KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— As five sitting members of the House have already lost primaries — and some states have yet to vote — 2020 could see the most primary losers in a non-redistricting cycle since 1980.

— The circumstances of some of this year’s primary losers are in some ways similar to past troubles that have undone incumbents in primaries.

— Both parties have seen members lose primaries this cycle, but the Republicans’ electoral prospects have, on the whole, been more adversely affected.

— There are a handful of other House incumbents who may be vulnerable as the primary season picks up again next week.

Another 1980 parallel

Back in April, we discussed some similarities between the 1980 election and this one. Down the ballot, there may be another connection between this year and the election four decades ago: An unusually high number of House incumbents may lose primaries, at least for a non-redistricting year.

Usually, at the congressional level, turnover is highest in election years following redistricting, or in other words, years that end in “2” (1992, 2002, 2012, etc.). Between changes in apportionment — states losing or gaining seats — and partisan considerations, members of the same party can be thrown into common districts, which naturally increases the number of members who end up losing in primaries.

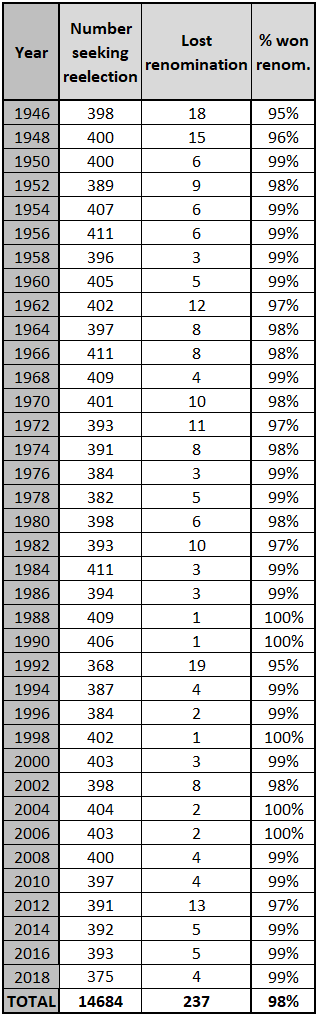

Table 1 illustrates this dynamic. Note that the number of incumbent losses is often higher in redistricting years. Typically just a few House incumbents lose primaries in any given year.

Table 1: House incumbents in primaries, 1946-2018

Sources: Vital Statistics on Congress, Crystal Ball research

Five incumbents have lost primaries out of the 278 races featuring incumbents that have been held so far this primary season. As the primary season resumes next week, another 117 House incumbents will seek renomination.

When incumbents do lose primaries, there is usually a good reason why. Redistricting can be a key driver, as we see in years that end in 2 or when districts are altered in other years.

Scandal can also be a factor. In 1980, the Abscam scandal helped end several careers in Washington, and it contributed to Florida Republican Richard Kelly’s primary loss (an unrelated scandal contributed to another one of the primary losses, that of California Democrat Charles Wilson).

So is ideology: One of the 1980 losers was an Alabama Republican, John Buchanan, who primary voters deemed not conservative enough after Buchanan, elected thanks in large part to Barry Goldwater’s 1964 Southern strength, became markedly less conservative in the decade and a half following his initial victory.

A perception that a long-time incumbent has lost touch with the district — another problem that can hurt incumbents — bedeviled Bob Duncan, an Oregon Democrat who ended up being defeated handily by Ron Wyden, who remains in Congress four decades later (albeit in the Senate).

One other loser, Florida Democrat Ed Stack, won a 1978 primary victory against a damaged incumbent but then couldn’t defend his seat two years later.

The sixth 1980 incumbent primary loser was an accidental congressman, Democrat Bennett Stewart of Chicago. Democratic machine leaders placed him on the ballot late in the 1978 cycle after the incumbent died. The following cycle, he was trounced by Harold Washington, a future Democratic mayor and opponent of the old-school Chicago Democratic machine.

If just one more member fails to clinch renomination, 2020 would tie 1980 as the most recent non-redistricting election year where more than five members lost primaries. With that in mind, let’s consider how each of the losses of this cycle played out. Some of the problems that hurt incumbents four decades ago are reminiscent of some incumbent issues this year.

Primary losers of the 2020 cycle

While some of the primary losers this cycle suffered from self-inflicted gaffes, or just got lazy, the first primary loser was a rather open-and-shut case: in Chicagoland, Rep. Dan Lipinski (D, IL-3) was simply not in alignment with the increasingly liberal tendencies of his party’s electorate.

Lipinski, a moderate Blue Dog, first won his seat in a way that could be described as a case study in Chicago machine politics. In the 2004 cycle, his father, then-Rep. Bill Lipinski, who had held the seat since the Reagan era, ran unopposed in the March primary, but withdrew from the ballot in August. A close ally of the state’s powerful House Speaker, Mike Madigan, Lipinski had his son put on the ballot as the party’s replacement nominee. In a way, this is reminiscent of Stewart’s ascension to Congress in 1978: Lipinski was able to become the Democratic nominee without actually having to win a primary.

