KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— This is the second part of our history of presidential-Senate split-ticket results, from World War II to now. This part covers the mid-1980s to present, a timeframe that started with many instances of split results and ended with hardly any at all.

— In 1984 and 1988, amidst large GOP victories at the presidential level, more than a dozen Republican-won states sent Democrats to the Senate both years.

— The 1990s, when Democrats were successful at the presidential level, split-ticket voting tended to benefit Republicans in the Senate, making the decade an exception in the postwar era.

— In the 2000s, Democrats were back to benefitting from the split-ticket dynamic, first under a Republican president, George W. Bush, then with a Democrat, Barack Obama.

— Montana, a state which Senate Democrats are defending this year in a Toss-up race, is the state that has split its ticket most often in the postwar era. And almost every state has split its ticket at least once during that time.

A history of split presidential/Senate outcomes, continued

This week, we’ll continue our look at the history of postwar split-ticket outcomes between presidential and Senate races. Last week, in Part One, we examined the years spanning from 1948 to 1980. Now, we’ll start with 1984, the year that then-President Ronald Reagan was easily reelected, and go up to 2020, when now-former President Donald Trump was not as successful in his reelection bid.

In Part One, the number of split-ticket states tended to increase as we went further along chronologically. In what follows, the opposite trend will take hold, although there were still a critical number of split-ticket results most cycles.

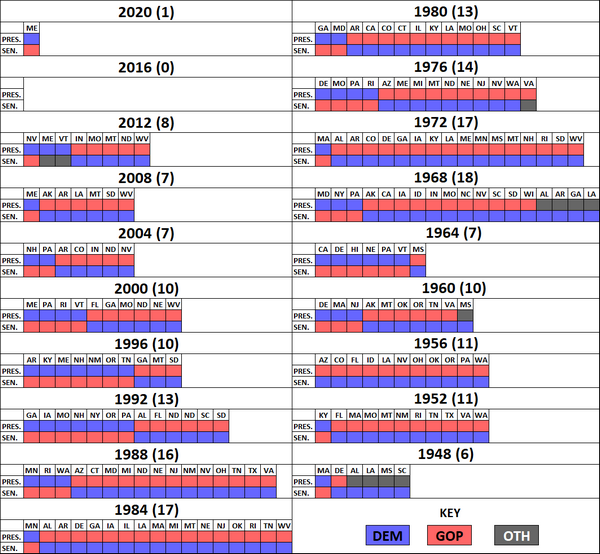

As a refresher, Table 1 lists all the split-ticket outcomes in the postwar era.

Table 1: Split presidential/Senate outcomes by year, 1948-2020

Sources: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, Crystal Ball research, Wikipedia.

1984

We begin this second part of our series with 1984, a year that seems like a nearly perfect copy of 1972. In both cases, Republican presidents were reelected in 49-state landslides. Both cycles also featured 17 split-ticket races. Lastly, the sole state that Democratic presidential nominees carried (Massachusetts in 1972 and Minnesota in 1984) reelected Republican senators.

Of the 16 states that Senate Democrats won, three were flips. In Iowa, prairie populist Rep. Tom Harkin (D) handily defeated first-term Sen. Roger Jepsen (R). Jepsen, who campaigned as conservative Christian, was hurt when it was revealed he visited a spa that was later closed over prostitution. In next-door Illinois, veteran Sen. Charles Percy (R) found himself pushed by the right in his primary and struggled to get his footing back in the general election and lost to downstate Democratic Rep. Paul Simon (D). Compared to 1980, Reagan’s margins dropped in much of the Farm Belt, encompassing Iowa and much of Illinois, which probably worked against down-ballot Republicans there. Finally, in Tennessee, Republican Majority Leader Howard Baker retired and Rep. Al Gore (D), then representing Middle Tennessee, easily won the open seat.

While Reagan’s coattails were limited, it would be hard to argue that, on balance, his presence at the top of the ticket wasn’t an asset for Republicans. His 21-point win in Kentucky likely helped push now-Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell over the top (this was the sole Democratic-held state that Republicans flipped that year). On Wednesday, McConnell announced he would step down as the chamber’s GOP leader later this year, ending his nearly two-decade tenure in that post. Similarly, Democrats’ biggest offensive disappointment of the 1984 cycle was in North Carolina, as then-Gov. Jim Hunt (D) narrowly lost to Sen. Jesse Helms (R), who repeatedly tied himself to Reagan on the campaign trail.

