KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In North Carolina’s hotly contested Senate race last year, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) narrowly won reelection against a scandal-plagued opponent, former state Sen. Cal Cunningham (D-NC).

— Had Cunningham’s candidacy not been weighed down by a personal affair, he may have still lost. Indeed, a Tillis win was consistent with other results around the country and in the state.

— Still, Cunningham certainly didn’t benefit from his scandal, and it very likely cost him votes.

Democrats fumble away a winnable race… or did they?

It is one of the great what-ifs of the 2020 election cycle: absent a late-breaking scandal, would Democrats have won North Carolina’s Senate race? Even though Democrats won the Senate anyway, thanks to twin victories in Georgia’s early January Senate runoffs, the question merits exploration. For one thing, every Senate seat is vital to both sides in an evenly-divided chamber. And at a time when elections seem more nationalized than ever, it may be that the foibles of candidates matter less.

During the 2020 cycle, North Carolina’s Senate contest was seen as a must-win for Senate Democrats. In this light red state, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) looked vulnerable. He was never particularly popular, and six years earlier, he was initially elected in what was an overwhelmingly favorable year for Republicans. Though he was the incumbent in 2020, the thinking seemed to be that he’d have a close race in a more neutral, or even pro-Democratic, environment.

Leading up to the March 2020 primary, national Democrats took the race seriously: the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee endorsed former state Sen. Cal Cunningham (D-NC). With service in the U.S. Army Reserve and roots in the red-leaning Piedmont area, Cunningham had a single term in the legislature on his resume, but he conveniently lacked a lengthy record of votes for Republicans to attack.

Cunningham won the Democratic primary by a clear 57%-35% over state Sen. Erica Smith, though some of the returns suggested that he had work to do for the fall campaign. Specifically, he was relatively weak in areas that had high minority populations — during (and after) the primary, Smith complained that, as a Black woman, she was passed over by the DSCC. But similarly, on the Republican side, Tillis was not beloved by the Trump base, either. The result was a race that the Crystal Ball saw as a Toss-up for much of the 2020 calendar year.

In what was already one of the nation’s most closely watched races, the events of early October rolled in at a breakneck speed. Immediately before the contest’s final debate, on October 1, the Cunningham campaign announced that it had raised over $28 million during the third quarter, shattering the state’s records. The next day, a Friday after both candidates largely stuck to the script in the previous night’s debate, Tillis announced that he tested positive for COVD-19 — this prompted concerns that he had exposed Cunningham, and others, at the in-person debate. But perhaps nothing would define the final stretch of the race more than a report that came out that weekend which suggested Cunningham had an affair months earlier.

As a candidate who put his image as a veteran from a small town at the center of his campaign, the news undercut Cunningham’s credibility. Comparisons to former Sen. John Edwards (D-NC), another state politician who made national news for the wrong reasons, were quickly drawn.

Still, Cunningham continued to lead in polls — there were even some signs that he gained ground with certain demographics as the story developed. Though he occasionally ventured out to make in-person campaign stops, the scandal nonetheless put his campaign on the defensive until Election Day. While the state party didn’t abandon their Senate nominee, other local Democrats tried to keep their distance.

On Election Night, as Trump narrowly held North Carolina by just over one percentage point, Tillis kept his seat by a slightly better 49%-47% spread — the same result he won with in 2014. To political observers, Cunningham’s narrow loss, especially when contrasted with his standing in the polls (in the final RealClearPolitics average, he was leading by nearly three points), begged the question: would the result have been different without the scandal?

Tillis’ upset win made sense in the bigger picture

Despite the narrative of Cunningham’s damaged candidacy, the most straightforward answer seems to be that Tillis’ win, though an upset by many measures, simply “fit” with the other results that year.

As the Crystal Ball has emphasized several times since last year’s election, senatorial races are increasingly falling along presidential lines. Between the 2016 and 2020 election cycles only one state, Maine, voted for a presidential nominee of one party and elected a senator of the other party. In the case of Maine, Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME), who has a well-established history in the state and an independent brand, should be viewed as very much an exception. So Biden losing North Carolina put Cunningham in a tough spot regardless.

