| Dear Readers: The University of Virginia Center for Politics has released a trailer for its latest documentary, Common Grounds.

Produced entirely by student interns at the Center for Politics, the documentary explores the political climate at UVA through the eyes of several students of differing political beliefs. A primary goal of the project was to foster an atmosphere at UVA that is conducive to constructive discourse. The documentary features interviews with students who reflect on the importance of civility — or the absence of it — in today’s political climate. In another key part of the film, students sit down in a group to discuss the political issues and aim to find consensus. As part of the project, the students painted the phrase “There is common ground on our Grounds” across the Beta Bridge. Located only a few blocks from the iconic Rotunda, the bridge is a focal point on Grounds. The full documentary will premiere later this summer. For more information on the project and the students behind it, see the recent feature from UVA Today, “‘Common Ground on Our Grounds’: Bridging Political Differences.” Virginia held its Democratic primary last night, setting up perhaps the marquee race of the 2021 calendar. Our look at the primary and the road ahead is below. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Former Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D-VA) easily captured the Democratic nomination for governor on Tuesday night, setting up a matchup with businessman Glenn Youngkin (R).

— Virginia’s Democratic trend gives McAuliffe an early edge, but it’s common for Virginia gubernatorial races to look a lot different than the previous year’s presidential race.

— Matchups for the state’s down-ballot races were also set, but don’t expect a ton of ticket-splitting among the state’s three statewide elected offices.

The early line on McAuliffe v. Youngkin

So it’ll be former Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) versus Glenn Youngkin (R) for the Virginia governorship this fall. We continue to rate the race to replace outgoing Gov. Ralph Northam (D-VA) as Leans Democratic. McAuliffe is favored, but not overwhelmingly so.

Youngkin has a path, although he’ll have to simultaneously appeal to hard-core Donald Trump voters as well as lapsed Republicans who have voted Democratic in recent years. A significant factor for the fall is one over which neither candidate has control: perceptions of President Joe Biden. If Biden’s modest honeymoon continues, and his approval rating remains over 50%, Youngkin may struggle to make the case against McAuliffe and continuing Democratic control of Richmond. But if there’s some downtick for Biden, that could threaten McAuliffe. The former governor won his first term in 2013 even amidst trouble for national Democrats — Barack Obama’s approval was underwater at the time of the election amid negative stories about the rollout of the website for Obama’s signature Affordable Care Act — but McAuliffe also only narrowly escaped against a hard-right challenger, then-state Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli (R).

In picking McAuliffe and Youngkin, Virginians of both parties selected nominees that are within the mainstream of their respective parties. That’s another way of saying neither are really moderates, but voters also passed on more ideological options in the respective party nominating contests.

Youngkin, a wealthy former co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, won his party’s nomination a month ago at what party officials called an “unassembled convention.” About 30,000 delegates cast ranked-choice ballots at about 40 locations across the commonwealth, and Youngkin outlasted several other competitors.

Virginia Democrats opted for a traditional statewide primary, which McAuliffe was always clearly favored to win over a splintered group of lesser-known challengers.

Despite what turned out to be a predictable and uncompetitive primary, Democratic turnout on Tuesday was robust, at least by Virginia standards. Votes are still being counted, but it appears that around 485,000 votes were cast in the Democratic primary, not that too far shy of the 540,000 cast four years ago. The Democratic turnout four years ago was cited by many as a sign of the white-hot Democratic voter engagement in Virginia just months after Donald Trump had won the White House. While it’s not clear to us that primary turnout is predictive of future outcomes, if you do care about primary turnout as a barometer, the Democratic showing this time was still fairly strong in our estimation, particularly because this gubernatorial primary was sleepier than the one between Northam and former Rep. Tom Perriello (D, VA-5). Northam won that race by 12 points. McAuliffe won on Tuesday with 62%, more than 40 points ahead of his nearest competitor (the scattered polls of this race did a good job conveying McAuliffe’s dominant position).

The key question is whether Virginia has become so Democratic that a Republican can’t win here anymore. We don’t think that’s the case, but Republicans haven’t won a statewide contest in a dozen years, and Biden just posted the biggest presidential win in Virginia by a Democrat in the post-World War II era.

However, gubernatorial races don’t always fit a state’s overall partisanship — even in a time when federal partisanship is increasingly influential down the ballot.

