| Dear Readers: We are excited to feature a first-time Crystal Ball contributor today, UVA student Ethan Chen. He examines an interesting phenomenon in the 2020 House elections: a much more significant incumbency advantage for Republicans compared to Democrats.

— The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The 2020 House results were not merely due to a GOP advantage down-ballot. For open House races, Republicans only did slightly better on average than President Trump.

— House Republicans benefited from a significantly stronger incumbency advantage than House Democrats. This was the main reason for their performance.

— The historical anomaly is not incumbency being stronger for the Republicans, but the absolute collapse of the advantage for Democrats.

The GOP’s House incumbency edge

In the last election cycle, Democrats won a trifecta by the bare skin of their teeth. However, while both the presidency and the Senate were at times considered Toss-ups, the House was rarely considered to be in play. Yet Democrats lost 13 seats and nearly the House majority.

In one sense, this shouldn’t be that surprising — Joe Biden only won 224 House districts, similar to the 222 his party won in the House. Still, as the party with more incumbents, the incumbency bonus would’ve historically insulated more members from defeat. While many incumbent Democrats outran Biden, the benefit they received seemed dwarfed by the down-ballot overperformance of the GOP — not a single incumbent House Republican lost reelection last year, even as a few Republican-held districts crossed over to vote for Biden (or voted for Donald Trump by significantly reduced margins). Meanwhile, longtime Democratic overperformers like Ron Kind (WI-3) and Collin Peterson (MN-7) saw their crossover support diminish dramatically, to the point of losing (Peterson) or almost losing (Kind) reelection. So what exactly happened to incumbency in 2020, and how prevalent was the down-ballot Republican ticket split?

To figure out what happened, we’re going to answer the following question: was the effect of incumbency stronger for Republicans than for Democrats? While the answer to this might seem obvious — of course it was — keep in mind that incumbency might have nothing to do with this: Republicans might’ve similarly outran Trump with or without an incumbent. Thus, we must first address whether this was the case.

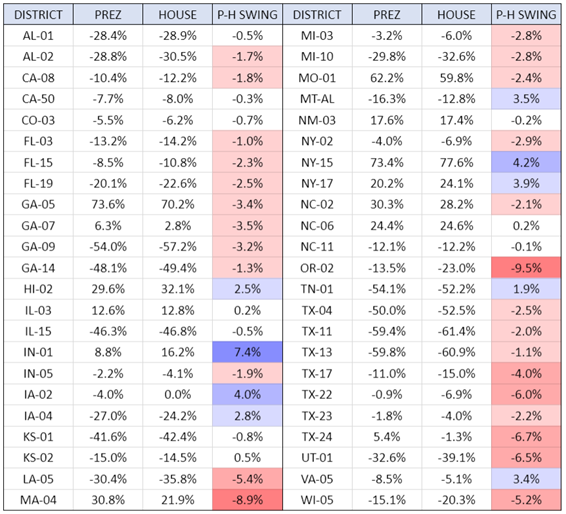

To do so, we shall establish a baseline — how did results in open House races compare to the top of the ticket? In 2020, there were 46 open House races contested by both parties — about a tenth of all the seats in the chamber. When comparing how districts voted for the House with how they voted for president, we see that Republicans outran Trump by an average of 1.4% in open House races. While this split might’ve made the difference in elections like TX-24 — a Trump 2016/Biden 2020 district that Republicans narrowly held — it’s not that large an advantage in the grand scheme of things. Simply not being Trump wasn’t the key booster of Republican fortunes last November.

Table 1: Presidential vs. House results in open House seats

Notes: This is likely not a representative sample: 36 of the 46 open seats both parties contested were previously held by Republicans. Democrats outperformed Biden in six of the 10 districts previously held by Democrats, but only six of 36 districts previously held by Republicans. Still, it’s the best we’ve got. This list also excludes a few open seats where there was not two-party competition in November.

Source: Daily Kos Elections

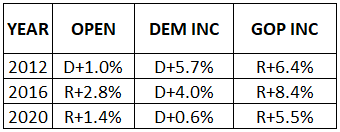

Now that we’ve ruled out the idea that incumbency didn’t matter, let’s take a look at what happened where incumbents were running. Similar to the previous calculation, we can also take an average of down-ballot overperformances when the opposing party challenged the incumbent. Doing so shows that while Democratic incumbents outran Biden by an average of 0.6%, Republican incumbents on average outran Trump by significantly larger 5.5%. Even taking into account the baseline — that the down-ballot was 1.4% more Republican than the top — the effect of incumbency was still twice as strong for the GOP than for the Democrats.

