| Dear Readers: The Crystal Ball will be away through the end of year. We wish all of you Happy Holidays, and we will be back the first week of January.

Join us on Friday, Jan. 6, 2023 at 6:30 p.m. for an exclusive first look at our upcoming documentary on the events of Jan. 6, 2021 as experienced by officers on the frontline. The event will feature a discussion with several of those officers and will be held at the UVA Rotunda Dome Room. To register to attend, either in-person or virtually, visit Eventbrite. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— As with other states across the South and the nation, Black turnout last month was not as strong as Democrats would have liked.

— This was seen in North Carolina, where Republicans, as has usually been the case for the last few decades, narrowly came out on the winning side of a Senate race.

— Still, last month’s result may send mixed messages for the parties going forward.

— Democrats are strong favorites to win the VA-4 special election and are voting on a nominee today.

North Carolina in recent midterms

While Democrats broadly overperformed expectations in last month’s midterms, some weak spots in their coalition have become evident as more detailed data has emerged. Generally, Democrats relied more on persuasion — convincing swing voters to stick with them, as opposed to going with the other guys — than turnout. In several of the historically Republican suburban counties across the country, this played well for Democrats. But as news organizations like the New York Times have found, the Black vote, a key part of the Democratic coalition, was not especially animated this year.

Because our neighbor to the south, North Carolina, provides extensive post-election turnout data, we wanted to look in detail at how some of those trends played out in the Tar Heel State (and the author, who grew up there, has since kept an eye on its politics). As we noted last week, North Carolina was 1 of only 7 states to be decided by less than 3 points in the 2020 presidential race — and the only state among that group to vote for Donald Trump. While the state has become more competitive for president since the beginning of the 21st century, it has voted Republican for president in 10 of the last 11 elections, with the only exception coming in 2008.

Though its race wasn’t in the highest tier of battleground Senate contests — the Crystal Ball had it rated as Leans Republican the entire cycle — 2022 was another cycle where Democrats came up a few points short in North Carolina. Rep. Ted Budd (R, NC-13) — who was, in retrospect, one of the better Trump-endorsed candidates running in a marginal state — held the state’s open Senate seat for Republicans by just over 3 percentage points. He beat former state Supreme Court Chief Justice Cheri Beasley (D).

Beasley was not a weak candidate: In 2020, as Joe Biden lost North Carolina by almost 75,000 votes, she lost her seat by 400 that year. Part of what made her an attractive candidate to Democrats was that, as a Black woman with statewide stature, she seemed well-positioned to inspire minority turnout. In 2020, Cal Cunningham, a white man who was their Senate nominee, got fewer votes than Biden in most areas of the state that have high Black populations — this was something that, if rectified, could have helped Democrats close the gap.

But as it, ironically, turned out, Beasley beat Cunningham’s numbers in most of the state’s wealthier suburbs while losing ground in minority-heavy rural counties. One of the most salient examples of this dynamic was Anson County, which sits at the eastern edge of the Charlotte metro area. The county is small, with a population of 22,000, but its trends are mirrored in about two dozen other eastern North Carolina counties, and many more throughout the South.

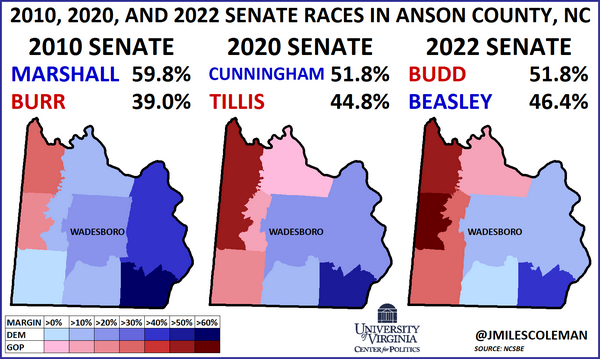

Map 1 gives a bit of historical perspective. Anson County is split about evenly between white and Black residents — the former group is concentrated in the western precincts while the latter are more in the east, and around the county seat of Wadesboro. In 2010, the last time this Senate seat was up in a Democratic midterm, the now-outgoing Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC) was reelected 55%-43% but took less than 40% there. In 2020, Cunningham slightly outran Biden in Anson County, but the Democratic margin dropped to 52%-45%. Even as the Beasley campaign made multiple stops there, Budd carried it with the same 52% as Cunningham.

