KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— If no candidate gets to 270 Electoral College votes, the U.S. House of Representatives would pick the next president.

— The House has not had to pick a president in nearly two centuries. In the event of such a tiebreaking vote, each state’s U.S. House delegation would get to cast a single vote. The eventual president would need to win a majority of the 50 state delegations.

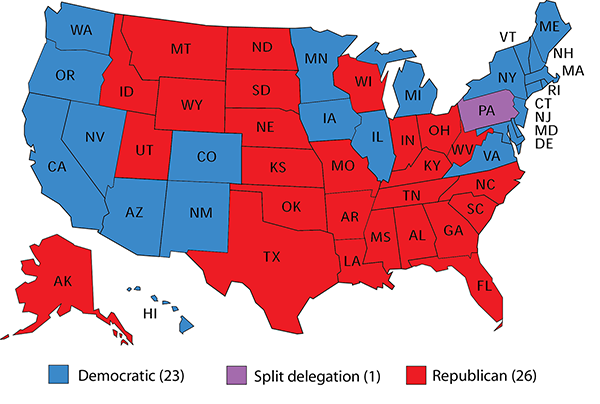

— Republicans control 26 delegations and Democrats control 23, with one tie (Pennsylvania). That is a slight improvement for Democrats from this time last year, although that improvement is based on a fluke and may not endure.

— The GOP remains favored to control a majority of House delegations following this November’s House election.

Why a 269-269 tie would likely go to the GOP

The possibility that the Electoral College could split 269-269 is remote, but possible. As my colleague J. Miles Coleman notes this week, there are scenarios under which the single electoral votes produced by Maine and Nebraska’s unique congressional district electoral vote allocation systems could tip the election one way or the other, or even produce a tie. One of these tie vote scenarios, the one Miles highlighted, is actually plausible: Switching Michigan, Pennsylvania, and NE-2 from Republican to Democratic, and otherwise holding everything else constant from the 2016 election, would produce a tied Electoral College.

We looked at the GOP edge in the event of a tie about a year ago, and we thought we’d update our outlook at the dawn of the election year. There have been some subtle changes, but the GOP’s advantage endures. To illustrate this edge, we’re doing something new: adding ratings to the 50 state delegations.

In a scenario in which no presidential candidate wins the 270 electoral votes required to be elected president, the newly-elected House of Representatives would select the president from among the top three finishers in the Electoral College. In a 269-269 scenario, that would mean the House would just select between the Democratic and Republican nominees, as they would be the only recipients of electoral votes.

Each state’s House delegation gets a single vote, meaning California (with 53 House members) and Texas (with 36) have the same power in this vote as states like Vermont and Wyoming, which have only one apiece. The District of Columbia, which has three electoral votes but no voting representation in the House, would not get to participate in the House vote — it’s the only entity with voting power in the Electoral College that does not have any voting power in the tiebreaking process for president and vice president.

The Senate’s role in the event of a tie would be to pick a vice president, and each of the 100 senators gets a vote.

A majority of state U.S. House delegations — 26 of 50 — must vote for a candidate in order for that candidate to win the presidency. If no candidate can assemble a majority, the person selected as vice president would serve as president (assuming the Senate could actually produce a majority for vice president — the hypotheticals here are starting to give us a headache).

Despite being in the House minority, Republicans retain a bare majority of delegations: They hold 26 of the 50 delegations. Democrats hold 23, and one state is split: Pennsylvania, at nine seats apiece.

This tabulation may actually understate the Republican advantage, though — or, rather, understate Democrats’ difficulty in netting the three delegations they would need in order to grab an outright majority.

