| Editor’s Note: This is the first of two issues of the Crystal Ball this week. We’ll be back Thursday with our regularly-scheduled issue. |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— President Trump’s position has been perilously weak for a month and a half.

— With Joe Biden’s national lead around eight to 10 points, there is a possibility that he could compete for some usually Republican states.

— We are moving seven states from Safe Republican to Likely Republican.

— Our current ratings represent something of a hedge between a Trump comeback and Biden maintaining or expanding his large national lead.

— We also are moving the Missouri gubernatorial race from Likely Republican to Leans Republican.

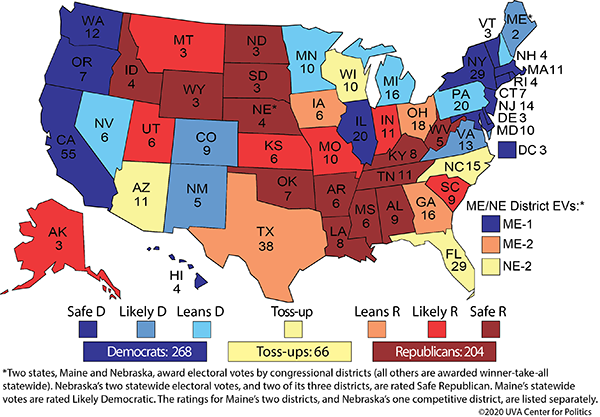

Table 1: Crystal Ball Electoral College rating changes

Table 2: Crystal Ball gubernatorial rating change

Map 1: Crystal Ball Electoral College ratings

The Electoral College fringe expands

We are now about six weeks into a downturn in Donald Trump’s polling numbers.

It’s worth thinking about the ramifications of this change if it endures.

In the RealClearPolitics average of national approval polling, Trump went from about early December to late May without ever dipping below -10 in net approval (approval minus disapproval). He has spent every day since June 1 at or below -10 net approval, and he’s currently at about -15.

Joe Biden’s national polling lead over Trump during May was in the four-to-six-point range. That was a decent lead, but not one that suggested Biden was a towering favorite, particularly because Trump was able to win in 2016 without winning the popular vote. But since early June, Biden’s lead has ballooned to the eight-to-10-point range. He has also enjoyed healthy leads in many polls of the most important swing states, like Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

The bottom line here is that the nation is in a state of terrible crisis, and the public has, at least for now, judged the president’s responses to both coronavirus and protests of racial inequalities in policing to be lacking.

In an ABC News/Ipsos poll released Friday, 67% of respondents disapproved of Trump’s handling of coronavirus and of race relations.

2020 is shaping up to be a bad year in American history, which Republican lobbyist Bruce Mehlman illustrates in his latest look at the political environment. It is not the kind of year when one wants to be an incumbent running for reelection, and a majority of the public appears to believe that this president is not meeting the moment.

A few weeks into the public health crisis, we explored the possibility of Trump being the second iteration of Jimmy Carter, whose reelection bid fell apart among myriad crises in 1980. Since then, the Trump-as-Carter scenario has grown even more plausible.

There is time for the situation to change — as we wrote a few weeks ago, we want to see where things stand after the conventions, around Labor Day. But Trump is extremely unlikely to win if the polls continue to look the way they do now. And if these numbers represent a new normal, we need to account for the possibility that this election won’t be particularly close, and that new states may come into play. In other words, if the national picture remains bleak for Trump, then the slippage he’s seen from earlier this year wouldn’t just be limited to a handful of swing states.

Over the past few weeks, there have been some interesting little nuggets here and there about the map expanding into red turf. The very well-sourced New York Times trio of Maggie Haberman, Jonathan Martin, and Alexander Burns recently reported that internal Republican data showed Trump with only a small lead in Montana and trailing in Kansas, two states that Trump carried by about 20 points apiece in 2016 (both have competitive Senate races, too).

Enterprising members of the #ElectionTwitter community spearheaded a fundraising campaign to poll under-polled states: Public Policy Polling, the Democratic pollster, stepped up and polled Alaska and Montana on their behalf, with the money raised going to charity. Trump was up 48%-45% in Alaska and 51%-42% in Montana. (The #ElectionTwitter polling project remains underway, and we have supported them and we encourage others to as well at their GoFundMe page.)

Democratic pollster Garin-Hart-Yang had Biden up two points in Missouri, a 19-point Trump state; an earlier poll for Missouri Scout conducted by Remington Research, a GOP firm, had Trump up eight. On Monday, polling from Saint Louis University/YouGov had Trump up by a similar 50%-43% margin.

