| Dear Readers: We will be reacting to Wednesday night’s second Republican presidential primary debate on the “Politics is Everything” podcast. Look for it later today here or wherever you get your podcasts.

— The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Like so many other female politicians, Nikki Haley faces a “woman problem” and must combat sexist rhetoric that is prevalent in politics and has been since Victoria C. Woodhull became the first woman to run for president in 1872.

— Campaigns and elections are more challenging for women than men due to structural disadvantages, including media coverage of candidates, public opinion, and stereotypes.

— Women are more pessimistic than men about the prospects for a female president. Fewer women than men think many Americans are ready to elect a woman to higher office even though more women than men personally hope that a woman will become president in their lifetime.

The challenges for women running for president

Like so many other female politicians, Nikki Haley faces a “woman problem.” Despite Haley’s political experience as governor of South Carolina and Ambassador to the United Nations during the Trump Administration, she was not taken seriously as a candidate until the first Republican presidential debate. Coverage only after the first debate conceded that the debate had earned her a second look and made her “harder to ignore” among the contenders.

There is a long-standing precedent for how American female political candidates are treated by the media and viewed by the broader public. Victoria C. Woodhull, our nation’s first woman candidate for president in 1872 as a member of the Equal Rights Party, ran on her support of women’s suffrage, free love, and establishing a new constitution. Her campaign came on the heels of years of women’s suffrage efforts, including an 1871 petition of Congress to allow women the right to vote. Though it should be noted that her feminism, along with others at the time, was racially charged and defined and justified by eugenics.

Figure 1: Women Presidential Candidates 1872-2020

Scroll over to see party affiliation and the total number of votes cast for each candidate.

Newspaper testimonials at the time indicate that the public was not particularly receptive to her campaign, and they took equal issue with her politics as with her womanhood. In November 1871, the New York Times published a profile of a Catholic clergyman who was rapidly gaining popularity by denouncing Woodhull and her policies. At the altar, the clergyman condemned her stance on free love as “highly dangerous to virtue and morality” and closed his address by “warning his congregation against all doctrines so dangerous as those of Victoria Woodhull.” An infamous Thomas Nast cartoon labeled her as “Mrs. Satan.” In a 1927 interview, Woodhull herself recalled, “My sister, Tennessee, and I were mercilessly slandered fifty years ago when we dared to advocate women’s emancipation.”

Flash forward one hundred years: Shirley Chisholm — who won election to the U.S. House from New York in 1968 — became the first Black woman to run for president. Chisholm similarly had to contend with rampant misogyny. She arrived at the Democratic National Convention with a small number of delegates, but her journey ended there. Chisholm was accused of playing “vaginal politics” to “piggyback off of the success of the women’s rights movement.” Journalists were often more focused on reporting on Chisholm’s physical attributes than her policies, a phenomenon that still plagues female candidates today. A 1972 article in the Oakland Post reported that she appeared “diminutive and short in knee-high lace up boots” before making commentary on her campaign promises.

While it would be tempting to dismiss these accounts as historical artifacts, more than a century and half has passed since Woodhull’s candidacy, and we have yet to see a woman ascend to our country’s highest office. What will it take?

Why campaigns are unduly hard for women

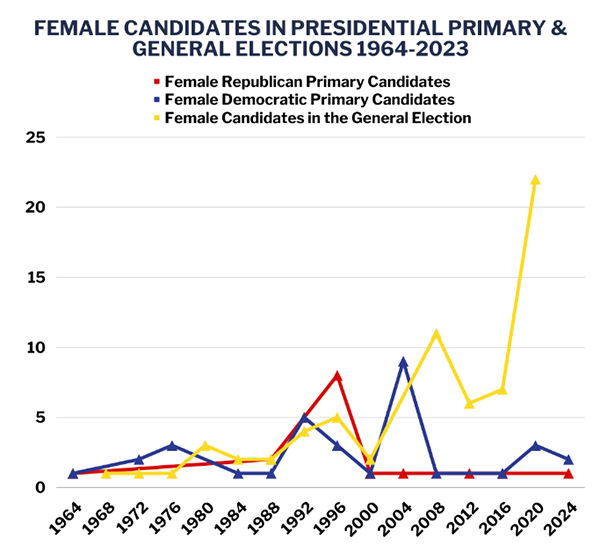

Optimists will say that things are looking up for women politicians. More women are running for higher office (see Figure 2). We have a female vice president, and there are more women in Congress now than ever before. These are some major strides. Or are they?

Figure 2: Female primary and general presidential candidates, 1964-2023

Source: Federal Election Commission; research by authors

There are three main interrelated (though certainly not the only) reasons campaigns and elections are more challenging for women than men: 1) structural disadvantages; 2) media coverage of candidates; and 3) public opinion and stereotypes that impact how voters evaluate candidates. We discuss each reason in turn.

Structural disadvantages

While significant progress has been made by political parties and groups to recruit and train women for office, more work needs to be done. According to a recent study by Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox, men are two-thirds more likely than women to have been encouraged to run by an elected official, party leader, or political activist to run for office. And being asked to run and having the support to run are more important to women than men.

While female candidates running for Congress on average outraised male candidates for the first time in 2018 ($1,675,000 versus $1,537,000), women have historically been disadvantaged when it comes to fundraising. Women have struggled to access and reach large individual donors, PACs, and other kinds of funding.

Another reason why it has been difficult for women to break barriers, especially at the highest levels of elected office, are incumbency and retention rates. Traditionally, men have dominated the political arena, and therefore enjoy the incumbency advantage. When incumbents run and win office, it makes it harder for new voices and interests to enter the political arena. It’s only been in the last 50 years that women have run for office in growing numbers. Women also have similar challenges in breaking into and advancing in the political consulting industry, which Politico Magazine described in a 2018 headline as “the hardest glass ceiling in politics.”