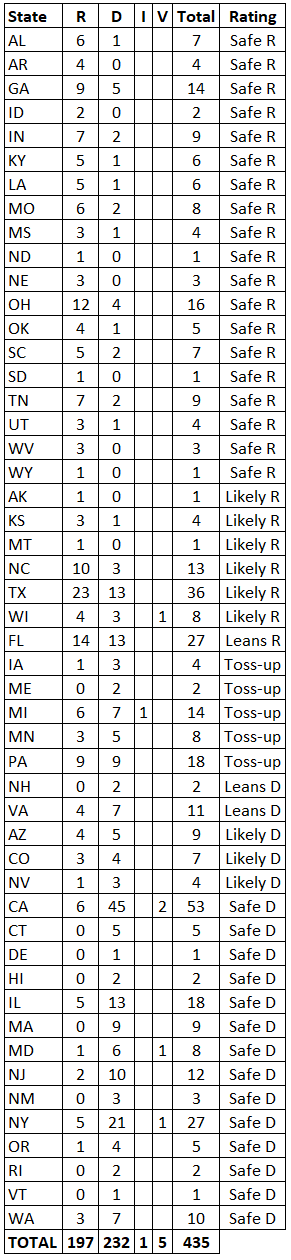

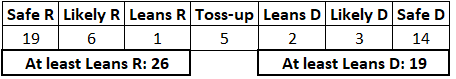

Table 1 and Map 1 show the current makeup of the state U.S. House delegations. We have assigned ratings — from Safe Republican to Safe Democratic — assessing the likelihood of either side winning control of each delegation. This basically translates our individual House ratings into state-level ratings. Table 1 sorts the state delegations from Safe Republican (top) to Safe Democratic (bottom), with the most competitive delegations in the middle. Table 2 summarizes the ratings.

Map 1 and Table 1: Current control of U.S. House delegations

Notes: R is all Republican-held seats; D is all Democratic-held seats; I is all independent seats; V is all vacant seats.

Table 2: Crystal Ball ratings of House delegation control

Based on our assessment, Republicans start with a hard floor of 19 delegations, with an additional six likely to stay Republican. That’s 25 delegations right there. Florida, where the GOP holds a 14-13 edge, is leans Republican — that’s 26, the magic number.

Meanwhile, Democrats have 14 safe delegations, three likely delegations, and two leans delegations. That’s only 19.

Of the five Toss-up delegations, four are currently held by Democrats (the fifth is tied Pennsylvania). Of these Toss-ups, the Democratic edge in Michigan’s delegation is extremely tenuous. In 2018, Michigan elected seven Democrats and seven Republicans to the House, but Rep. Justin Amash’s (I, MI-3) defection from the GOP has technically given the Democrats a 7-6-1 edge in the state. However, Amash is, in all likelihood, a substantial underdog to win reelection as an independent in what could be a three-way race in a GOP-leaning though competitive district. If he did get reelected, would he side with Democrats in a House vote? After all, he was the only non-Democrat to back impeachment. Or would he ally with Republicans and perhaps prevent Michigan from casting a vote altogether?

Beyond Michigan, Democrats also have to defend vulnerable Toss-up districts in states such as Iowa and Maine to hold their majorities in those delegations.

A couple of the Likely Republican states, Alaska and Montana, are states with a single member. Montana is an open seat, while Rep. Don Young (R, AK-AL), the dean of the House, has been in the House for almost half a century. If either race is highly competitive (one or both might be, although Republicans are clearly favored to hold both), it’s possible that the issue of how a Democratic, at-large House member might vote in a tied Electoral College scenario could come up in a campaign.

There is some precedent for this becoming a campaign issue. In 2004, Stephanie Herseth (D) — who now goes by Stephanie Herseth Sandlin after marrying Max Sandlin (D), a former House member from Texas — won a special election for the at-large House seat in South Dakota. During the subsequent general election, when George W. Bush was locked in a close reelection battle with John Kerry, Herseth’s GOP opponent pressed her on how she would cast the South Dakota House delegation’s vote for president if the presidential election went to the House. As recounted in the 2006 edition of the Almanac of American Politics, she said she would back Bush because Bush would win the state, as of course he did. (Herseth Sandlin eventually lost her seat in the 2010 GOP wave.)

The reason we bring this up is to say that the behavior of individual members might matter quite a bit in the event of a vote, and just because a party might have a numerical advantage in a state doesn’t mean that the delegation would vote that way (although the strong likelihood is that individual members would not break with their party on such an important vote). Again, we don’t want to go down a rabbit hole here and agonize over hypotheticals based on the extremely unlikely event of an Electoral College tie. Rather, we just want to note the inherent uncertainty — and potential craziness — of a process that none of us have ever seen in action in our lifetimes.

One final point: Presidential elections have a significant impact on down-ballot races, including those for House and for Senate. A presidential election that produced a 269-269 split in the Electoral College would likely be close nationally: it’s possible that the Democrat would run ahead of Hillary Clinton’s two-point national popular vote edge from 2016, but probably not that far ahead. Our best guess is that in such a closely-divided scenario, there probably wouldn’t be dramatic changes in the House — or, at least, in the overall partisan control of House delegations.

In other words, one can envision scenarios in which Democrats take a majority of House delegations, but that would probably be part of a larger national victory that would produce a clear Democratic victor for president, too, making a tiebreaking vote in the House unnecessary.

Overall, Republicans retain an edge in the tiebreaking procedure for president, and they are quite likely to maintain that advantage if such a tiebreaker becomes necessary after the November election.