A UtahPolicy.com/KUTV 2 News poll of Utah had Trump up just 44%-41% there in late May, although the pollster (Y2 Analytics) later re-weighted the poll by education, which suggested a lead for Trump more in the six-to-10-point range, depending on which weighting was used (the Y2 post includes a thoughtful discussion of education weighting, an important factor in polling and something that might have contributed to some Democratic bias in state polls in 2016).

One other caveat comes from friend of the Crystal Ball Dan Guild, who has noticed that in the last three elections, some summer polling has seriously overstated eventual November Democratic performance in red states. That may be a factor now.

But Trump’s position is weak enough in mid-July that we have to concede there are some signs of competitiveness in states that were not competitive in 2016. This sort of thing can happen when the overall election is tilted toward one side over the other, which is the state of play at the moment and the advantage Biden currently holds.

If Trump were up by 10 nationally, we might be moving Safe Democratic states that Hillary Clinton won in the low double-digits, like Delaware and Oregon, into more competitive categories.

More to the point, we continue to rate states like Colorado, New Mexico, and Virginia as Likely, not Safe, Democratic. That’s despite it being hard to imagine Trump carrying any of them, even if his position dramatically improves.

So we’re moving seven Safe Republican states to Likely Republican: Alaska, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, South Carolina, and Utah.

Do we think Biden will win these states? Not really. In all likelihood, these red states are going to vote for Trump, and not just by a few points.

But could one or more flip if Biden wins decisively in November? Possibly. Let’s remember: A “Likely” rating still means we see one side — in this case, the Republicans — clearly favored in a state. We just don’t feel 100% certain about these states in the event of a lopsided election.

Our current electoral map represents something of a hedge between Trump cutting markedly into Biden’s lead versus Biden maintaining his current edge or even expanding it.

In the former scenario, all of these states we’ve moved into Likely Republican would move back into the Safe Republican camp, and states like Michigan and Pennsylvania (which we rate as Leans Democratic) as well as Toss-ups like Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, and Wisconsin could all be on the razor’s edge. These six states remain the core battlegrounds that seem likeliest, collectively, to decide the election.

In the latter scenario, where Biden continues to do very well, most or all of those core battleground states would be more like Leans Democratic (or even Likely, at least in some cases); Leans Republican states like Georgia, Iowa, Ohio, and Texas would be more like Toss-ups; and some of the states we’ve flagged in today’s update could be in play.

As it stands now, our ratings account for both of these scenarios.

We think we’ll get more clarity about which scenario is more likely following the conventions — whatever the conventions actually look like. Even with 2020’s scaled down, undramatic, and overshadowed conventions, voters and media see them as departure points into the general election. Casting a ballot is no longer just on the distant horizon. It’s a reality that will firm up people’s choices — and our ratings.

P.S. Missouri governor rating change

While Missouri still seems very likely to vote Republican for president, a reduced margin could give Democrats a chance to truly compete against Gov. Mike Parson (R-MO). We’re moving the Missouri gubernatorial race from Likely Republican to Leans Republican.

Parson is running for his first elected term as governor. He was elected as lieutenant governor in 2016, defeating former Rep. Russ Carnahan (D), scion of the famous Missouri political family, by about 11 points. He was elected separately from Eric Greitens (R), who won the gubernatorial race but had to resign about a year and a half into his term because of scandal. Parson, a longtime legislator before becoming lieutenant governor, has had a smoother time in office than his predecessor, who made very few allies in Jefferson City.

Still, Parson is an unelected incumbent, and sometimes those kinds of incumbents don’t have the same incumbency benefit that elected ones do. Polls have shown Parson ahead, although the most recent one, by Saint Louis University/YouGov, only had him up 41%-39% over state Auditor Nicole Galloway (D) — other polls have had Parson up by more, though, including the Democratic poll cited above that had Biden implausibly leading Trump by two points (Parson was up 47%-40% in that poll, conducted for Galloway’s campaign). Galloway won a full term as state auditor in 2018 after then-Gov. Jay Nixon (D) appointed her to replace Tom Schweich (R), who took his own life in 2015. Galloway is about the strongest candidate Democrats could have mustered in Missouri, a border state where Republicans have been ascendant over the past decade.

Down-ballot Democrats are often able to perform better than their party’s presidential candidates in states like Missouri. In 2012, when Barack Obama lost Missouri by nine points, Democratic incumbents won both the gubernatorial and Senate races. In 2016, under the strain of Hillary Clinton’s 19-point statewide loss, Democrats lost the open governorship, although then-Missouri Secretary of State Jason Kander (D) came within three points of unseating Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO). Perhaps if Clinton had been able to do a little bit better, Kander could have won.

It may be that in some of these red states, Biden can improve Democratic presidential numbers to look more like 2012 than 2016 — in other words, losing by more like 10 instead of 20. That sort of improvement, if it happens, could have down-ballot consequences.