KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Senate races are increasingly converging with presidential partisanship, to the point where the huge overperformances that were so common a decade or two ago have become much less common.

— Since 2000, the number of senators who have run more than 10 points ahead of their party’s presidential nominee has decreased sharply.

— This trend helps explain why we currently rate Democratic-held West Virginia as Leans Republican and started off Montana and Ohio as Toss-ups.

Senate race trends since 2000

Last week, when we put out our first look at the 2024 Senate map, we issued a rare rating: We started an incumbent off as an underdog. Specifically, we put the West Virginia contest in the Leans Republican category. Though Sen. Joe Manchin has not officially announced his plans, the reality is that any Democrat, even as one as successful as Manchin, faces a daunting challenge in West Virginia.

Some of Manchin’s worries are state-specific. One of the (several) unexpected success stories for national Democrats last year was their showing in state legislative races: They gained governmental trifectas in several states and held their own in the overall state legislative seat count across the nation. But the Democratic floor continued to sink in West Virginia. In the state legislature, Republicans now hold an astonishing 88 seats in the 100-member state House and 31 of 34 state Senate seats. When Manchin first entered office as governor, after the 2004 elections, Republicans only held about a third of the seats in the legislature.

But, as we have discussed in previous articles, there has been a larger trend driving recent elections for Senate: realignment along presidential lines. Between the 2016 and 2020 Senate elections, only one state, Maine, voted for presidential and Senate candidates of opposite parties. Though this trend would obviously imperil Manchin, Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Jon Tester (D-MT), if they seek reelection, also will run in states that Donald Trump or the eventual GOP nominee will likely carry, although neither states has become as ruby red as West Virginia (Brown says he will run again, Tester has not yet announced).

But, if Manchin were to run again — and win — how much of an exception to the recent trend would he be? Assuming West Virginia votes for the GOP nominee by roughly 40 points, as it did in 2016 and 2020, a Manchin win would surely be predicated on a high level of crossover support.

We’ve gone back through the 6 most recent presidential elections examining that question. The short answer is that in the Senate of the early 2000s, 40-point or more overperformances actually occurred with some regularity. Even in 2012, Manchin himself posted such a showing. But since 2016, no major party senatorial nominee has run more than 25 points ahead of their party’s presidential nominee.

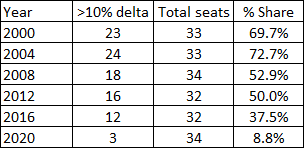

So a 40-point overperformance would be a massive outlier in today’s electoral environment. But even loosening our criteria somewhat, even a 10-point overperformance — in the ballpark of what Brown or Tester likely will need to win — would be something of a rarity. Table 1 goes back to 2000 and tracks how many senators performed at least 10 points better than their party’s presidential nominee.

Table 1: Double-digit overperformances in Senate races since 2000

Note: Compares the 2-party vote for Senate to the 2-party vote for president. Table excludes the following Senate races: Arizona 2000, Idaho 2004, Arkansas 2008, Maine 2012, Alaska and California 2016, and Arkansas 2020.

Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U. S. Presidential Elections.

In both 2000 and 2004, about 70% of Senate races featured a difference of 10 or more percentage points in margin compared to the top of the ticket. But by the Obama era, that number hovered around 50%. As straight-party a year as 2016 was, Table 1 shows that 2020 was actually more so in some ways: Though no states actually produced a split-ticket outcome, more than a third of the Senate races featured a double-digit difference with the presidential race. But by 2020, just 3 Senate races did — meaning that more than 90% of the total Senate races had a 2-party margin within 10 points of their respective state’s presidential race.

With that, we’ll look at each presidential cycle since 2000 and identify the top overperformers.

2000

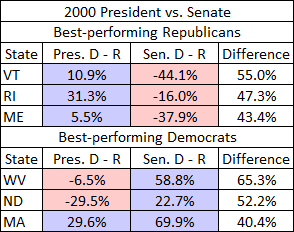

2000 saw 6 incumbent senators, 3 from each party, run 30 points or more ahead of their presidential nominee.