What this finding rules out is the idea that this was solely Republicans splitting their vote for Biden, only to vote party line for the rest of the ballot. If this were the case, there wouldn’t be such a stark difference between races with an incumbent and races without. For some reason, Biden voters were much more willing to split their ticket not simply for Republicans, but Republican incumbents, than the other way around.

Given this conclusion, another question thus arises: how much of a historical anomaly was this result? Split-ticket voting hit one of its all-time lows last November, with only 16 representatives winning districts carried by the opposing presidential candidate. Even so, did incumbency always benefit Republicans more than Democrats? To find out, the same analysis was conducted on the 2012 and 2016 elections.

Table 2: Presidential vs. House results in recent presidential election years

Notes: 2011 was a redistricting year, so most incumbents represented new districts in 2012. Excludes races where incumbents of both parties were on the ballot.

Looking in the context of the last decade, the true anomaly of 2020 becomes clearer. It’s not that the GOP’s incumbency advantage was greater, as that also was the case in both 2012 and 2016. It’s not that Republicans did better down-ballot — open races actually favored them less than they did in 2016. It’s not even the relative advantage that’s bigger — Republicans had a bigger incumbency advantage relative to open races in 2012. No, the true anomaly was that while Republicans saw a drop in their incumbency advantage, the Democratic advantage collapsed completely. In fact, in comparison to 2016, both parties saw a similar drop in their advantage, although Democrats suffered a way larger drop from 2012.

In hindsight, such a conclusion makes a lot of sense. The initial expectations of many were that Democrats would lose a few of their most vulnerable members, but overall would keep a sizable House majority. Imagine if the results were that all the Republican incumbents survived, but so did all but a few of the Democrats. People would’ve been surprised by the polling miss, but it would’ve felt more like an average result. However, it was the disproportionate downfall of Democrats that defined their down-ballot disaster.

For both parties, the final and most important questions are: why did this happen, and how can they cause/prevent a repeat occurrence?

For the why, one answer lies in the ever-increasing polarization in U.S. politics. Ticket-splitting has been on the decline for decades, and people of opposite parties are demonizing each other, unwilling to give even an inch. This has been reflected in outcomes such as the unnatural steadiness of President Trump’s and President Biden’s approval ratings, and how all but one Senate race last year went the same way the state voted for president. As such, many voters who may have once split their ticket for the incumbent no longer did so if they viewed the opposing party as evil, as President Trump and a lot of Democrats had framed the election. In addition, 2020 featured a surge of low-propensity voters, as seen by the historically high turnout of the election. Lower-propensity voters have been shown to be less tuned in to politics, and thus may not be as aware of their incumbent. Therefore, 2020 may have featured a surge of straight-ticket voters by virtue of being low-information voters.

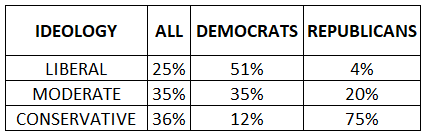

So that explains why ticket-splitting and the incumbency advantage dropped last year. What, then, explains why it was higher for Republicans than for Democrats? Well for starters, the Democratic coalition has long included many more self-described moderates than the Republican coalition. According to a Gallup survey from January, only 51% of Democrats are self-described liberals, in comparison to a whopping 75% of Republicans being self-described conservatives. Thus, it makes sense that members of the coalition with more moderates would be more prone to splitting their ticket, in this case giving the opposing incumbent the benefit of the doubt. In addition, there was a notable group of Biden Republicans this year — principally highly-educated Republicans who were turned off by and refused to vote for President Trump, but voted Republican for the rest of the ballot. The existence of these anti-Trump Republicans, who were a prominent feature of 2016 as well, is evident in suburban districts where Democrats near universally underperformed Biden, and definitely contributed to the advantage that Republicans had.

Table 3: Gallup polling of American political ideology

Source: Gallup

Finally, what can each party do about this? Some Democrats have pointed to the lack of in-person canvassing during the pandemic as a key reason for the disappointment down-ballot, while Biden himself has focused on passing popular legislation to restore bipartisan electoral support. On the other side, Republicans have largely doubled down on the culture wars and on keeping the electorate polarized, as it is largely to their benefit. Either way, this will be a factor both parties will be strategizing around in the coming election cycles, and will be crucial for whether Democrats can hold onto their congressional majorities.

| Ethan Chen is an elections analyst from New Jersey and a student at the University of Virginia. More of his analysis can be found on Twitter @ECaliberSeven. |