twice the rate of Black Americans living elsewhere. One of these states is Virginia; however, in recent years, the state has made efforts to expand the right to vote. In 2021, former Gov. Ralph Northam (D-VA signed an executive order allowing over 69,000 convicted felons to have their rights restored, regardless of completion of probation or parole. However, during this year’s General Assembly session, the Virginia Senate, slimly controlled by a Democratic majority, attempted to pass a constitutional amendment ballot issue where Virginians would have the opportunity to vote for the automatic voter restoration of ex-felons. However, this proposal was halted in the Republican-controlled House of Delegates. Washington state and New York have also made recent changes that allow convicted felons to get the right to vote back automatically following the completion of their sentences.

What are the political consequences of disenfranchisement? A 2019 study sought to uncover whether felon re-enfranchisement would have an effect on the outcome of U.S House of Representatives elections from 1998 to 2012. For the purposes of their study, the researchers conducted their study under the assumption that all ex-felons regardless of individual state law would be allowed to vote. While the researchers found that no House majority would have been flipped during this time, there is some evidence pointing to re-enfranchisement potentially increasing the number of Democratic seats during this timeframe, gaining anywhere from a potential 0-3 additional seats.

Although the re-enfranchisement of felons would not have resulted in a turnover of the House majority party in recent years, that does not necessarily mean it is not an important issue for elections. Voting remains one of the cornerstones of the democratic process and civic participation. As the authors of the research study also argued, voting may serve as a “potentially valuable” aspect of ex-felons’ rehabilitation and reintegration into society. In addition, re-enfranchisement may also help to address the disparity of the voices of racial minorities in the democratic process. While some may say that barring felons and ex-felons from voting is a safe avenue to avoid politicians who could be soft on crime, the public, as well as current legislators, need to be aware of the inherent racial disparities that disproportionately affect people of color.

— Aviaé Gibson

The civility crisis in Congress

(Author’s note: The following is an exercise in idealism. Civility in politics only works if it is adopted by both sides. While that does not always happen, we can at least lay out how politics should work, even if that is not always the case.)

On the night of March 1, 2022, President Biden gave his State of the Union address to assembled members of Congress. As the president talked about helping American veterans suffering from injuries and illnesses, controversial Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert (R, CO-3) shouted from the floor, “you put them there — 13 of them,” likely referring to American service members who were killed during the U.S. evacuation from Afghanistan last year. To hear a member of Congress heckle the president at that moment was no surprise: Congress is suffering from a civility crisis.

In the past, when a person was elected to Congress, they would often move their entire family to Washington D.C. Members lived next door to each other, their children went to the same schools, they played golf and went to dinner with each other’s families. Today’s members spend significantly less time in D.C., leaving their families in their home states and living in rented apartments, or for some, even sleeping in their office. To idealize the earlier culture of Congress may be hindsight bias, as it was anything but a completely harmonious and civil institution before its members were in Washington less regularly, but when what little time they spend in Washington is taken up by work alone, it is easy to see why members of Congress no longer develop civil relationships with each other.

The cost of housing in D.C. makes it challenging for members of Congress who are not independently wealthy to stay in the city for long periods of time, as well as the ease of travel that the modern era affords means that members can easily travel back-and-forth from Washington when necessary. However, this alone is not the cause of the current crisis: Another culprit is the change in how party politics is conducted.

When the Democrats lost what seemed at one time like a “permanent majority” in Congress in the latter half of the 20th century — Republicans flipped the Senate in 1980 after a generation of Democratic majorities and made inroads in the House — politics became less about compromise and more about being as different as possible from the opposing party. In her book, Insecure Majorities, Frances Lee describes how a competitive, two-party Congress changed the nature of politics. “The primary way that parties make an electoral case for themselves vis-a-vis their opposition is by magnifying their differences,” which explains the more extreme ideological shifts in Congress. Unfortunately, this change bleeds over to relationships among members, as “nonideological appeals accusing the other party of corruption, failure, or incompetence are at least equally valuable and can potentially attract swing voters, as well as fire up the base.” This means that members of Congress have no incentive to form relationships with those across the aisle — it is better to stay hostile and maintain the image of your party as the opposite of the other.

While responsibility for this development lies with Republicans, Democrats, and the nature of party politics, many point to Republican Newt Gingrich as the champion of confrontational, no-compromise politics. During Gingrich’s time in Congress, he oversaw the rise of a new wave of confrontational, conservative members who were encouraged to play dirty, refuse compromise, and wage war against the Democrats. As Lee highlights in her book, Gingrich “wanted Republicans to withdraw from bipartisan negotiations,” and used his Conservative Opportunity Society to strategize with other Republicans on how to confront and attack Democrats at every turn. Compromise was not an option, so there was no real reason for congress people to make an effort to maintain good relations with members of the other party.

Of course, while Gingrich is the standout figure of this style of politics, the Democratic Party is not necessarily an innocent victim of Republican polarization. Robert Byrd, the longest-serving Democratic senator and the party’s leader at the time, played a major role in restructuring the Democrats following the loss of the Democratic majority in 1980. Byrd steered the party towards a more combative style of politics, and away from the bipartisan compromise that often characterized the Senate earlier in its history. For example, Byrd began whipping votes against a debt ceiling increase sought by the Reagan Administration, to the dismay of many Democrats, Lee writes. Gingrich may get the spotlight for his inflammatory rhetoric and role in reshaping the Republican party, but the developments of modern politics led leaders of both parties to push back against the idea of compromise and mutual respect. Both Democrats and Republicans now encouraged their members to stay true to the party line, and politics became about attacking the other party as much as it was promoting one’s own. Which leaves us in the situation we face today — a polarized congress where members do not even get along with each other outside of politics.

While there are more policy-oriented possibilities, such as lowering rent in D.C. or requiring members to stay in a dormitory when Congress is in session, the fundamental change that needs to happen is much simpler. Members should remember that regardless of party, they are here for the same goals — to ensure life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for the country. Nobody should expect politicians to agree on everything, but they could at least expect them to get along outside of the chambers.

Politicians are a model for how Americans view people from other parties; when average Americans see their members of Congress heckling during the State of the Union, and know that they do not interact outside of their sessions, they will treat the other party as an enemy, further polarizing the masses.

Would more civility result in better policy? Probably not, as the nature of politics has changed, and a more competitive Congress means that compromise will continue to become more difficult. But it is not impossible to picture a competitive Congress where members disagree ideologically, but at least treat each other with respect. Ideally, better informal relationships between members of Congress will inspire better relationships between average Americans with differing partisanship.

— Alex Kellum