| Dear Readers: Tomorrow (Friday, Sept. 23) from noon to 1:30 p.m., the Center for Politics will honor the service of U.S. Capitol Police Officers and D.C. Metropolitan Police Officers who defended the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 with the presentation of the Center’s first annual “Defender of Democracy” awards.

This year’s inaugural award recipients will be Private First Class Harry A. Dunn, Officer Caroline Edwards, Officer Michael Fanone, Sergeant Aquilino Gonell, Private First Class Eugene Goodman, Officer Daniel Hodges, Private First Class Howard Liebengood (posthumously), Officer Jeffrey Smith (posthumously) and Private First Class Brian Sicknick (posthumously). An awards ceremony will take place in the Rotunda Dome Room at 12 p.m. on Friday, Sept. 23. Following the ceremony, the officers and widows of the fallen officers will participate in a special panel discussion about the events of Jan. 6, 2021. Doors open at 11:45 a.m. The event is free and open to the public with advanced registration (limited seating remains). The event will also be livestreamed here. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Indications in recent months have pointed to a somewhat mixed midterm result, as opposed to an out-and-out Republican wave, which appeared likelier several months ago than it does now.

— While some factors of 2022 are unique, and while every midterm is different in its own way, the elections of 1978 and 1982 might provide a few clues about 2022.

— Beyond the circumstances of those elections, the opposition party did not realize big Senate gains in either of those years in part because of the makeup of the seats on the ballot — which is also a factor in 2022.

Lessons from 1978 and 1982

“As the nation enters the political year… an unmistakable mood of depression and uncertainty lies across the land. Though the country continues to enjoy a broad-based prosperity and finds itself fighting no wars anywhere in the world, an overwhelming number of us have very little confidence in our political system and the government it provides.”

One could probably have written what we’ve quoted above about the political year of 2022. But the quote itself is from the introduction of the 1980 edition of the Almanac of American Politics, written by Michael Barone, Grant Ujifusa, and Douglas Matthews.

We have been thinking back on past election history in an effort to try to find an election or two that might inform us on what’s been going on this year. Based on our most recent analysis in the Crystal Ball, our best guess of net change in November is a GOP House gain somewhere in the teens and fairly modest net change in the Senate (perhaps no change at all, which would leave the Democrats with the same tied “majority” they have now, courtesy of Vice President Kamala Harris’s tiebreaking vote).

If this is roughly what happens 7 weeks from now, it might seem like an odd outcome for a president, Joe Biden, whose approval rating is still clearly underwater despite a recent uptick. That’s because poor presidential approval contributing to significant presidential party losses in the House and/or the Senate have been a feature of the last 4 midterms (2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018). But there have been some indicators that 2022 may be different than those years, so maybe the more distant past offers some parallels.

Expecting any past midterm to perfectly foreshadow this one would be foolhardy. History can provide a rough guide about what we might expect under certain conditions, but it can also serve to limit one’s imagination if something truly unprecedented happens. A case in point would be one Donald J. Trump capturing the GOP presidential nomination in 2016, especially given the then in-vogue belief that candidates like him couldn’t win nominations without much formal support from elites in the party (it turns out a candidate like him could).

We also don’t think there’s much obvious, recent historical precedent for the Supreme Court’s landmark abortion decision back in June, at least in terms of it as a midterm factor. The Dobbs decision is one of the most important in recent decades, and it’s also unpopular. It’s also rare for the party that does not control the presidency or Congress to enact what is effectively a profound change in national policy, but that’s what the court, controlled by Republican appointees, has done. Typically, the party making changes is the one in control of the elected branches, and the midterm can serve as a backlash to those changes. The Dobbs decision complicates that usual dynamic.

But ignoring history completely is also unwise; otherwise, one may fall into the trap of arguing that something is “unprecedented” when, in fact, it is not without precedent. Certainly a sour electorate is nothing new — as the quote above from 4 decades ago illustrates. Nor is there anything unique about the opposition party coming up short in certain ways in a midterm — if that is indeed what happens this year.

That said, the specifics of this election, featuring both an unpopular president and also indications that the unpopular president’s party won’t be strongly punished, are a bit unusual.

