| Dear Readers: Join us Thursday at 2 p.m. eastern for our latest episode of Sabato’s Crystal Ball: America Votes. We’ll be reacting to the vice presidential debate and discussing the latest in the presidential race as Election Day draws closer. If you have questions you would like us to address during the webinar about the debate, specific races, or other developments in the campaign, just email us at [email protected].

You can watch live at our YouTube channel (UVACFP), as well as at this direct YouTube link. Additionally, an audio-only podcast version of the webinar is now available at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast providers. Just search “Sabato’s Crystal Ball” to find it. Today, we’re pleased to feature guest columnists Dudley L. Poston Jr. and D. Nicole Farris, who ponder the possible political and reapportionment impacts of what has become a rallying cry for some Democrats: statehood for Washington, D.C. and/or Puerto Rico. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In the upcoming 2020 elections, if Joe Biden defeats Donald Trump, and if the Democrats win control of the Senate and maintain control of the U.S. House, statehood for the District of Columbia and for Puerto Rico is a real possibility.

— On June 26, 2020, the U.S. House voted 232-180 to establish Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital, as the 51st state.

— A referendum for P.R. statehood will be held in Puerto Rico on Nov. 3, 2020. If the referendum favors statehood, and if Puerto Rico submits a petition for statehood, and if Biden beats Trump, and if the Democrats win control of the Senate, then there is a chance that the House and Senate will pass a resolution authorizing statehood.

— Statehood will result in four new senators, two each for the District and for Puerto Rico. Three or perhaps even all four will likely be Democrats.

— Statehood will result in the District receiving one seat in the House and Puerto Rico receiving four seats. The size of the U.S. House likely would remain at 435. Therefore, five states could each receive one less House seat in the 2020 apportionment: New York, Florida, Texas, Montana, and Illinois.

Introduction

On Sept. 26, President Donald Trump selected Amy Coney Barrett as his nominee to fill the seat on the Supreme Court of the recently deceased Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader in the Senate, is scheduling a confirmation vote in the Senate before Nov. 3, 2020, Election Day. With a 53-47 Republican majority in the Senate, he appears to have enough votes, although the coronavirus outbreak among top Republican officials does potentially call into question the ability of the GOP to push through Barrett’s confirmation. But if Barrett is in fact confirmed to the court, “the Supreme Court will soon operate with a stout 6-3 conservative majority.” There ultimately may be little the Democrats can do to block the Barrett nomination.

Democrats are particularly outraged with McConnell’s plan to orchestrate a quick confirmation of Barrett. In February 2016, with the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia nine months before the 2016 election, McConnell and many of his Republican colleagues argued that a Supreme Court seat should not be filled during an election year. They refused to schedule hearings in the Senate to consider the nomination of President Barack Obama’s candidate for the vacant seat, Merrick Garland. Nonetheless, the Democrats do not now have the Senate votes to block the confirmation of Barrett.

What might the Democrats do? What are their options? One response would be statehood for Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. In the upcoming November elections, if Joe Biden defeats Donald Trump, and if the Democrats win control of the Senate and maintain control of the U.S. House, statehood for the District and for Puerto Rico is a real possibility. Let us consider some of the background issues for D.C. and P.R. statehood. And let us examine some of the political implications.

Background

For years, the motto of the District of Columbia has been “Taxation without Representation.” The residents of Washington, D.C. do not have voting representation in the U.S. House or in the Senate. People living in the District pay federal income taxes but have no say about how their tax dollars are spent. Washington, D.C. has a 2020 population of over 720,000 persons, larger than the populations of Vermont and Wyoming.

On June 26, 2020, the U.S. House voted 232-180, almost entirely on party lines, to establish Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital, as the 51st state. Under that proposal, the National Mall, the White House, Capitol Hill, and some other federal property would remain under congressional jurisdiction, with the rest of the land becoming the new state. If Biden beats Trump and if the Democrats win over the Senate, the Democrats could get D.C. statehood through the Senate, too, although the filibuster remains an obstacle. Biden has gone on record supporting statehood for the District.