By the late 1990s, New England had emerged as a Democratic-leaning region in presidential politics. Between the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections, most New England states swung to then-President Bill Clinton by double-digits. Many of Clinton’s gains stuck in 2000, as his then-Vice President, Al Gore, carried 5 of the region’s 6 states — Gore only barely missed out on New Hampshire, making him the most recent Democratic nominee to lose a New England state. But in the 2000 Senate elections, the region’s traditional affinity for moderate Republicans was still evident down the ballot. In Vermont, Republican Jim Jeffords won a final term by running 55% ahead of then-candidate George Bush’s showing in the Green Mountain State. Citing the GOP’s increasingly conservative direction, Jeffords became a Democratic-caucusing independent less than a year into his new term — Jeffords’s switch gave Democrats control of the Senate for much of the 107th Congress. In nearby states, Rhode Island’s Lincoln Chafee and Maine’s Olympia Snowe outran Bush by 47 and 43 points, respectively.

The top 3 overperformers on the Democratic side were all long-tenured incumbents with popular local brands. Though Bush’s 52%-46% victory in West Virginia came as a surprise on Election Night, Mountain State voters remained overwhelmingly loyal to Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd — a fiddler who was first elected in 1958, he was known for steering resources to his state and was something of a folk hero. Byrd took nearly 80% of the vote. Manchin currently holds Byrd’s seat. In North Dakota, a small state that lends itself well to retail politicking, Sen. Kent Conrad (D) first won a Senate seat in 1986 and won comfortably in the pro-GOP 1994 cycle (he had effectively switched seats in 1992). Republicans seemed to feel Conrad was too entrenched to defeat. Finally, Massachusetts’s Ted Kennedy, with his seniority and golden surname, easily dispatched a scandal-plagued Republican.

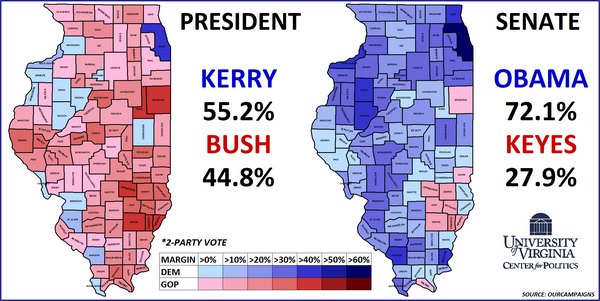

2004

As the 21st century got underway, voters’ ticket-splitting habits began to wane. In 2004, Bush, then an incumbent, ran well in the South and his coattails helped Republicans flip 5 open Senate seats there. Bush’s 60%-38% showing in South Dakota also helped topple then-Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle (D) in a squeaker. But, in 2004, there were still over half a dozen senators who ran 30 points or more ahead of their party’s presidential nominees.

In Arizona, the late Sen. John McCain (R) was at the peak of his popularity. After running against Bush for the GOP presidential nomination in 2000, the two Republicans had buried the hatchet. McCain’s credentials as a “maverick” on some issues, most notably campaign finance, likely helped his crossover appeal. He took over three-quarters of the vote against weak opposition. In Iowa, Sen. Chuck Grassley’s (R) annual 99-county trips around the state had made him a political institution in the state. And going back to New England, Sen. Judd Gregg (R) benefitted from token opposition — after a scandal sidelined Democrats’ preferred nominee, they were left running a 94-year-old liberal activist.

For 2004, a North Dakota Democrat again makes the list of top overperformers. Sen. Byron Dorgan had represented North Dakota in Congress since the 1980 election: as the farm crisis hurt Republicans electorally in the region that decade, Dorgan was always reelected with massive margins. He made the jump to the Senate in 1992. Hawaii’s Dan Inouye was in much the same category as Byrd in 2000: Though Bush performed well for a Republican in the state, the senator’s seniority paid electoral dividends. In Indiana, Sen. Evan Bayh, one of the chamber’s key moderate Democrats, comfortably won a second term.

