KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Across the South, some members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) overperform the presidential lean of their districts.

— Incumbents like G.K. Butterfield (D, NC-1), Sanford Bishop (D, GA-2), and Jim Clyburn (D, SC-6) show that incumbents who fit their districts can build durable local brands.

— Looking to November, to turn out black voters in the South — and beyond — national Democrats can learn from CBC members.

The subtle overperformance of some black southern Democrats

In 2008, a key ingredient to then-Sen. Barack Obama’s historic victory was his unprecedented support from African Americans. Though the African-American community has long been a cornerstone of the Democratic Party’s coalition, Obama inspired an unseen level of enthusiasm among minority voters. That enthusiasm, combined with the national political environment of that year, allowed him to carry previously Republican states like North Carolina and Virginia while cutting the Republican margin in other states like Georgia, which was last contested in 1996.

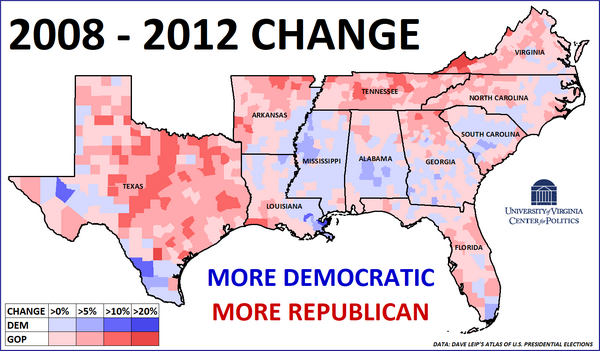

President Obama faced a closer race in 2012. While he lost ground across much of the country, he maintained his steadfast support among black voters. Despite his reduced margin nationwide, Obama improved his showing in heavily black counties, especially in the South (Map 1). This region, known as the “Black Belt” — which refers to the region’s soil, not its population — spans a wide swath of counties in every state across the Old Confederacy. Obama’s strength across this region was also because of his opponent. Mitt Romney — a patrician former governor of Massachusetts and Mormon — inspired little enthusiasm among evangelical whites, an essential part of the Republican coalition.

Map 1: 2008-2012 change in the Old Confederacy

When Obama was off the ballot in 2016, black turnout fell. Hillary Clinton simply couldn’t match Obama’s level of enthusiasm among this crucial group of voters. Clinton made gains in the more traditionally Republican suburbs in the South such as suburban Atlanta, Charleston, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle, but slumped elsewhere in the South.

Looking ahead to November, Democrats are eyeing two big electoral prizes: Georgia and North Carolina. Motivating black voters is essential to victory in these states, and the Democratic nominee would be wise to look to members of these states’ congressional delegations and learn from their successes.

Across the South, there are a handful of Democratic congressmen with unique appeal among both black voters and rural whites. Members such as G.K. Butterfield (D, NC-1), Sanford Bishop (D, GA-2), and Jim Clyburn (D, SC-6) outperformed Hillary Clinton in large part because they were able to win over rural white voters that backed Trump.

Together, the members of that trio represent districts that have common demographic factors. CityLab classifies each of these districts as “Rural-Suburban mix” — meaning they have large suburban and rural components but almost no dense urban areas. More importantly, given the diverse nature of the districts, their representatives must appeal to a broad array of constituencies.

North Carolina’s 1st District

Though its contours were altered for the 2020 cycle, NC-1 is located in northeastern North Carolina. Its western edge encroaches on the Raleigh metro area, and its eastern portion is anchored by several smaller cities: Rocky Mount, Greenville, Wilson, and Roanoke Rapids. Rep. G.K. Butterfield has represented this district in some form since 2004. Butterfield, a former judge, served on the North Carolina Supreme Court for two years. Gov. Mike Easley (D-NC) appointed Butterfield to the state Supreme Court in 2001 — the next year, he unsuccessfully ran for a full term on the court. Elected to the House in a 2004 special election, Butterfield quickly rose through the ranks of House Democratic Leadership, becoming Chief Deputy Whip in 2007.