1988

With Reagan termed out in 1988, Vice President George H. W. Bush, kept the White House in GOP hands for a third term. But, as with 1984, a strong Republican showing at the presidential level—Bush won the popular vote 53%-46% and managed an Electoral College landslide—did not prevent Democrats from gaining in the Senate.

Senate Democrats won 13 states that Bush carried. The lion’s share of these featured personally popular incumbents. In Texas, for instance, Sen. Lloyd Bentsen (D), was Democrats’ nominee for vice president but was also allowed to seek a fourth term (in 2008, Joe Biden, whose Senate seat was up, did the same thing). As the Dukakis/Bentsen ticket lost Texas by 13 points, Bentsen was reelected 59%-40%. Bentsen’s win would mark the last time Texas voters sent a Democrat to the Senate.

A sign of today’s electoral polarization, and one that has worked against both parties in recent cycles, is that popular former governors have struggled to win Senate seats in states that usually vote for the other side’s presidential party. Former Gov. Larry Hogan’s (R-MD) Senate run gave us reason to discuss this trend earlier this month. But in 1988, this was not the case. Three of the four Democrats who flipped seats that year were sitting or former governors: Bob Kerrey in Nebraska, Richard Bryan in Nevada, and Chuck Robb in Virginia. Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis did not break 40% in any of those three states. The fourth Democratic flip was one that featured some ideological line-blurring: in Connecticut, state Attorney General Joe Lieberman, a conservative Democrat, won 50%-49% to deny Sen. Lowell Weicker, a liberal Republican, a fourth term.

Next door, in Dukakis’s best state, Rhode Island, a liberal Republican did better: Sen. John Chafee (R) won by about 10 points. In Minnesota, centrist Republican David Durenberger, who would, later in life, endorse Democrats with some regularity, won even more comfortably. Lastly, in the closest Dukakis-won state, Washington, former Sen. Slade Gorton (R) narrowly staged a comeback. Gorton’s 1980 win was part of Senate Republicans’ 12-seat gain that year but, like several of his classmates, he was swept out in 1986, when Democrats regained the Senate.

1992

1992, which is the 12th cycle we’ve examined so far in this series, was only the second up to this point in which the ticket-splitting dynamic benefitted Senate Republicans: six Democrats were elected in Bush-won states while Republicans won seven states that Bill Clinton carried. Prior to 1992, only the 1964 LBJ landslide featured more Republicans than Democrats winning crossover seats.

The Democrats’ crossover seats were concentrated in the South and the Dakotas. In the reddest of these, South Carolina, the long-serving and quotable Fritz Hollings won a fifth full term. Alabama, Florida, and South Dakota all reelected Democrats who had each, in 1986, defeated Republicans who were swept in during the 1980 Reagan wave (the most conservative of those Democrats, Richard Shelby, would become a Republican after the GOP’s Senate takeover in 1994).

North Dakota, meanwhile, was a bit of an odd situation. Kent Conrad, another 1986 winner, pledged that he wouldn’t run for his seat again if the national debt had not been significantly reduced during his term. Conrad planned on retiring, but when the state’s other seat opened up after the death of longtime Sen. Quentin Burdick (D), Conrad announced he’d run for that seat. At-Large Rep. Byron Dorgan (D), who never had reelection trouble, slid seamlessly into Conrad’s seat in the regular election while Conrad easily won a December special election to serve the remainder of Burdick’s term.

The sole split-ticket state that changed hands was in the South. On Election Day, Sen. Wyche Fowler (D), yet another first-term Democrat from 1986, led Republican Paul Coverdell by a 49%-48% vote as Clinton carried the state by half a percentage point. But with Georgia’s runoff law in place, Coverdell won 51%-49% in a second round that was held later that month (so, as with the North Dakota special, we are calling this a split-ticket result even though it wasn’t concurrent with the November election).

In the heartland, Iowa, which was one of the most Democratic states in the 1980s, was safe territory for Sen. Chuck Grassley: after winning his seat in 1980, he was reelected by 32% in 1986 and more than 40% in 1992. One state south, Sen. Kit Bond, a former governor, was the sole Republican to win a statewide contest in Missouri that year.

Out west, Democrats finally convinced nine-term Rep. Les AuCoin to run statewide. But AuCoin only barely emerged from a nasty (and close) primary and lost 52%-47% to Sen. Bob Packwood (R). Packwood won what was his fifth term, but would resign in 1995, as he was faced with allegations of abusive behavior towards women. On the other side of the country, Arlen Specter (R-PA) and Al D’Amato (R-NY—this story has been updated from an earlier version to correct D’Amato’s state), who were both 1980 winners, held on with pluralities in their large states. Finally, staying in the northeast, Gov. Judd Gregg (R) was elected to the Senate with a similar 48%-45% plurality.