But unlike Stewart, Lipinski established a foothold in the district. Upon arriving in Congress, the younger Lipinski maintained that his voting record would be much like his father’s — in other words, voting close to the party line on fiscal matters, but with tradition in mind when it came to social issues. The 3rd District, which encompasses Chicago’s southwestern neighborhoods, had historically been working-class territory that was shaped by waves of white ethnic groups that immigrated there beginning in the mid-19th century — such as Poles, Irish, and Italians, though the area has a growing Hispanic population. A cultural unifier among these groups was Catholicism, so the Lipinski formula seemed to fit the area well.

An ardent opponent of abortion, Lipinski voted against the Affordable Care Act in 2010, reasoning that its provision banning federal funding for abortion was insufficient. Though his abortion stance, and his perceived closeness to the Chicago machine, attracted some primary challengers throughout the years, he met his most serious primary opponent in 2018. Marie Newman, a political consultant, charged that Lipinski was too conservative for the district — it supported Hillary Clinton 55%-40% in 2016 — and she was endorsed by a laundry list of progressive groups.

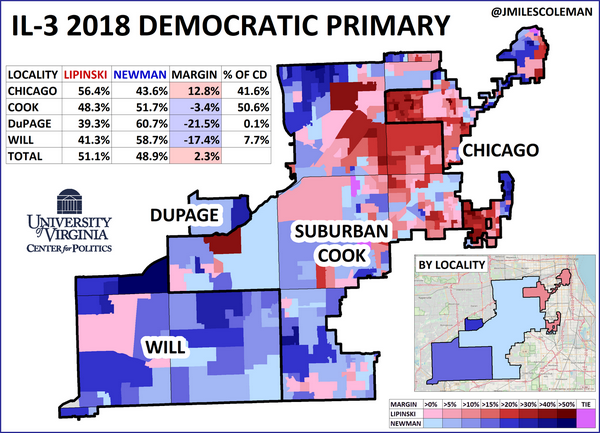

Lipinski won that 2018 primary, but by just a 51%-49% margin, and with a telling geographic divide. Lipinski carried the more working-class Chicago-proper part of the district by 13 points but lost the western, suburban parts of the district — areas that tend to have higher rates of educational attainment, and are likely more transient (Map 1).

Map 1: 2018 IL-3 Democratic primary

Lipinski had some advantages in 2018 that were absent, to some degree or another, in 2020. With its March primary, Illinois is one of the first states on the calendar to vote — the abbreviated timeframe likely helped the incumbent, who had high name recognition. For her part, Newman had essentially been running for a rematch since her 2018 loss, which gave her more time to introduce herself to voters.

Structurally, Lipinski benefited from the state’s open primary system. In fact, a key part of his campaign’s strategy was convincing Republicans to vote for him in the Democratic primary. In 2018, Lipinski’s strategy was successful. There was no contested Republican congressional primary in IL-3, and, as a conservative Democrat, he drew GOP partisans over into his primary. In 2020, Republicans had a three-way primary of their own, giving their voters less reason to participate in the other primary. Compounding that was Illinois being among the first states to vote after the COVID-19 pandemic became a national emergency — as most of its voters cast ballots in person on Election Day (as opposed to other states that relied more on mail-in voting), turnout was down across the board. With that turnout dynamic, it’s easy to see how the Democratic primary would have been driven by the loyal partisans.

Newman won the primary 47%-45%. The general breakdown was similar to 2018, but Newman cut Lipinski’s margin in Chicago in half.

A few months before the primary, Lipinski’s political instincts looked questionable, as he signed an amicus brief, along with over 200 Republican members of Congress, that urged the Supreme Court to reconsider its Roe v. Wade decision. Lipinski’s opposition to abortion was already known in the district, but it seemed to highlight the issue that he was most out of sync with the Democratic electorate on, and at the worst possible time. In South Texas, Rep. Henry Cuellar (D, TX-28) has a similarly pro-life record but didn’t sign the letter — he also faced a well-funded progressive challenger in a March primary, but held on, albeit narrowly.

It wasn’t until June that another incumbent congressman lost a primary — though for political observers of all stripes, this member’s defeat seemed overdue.

In northwestern Iowa, Rep. Steve King (R, IA-4) has had a penchant for controversial, if not outright racist, comments since his initial election, in 2002. Over his 18-year career, he had the luxury of representing the most Republican-leaning seat in Iowa, which helped insulate him from general election challenges. In 2012, Democrats were excited about their chances to beat King, as they recruited Christie Vilsack, the wife of Tom Vilsack, a popular former governor who served in the Obama administration. In the end, Vilsack didn’t attract much crossover support — King was reelected 53%-45%, matching Mitt Romney’s showing in the district.