When asked about Butterfield’s unique appeal, veteran North Carolina reporter Andy Specht suggested that “[Butterfield’s] success is probably due to name recognition in an area that’s socially conservative but so poor that it’s willing to support a candidate who says he’ll bring home government aid.” Indeed, on North Carolina’s new congressional map, NC-1 is the only Democratic-leaning district that voted in favor of the state’s 2012 referendum banning gay marriage. According to the Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey, 19% of the population in the 1st District lives below the poverty line.

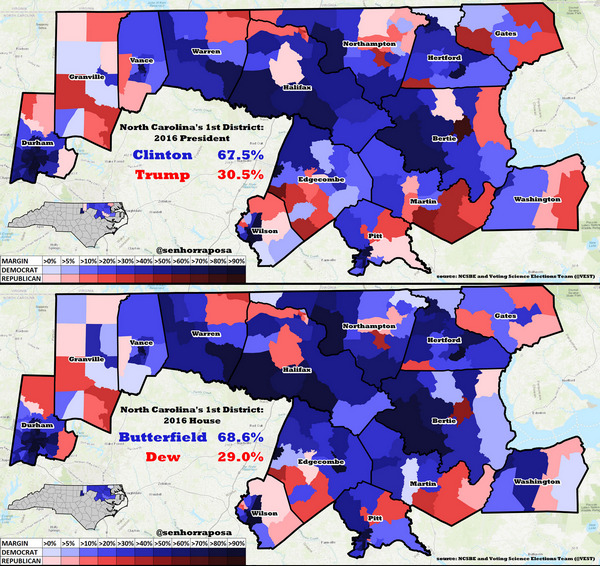

Map 2: NC-1 in 2016

In 2016, Butterfield outran Clinton by about 4% districtwide. His most acute overperformances came in the most rural counties — ancestrally Democratic Gates and Martin counties, on NC-1’s eastern border, stand out. Gates County, which voted Democratic for president from 1976 until 2016, is 33% black by registration; despite Trump’s comfortable 53%-44% advantage there, Butterfield held it 50%-48%. Throughout the district, there was little correlation between the racial composition of a county and where Butterfield most outperformed Clinton.

In November, Butterfield’s crossover will be tested, as he’ll be running in a redrawn seat that would have favored Hillary Clinton by a 54%-43% margin in 2016, instead of the overwhelming 37 percentage point spread that she would have carried his current seat by. Still, the Crystal Ball keeps NC-1 as Safe Democratic. Congressional Republicans currently do not hold any districts that gave Clinton a majority of the vote, and Butterfield has clearly built a strong brand in the area.

Georgia’s 2nd District

Located in southwestern Georgia, the 2nd Congressional District has been represented by Democrat Sanford Bishop since 1993. Political junkies will also note that President Jimmy Carter’s hometown, Plains, is located here.

Bishop, a Blue Dog, ranks as one of the House Democrats’ more conservative members. Bishop was one of 13 House Democrats to back the Bush Tax Cuts in 2001, and he has a mixed record on abortion rights. Bishop’s moderate views and attention to local issues has allowed him to cultivate a base of support that extends beyond the traditional Democratic coalition.

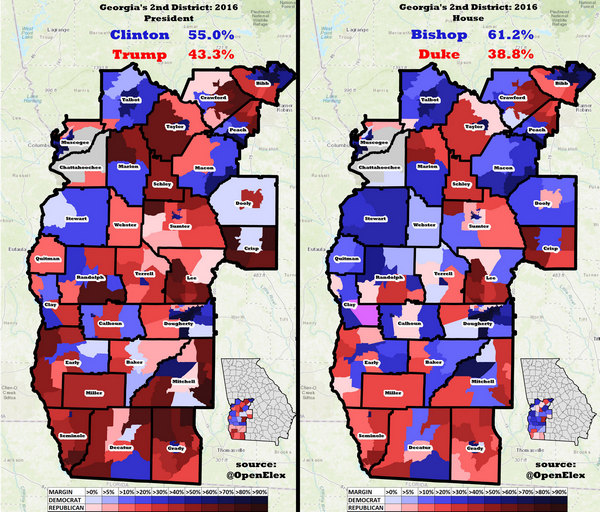

Hillary Clinton won the 2nd District 55%-43% in 2016 — which was down from Obama’s 59%-41% margin four years earlier — while Rep. Bishop won reelection 61%-39%. Bishop carried a number of small rural counties, such as Mitchell and Quitman, that went for Trump at the same time. Although earmarks are long since gone, Bishop’s position on the Appropriations Committee has allowed him to deliver for his district. A lifelong Baptist, Bishop regularly talks up his religious views and touts his A rating from the NRA. Bishop has successfully carved out a niche over several decades in politics by cultivating a moderate image and making the case to voters that he is one of them.