1996

When Clinton came up for reelection, the split-ticket dynamic was even more in favor of Republicans. As with 1992, Republicans won Senate seats in seven Clinton states, but only three states that backed his opponent, former Sen. Bob Dole, elected Democrats. With this, the Clinton era was a rough patch for Senate Democrats.

In what must’ve been an embarrassing result for the White House, Republicans picked up an open seat in the president’s native Arkansas. Next door, Republican Fred Thompson, who won then-Vice President Al Gore’s old Tennessee Senate seat in a 1994 special election, won a full term with more than 60%. Another Democratic disappointment in the Outer South was Kentucky. After single-digit margins in his first two races, McConnell won a third term by a solid 55%-43%—his opponent was future Gov. Steve Beshear (D). Just beyond the western edge of the Old Confederacy, GOP Sen. Pete Domenici, who was first elected in 1972, remained popular in New Mexico.

As they did in 1992, the northern tier states of Oregon and New Hampshire split their tickets for down-ballot Republicans. Coincidentally, in both states, Republicans with the surname “Smith” won with nearly identical pluralities: Gordon Smith, a moderate, in Oregon, and Bob Smith, a conservative, in New Hampshire. Another Republican who won with a plurality was Maine Republican Susan Collins, who was coming off a gubernatorial loss in 1994. Collins, as we’ll see later, would steadily increase her margins until she was pressed, but still won, in 2020.

Democrats did manage to flip a Dole-won state. With then-South Dakota At-Large Rep. Tim Johnson’s 51%-49% win over three-term Sen. Larry Pressler (R), Democrats could claim all four Dakota Senate seats. In Montana, three-term Sen. Max Baucus (D) got a serious challenge from Lt. Gov. Denny Rehberg (who we’ll see more of later), but prevailed 50%-45%.

Finally, like 1992, Georgia makes Table 1, although the circumstances were different. With the runoff law repealed (it has since been put back into place) Georgia Secretary of State Max Cleland (D) held this open seat for the Democrats with 49% as Dole flipped Georgia at the presidential level. So Georgia went from a Clinton/Republican state in 1992 to a Dole/Democratic state in 1996.

2000

As the White House fell back into GOP hands in 2000, the split-ticket dynamic “reverted” to normal: Democrats won six of the cycle’s 10 crossover seats en route to netting seats and creating a 50-50 tie in the Senate.

All four of the Gore/Republican states were located north of the Mason-Dixon line. In Pennsylvania, Sen. Rick Santorum, who won his seat in the anti-Clinton 1994 midterm, expanded his margin against an underfunded challenger. Santorum, a social conservative from the Pittsburgh area, posted healthy margins in the Philadelphia collar counties. In New England, Maine’s Olympia Snowe and Vermont’s Jim Jeffords won with close to 70%. Snowe was the most moderate member of the 1994 GOP freshman class while Jeffords would leave the GOP in 2001—though he became an independent, he caucused with Democrats, giving them a 51-49 majority that Republicans would flip in the 2002 midterm. Finally, Rhode Island’s Lincoln Chafee was appointed in 1999 after the death of his father, the long-serving John Chafee (R), a liberal. In Gore’s best state, the younger Chafee pledged to be a senator in the mold of his late father and won a full term.

Democrats flipped two Senate seats in close Bush-won states: Florida and Missouri. In the latter, term-limited Gov. Mel Carnahan (D) challenged first-term Sen. John Ashcroft (R). Weeks before the election, a plane carrying Carnahan crashed, killing him. Gov. Roger Wilson (D), who assumed the state’s top office, let it be known that if Carnahan won (his name was already printed on ballots), he would appoint the late governor’s widow to the Senate. That is exactly what happened. In Florida, the state that (in)famously decided the presidential election, then-state Treasurer Bill Nelson (D) beat Orlando-area GOP Rep. Bill McCollum 51%-46% for an open seat.

Democrats won two other races thanks to popular former governors. In Nebraska, former Gov. Ben Nelson (D) won a Senate seat on his second try. In Georgia, the aforementioned Coverdell was reelected in 1998 but died in 2000. Former Gov. Zell Miller (D) was appointed to the seat and won an election to serve out the term. As governor, Miller was a mainstream Democrat, but he would go on to endorse Bush in 2004. After Miller’s 20-point win, Democrats would not win either of Georgia’s seats until the 2021 runoffs.

At the presidential level, West Virginia shocked pundits by backing Bush—but as usual, Sen. Robert Byrd (D) had little opposition. Kent Conrad, still popular in North Dakota, won his third full term in one of Bush’s best states.