There are just two senators who hold seats in states that the other party’s presidential candidate won by double digits in 2020: Sens. Jon Tester (D-MT) and Joe Manchin (D-WV), who represent states that Donald Trump won by 16 and 39 points respectively. (As an aside, this fact likely has a lot to do with Manchin’s willingness to buck the leadership of his party on bills such as the Democrats’ election overhaul.) Meanwhile, there are six governors who lead states that the other party won by double digits for president: Govs. Charlie Baker (R-MA), Larry Hogan (R-MD), and Phil Scott (R-VT) on the Republican side, and Govs. Laura Kelly (D-KS), Andy Beshear (D-KY), and John Bel Edwards (D-LA) on the Democratic side. It’s not easy to buck the prevailing partisan trend in a statewide race these days, but it is more doable in a gubernatorial race than a Senate race.

Virginia gubernatorial races also often feature significant swings from the previous year’s presidential race. In order to win, Youngkin needs to do a little more than 10 points better statewide than Donald Trump did in 2020. A half-century’s worth of modern Virginia gubernatorial races show such an improvement is very much achievable, but there are important caveats to the history.

Modern two-party politics at the state level in Virginia dates back to 1969, when Linwood Holton (R) became the first Republican to win the state’s governorship since Reconstruction. Of the 13 modern gubernatorial races, the party that didn’t hold the White House won 10 of them. Holton is one of the exceptions, and he was followed four years later by former Gov. Mills Godwin (R), who performed the same feat that McAuliffe is attempting: winning two nonconsecutive terms as the Old Dominion’s chief executive. Godwin won his first term in 1965 as a conservative Democrat, and then won as a Republican in 1973 against then-Lt. Gov. Henry Howell, a liberal firebrand who ran as an independent Democrat (there was no formal Democratic nominee in that election). Richard Nixon was president during both Holton and Godwin’s victories. McAuliffe was the third and most recent presidential party candidate to break the Virginia governorship’s familiar White House jinx, and if he wins this fall, he’ll be the fourth.

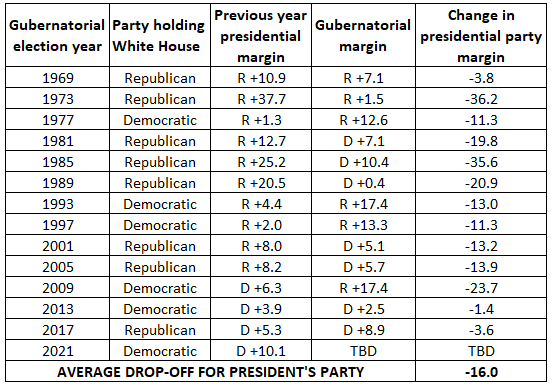

Table 1 shows Virginia’s modern gubernatorial election results. In all 13 races, the president’s party lost ground compared to how that party’s presidential nominee performed in Virginia the prior November. So it’s reasonable to think that, at the very least, Youngkin should be able to perform better than Trump did. In 10 of these 13 contests, the non-presidential party gubernatorial nominee improved upon his presidential nominee’s showing by 10 points or more — the level of improvement Youngkin needs to win. The average improvement is 16 points. If Youngkin were to match that, he would win by six points in November.

Table 1: Virginia gubernatorial results compared to previous year’s presidential, 1969-2017

Source: Our Campaigns, Virginia Department of Elections, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

That said, the average may not be very useful. For one thing, we’re only talking about 13 elections here — a tiny sample size. For another, Virginia has changed dramatically in the course of this timeframe, going from a state that voted considerably to the right of the nation in presidential elections to one that votes to its left. Also, there were more blowout presidential elections in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s than there are now, which can skew these comparisons. For instance, Richard Nixon won Virginia by an astronomical margin in 1972, 37.7 points, and then Republicans only barely won the following year’s gubernatorial race. But we don’t see those kinds of presidential blowouts any more, which means one wouldn’t expect such a sharp change the following year. And, perhaps most importantly, partisanship is more predictable now than it was several decades ago.

But the overall point still stands: Just because Biden won the state by 10 points in 2020 doesn’t mean it can’t shift enough a year later for Youngkin to win.

