| Dear Readers: This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, which features short updates on elections and politics.

— The Editors |

The Trump coalition: A case of beer plus a bottle of wine

Former President Trump does not drink, but his enduring political coalition within the Republican Party is heavy on beer and not lacking for wine.

What we’re referring to is the political phrase “wine track vs. beer track,” a handy construction coined by the shrewd political analyst Ron Brownstein to describe fissures within presidential primary coalitions that we’ve borrowed from time to time in our own analysis. Wine track basically means white collar/college-educated, and beer track indicates blue collar/not college-educated. Trump has been stronger with the beer track than the wine track.

In March, we wrote that one of the keys for any Trump alternative was to “consolidate the ‘wine track’ (college-educated) vote at least as well as Trump consolidates the ‘beer track’ (non-college) vote.” No one is coming even close to doing that at the moment — and there are signs that Trump is improving among the college-educated Republican vote.

Back in late February, the GOP firm Echelon Insights showed Trump leading nationally among Republicans with 46% and Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) second at 31% (all of the polls referenced in this piece included other candidates than just Trump and DeSantis, although of course the roster of contenders has changed over the course of the year). In that poll, Trump was up 54%-27% on DeSantis with non-college voters, but DeSantis had a nominal lead on Trump, 36%-33%, among college-educated voters.

In the firm’s late June survey, Trump’s share of the vote was very similar to the February poll, but his overall margin over DeSantis was much larger: 49%-16%. Trump was up 54%-15% with the non-college bloc, but also up 41%-17% among the college bloc. So Trump’s non-college share was the same but his college share had grown. Take these numbers among subgroups with more than a grain of salt, because they can be statistically noisy, but Echelon is not the only poll to show this.

Back in mid-March, Quinnipiac University’s polling had essentially the same topline GOP finding as the earlier Echelon survey: Trump was leading DeSantis 46%-32%. Among white Republicans without a four-year degree, Trump was up 48%-31%, but DeSantis was up 40%-28% among the white college group. Another Quinnipiac poll from earlier this month had Trump up 54%-25% on DeSantis: Trump was leading 60%-24% among non-college whites and also held a nominal lead with college whites, 34%-29%. (This poll, unlike the others cited here, included education level just among white Republicans as opposed to all Republicans, but GOP primary electorates are very white in most places, so we think it’s OK to compare this Quinnipiac poll against the others.)

Other recent polls have shown Trump in a solid position with college-educated Republicans. Over the weekend, Fox Business polls of Iowa and South Carolina showed Trump near 50% in overall support in both key, early states, with none of his rivals reaching even 20% in either state. Trump was at 57% with the non-college group in Iowa and 53% in South Carolina, but he was also leading with college-educated voters in each state, too, at 33% and 41%, respectively.

The basic story is the same in all of these polls: Trump has maintained a strong lead with beer track Republicans and is also doing better than he needs to do with wine track Republicans, leading with this group in these surveys. Meanwhile, DeSantis has been struggling: In our March assessment, we wrote that we needed to see DeSantis as an actual national candidate before determining how much of a threat he posed to Trump. His performance so far has been wanting, as his numbers are generally weaker now than they were months ago and his campaign is already in the midst of a cost-cutting reboot just two months after his official entry into the race.

There are of course lots of interesting subplots in the GOP campaign — the struggles of DeSantis, some hopeful signs for Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) and outsider entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy, etc. One can find some weak spots for Trump, like his serious legal travails and a recent Pew poll that found that a third of Republicans hold an unfavorable view of him. But that’s of course a far cry from a majority, and it’ll take at least a majority of Republicans — and probably much more than that, given the splintered field — actually voting against Trump in order for him to lose the nomination.

So as the calendar turns to August, Republicans on both the beer track and, to a lesser but still significant extent, the wine track remain supportive of the former president, with the other candidates trying to claw away from DeSantis a distant second.

Republicans’ Alabama redo map heads to court

While several states are on our radar for post-2022 redistricting this year, the situation in Alabama has made the most recent and significant national news. Last month in its Allen v. Milligan decision, the Supreme Court threw out the state’s congressional map. The now-defunct map only contained a single Black-majority district, the heavily Democratic AL-7 that has had its basic configuration since 1992. In issuing its opinion, the high court essentially agreed with a lower ruling from a three-judge federal court that ordered the seven-seat map be redrawn to include a second such Black-majority district, or “something quite close to it.”