The Iowa Senate race was another contest where, despite seeming to have the upper hand at some points in the campaign, Democrats ultimately fell short. As Biden lost Iowa by 8.2%, the Democratic nominee, Theresa Greenfield, came up 6.6% short against Sen. Joni Ernst (R-IA). If Cunningham had run that same 1.6% ahead of Biden, he would have defeated Tillis by a few tenths of a percentage point.

But Iowa, with its almost monolithically white population, lacks North Carolina’s rigid racial polarization. In part because of this, Crystal Ball guest columnist Lakshya Jain has noted that North Carolina is a highly inelastic state that is home to few persuadable voters.

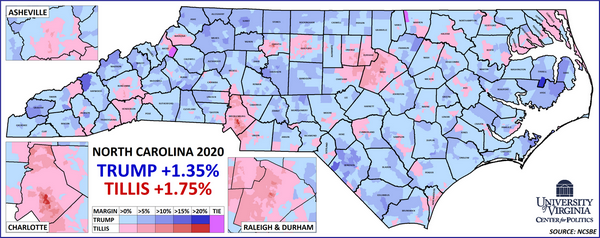

Still, there are some similarities between the two contests. Let’s consider Map 1, which shows the difference between Trump and Tillis in North Carolina:

Map 1: Trump vs Tillis, 2020

Generally, Tillis, in red, outperformed Trump in the state’s urban centers. This difference was especially acute in southern Mecklenburg County and western Wake County — these are essentially the financially better-off, and more transient, communities near Charlotte and Raleigh, respectively. By contrast, Tillis lagged Trump in the rural pockets of the state. The dynamic was identical in Iowa: though Ernst performed worse than Trump in 89 of the state’s 99 counties, the ones where she beat his showing house many of the state’s major cities and universities.

Speaking to Iowa’s greater elasticity, while Ernst ran more than 10% behind Trump in six of Iowa’s counties, Trump and Tillis were within single digits of each other in all of North Carolina’s counties.

In southern states where Democratic senatorial candidates did run ahead of Biden, the margins were not decisive, and the contests themselves were not among the nation’s most competitive. In Virginia, Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) polled two percentage points better than Biden in the Old Dominion to win 56%-44%. Democratic candidates in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina outran the top of the ticket, but did not get nearly enough crossover support to overcome Trump’s double-digit margins in their states.

Georgia, though it narrowly voted for Biden, may be the southern state most comparable to North Carolina. Similar in size, the two are roughly comparable in terms of demographics: each has a sizable Black population (though North Carolina’s is smaller), many loyally Republican rural white voters, and a bloc of college-educated white suburbanites, who are becoming increasingly important in close elections. Though he eventually won in a January runoff, now-Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA), as a challenger, finished two percentage points behind Biden in the November election, and then-Sen. David Perdue (R-GA) did better than Trump in some of the highly-educated suburban areas around Atlanta — similar to the dynamic in North Carolina. So we may have seen Tillis do better than Trump in the suburbs even without the Cunningham scandal.

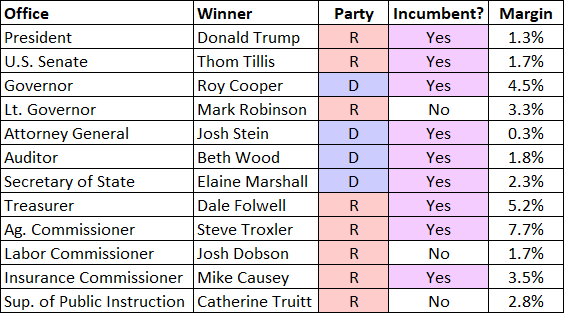

Just within the context of North Carolina’s electoral picture, Tillis’ win also seemed to make sense. Aside from its federal offices, North Carolina elects 10 statewide officers, known collectively as the Council of State. Table 1 shows the results of these races in 2020.