It is pretty easy to find post-World War II midterms where unpopular presidents preside over bad midterm outcomes; in addition to the last 4, years like 1946, 1966, and 1994 all qualify. One can also find instances of presidents with decent approval ratings presiding over bad midterms for their party, like 1958 and 1974 (the latter was Gerald Ford’s lone midterm, and the legacy of Richard Nixon and Watergate was likely a bigger factor than Ford’s approval rating). Popular presidents also can preside over good midterms for their party, like 1998 and 2002 — the only 2 instances since the war when the president’s party netted House seats in a midterm — but also years like 1962 and 1990, when the president’s party lost a little ground in the House but otherwise did well.

There are a couple of years, though, that might provide some clues for the 2022 situation. They also are midterms that don’t generally come up in lists of memorable U.S. elections — thus, readers may not remember them well or know their particulars: 1978 and 1982.

For various reasons, one could argue that both of these elections could or should have been worse for the president’s party than they otherwise were.

In 1978, Jimmy Carter’s lone midterm, Republicans only made a small numerical dent in the Democrats’ House and Senate majorities — they netted 15 seats in the House and 3 in the Senate, allowing Democrats to retain both chambers.

Carter would lose to Ronald Reagan in 1980. Republicans flipped the Senate that year, but not the House despite making a net gain of nearly 3 dozen seats.

The Reagan Revolution gave the GOP dreams of flipping the House for the first time in 3 decades; in 1981, the Republican National Committee chairman, Richard Richards, “flatly promised a House takeover.” But instead of Republicans netting the 26 seats they needed to win the House, they ended up losing 26 seats as Reagan struggled with low popularity and economic problems. However, while the House change in 1982 reflected a good Democratic environment, it was pumped up by Democratic redistricting gains that year. And Republicans held serve in the Senate.

Let’s take a closer look at these elections, and see what we might glean from them.

One commonality between these 2 elections and the election we’re having now is the issue of inflation. Rising prices was a common problem for Americans in the 1970s through the early 1980s, when then-Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker — a Carter appointee who had also served in an important role at the Treasury Department under Richard Nixon — stamped out inflation through high interest rates. Many of the inflation statistics reported in recent months are the worst in 4 decades — right around the time of these 2 midterms.

Carter, though generally unpopular throughout his tenure, saw his approval rating improve to 49% in the final Gallup poll before the midterm. This was after he had been mired in the low-40s from about mid-April to mid-September. One contributor may have been the Camp David Accords, the Sept. 17, 1978 peace agreement between Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin that Carter helped broker. Regardless, the timing of Carter’s improved approval may have helped limit Democrats’ losses that year. We see something similar this year with Biden, although his approval improvement has still only put him in the low 40s in approval averages (he was in the 30s a couple of months ago).

Perhaps more impactful to the results in 1978 was the campaign that was actually run, in which observers at the time and also in hindsight felt that Democrats outflanked Republican messaging on economic and government spending issues. Republicans ran that year on a tax cut proposal from then-Rep. Jack Kemp (R-NY) and then-Sen. William Roth (R-DE). But Democrats responded by arguing that the tax cuts would be inflationary (in a time when inflation was a major issue). They pushed instead for spending cuts, “co-opting normal Republican rhetoric,” Congressional Quarterly’s summary of that election year noted. It may have been easier for Democrats to get away with that back in the 1970s, when the ideological makeup of the Democratic congressional majorities was much more mixed than it is today.

“House Republican candidates blew it,” wrote William Safire, a former Nixon aide who at the time was on the front end of what would be a long stint as a New York Times opinion columnist. In the opening paragraph of his post-election column, headlined “Dishing the Whigs,” Safire used a long-ago quip from British politics as a way of arguing that Democrats had stolen Republican messaging: “‘Don’t you see we have dished the Whigs?’ That was the delighted observation of England’s Lord Derby a century ago, when his conservatives stole the opposition platform and rode the Whig reforms to a Tory victory.”

Democrats have yet to, in our eyes, find an effective answer to Republicans’ messaging in this election on inflation, although it is possible that the drop in gas prices has taken a bit of the air out of the inflation issue more broadly. Democrats may also be able to basically change the subject in their own way, through the abortion issue. It is an interesting side note to 1978 that some observers, like the authors of the Almanac of American Politics, saw the rise of “single-issue” politics in some races. Abortion was one: Republican Roger Jepsen defeated Sen. Dick Clark (D-IA) in part by hurting Clark’s margins with traditionally Democratic Catholics by focusing on the incumbent’s record of supporting the right of federal benefit recipients to use those benefits for abortions.