What would a Youngkin victory look like? For one thing, Youngkin would be the first modern Republican gubernatorial nominee, in all likelihood, to win without carrying any of the fast-growing suburban/exurban enclaves of Henrico County in Greater Richmond and Loudoun and Prince William counties in Northern Virginia. These counties have all zoomed toward Democrats in recent years, each giving Ralph Northam victories of 20 points or more in 2017 (and Biden 25 or more in 2020). Even though Ed Gillespie (R) carried Loudoun in his narrow loss against Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) in 2014, this was before Donald Trump’s takeover of the GOP hastened the realignment of highly-educated and diverse suburban counties such as these. Youngkin will need to cut Democratic margins in these counties, but winning them is unrealistic, at least in a close race. Youngkin also will need GOP-friendly turnout and giant margins in sparsely-populated but now extremely Republican western Virginia.

Localities Youngkin almost certainly will have to flip back to Republicans after Biden carried them include Chesterfield (in Greater Richmond), Stafford (between Northern Virginia’s bigger population centers and Richmond along I-95), and — perhaps most importantly — the big Republican-leaning swing cities in Hampton Roads, Chesapeake and Virginia Beach. Both voted for Trump in 2016, but flipped to Northam in 2017 and Biden in 2020. Many observers see Hampton Roads as a key not only to the statewide races but also to the battle over the state House of Delegates, where Democrats won a 55-45 majority two years ago. Because of census data delays, this year’s state House races will be contested on the same map as two years ago — which may mean another set of elections next year under the new maps and then another set of regularly-scheduled races in 2023 (the state Senate isn’t on the ballot again until 2023, so the Democrats’ 21-19 edge is safe). If Youngkin puts up a strong showing in the governor’s race, he could provide enough lift to down-ballot Republican candidates to flip the Virginia House even if he himself does not win.

Beyond the gubernatorial race, Virginia Democrats also chose their nominees for lieutenant governor and attorney general, which are the state’s other two statewide elected positions. Incumbent Attorney General Mark Herring (D) fended off a challenge from state Del. Jay Jones (D) as he seeks a third term (while Virginia governors cannot run for reelection to consecutive terms, there are no term limits for the other two statewide elected positions). State Del. Hala Ayala (D) defeated several other Democratic contenders for the lieutenant gubernatorial nod. Ayala will face former state Del. Winsome Sears (R) for the lieutenant governor post, and Herring will face state Del. Jason Miyares (R). Both Herring and Ayala are from Northern Virginia, as is McAuliffe; Miyares represents and Sears represented state House districts in Hampton Roads, while Youngkin lived in the area for a time as a teenager.

Perhaps the composition of the Republican ticket could help in that electorally-vital Tidewater region. Meanwhile, the Democrats are all from Northern Virginia, the vote-rich engine that powers Democratic statewide victories. Ultimately, we doubt there’s much significance to the geographic makeup of the tickets, but we suspect the all-NOVA composition of the Democratic ticket will get some attention.

The LG and AG races are likely to be tied to whatever happens in the gubernatorial race — or, at least, more tied to the top of the ticket now than in the past. Table 2 shows the modern election results for the three statewide offices. While there continues to be some differences among the races, in three of the last four statewide elections, there’s been a less than seven-point gap between the best Democratic and best Republican margins in these races. The differences in 2013 were mostly because of a weak Republican lieutenant gubernatorial candidate — the other two contests were quite close, especially the AG race, which Herring won by just 165 votes out of 2.2 million cast.

Table 2: Statewide results in Virginia, 1969-2017

Source: Our Campaigns, Virginia Department of Elections, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

While the margins in the three statewide races won’t be identical, they likely will track relatively closely with one another. So the best bet is a sweep for one side or the other, unless all the races are decided by slim margins. The same party has swept all three races in the last three elections.

Virginia appears likely to have the most competitive gubernatorial race of 2021. The only other regularly-scheduled contest is in New Jersey, where first-term incumbent Gov. Phil Murphy (D-NJ) will face former state Assemblyman Jack Ciattarelli (R), who won his party’s nomination on Tuesday night. New Jersey is more Democratic than Virginia, and Murphy is an incumbent who does not at this point appear to have major problems. The recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) will also take place at some point later this year, but the recall effort appears to be losing steam as opposed to gaining it.

Ultimately, Republicans would love to come out of 2021 with more governorships than they hold now (27), but it doesn’t necessarily mean trouble for them in 2022 if they don’t, given that these three races are happening in states that are more Democratic than the nation as a whole. Democrats can’t make up any ground this year, but they can try to use this year’s contests as a way to gauge how prepared they are for the challenges of the midterm.