Puerto Rico has been part of the U.S. since 1898, and its residents have been U.S. citizens since 1917. In 1952, Puerto Rico attained commonwealth status with local self-government. This involved a continuation of U.S. sovereignty over Puerto Rico and its people. Residents of Puerto Rico are not permitted to vote in presidential general elections, nor do they have voting representation in the U.S. House or Senate. Puerto Rico has a 2020 population of over 3 million residents, larger than the populations of 17 states and the District.

A referendum for statehood will be held in Puerto Rico on Nov. 3, 2020, the sixth time there has been a referendum on statehood. It will involve a straightforward yes/no question, for or against statehood for Puerto Rico. It is non-binding because the power to grant U.S. statehood lies with the U.S. Congress. If the referendum next month favors statehood, and if Puerto Rico submits a petition for statehood, and if Biden beats Trump, and if the Democrats win control of the Senate, then the House and Senate could pass a resolution authorizing statehood. We look next at some of the implications of the District and Puerto Rico becoming the 51st and 52nd states of the U.S.

Implications

What are the implications of D.C. and P.R. statehood for the distribution of Democrats and Republicans in the Senate? Every state has two senators. Currently the Senate has 45 Democrats, plus two Independents who caucus with the Democrats (Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Angus King of Maine), bringing the current total in the Democratic caucus to 47 members. There are 53 Republicans in the Senate.

If Washington, D.C. is granted statehood, its two new senators will certainly be Democrats. If Puerto Rico is granted statehood, it is possible that its two new senators will be Democrats, although there is not as much certainty as with the overwhelmingly Democratic District. According to Puerto Rico’s Resident Commissioner, Jenniffer González-Colón (R), most people “don’t know how conservative Hispanics and Puerto Ricans are, and they don’t know the number of Puerto Ricans who have fought in the armed forces, and they don’t know the platform of the Republican Party, which for the last 45 years has supported statehood.” Let us assume, thus, that statehood for both the District and Puerto Rico will result in three, maybe four of the new senators being Democrats.

As noted, there are currently 53 Republicans in the Senate and there are 45 Democrats, plus the two Independents who caucus with the Democrats. D.C. and Puerto Rico statehood will not occur in 2021 unless in the 2020 election Biden beats Trump and the Democrats gain control of the Senate. At a minimum, if Biden beats Trump, the Democrats would need a net gain of three seats to gain control of the Senate, resulting in a 50-50 distribution. Thereafter, if and when the District and Puerto Rico become states, the three new Democratic senators and one Republican senator would move Democratic control to 53-51. If all four new senators are Democrats, they would control the Senate 54 to 50.

Now let us look at the U.S. House. There are 435 seats in the U.S. House. Every state receives one seat automatically. The remaining 385 seats are then distributed according to the size of the populations of the states, using an apportionment method known as Equal Proportions. Given our discussions about Washington DC and Puerto Rico becoming the 51st and 52nd states, we ask now how these additions would change the House.

First, we believe that it is unlikely that the House will increase its number of seats beyond 435. Unlike the situation in the Senate, seat assignment in the House is a zero-sum game. If two new states are added, the first 52 seats will then go to each state, one per state. The remaining 383 will then be distributed according to the size of the state populations using the method of Equal Proportions. In the early years of our nation, the number of House seats actually changed every 10 years. Indeed, as the New York Times noted, “when the House met in 1789 it had 65 members … For well over a century, after each census Congress would pass a law increasing the size of the House. But after the 1910 census, when the House grew from 391 members to 433 (two more were added later when Arizona and New Mexico became states), the growth stopped.” We believe that owing to precedent, the number of House seats will not increase beyond 435. It has been well over 100 years since the size of the House stopped increasing in size. One exception to this “rule” occurred with the admission of Alaska and Hawaii in the late 1950s. For one session of Congress there were 437 seats (one each for Alaska and for Hawaii). However, with the results from the decennial census in 1960 the House reverted back to its basic number of 435 seats. So how will the distribution of the 435 seats change if the District and Puerto Rico become states?