2004

In 2004, the number of split-ticket outcomes fell to single-digits for the first time since 1964. Still, even as Republicans had what could be called a banner year—as Bush was reelected with 51% of the popular vote, the GOP expanded its majorities in both chambers of Congress—Democrats still managed to claim more crossover Senate seats.

The sole split-ticket seat that changed hands was Colorado. State Attorney General Ken Salazar, who at the time was Colorado’s only statewide Democratic official, beat beer magnate Pete Coors (R). In addition to winning crossover votes in the Denver suburbs, Salazar ran especially well in the Hispano-heavy southern counties.

Another strong western state result for Democrats was Nevada. After nearly losing his seat in 1998, Sen. Harry Reid (D) did not draw a formidable challenger in 2004. Outside of the state’s two large counties, Clark (Las Vegas) and Washoe (Reno), Reid nearly carried the sparsely populated “cow counties,” which collectively went 2-to-1 for Bush. After the election, Reid would replace South Dakota’s Tom Daschle, who lost his seat that cycle, as leader of the Senate Democrats.

North Dakota kept up its streak of electing Democrats, giving Dorgan close to 70%. In 1998, Arkansas and Indiana first elected Democrats Blanche Lincoln and Evan Bayh with 55% and 63%, respectively—both basically replicated those numbers six years later. Regionally, Lincoln’s reelection stood out, as, elsewhere in the South, Republicans picked up five Senate seats in Bush-won states.

At the presidential level, Sen. John Kerry, a New Englander, flipped New Hampshire back into the blue column. But the aforementioned Sen. Judd Gregg had an underfunded opponent and won 2-to-1. Finally, in Pennsylvania, moderate Republican Arlen Specter only barely survived a primary with then-Rep. Pat Toomey (who would replace him in 2010) but his independence was more of an asset in the general election.

2008

In 2008, the number of split-ticket states remained at seven. In what was arguably the last blue wave presidential election, Democrats won Senate seats in six states that Barack Obama lost while Republicans claimed one split-ticket result.

In Alaska, Sen. Ted Stevens, a Republican who had served since 1968, came under federal investigation in 2007 for corruption. Stevens was initially convicted right before the 2008 election—although the conviction was later thrown out at the request of the Justice Department because of prosecutorial misconduct. Stevens lost his seat to Anchorage Mayor Mark Begich (D) by a percentage point. Begich’s victory represented the last time a challenger defeated an incumbent to produce a split-ticket result.

The two states that trended most against Obama at the presidential level, Arkansas and Louisiana, reelected Democrats. In the former, first-term Sen. Mark Pryor (D), along with all four members of his state’s House delegation that year, had no major party opposition. In Louisiana, Sen. Mary Landrieu, who cobbled together slim majorities in her 1996 and 2002 races, won a third term by a relatively comfortable 52%-46% over current Sen. John Kennedy (R), a Democrat who rather transparently changed parties ahead of the race. Voters seemed to reward Landrieu for her work spearheading the recovery after Hurricane Katrina.

National Republicans did not seriously target three other entrenched red state Democrats: Montana’s Max Baucus, South Dakota’s Tim Johnson, and West Virginia’s Jay Rockefeller, all of whom cleared 60% of the vote.

In Maine, Democrats recruited a credible candidate against Collins (R) and tried to link her to the unpopular Bush. But she was reelected by 23 points. We may also note that while all of the McCain/Democratic seats flipped when they were next up, in the 2014 midterm, Collins remains in office.

2012

As Obama was reelected by a reduced margin, the number of split-ticket states inched up—sort of.

We’re including both Maine and Vermont on Table 1, as they were blue states that sent independents to the Senate. But in the former, though he did not announce his preference until after the election, there was not much question as to which side former Gov. Angus King would join (he endorsed Obama in 2008). And as for the latter, Sen. Bernie Sanders had been caucusing with Democrats since his 1990 election to Congress.

Though Obama carried Indiana and only barely missed Missouri in 2008, his campaign did not give those states much attention in 2012—but both elected Democrats to the Senate. In both, Democrats were aided by gaffe-prone GOP nominees. Veteran Indiana Sen. Dick Lugar (R) was trounced in his primary by a Tea Party challenger who went on to lose to then-Rep. Joe Donnelly (D). In Missouri, Sen. Claire McCaskill (D) famously played in the GOP primary to pick her opponent, then-Rep. Todd Akin. In a post-primary interview, Akin was asked about his views on abortion and came up with the phrase “legitimate rape.” McCaskill won by 16 points.