Map 1: NC Senate elections in Anson County

As surprising as this result was — while the county’s historic allegiance to Democrats was waning, it was notable that it actually flipped — it makes more sense in context. Table 1 goes back to 2010, looking at voter turnout rates by race in North Carolina midterms.

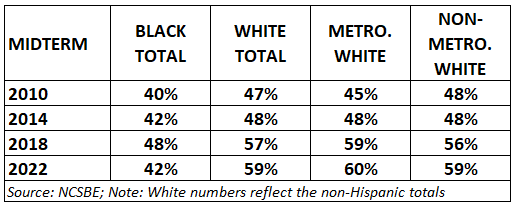

Table 1: Turnout rates in recent North Carolina midterms

In 2022, total non-Hispanic white turnout was similar to 2018, inching slightly upward. But Black turnout in 2022 was more comparable to the red wave years of 2010 or 2014. Perhaps tellingly, Black voters were more enthused in 2018 — the only cycle on Table 1 where North Carolina lacked a Senate race — than they were in 2022. Though the raw vote totals aren’t shown on Table 1, in both 2014 and 2022, almost the exact same number of Black voters cast a ballot (just under 630,000 in each case).

To be fair to Beasley and North Carolina Democrats, low Black turnout was, again, a national problem for Democrats this year. It was especially pronounced in the South, given the region’s large Black population. In Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, and South Carolina, several heavily-Black rural counties that easily went for Barack Obama 10 years ago gave the GOP nominees for governor clear margins last month. In the Georgia Senate race, Sen. Raphael Warnock’s (D-GA) numbers in non-urban Black areas were down from his 2021 showing — but, as Georgia has less of a rural component than North Carolina, Warnock won by expanding his margins in the Atlanta metro area.

While the lower Black turnout clearly hurt Democrats’ prospects this year, the dynamics among white voters did not appear helpful, either. Table 1 divides white voters into “metro” and “non-metro” categories. A little less than half (45%) of the state’s white residents would fall under the “metro” category — they live in the state’s dozen most populated counties, all of which have over 200,000 residents. The “non-metro” whites make up the remaining 55%. Generally speaking, as realignment has taken hold, white voters in the state’s metro areas have trended Democratic while rural whites have moved Republican. In 2018, metropolitan whites voted at a rate 3 percentage points higher than their “non-metro” counterparts. This year, the split was more even, as it was in 2014.

In the years since Obama carried the state in 2008, federal races in the Tar Heel State have been a recurring source of consternation for Democrats — they have gone 0 for 8 in presidential and Senate races since that banner year. While transplants from other states have boosted Democratic margins in many large counties, it has not entirely been a net plus for them. Over the past decade, one of the fastest-growing counties (by percentage, not raw, change) in the state has been coastal Brunswick County. The growth there has been fueled by conservative retirees, giving Tar Heel Democrats something of a “Florida problem.”

All that said, North Carolina Democrats have some reasons for optimism. For one, going forward, while national Democrats won’t put North Carolina in the same “must win” category as several Midwestern states, it may seem like a less daunting “expand the map” target than Florida, especially after this cycle. Second, as Table 1 suggests, the 17 percentage point gap between white and Black turnout rates was easily the largest of any recent midterm. With that in mind, Beasley’s 3-point loss seems more respectable. This may be because Democrats’ suburban gains seem to be taking hold. The south Charlotte precinct where the author grew up gave Mitt Romney a 60%-37% margin in 2012 — in 2020, it favored Biden by 10% and Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) by a point. Beasley carried it by 7% last month.

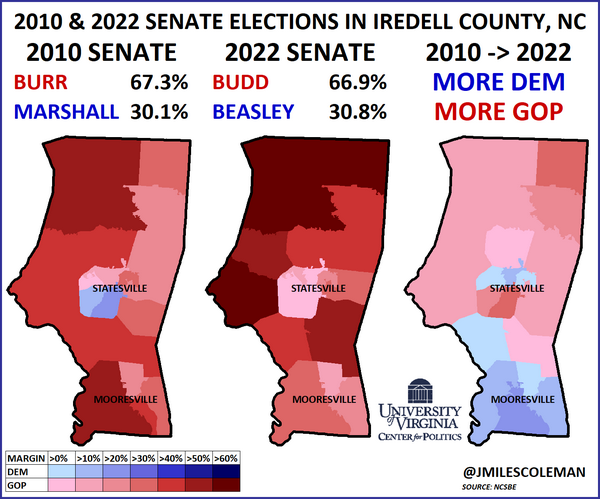

Finally, sticking to the Charlotte metro area, Twitter mapper @UniteCarolina recently posted a statewide precinct map of the Senate contest. One county that caught our attention was Iredell, which sits just north of Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County. Iredell is not a swing county by any means — it gives Republicans commanding majorities — but there are some interesting internal movements there.