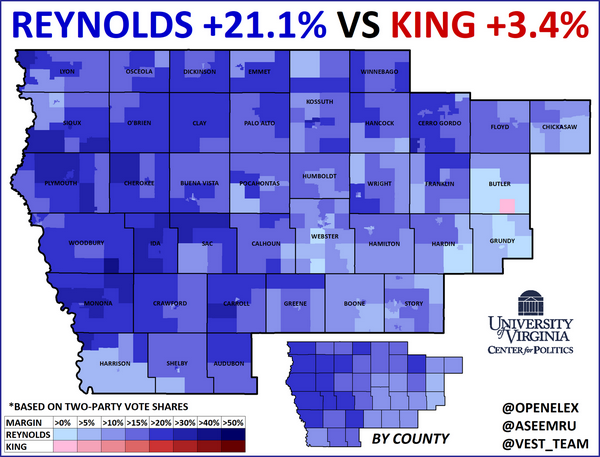

In the Trump era, King seemed to dial up the intensity of his remarks, to the point of wading into white nationalism. He received token opposition in the 2018 primary but faced another well-funded Democratic opponent in first-time candidate J. D. Scholten, who ended up outraising him by better than 3:1. Though King ended up winning, it became clear that his personal baggage was jeopardizing the GOP’s hold on the seat — while Gov. Kim Reynolds’ (R-IA) election hinged on her nearly 61% share of the (two-party) vote in the 4th District, King’s margin was just over 3%. King outperformed Reynolds in just one of the district’s roughly 500 precincts, and ran more than 20% behind her in many counties (Map 2).

Map 2: Steve King’s 2018 underperformance in IA-4

King did not suffer from a legal scandal — which differentiates him from some of the losing House incumbents in 1980 — but his comments essentially rose to the level of scandal, and made him significantly more vulnerable than he otherwise would have been. After his close call, King made no efforts to moderate. Instead, shortly after his reelection, in an interview with the New York Times, he pondered, “white nationalist, white supremacist, Western civilization — how did that language become offensive?” As a result, House Republican leadership stripped King of his committee assignments, essentially relegating him to outcast status within the caucus. This helped King’s 2020 primary challenger, state Sen. Randy Feenstra — who announced his campaign shortly after 2018 — argue that, racism aside, King was simply an ineffective congressman.

Leading up to the early June primary, King trailed badly in fundraising, an ominous sign for his prospects. Feenstra, who represents a deeply-red, ethnically Dutch senate district in the state’s northwestern corner, won the primary 46%-36%. Much of Feenstra’s margin came from his senate seat, which gave him nearly three-quarters of the vote.

With King out of the picture, the Crystal Ball immediately upgraded the GOP’s chances in IA-4, moving it from Likely Republican to Safe Republican. Scholten is running again, and has over $1 million cash on hand, but Feenstra has a motivated base in northwestern Iowa, and Trump will probably carry the seat by a significant margin again (he won it 60%-33% in 2016).

If King’s exit helped Republicans secure a red district, a result less than two weeks later, in the Crystal Ball’s home district, has loosened their hold on another.

As we detailed in mid-June, Rep. Denver Riggleman (R, VA-5) lost a strange, drive-through convention to Bob Good, a local official in Campbell County. Riggleman, a libertarian-leaning Republican, drew the ire of some conservative activists by officiating a gay wedding in 2019 and otherwise not being sufficiently conservative for some, though he did earn the president’s endorsement. Good, by contrast, ran as a “Biblical conservative,” and, at a low-turnout convention, prevailed 58%-42%.

Party conventions have long been a quirk of Virginia politics; local parties can choose to hold them, as opposed to traditional primaries. Given their smaller electorate, results are more often determined by hardcore partisan activists — this can produce candidates who are seen as less electable in general election settings.

Since our look at the VA-5 last month, Democrats overwhelmingly nominated Dr. Cameron Webb, who may have a timely profile as a Black physician. Bob Good’s fundraising was objectively poor heading into the convention and, as of the end of the June, he still badly trails Webb. Though this is a red-leaning district — even Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) fell 2% short there in his landslide reelection, and it’s very likely to stick with Trump — national Republicans may need to put more effort into it than they should ordinarily have to. Had Riggleman’s fate been decided in a primary, it’s likely he’d have been renominated.

Though the votes have been slow to come in, 16-term Rep. Eliot Engel (D, NY-16) conceded to his primary challenger, school principal Jamaal Bowman. Immediately after Election Day, Bowman had a 61%-35% lead — the result has narrowed as more votes have been counted, but he should still win convincingly.