In Montana, the aforementioned Rehberg, now in Congress, ran against Sen. Jon Tester (D) but lost by the same 49%-45% that Baucus beat him by in 1996. Next door in North Dakota, when Conrad retired, Rep. Rick Berg (R) entered the race as a strong favorite but was outworked by former state Attorney General Heidi Heitkamp (D). Finally, in a 2010 special election, Republicans made some effort to win Byrd’s old seat but came up 10 points short to then-Gov. Joe Manchin (D). Manchin, in office, had positive approval ratings and beat the same opponent by 25 points.

On the Republican side, appointed Sen. Dean Heller (R) won a full term in Nevada. Though he had some unique strength in the Reno area, he was helped by a weak Democratic nominee and a high third-party showing in the state. Heller won with the same 46% that Mitt Romney took in Nevada.

Just as the 2014 election wiped out most of the 2008 crossover states on Table 1, the 2018 election was not kind to the 2012 crossover members. Heller, along with Donnelly, Heitkamp, and McCaskill, were defeated in 2018.

2016

Much to the disappointment of those of us who study political coalitions, there were no crossover Senate results in 2016. That said, several states saw notable internal coalition differences. For instance, both Sens. Ron Johnson (R-WI) and Pat Toomey (R-PA) ran markedly ahead of Donald Trump’s numbers in the suburban parts of their states but generally behind him in the rural areas. Similarly, it was perhaps a sign of things to come that, in Arizona, Trump ran nearly 10 points behind the late Sen. John McCain (R).

2020

As we’ve mentioned before, in 2020, the only state that split its ticket was Maine, where Collins won 51%-42% as Joe Biden won the state by a similar margin. We may note that, on paper, Collins margin was 9 points, but under the state’s ranked-choice system, Lisa Savage, a liberal third party candidate, told her supporters to rank Democratic nominee Sara Gideon second—so there were probably many Savage voters who assumed, had ranked choice kicked in, they’d be voting for Gideon. But Collins won outright.

One “almost” from 2020 was Georgia. As Biden narrowly carried the Peach State in November, then-Sen. David Perdue (R) took 49.7% to now-Sen. Jon Ossoff’s 48.0%. Had there been no runoff law in place, Perdue would still be a senator (the other Senate race, a special election eventually won by Democrat Raphael Warnock concurrently with Ossoff on Jan. 5, 2021, featured an all-party jungle primary for the first round of voting).

We’d also try a bit of a thought experiment in North Carolina. As we explored shortly after the 2020 election, we think Sen. Thom Tillis (R) was able to hold on, above all, because Biden didn’t carry the state. In fact, North Carolina and Wisconsin are two currently-marginal states that each made their sole appearance on Table 1 way back in 1968. But the last Democratic presidential nominee to carry the state was Obama, in 2008—he did so by three-tenths of a point. Cal Cunningham, Tillis’s Democratic opponent, ran four-tenths of a point behind Biden. So, had Biden matched Obama’s 2008 margin, Cunningham would have still lost, for another split ticket-result.

Conclusion

Throughout the postwar era, there have been nearly 200 instances of split-ticket presidential/Senate outcomes. During that timeframe, all but three states have split their tickets. Those exceptions were Kansas, Utah, and Wyoming, three smaller, solidly GOP states. Kansas, which has not sent a Democrat to the Senate since the days of Franklin Roosevelt, only voted Democratic for president once in the postwar era, in 1964—it did not have a Senate seat up that year. Utah and Wyoming did produce a few straight-ticket Democratic outcomes in 1948 and 1964, but since then, they have been firmly in the Republican camp.

On the other extreme, the state that has split its ticket most frequently is Montana, and it has always been to the benefit of Senate Democrats. This is good news for Tester, who, as we have alluded to earlier is in a Toss-up race to keep his seat in a state that Trump will likely carry by double-digits. We may add that, in some less promising news for Democrats, Ohio, where Sen. Sherrod Brown (D) is in another red state Toss-up race, has split its ticket in only three postwar presidential elections, less than the average of 3.9 times per state.

Finally, just because a state has split its ticket in favor of one party or another in the past doesn’t mean that it is guaranteed to continue to do so. West Virginia, for instance, produced 5 split-ticket results favoring Senate Democrats on Table 1. But with Manchin retiring, by the beginning of next year, Republicans will very likely hold both of the state’s Senate seats for the first time in over 60 years.

Part of the reason we wanted to go through this history was just to illustrate how much different Senate elections in presidential years have become—and how much more closely tied those results have become in recent years.