In the 2010 and 2022 Senate elections, Iredell County gave the Republican nominees almost identical percentage margins, as Map 2 shows.

Map 2: 2010 and 2022 Senate elections in Iredell County

Despite the overall stasis, Democrats gained in the southern precincts (they correspond to the city of Mooresville), as seen in the swing map. Southwestern Iredell County borders Lake Norman and includes some of the priciest real estate in the county. In other words, these are the types of Republicans who likely prefer a less Trumpian GOP.

When analyzing the voting trends of fast-growing states like North Carolina, it’s important to keep in mind that the electorate is in a constant state of flux.

In the center of the county, Statesville is Iredell’s county seat. In recent elections, even as Democrats would get blown out countywide, they’d still almost always Statesville’s two southern precincts — this was the case in 2010, as Democrat Elaine Marshall carried them. But last month, Budd swept the city. While this was tempting just to chalk up to poor Black turnout, changing demographics seemed to be a factor. In 2010, those two precincts, taken together, were 47% Black by composition. According to DRA 2020, as the city has grown over the last decade, that number is now closer to 40%. That is a not-insignificant drop, and as Statesville becomes more of a bedroom community to Charlotte, its newer residents may not be loyal Democrats.

Meanwhile, the northern precincts in Statesville, which have long been whiter and relatively higher income, are seeing a pro-Democratic trend, similar to that of the Mooresville area. But Republican margins have gone up in the surrounding rural precincts, and, compared to Burr in 2010, Budd netted an additional 9,200 raw votes out of Iredell County.

Essentially, Iredell County was worth examining because it’s exactly the type of county that keeps North Carolina red: while Democrats have made gains, this dense exurban county still retains its fundamentally Republican character. Even with the blue trend in the southern part of the county, for example, Beasley didn’t actually carry any precincts there.

While North Carolina won’t see another Senate race in 2024, it will hold several other down-ballot contests. One of the continuing points of Democratic success in the state has been the governorship — over the past 3 decades, they have held it for all but 4 years. Democrats will be working to retain that office, as popular incumbent Roy Cooper (D) will be term-limited. At the congressional level, the state delegation is now evenly-split, at 7-7, but Republicans are likely to get a boost going into 2024: the GOP-controlled legislature will get to draw a new map, and will now have a friendly state supreme court (we will cover that as it unfolds).

P.S. VA-4 special election is Safe Democratic

Moving slightly back up north to our home state, the unfortunate death of Rep. Donald McEachin (D, VA-4) prompted the first special U.S. House election that the commonwealth has seen in nearly a decade. Though the district includes some Southside localities that are seeing that same types of trends that Anson County is, VA-4 includes the entire city of Richmond, which pushes it into Safe Democratic territory — last month, McEachin was reelected by 30 points.

The special election will take place on Feb. 21, but local Democrats are choosing their nominee today via a “firehouse primary.” A firehouse primary is essentially a party-run primary that features a handful of polling places across the district. Given the lean of VA-4, the winner of the Democratic contest will very likely be its next member of Congress.

McEachin, who had a long career in Virginia politics, was succeeded by fellow Democrat Jennifer McClellan in the state Senate after he was elected to the House in 2016. McClellan is again running to replace McEachin, and has much of the party’s weight behind her. Last week, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA), who lives in the district and formerly served as mayor of Richmond, endorsed her. The Democratic elite rallying around McClellan prompted a leading rival for the seat, state Del. Lamont Bagby (D), to drop out and back her, as well.

The consolidation behind McClellan was part of a larger Democratic effort to sink the candidacy of state Sen. Joe Morrissey (D), who is the least reliable member of state Democrats’ narrow 21-19 majority in the state Senate. Despite a long list of controversies, Morrissey does seem to have a strong local brand, and he ousted an establishment-backed incumbent state senator in a 2019 primary. Morrissey has been written off before, so we wouldn’t totally rule him out in today’s primary. But McClellan is widely seen as the favorite.