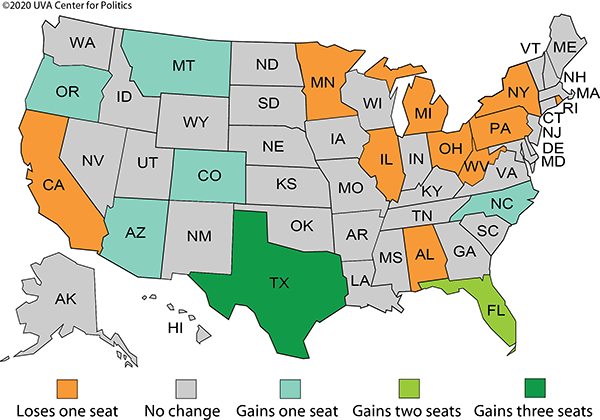

In our research we projected to 2020 the apportionment populations of the 50 states and then used the method of Equal Proportions to distribute among the states the remaining 385 House seats. In late July of 2020, we presented our apportionment results in Sabato’s Crystal Ball (see Map 1). We showed that 10 states are each projected to lose one House seat in 2020: Alabama, California, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia. And we showed that seven states are projected to gain House seats in 2020: three seats in Texas, two in Florida, and one each in Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon. How will this distribution change if the District and Puerto Rico become states?

Map 1: 2020 reapportionment projection

The District will be awarded the one automatic seat. But its 2020 population of around 720,000 persons is not large enough to warrant a second seat. Puerto Rico will also be awarded the one automatic seat. And its 2020 population of over 3 million inhabitants would result in it receiving second, third and fourth seats. Five of the 435 seats in the U.S. House will thus go to the District and to Puerto Rico. This means that five states would each receive one less seat in the apportionment.

However, if statehood occurs, it will likely occur after the 2020 apportionment of the House, perhaps in 2021 or 2022. Thus the House could temporarily increase its size to 440 with the additions of the District and Puerto Rico, and then go back to 435 with the 2030 apportionment. Or the House could undergo two 2020 apportionments, one in early 2021 without the two new states, and a second one in late 2021 or 2022 or thereafter with the two new states.

According to the results of our 2020 apportionment, the states in line to receive the 435th, 434th, 433rd, 432nd and 431st seats are, respectively, New York (its 26th seat), Florida (its 29th seat), Texas (its 39th seat), Montana (its second seat), and Illinois (its 17th seat). If the District and Puerto Rico become states, these five states would each receive one less seat.

In the 2016 presidential elections, three of these five states, Texas, Florida and Montana, voted Republican, while Illinois and New York voted Democratic. The three seats that the Republican states will lose to the District and Puerto Rico will likely become Democratic seats. The two that will be lost by New York and Illinois are likely to remain Democratic (although it’s sometimes hard to know with certainty precisely which party will be hurt or helped by reapportionment and redistricting in a given state). Still, similar to the situation in the Senate where the Democrats will gain three or all four of the new Senate seats if the District and Puerto Rico become states, the Democrats are likely to gain the three seats in the House that will be lost by the three Republican states, although, again, the political situation in Puerto Rico may be harder to predict.

If the Democrats win the 2020 presidential election and gain control of the Senate and retain control of the House, statehood for the District and Puerto Rico becomes a real possibility. Yes, Democrats are upset, indeed incensed, with Trump’s selection of Amy Coney Barrett as his nominee to fill the Supreme Court seat of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But they stand to gain a great deal with statehood for the District and Puerto Rico. Indeed, as a recent story in The Hill noted, the prospects of statehood for Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. have never been greater.

| Dudley L. Poston Jr. is an Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Texas A&M University, College Station. D. Nicole Farris is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Texas A&M University, Commerce. |