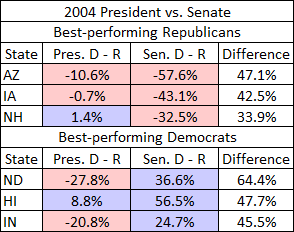

One other notable overperformer in 2004 was not an incumbent — Barack Obama easily won his first and only term in the Senate in Illinois against carpetbagging conservative activist Alan Keyes, who had replaced a previous, scandal-plagued nominee. In fact, Obama turned in the largest overperformance of any non-incumbent during the 2000 to 2020 timespan (Map 1).

Map 1: Illinois in 2004

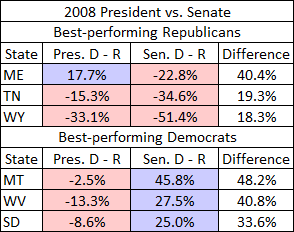

2008

In 2008, Democrats had an undeniably strong cycle — they were aided by then-candidate Obama’s voter mobilization efforts and a pervading anti-George W. Bush sentiment.

Though Democrats tried to tie Maine Republican Sen. Susan Collins to the outgoing president, New England ticket-splitting was again on display. Democratic Rep. Tom Allen, who represented the Portland-based 1st District, made the Iraq War a central issue of the campaign. But Collins had cultivated an image as a parochial, bipartisan senator. On the campaign trail, she could point to high ratings from usually liberal-leaning groups: in 2007, she had a perfect score with the League of Conservation Voters, for example. Collins won a third term with over 60% as Obama carried Maine comfortably. In Tennessee and Wyoming, Sens. Lamar Alexander and Mike Enzi were veteran officeholders in overwhelmingly red states. Their races attracted little attention. Alexander had a habit of winning Shelby County, which includes Memphis — over his career, he had been the GOP nominee in 6 statewide races and carried it each time. In 2008, as Obama carried Shelby County by close to 30 points, Alexander carried it 51%-47%..

The biggest overperformer in 2008 was Montana’s Max Baucus. Though the Democrat was a key player in the Senate — by 2008, he chaired the Finance Committee — his margin was padded by weak GOP opposition. His Republican opponent, Bob Kelleher, was a perennial candidate who had run under multiple partisan affiliations in the past — his institutional support was nonexistent. Like Byrd, Jay Rockefeller, West Virginia’s other senator, had a long career in state politics. A Democrat from a famously Republican family, he came to the Senate in 1984 immediately after serving 8 years as governor. As the state’s leader during a tough economic times, Rockefeller had to work hard to win that 1984 contest, but he quickly became entrenched. In the early 2000s, Republicans did not have much of a bench in West Virginia, and Rockefeller got the same underfunded challenger he ran against 6 years earlier. Sen. Tim Johnson represented South Dakota for 5 terms in the House before making the jump to the Senate. In 2006, Johnson suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and spent the better part of a year recovering. Constituents seemed to rally around their senator, and in 2007, when he returned to work, he was greeted with a standing ovation in the Senate chamber. Though Baucus, Rockefeller, and Johnson all scored impressive margins, it may be worth noting that Obama’s showing in each of their states was respectable, too.