Jepsen was “generally considered a lightweight,” according to the Almanac authors, but he beat the Democratic incumbent anyway. As we and others have noted, the GOP is trying to beat Democratic incumbents this year with what appears to be a lackluster stable of candidates. But candidates regarded as weak sometimes win, particularly if they can find salient issues over which they can attack an incumbent.

As it was, 1978 is also remembered as a year in which the Democrats’ relatively mild losses obscured what was actually going on in American politics — a turn to the right that was much more fully realized when Reagan beat Carter and Republicans flipped the Senate in 1980.

In Reagan’s first midterm, inflation, as well as Volcker’s recession-inducing interest rate spikes designed to combat it, contributed to a sour economic environment. Reagan’s approval rating had sunk to the low 40s in Gallup’s polling by July, and it stayed there through the election. Yet the results were not all bad for Republicans.

Democrats picked up 26 House seats, but Crystal Ball Senior Columnist Alan Abramowitz found that redistricting was a major factor in these gains. Roughly half of the Democratic gains came in the 17 states where Democrats had complete control of redistricting. This was not a repudiation along the lines of what Republicans had endured during the most recent midterm held during their control of the presidency: In both 1972 and 1980, Republican presidential victories, Republicans won 192 House seats. In 1974, their total was reduced to just a paltry 144. But in 1982, they held onto 166 seats — still a small number, but representative of a higher floor for the party than in the 1970s (since 1982, the Republicans have never dipped below that number of seats). So part of what may have been going on is that the Republicans, for so long a minority in the House — they would only win House majorities 2 times in the 6 decades between the early 1930s and early 1990s — were starting to come out of the wilderness a little bit. For the purposes of 2022, remember that Republicans already won 213 House seats in 2020, which was always going to limit their ability to score a huge numerical gain this year, just because they are starting from such a high floor.

Andrew Busch, author of a history of midterm elections (Horses in Midstream), argued that Democrats did not do quite as well as they could have in 1982 in part because Republicans were able to pin some of the blame for economic problems on Democrats, and that despite the economic pain, the inflation problem was getting better. Busch as well as House scholars Gary Jacobson and Jamie Carson also pointed to superior Republican resources in 1982 as a factor; this year, Democratic candidates in close races generally enjoy a resource advantage, although outside spending can even things out to a large degree.

In the short term, though, 1982 was impactful for governance. In 1981 and 1982, the alliance between Republicans and the still-numerous House Democratic conservatives gave Reagan a working majority for some of his agenda. The enlarged Democratic majority gave liberals more power in the House and made life harder on Reagan’s agenda.

As noted above, Republicans protected their Senate majority in 1982. This came very close to being a far different outcome; Barone and Ujifusa, in the Almanac of American Politics 1984, wrote that a switch of a few points of the vote in each of 5 states would have given Democrats the majority that year. Democrats would eventually win the Senate back in Reagan’s second midterm, 1986, on the strength of some razor-thin results of their own. Given how close the polling is in many of the key Senate races this year, and the fact that nearly all of the closest presidential states in 2020 have Senate contests this November, it wouldn’t take much to tip the election one way or the other.

Beyond the unique circumstances of 1978 and 1982, an explanation for the Senate results mirrors a factor that we see this year: The seats up in those years just weren’t that favorable for the non-presidential party.

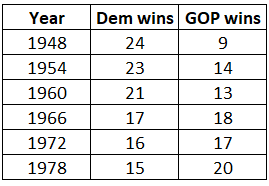

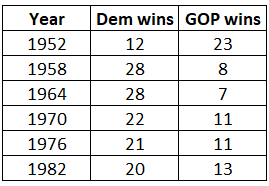

Tables 1 and 2 show the Senate results in, respectively, 1978 and 1982, as well as in the 5 previous elections those Senate classes were on the ballot. The total number of seats contested from year to year varies because some years include special elections and also because seats sometimes changed hands in the years between the regular elections for these seats held every 6 years. We also did not include independents in the party tallies. The tables themselves are based on data compiled by FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley, who put together a voluminous trove of historical Senate research while he worked with us at the Crystal Ball.