Earlier this week, Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed off on a remedial map that her GOP-led legislature passed during a special session. Ivey’s signature came despite the fact that legislative Republicans did not come especially close to creating a second Black-majority seat. GOP mappers somewhat unpacked District 7 while upping the Black population in District 2, which includes Montgomery and the southeastern corner of the state, from about 30% to 40%.

Given the electoral realities of Alabama’s racially polarized voting, we are skeptical that the redrawn 2nd District would elect a candidate preferred by its bloc of Black voters. While now-former Sen. Doug Jones (D) would have carried the newly-enacted AL-2 by a dozen points in his 2017 victory — an unusual result driven by the horrendous quality of his opposition — Jones would have lost the district by 4 points when he was up for reelection in 2020. No other recent statewide Democrat has carried anything other than the 7th District, as was the case with the outgoing map.

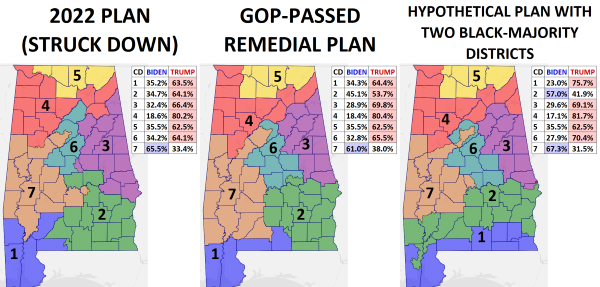

With that, Map 1 considers several Alabama plans.

Map 1: Alabama redistricting maps

Source: DRA 2020, with election data from VEST Team; shapefile for the remedial plan was provided by Drew Savicki

The first image shows the outgoing plan. The second image shows the newly-enacted map — as with the old plan, it features just a sole Biden-won district. The third image is a hypothetical configuration that features two Black-majority, Biden-won seats. District 7 includes much of Birmingham’s Jefferson County and is 57% Black by composition, while the 2nd District becomes a 53% Black seat that follows Interstate 65 from Mobile to Montgomery.

When the Supreme Court threw out the old map, we moved one of Alabama’s districts from Safe Republican to Likely Democratic, and that change still stands. The Republican-passed map will now go before the same three-judge panel that tossed the old map. It’s possible, if not likely, that the judges will reject the GOP’s remedial map and draw their own replacement map — we’d expect such a plan to look something like the third image on Map 1.

The third map would likely induce a primary between Reps. Jerry Carl (R, AL-1) and Barry Moore (R, AL-2). At least geographically, Carl would be favored, although either could opt to just retire. By passing a map that didn’t comply with the spirit — or, really, the letter — of the court’s ruling, legislative Republicans may have wanted to give the three-judge panel the task of choosing which GOP member to throw under the bus as opposed to having to do it themselves.

The hypothetical Mobile-to-Montgomery seat would favor Democrats, but notice that it would not be as cast iron as the 7th District — the new 2nd gave Biden 57%, a share 10 points lower than what he would have taken in the new version of the 7th. That difference also factored into our thinking when we called a potential new Black-majority seat Likely Democratic instead of Safe Democratic.

Aside from the images shown in Map 1, it’s possible, though probably less likely, that the three-judge panel may go with something similar to what a Democratic legislator floated during last week’s special session. Jefferson County, which typically votes for Democrats in statewide elections, has about the ideal population for a congressional district. Though the county’s population is only about 41% Black, its urban whites are considerably more Democratic than those in the rural parts of the state. So, in contrast to the 40% Black 2nd District that Republicans drew last week, a Jefferson County-based district could likely perform as a Black-majority seat would. In this scenario, a Tuscaloosa-to-Montgomery seat would also be amenable to a Black candidate.

The Milligan decision was certainly seen as a victory for Democrats, and voting rights advocates, and it could well have repercussions in other states. But, aside from changing the rating of a single district in Alabama, we tried to avoid rushing to any sweeping conclusions about the ruling’s scope for the 2024 cycle. The reluctance that Alabama Republicans are showing — the state seems likely to get a second heavily Black seat for next year, but they are making the process as cumbersome as possible — seems to be vindicating our “wait and see” approach.