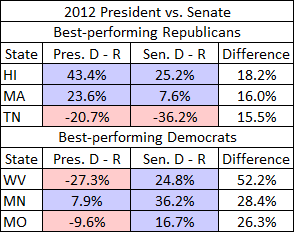

2012

In 2012, with Obama successfully running for reelection, some of the biggest overperformers in the Senate were actually losers. In Hawaii, Republicans ran their strongest candidate, former Gov. Linda Lingle. The Senate contest turned into a rematch of sorts: Rep. Mazie Hirono (D, HI-2) emerged from the Democratic primary — she had lost the 2002 gubernatorial race to Lingle 52%-47%. But the difference in the outcome was a prime illustration of the differences between state-level and federal races. Obama carried his native state by over 40 points for a second time, helping Hirono to a 25-point win. In Massachusetts, Sen. Scott Brown won a come-from-behind special election victory in 2010 to replace the late Ted Kennedy — his Democratic opponent ran a lazy campaign and Brown’s image as pickup truck-driving everyman fit the moment. In 2012, Brown was initially ahead in polls and cast himself as an independent Republican. But Democrats consolidated behind law professor Elizabeth Warren, who fundraised well. Warren pulled ahead by the end of the campaign to beat Brown 54%-46%. Tennessee Sen. Bob Corker would have won easily in most circumstances anyway, but he faced a controversial Democrat who the Washington Post mused could have been “2012’s worst candidate.” (we may add that there was ample competition for that title)

The biggest overperformer, from either side, in 2012 was actually Joe Manchin. In 2010, he was initially expected to waltz into Byrd’s old seat in a special election but got something of a scare from businessman John Raese, who pulled ahead in some polls. But Manchin took advantage of Raese’s gaffes and won by a larger-than-expected 10 points. Raese filed for a rematch against Manchin, but after his 2010 loss, he attracted little outside help. Though voters did not have much of an appetite for a Raese candidacy, West Virginia continued its rightward lurch at the presidential level: Mitt Romney became the first Republican presidential nominee in history to sweep all the state’s counties — something Donald Trump replicated in 2016 and 2020, but the state’s totally-red map came as at least a slight surprise at the time. Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who made a strong debut in 2006, kept strong approval ratings and did not draw a top-tier opponent. She carried all but 2 counties in her state, and as a presidential candidate in 2020, had good reason to stress her “electability.” Finally, Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill seemed to have a tough race for a second term in her red-trending state. In September, a poll from SurveyUSA showed her trailing the newly-minted GOP nominee, Todd Akin, by a 51%-40% margin. But shortly afterwards, Akin made his infamous “legitimate rape” comment when he was asked about abortion — Akin’s comment was roundly denounced and he became something of a pariah.

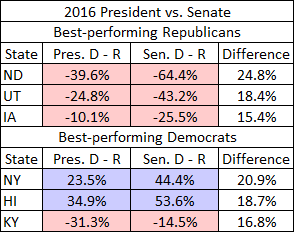

2016

When political analysts discuss the types of gains that Donald Trump made in 2016 over Mitt Romney’s 2012 showing, much of the attention, rightfully, goes to several marginal states bordering the Great Lakes. But the state that swung hardest to Trump that year was actually just west of that region: North Dakota. Indeed, things were so tough for North Dakota Democrats in 2016 that, in some of the races for lower statewide offices, Libertarians performed better than Democrats. After being elected three times as governor, Republican John Hoeven won Dorgan’s open Senate seat in 2010. From 2000 to 2010, Hoeven expanded his margin all four times he was on the ballot: he continued that pattern in 2016. The presidential race in Utah was an odd situation: Trump, with his in-your-face attitude and less than pious personal record, was not a natural fit for Utah’s Mormon community. As Trump carried the state with 45% in a 3-way race, Sen. Mike Lee performed more like a “normal” Republican in the state. Going back to the Great Plains, though Democrats initially tried to mount a serious effort against Grassley, his local brand remained popular — although his still-strong 60%-36% margin was closer than his past reelection races.

In New York, Sen. Chuck Schumer (D), who was known for his media savvy and the special attention he gave to the Upstate region, was a chronic overperformer. He was reelected with over 70% of the vote for the second time in his career. In Hawaii, Hillary Clinton’s margin was several points lower than Barack Obama’s but Sen. Brian Schatz (D), who replaced Inouye, continued the trend of incumbent overperformance there. Sen. Rand Paul, a libertarian-ish Republican, always seemed like an unorthodox fit for his demographically-Trumpian state. As Trump carried the state by 30 points, Paul’s opponent, Lexington Mayor Jim Gray, ran over 50 points better than Clinton in parts of the traditionally Democratic east (although Paul still won overall by about 15 points).