Blame the media

Women candidates continue to face routine obstacles in how they are covered by the media, which also takes the form of gendered and even racialized media coverage on their paths to the White House. When Vice President Kamala Harris was announced as Joe Biden’s running mate in 2020, 61% of the media mentioned her gender and race, while just 5% of coverage mentioned Tim Kaine or Mike Pence’s gender and race in 2016. Research has shown that reporters emphasize women’s traditional roles and focus more on their appearance. Media coverage of women candidates has also perpetuated stereotypes of women politicians as weak, indecisive, and emotional. An analysis of coverage of women presidential candidates in 2020 showed that the media largely characterized women candidates as “nasty, punitive, mean, or strident.”

Not only do women have to contend with obstacles in media coverage, numerous studies have shown that women and other historically minoritized candidates and politicians are significantly more likely to face abuse, harassment, and attacks online than their male counterparts. Women candidates of color are twice as likely as other candidates to be targeted with or the subject of misinformation and disinformation and the most likely to be the target of sexist, racist, and violent abuse online.

Surveys say

With social desirability bias, it is difficult to find voters who admit they don’t think a woman can be president. However, when we dig into public opinion, we can see the challenges women continue to face.

On balance, Democrats are more likely to support women candidates than Republicans. When Hillary Clinton was the Democratic nominee for president, a majority of respondents in multiple surveys leading up to the 2016 election reported support for a woman president or hoped for one in their lifetime (Pew Research, CBS, Harvard IOP, CNN, AP-NORC, and Gallup provide a few examples). On the other hand, more than two-thirds of Donald Trump supporters in 2016 said society as a whole has become “too soft and feminine.” We saw the ways in which masculinity was used as a political strategy in the 2016 Republican nomination process. And, those partisan attitudes persist, including in the electorate. Take for example Rep. Lauren Boebert (R, CO-3), who said she believes “women are the lesser vessel, and we need masculinity in our lives to balance that.”

Furthermore, some surveys following the 2016 elections showed that voters became more cynical about women’s chances in the presidential arena, and especially against Donald Trump (though it’s worth noting here that Clinton won the popular vote in 2016). When asked for major reasons why women are underrepresented in high political offices, more women respondents in 2018 (57%) thought it was because the public was not ready to elect women, a higher number than 2014 (41%). In a different survey conducted in 2019 asking Democrats and independents about the attributes they thought were important in choosing a Democratic nominee that election cycle, those respondents said they were comfortable with a woman being president, but believed their neighbors were less accepting.

Women also face a catch-22 and have to work harder when it comes to how voters evaluate them. Women have to appear qualified and likable, competent and warm. Male candidates simply do not face the same (double) standards that women do in being required to balance stereotypical masculine and stereotypical feminine traits. Republican women candidates in particular receive evaluations that are more critical. And it gets harder as we move the elected political ladder such that women face the biggest challenges at the level of the presidential ticket.

Fair ladies

Are there ways to make electoral politics more fair for the ladies? We’re not holding our breath, but we’ll start with a few ideas. First, research has shown that the visible gender of a candidate alone is not enough to activate a voter’s reliance on gender stereotypes. Voters rely on additional cues associated with gender stereotypes in descriptions or images of the candidate made by other candidates, political groups, and the media, etc. Female candidates have generally responded to gendered stereotypes by being strategic in emphasizing masculine or feminine traits on the campaign trail. However, there’s an important role for a range of actors, especially journalists, political consultants, candidates, and issues groups, to consider how they evoke stereotypes in reporting, messaging, ads, etc. and to do better in how they portray women candidates. It’s going to take more than the Barbie movie to fix how women are portrayed, but to quote Sharon Rooney’s Lawyer Barbie, “I have no difficulty holding both logic and emotion at the same time, and it does not diminish my powers. It expands them.”

Second, the most recent data shows pessimism among women about the prospects for a female president. Fewer women than men think many Americans are ready to elect a woman to higher office even though more women than men personally hope that a woman will become president in their lifetime. Furthermore, greater shares of men than women say it is either “not at all important” or “not too important” or that “the president’s gender doesn’t matter.” As Figure 3 shows, women are more likely than men to say that women still experience a “great deal” or “a lot” of discrimination today in the United States, with the widest gaps in responses between male Republicans and female Democrats. Women also are more likely to see structural barriers facing women in politics, such as lack of support from party leaders, gender discrimination, and having to do more to prove themselves. So we need to do more to bring men along in terms of both understanding the barriers women face and asking for their contributions to help break those barriers down. But, discrimination against powerful female politicians and candidates also transcends race and gender; look no further than Nikki Haley’s adaptation of attacking Vice President Kamala Harris to garner attention for her own presidential bid. Haley’s attacks, in turn, paved the way for other GOP contenders to follow suit.

Figure 3: Views of discrimination against women by partisan identification and gender

Hover over to see details and toggle between different identities.

Source: American National Election Survey.

Finally, numerous surveys have shown that the majority of Americans favor term limits (e.g. Program for Public Consultation at UMD, Ipsos). For offices below the presidential level — where limits already exist for some offices, although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could not impose them on U.S. representatives and senators — term limits could foster greater representational parity. Although term limits are not designed to promote the election of women and other historically marginalized candidates, they could have a positive side effect of increasing opportunities for women to run and win office.

| Kylie Holzman is a second-year UVA student interning with the Center for Politics in Fall 2023. Carah Ong Whaley, PhD, is the Academic Program Officer at the Center for Politics, researching and writing about political learning and participation. She also teaches courses in politics at UVA and is Co-Chair of the American Political Science Association’s Civic Engagement section. |