Table 1: Class 2 Senate results, 1948-1978

Source: Crystal Ball research

Table 2: Class 1 Senate results, 1952-1982

Source: Crystal Ball research

On Table 1, note that Republicans had already been chipping away at the Democratic edge in Class 2, with a breakthrough coming in 1966, a GOP wave year against President Lyndon Johnson. By the 1978 election, the parties were at rough parity on Class 2, which gave the Republicans fewer opportunities for gains (Safire, in the 1978 column, lauds Senate Republicans for picking up seats despite the party’s “numerical vulnerability” that year).

Meanwhile, in Class 1 — contested in 1982 — Democrats had not had a poor election since 1952, when Republicans flipped the Senate in the midst of Dwight Eisenhower’s presidential victory (Republicans had also flipped the Senate amidst big gains in 1946, the last time that Senate class had been on the ballot before 1952). But Democrats enjoyed a couple of the best elections in the party’s history in the 1958 wave, when economic problems and other issues crushed the Republicans despite Ike’s enduring strong approval rating, and then in 1964, when Johnson won his landslide victory. The huge size of the Democratic Class 1 edge contributed to modest GOP Senate gains in 1970, Nixon’s first midterm, and featured an election with hardly any net change in 1976. So by 1982, Democrats already had a big edge on this Senate map, giving them limited avenues to capitalize on Reagan’s problems. Republicans would not enjoy a wave on this map until 1994, the epochal year where Republicans won both the House and Senate for the first time since the 1952 election, and Democrats would then enjoy some strong results on this Senate map in subsequent elections. This is the same map that was contested in 2018; Democrats defended 26 of 35 seats on the ballot that year, and ended up losing a little ground despite a good political environment. This map will be up again in 2024, and it looms in the background as a potential treasure trove for Republicans, as Democrats will be defending all 3 seats they hold in Trump-won states (Montana, Ohio, and West Virginia) as well as several others in marginal Biden-won states (Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin). Overall, Democrats currently hold 23 seats on the 2024 Senate map (including Maine and Vermont, held by independents who caucus with Democrats), while Republicans hold just 10.

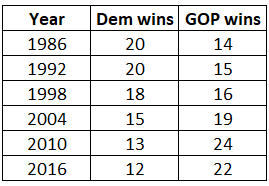

Republicans already enjoy an edge in Class 3, the group of Senate seats being contested this year. Table 3 shows some recent Class 3 results. As is clear from the tables, Republicans have had some solid recent elections on this map — they added to their Senate majority in 2004, took a big bite out of the Democrats’ majority in 2010, and then held the majority they had won in 2014 2 years later in 2016. This year, Republicans are defending 21 of the 35 Senate seats being contested — a simple numerical reality that complicated their path to a Senate majority even before the party nominated shaky candidates in many races and as the political environment became murkier over the past couple of months.

Table 3: Class 3 Senate results, 1986-2016

Source: Crystal Ball research

Conclusion

One important thing to remember is that even if Republicans don’t necessarily enjoy a “wave” this year, it’s not going to take much to flip both chambers. What they did in 1978 — 15 House seats and 3 Senate seats — would be more than enough to win both chambers in 2022.

The thing about electoral history is that national elections don’t actually happen all that often — there is only 1 every 2 years, and only 1 midterm every 4 years. Even if we take the whole history of midterms since the Civil War — which basically covers the entire history of our current party structure, featuring Democrats and Republicans as the 2 major parties — we only get 40 elections. It is true that the presidential party has lost ground in the House in 37 of those 40 elections, although there are huge disparities in actual outcomes, and the overall sample size isn’t that big.

Every midterm has its own set of circumstances, and while the pendulum usually swings against the president’s party, it does not always swing that much — and on occasion it really doesn’t swing at all.

While we have become accustomed to big wave elections, like the last 4, even they come with caveats. Democrats came out of 2018 with slightly fewer Senate seats than they had going in; Republicans made a big Senate gain in 2010 but still kicked away a few races, leading to the reasonable conclusion that they could have done even better.

Many of the midterms prior to 2006 were more mixed, with the presidential party doing well in both 1998 and 2002, and not that poorly in many of the midterms prior to 1994. The midterms described above, 1978 and 1982, are arguably a couple of such examples. Perhaps 2022 will be as well.