Table 1: 2020 federal and Council of State races in North Carolina

In 2020, no sitting statewide Republicans were defeated. Along those lines, every statewide Democrat who won was an incumbent seeking reelection — and their incumbency wasn’t really enough to guarantee robust margins.

In the case of Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC), his final 4.5% margin was considerably smaller than what polling suggested. Voters reelected Secretary of State Elaine Marshall to a seventh term, but her 2.3% margin was the closest of her career. Attorney General Josh Stein, a likely contender for governor himself in 2024, had razor-close races in both 2016 and 2020. Finally, though Republicans didn’t seriously challenge state Auditor Beth Wood, she still came within two points of losing to a candidate who faced criminal charges.

So a Cunningham win would have really stood out as a pro-Democratic outlier compared to the other statewide results, given that Trump carried the state, no Republican incumbent statewide officeholders lost, and some Democratic statewide incumbents had very close calls without the kinds of problems that Cunningham had.

Third parties, the undervote, and voting methods

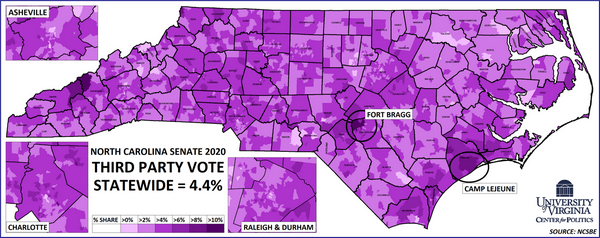

Structurally, one factor that separated the Senate contest from other statewide races was its relatively high third-party vote, though most of the Council of State races only had two-party competition. Excluding write-in votes, third party candidates took 4.4% in the Senate race, compared to only about 1.5% in the presidential contest (excluding write-in votes).

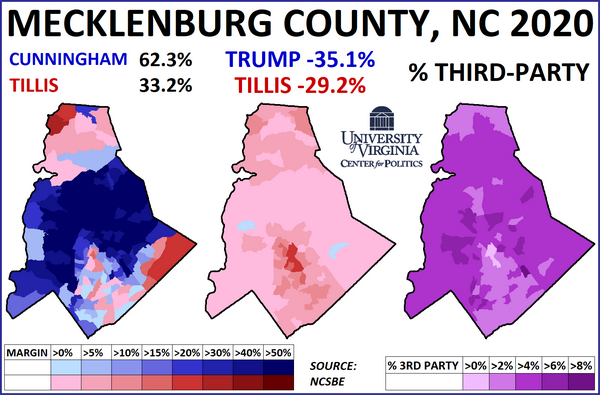

Of the state’s 100 counties, Cunningham ran furthest behind Biden in Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County. Map 2 looks deeper at just Mecklenburg County. The first image shows the Senate margin, the second shows how Tillis’ margin compared to Trump’s, and the last shows the third-party vote. Countywide, its third-party share, 4.5%, about matched the statewide number.

Map 2: Mecklenburg County in 2020

The third-party share was lower in the county’s northern and southern extremes — these are the wealthier, and whiter, parts of Charlotte (earlier in his career, Tillis represented the northern edge of the county in the legislature). If Biden voters were protesting Cunningham’s candidacy, surely this is the area that would see a high third-party vote. Instead, it seems likelier that these voters supported Biden, but preferred Tillis as a “check” on a seemingly imminent Democratic presidential administration — this was a dynamic that helped down-ballot Republicans in 2016 and likely again in 2020 (particularly in a number of House races in similar kinds of places). Given that phenomenon, some Biden/Tillis voters may not have been winnable for Cunningham, scandal or not.