As an aside, 3 of 2016’s top overperformers — Hoeven, Grassley, and Schumer — were up last year, and all posted less impressive performances. In fact, each took just about 56% of the vote. Schumer’s role as Democratic leader likely would have hurt his crossover appeal anyway, and his weak margin was part of an underwhelming showing for New York Democrats overall. Grassley, who was reelected at age 89, may have paid an “age penalty” and got a decently-funded Democratic challenger. Hoeven’s margin was hurt by the independent candidacy of Rick Becker, a state legislator who ran to his right. Becker took close to 20% of the vote. But even if all of Becker’s votes were transferred to Hoeven, Hoeven’s margin would have still been slightly down from 2016. So these examples show that some senators are electoral juggernauts until they aren’t.

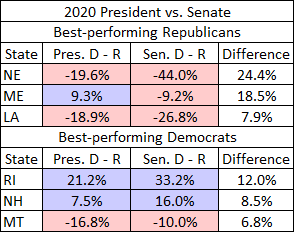

2020

The most recent cycle saw the Senate outcomes closely linked to presidential results. In Maine, Collins made a return appearance on the list of top overperformers, although she was in a much more competitive race. As is apparent in the table, the top overperformances on both sides are just a lot smaller than they were in previous cycles. By 2020, Maine had transitioned to a ranked-choice system of voting — a fact that, for the Senate race, wasn’t very relevant because Collins, impressively, won an outright majority. On paper, Collins beat her Democratic opponent, state House Speaker Sara Gideon, by a 51%-42% spread. However, it is worth pointing out that a liberal third party candidate, Lisa Savage, took 5%. She encouraged her voters to rank Gideon second — in Savage’s absence, it is easy to see Gideon doing a few points better. In Nebraska, Sen. Ben Sasse (R) kept strong approval ratings in his own right, but faced a scandal-plagued Democrat who received no party backing. Louisiana, with its jungle primary, reelected Sen. Bill Cassidy (R) outright — he took 59% but had several opponents from both parties. Republican candidates in the jungle primary outvoted Democratic candidates by 27 points, or about 8 points better than Trump’s 2-party margin in the state.

On the Democratic side, veteran Sen. Jack Reed, who has represented Rhode Island in the Senate since the 1996 elections and currently chairs the Armed Services Committee, ran furthest ahead of Biden. Still, there were signs presidential realignment was catching up to Reed: his margin was down 8 points from his 2014 spread, and 2020 was his first reelection result where he failed to carry all the state’s towns. Staying in New England, as Biden was expected to carry New Hampshire, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen led her Trump-endorsed opponent, Corky Messner, in every poll of the race. Republicans made a serious effort to unseat Shaheen in 2014, but by 2020, she did not have a top-tier race. Finally, Democratic Gov. Steve Bullock, who was reelected in 2016 even as Republicans won all other statewide offices in Montana, challenged first-term Sen. Steve Daines. Bullock ran 7 points ahead of Biden, but had the same issue as Linda Lingle: he was a governor seeking a Senate seat in a state that leaned the other way in federal races.

Conclusion

One commonality among many of these overperformances is that there were established incumbent senators facing weak, underfunded opponents. While the eventual strength of the challengers to Manchin, Brown, and Tester remains to be seen, Republicans surely will be focused on defeating all 3 of them and will be working to recruit the strongest possible candidates and provide substantial outside spending support.

If Manchin and Tester run for reelection, something that may help them is that small-state senators tend to be more likely to overperform. Of the 36 Senate elections we featured in the tables from 2000 to 2020, 27 of them were in states with fewer than 10 electoral votes.

Beyond that, the trend in the relationship between presidential and Senate results in recent elections is clear: The differences between the 2 races on the ballot are generally getting smaller, and even in just the last couple of decades, there has been a huge decline in the amount of ticket-splitting we see in these races. That does not automatically mean Manchin, Tester, and Brown are going to lose, but the challenge each faces is clear.

— Crystal Ball interns Victoria Mollmann and Evelyn Duross assisted in the research for this article.