Engel, who chairs the House Foreign Affairs Committee, seemed like an incumbent whose campaign chops had just gotten rusty — another familiar problem with incumbents who lose primaries. As this is a heavily blue district, taking in parts of Westchester County and the Bronx, he rarely had serious opponents.

In the heat of a competitive race, Engel questioned the need for his colleagues to get involved in primaries — a curious charge, considering he came to Congress himself in 1988 by ousting a scandal-plagued incumbent in the Democratic primary. Another ironic twist was that in the 2000 edition of the Almanac of American Politics, an Engel staffer was quoted saying, “The congressman says he likes primaries — they keep you sharp.” He also faced questions about how often he was back home in the district, particularly during the pandemic.

There’s no question that NY-16, which Clinton carried three to one in 2016, will stay in Democratic hands.

In another New York City district, Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D, NY-12), with her base in Manhattan, had a close primary call but appears to have held on — with ballots still being tallied, she has a tenuous, though growing, lead over college professor Suraj Patel. Maloney beat Patel by a much more comfortable 59%-41% in the 2018 primary.

The most recent primary loser of the 2020 cycle appears to be an incumbent who was caught sleeping. Representing Colorado’s Western Slope since 2011, Rep. Scott Tipton (R, CO-3) lost by nine percentage points to first-time candidate Lauren Boebert. Tipton had Trump’s endorsement, but didn’t seem to be running an active campaign — for one thing, he spent nothing on advertising.

Like the situation with VA-5, the result of the primary prompted the Crystal Ball to downgrade the GOP’s prospects — we moved both races from Likely Republican to Leans Republican. As 270towin author Drew Savicki detailed this week, CO-3 has a GOP lean: in 2018, Gov. Jared Polis (D-CO) won the state by 11%, but lost the district by 4%. Democrats renominated former state Rep. Diane Mitsch Bush, who lost to Tipton by 8% in 2018. Over the past decades, voters in the area have been supportive of some Democrats, though their most recent Democratic congressman, former Rep. John Salazar, cultivated something of an independent image — in 2010, the National Rifle Association endorsed his campaign.

Looking forward

So what’s been the overall effect of primary challenges this cycle? For Democrats, both IL-3 and NY-16 are firmly in the blue column, so their new nominees represent more of change in tone than substance — even with his socially conservative stances, Lipinski supported the Democratic Party on most major votes. Republicans have essentially taken one step forward but two steps back. Though booting King was long overdue, and moves his seat off the table, they’ve gone with riskier nominees in VA-5 and CO-3. It seems that, for a party that’s already struggling to take back the House, these developments could be problematic.

On the horizon, there are still some House members who may be vulnerable in primaries, including a few who are on the ballot next Tuesday.

In Kansas, first-term Rep. Steve Watkins (R, KS-2) was recently charged with voter fraud. Though he’s complained that the charges are politically motivated, his main primary opponent, state Treasurer Jake LaTurner, was quick to raise the issue. LaTurner’s internal polling, from immediately after the Watkins charges were announced, suggested that the congressman’s standing in the district had been damaged: while LaTurner and the likely Democratic nominee, Topeka Mayor Michelle De La Isla, were about tied, Watkins trailed De La Isla by 12 percentage points.

Next door in Missouri, 10-term Rep. Lacy Clay (D, MO-1) is in a rematch with his 2018 primary opponent, activist Cori Bush. Clay won the primary by 20 points in 2018, but with primary day approaching — it’s on the same day as Kansas — he’s gone negative on Bush, which sometimes is a sign of vulnerability. Clay, just like Lipinski, succeeded his father in Congress. Clay did win his initial House primary, way back in 2000, but he has been pushed somewhat in recent primaries. Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D, AZ-1) also faces a primary challenge from the left on Tuesday, although he’d be a more surprising loser than the two others we’ve mentioned.

Two members of the “Squad,” Reps. Rashida Tlaib (D, MI-13) and Ilhan Omar (D, MN-5), also face credible primary opposition next week and the week after, respectively, although both should be OK. Rep. Richard Neal (D, MA-1), a committee chairman like Engel (Neal chairs Ways and Means), also appears to be facing credible opposition, as does Rep. Stephen Lynch (D, MA-8), one of least liberal House Democrats. The Massachusetts primary is not until Sept. 1. There are a handful of others that may merit watching, and sometimes incumbent losses can come out of the blue (there wasn’t much advance warning that Tipton was in real danger, for instance).

If even one of these members lose — or someone else not mentioned here — 2020 will match 1980’s previous high watermark for incumbent primary losses in a non-redistricting year.

— Crystal Ball interns Ella Berg, Ellie Bowen, Tommy Dannenfelser, Halinta Diallo, Tanmay Gupta, Micah Rucci, Eva Surovell, Krishan Patel, and Bennett Stillerman helped research this piece.