In Mecklenburg County, the third-party vote tended to be higher in precincts that Cunningham carried easily, suggesting he may have lost votes there. But as we’ll see in a later map, some deeply GOP precincts in the state’s western Piedmont also tended to vote third-party at higher rates — likely at the expense of Tillis. This suggests that there was a certain partisan symmetry with third-party voters, and that the Biden/Tillis voters in places like south Charlotte were key to Tillis’ overperformance.

There was also not a particularly large undervote in the suburbs (voters skipping the race on the ballot). This was notable because voters could have also protested by leaving the Senate ballot blank. In fact, the undervote was consistently the highest in Robeson County, specifically in the precincts home to the Lumbee Indian tribe. The area shifted red in 2016 and, somewhat surprisingly, even more so in 2020. As Trump promised the tribe federal recognition if he were reelected, it’s possible that many voters there supported him but left other races blank — so could Tillis, not Cunningham, have been the one shortchanged by the dynamic there?

Still, it does seem that Cunningham’s scandal hurt his chances with some voters. Map 3 shows the statewide third-party share. In the days after Cunningham’s affair came to light, the Army Reserve announced that it was investigating him for potentially violating military rules concerning adultery. The state’s two most prominent military facilities — Fayetteville’s Fort Bragg and Camp Lejeune, in the Jacksonville area — stand out as pockets where third parties did well. Both areas also had relatively high undervote rates. It’s easy to see Cunningham’s conduct turning away veterans and military personnel who would otherwise find his biography attractive.

Map 3: 2020 Third-party vote in North Carolina

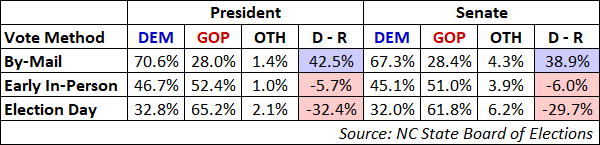

Finally, Table 2 looks at the difference between the presidential and Senate race by voting method. Roughly 65% of the state’s vote was cast early in-person, while the balance was split about evenly between the mail-in and Election Day vote.

Table 2: 2020 vote in North Carolina by method

Perhaps counterintuitively, the only group that Cunningham outpaced Biden with was those who voted on Election Day. Theoretically, these are the voters who would’ve had the most time to hear about the scandal. But Cunningham’s relatively good showing with this group may have had more to do with Tillis’ weakness.

During the campaign season, Trump encouraged his supporters to vote on Election Day. Considering Tillis polled 3.4% lower than Trump with those voters, it’s easy to see some of the former president’s hardcore supporters voting third-party over Tillis, who at times throughout his first term butted heads with Trump. As there was no Green Party candidate (Libertarian and Constitution Party candidates were on the Senate ballot), if there were no third parties in the race at all, Tillis may have been able to do even better, as some of those right-leaning voters may have held their noses for him.

Cunningham’s performance with voters who submitted ballots by mail was especially weak, as his 67% share was more than three percentage points lower than Biden’s. But these voters tend to be disproportionately found in the state’s more affluent precincts — in other words, it’s likely that a high number of these voters would have normally favored Biden and Tillis, anyway. And, as Democrats assured themselves as Cunningham’s scandal was breaking in early October, a fair chunk of this vote had already been cast before the revelations of Cunningham’s affair became widespread (the state began sending out ballots in the mail a month earlier).

Conclusion

As much as we’d like to treat elections like a science experiment — something that can be replicated but tweaked with different variables — they don’t actually work that way. So it’s hard to know with certainty what might have happened had Cunningham’s affair not become public. There is also some indication that it may have hurt Cunningham on the margins, at least in military-heavy areas and quite possibly elsewhere.

That said, we think there are some good reasons to think Cunningham would have lost anyway. Using Occam’s Razor, his biggest problem was that Biden simply didn’t carry the state. Tillis also did better than Trump in the suburbs, something we saw from several other Senate and House Republican candidates across the country in 2020. And Cunningham doing a little bit better than Biden in the Election Day vote — these are the voters who would’ve had the most time to digest the scandal — also suggests that the scandal may not have been decisive.