Map 3: GA-2 in 2016

Bishop outran Clinton throughout the district, winning eight Trump counties. Rural Quitman County went for Trump by 11% and Bishop by 17%, a 28% difference. Quitman saw a 20 percentage point swing between the last two presidential elections: it supported Obama by 9% then Trump by 11%. In 2018, Bishop went on to hold Quitman County by a much narrower 51%-49%, but it was a stark difference from the 12% loss that Democratic gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams took there.

South Carolina’s 6th District

Comprising much of south-central South Carolina is the Palmetto State’s 6th Congressional District. Home to Majority Whip Jim Clyburn since 1993, this was the sole district in the state to be represented by a Democrat from 2011 to 2019. A majority-black seat since the 1990 census, the district starts in the state capital, Columbia, spans to the Charleston metro area, and then takes in rural counties on the Georgia border. During his tenure in the House, Clyburn has championed rural and economic development for a district where 24% of the population is below the poverty level. Like Butterfield and Bishop, Clyburn regularly talks up his religious beliefs.

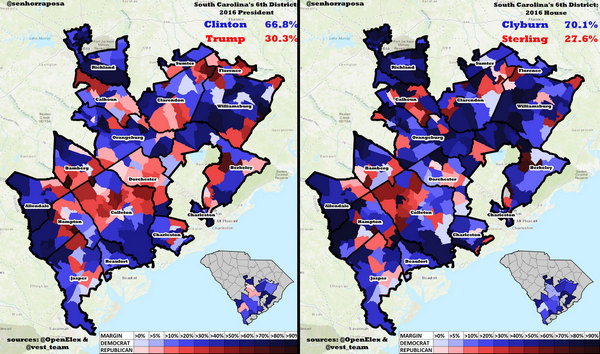

Map 4: SC-6 in 2016

Hillary Clinton carried this district 67%-30% in 2016 while Clyburn was reelected 70%-28%. Despite Clyburn’s status as one of the Democratic Party’s national leaders, he still maintains some crossover appeal. In 2016, three counties that are entirely or partially located in this district went for both Trump and Clyburn. As the Majority Whip, Clyburn is the third highest-ranking Democrat in the House — his lengthy tenure in House Democratic leadership doesn’t appear to have hampered his crossover support with the Republicans in his district.

G.K. Butterfield, Sanford Bishop, and Jim Clyburn are unique members of the House. Their years in politics have allowed them to build district political brands that distinguish themselves from other Democrats up and down the ballot. Why does this matter? All three of these men show that the Democratic nominee for president, hypothetically, can do better. These three know how to win white voters while also retaining an outsized share of the black vote.

With their credibility among Republican-leaning voters, the Congressional Black Caucus members campaigned heavily for Democratic candidates in the 2014 midterm elections. Despite the red wave that year, some U.S. Senate candidates in the South — such as the late Sen. Kay Hagan (D-NC) and Michelle Nunn (D-GA) — posted better margins in rural areas than what Hillary Clinton would go on to get two years later. As those states are likely to be closely contested this year, that difference could be crucial, although political change is occurring so rapidly that even the performances of Hagan and Nunn may be hard to replicate in some rural areas.

However, energizing black voters could pay dividends for Democrats in battlegrounds outside of the South. As Crystal Ball Associate Editor J. Miles Coleman, discussed in a recent article, the black vote will be a factor in Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, where the Democratic nominee could feasibly pick up an electoral vote.

| Drew Savicki is a freelance political cartographer based in the Raleigh, North Carolina region. On his Twitter page, @senhorraposa, he focuses on analyzing down-ballot races and electoral trends. |