KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Currently, one party controls all of the statewide elected executive offices in 36 of the 50 states.

— Candidate decisions by down-ballot executive officeholders in Florida and Missouri could make Republican statewide sweeps easier in those states, and Democrats may have opportunities to sweep more states on their side.

Party control of statewide offices

Three of June’s most significant candidate announcements involved Democrats who serve in elected, down-ballot statewide offices. Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs (D) and Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Nikki Fried (D) launched bids for governor. Meanwhile, Missouri state Auditor Nicole Galloway (D) announced that she would not seek a second, elected full term in her position.

Depending on how things go in their respective states next year, their decisions could have an impact on the dwindling number of states that have members of both parties serving in statewide elected offices.

While it’s natural to just focus on state governorships and legislatures when assessing politics in the states, nearly all of the states — 44 of 50 — have partisan, statewide elected executive offices beyond the governorship. These range from higher-profile positions like attorney general and secretary of state to more obscure offices like land or agriculture commissioner. These positions often set up their occupants to run for governor or senator; indeed, the roster of announced or potential candidates for those top-tier jobs this cycle is dotted with these kinds of officeholders.

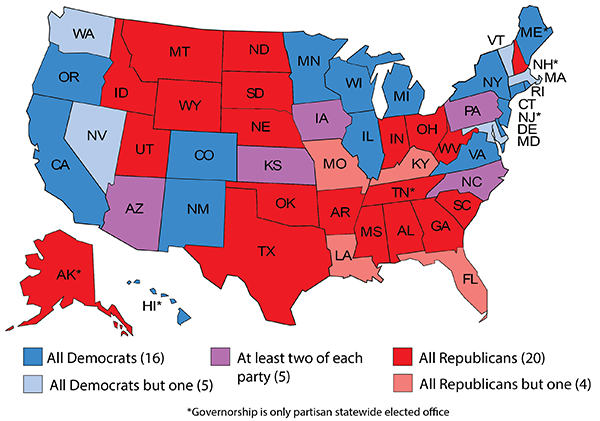

Of the 50 states, Republicans have a monopoly on the statewide elected executive offices in 20 of them, while Democrats hold all of these offices in 16. This includes the six states that only have a single statewide elected executive officeholder (the governor). Five states have all Democrats except for a single Republican, four have all Republicans save a single Democrat, and just five have at least two members of each party in these offices (and there is a significant asterisk with one of these states, as we’ll explain below).

The roster of statewide elected officeholders in the states — including governorships and other posts — is shown in Map 1. This article updates an accounting of these offices done by Crystal Ball Senior Columnist Louis Jacobson last year.

A note on how we counted: We excluded some minor offices as well as non-elected offices and state Supreme Courts. We also excluded lieutenant governors unless they were elected separately in their own right (most are elected as part of a gubernatorial ticket). U.S. senators, even though they are elected statewide, are not considered here. No positions serving on multi-member commissions were included, even if some members are elected statewide. So, for instance, Colorado only has Democrats elected to its statewide executive offices, and that is noted on Map 1, but Heidi Ganahl (R) holds a statewide elected slot on the University of Colorado Board of Regents. She may run for governor or another statewide executive office next year as part of the Republicans’ bid to break up the Democratic monopoly on those offices.

Map 1: Party control of statewide elected executive offices

Source: Ballotpedia, Louis Jacobson

The one-party states align almost completely with the 2020 presidential results. Joe Biden carried all 16 of the states where only Democrats hold these statewide offices, although Wisconsin was decided by just six-tenths of a percentage point and Michigan was decided by a little less than three. Meanwhile, Donald Trump won 18 of the 20 all-Republican states. The exceptions were Georgia, which Trump lost by about a quarter of a point, and New Hampshire, which Trump lost by more than seven points but where incumbent Gov. Chris Sununu (R) easily won a third, two-year term. New Hampshire is one of the six states that has only one statewide elected office considered for the purposes of this article: The others are Alaska, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, and Tennessee.[1]

Texas, still all-Republican, already is holding one of the marquee statewide down-ballot races next year: state Attorney General Ken Paxton (R), who faces charges of securities fraud, is being challenged in the GOP primary by both former state Supreme Court Justice Eva Guzman and state Land Commissioner George P. Bush. Bush is the son of former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, and he has been handing out can koozies featuring him shaking hands with former President Trump along with a Trump quote: “This is the Bush that got it right. I like him.”

The number of one-party states went up in aggregate in 2020. Republicans flipped the open Montana governorship and defeated the last remaining Democratic statewide executive officeholder in West Virginia, then-Treasurer John Perdue, to put those states in the all-Republican column.

Meanwhile, Democrats flipped the open Oregon secretary of state’s office last year, shutting the Republicans out of statewide office there. However, Republicans did break up Democratic statewide office dominance in Pennsylvania, as they flipped the state auditor and state treasurer offices even as Democratic Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a likely gubernatorial candidate next year, won a second term and as Joe Biden carried the state by a little more than a point (the Pennsylvania governorship is elected in midterm years, the other offices in presidential years). In 2016, Democrats swept these three offices even as Trump was carrying the state.

The Keystone State is one of five states that have at least two statewide elected officeholders from each party. It is joined in that category by two of the other very closely-contested presidential states from last year, North Carolina and Arizona. The Tar Heel State elects 10 statewide officeholders in presidential election years. Republicans hold six of these 10 offices: None changed hands last year, but many (particularly some of the Democratic-held ones) were extremely close. Kansas is the state noted above as an asterisk, because it really only has one Democrat elected statewide in her own right: Gov. Laura Kelly, who won in 2018. However, the state’s elected treasurer position opened up when its former occupant, now-Rep. Jake LaTurner (R, KS-2), won election to the U.S. House. So Kelly was able to appoint her running mate, Democratic Lt. Gov. Lynn Rogers, to the post. Rogers is included here because he holds an elected office, even though he wasn’t actually elected to it.

The outlook for 2021-2022

Let’s get back to the aforementioned candidate announcements. Galloway’s decision not to run again for Missouri state auditor seems very likely to lead to the Republicans adding another statewide sweep: Missouri has become very Republican over the course of the last couple of decades, as evidenced by the GOP winning the state in every presidential election this century and, more recently, by Galloway losing by 16 points to Gov. Mike Parson (R-MO) in last year’s election. Fried’s decision to run for governor also imperils Democratic control of her post, Florida commissioner of agriculture. Fried narrowly won in 2018 even as Democrats lost close statewide races for governor and Senate. She has to contend with at least one other major Democratic candidate, Rep. Charlie Crist (D, FL-13), for the right to challenge Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) next year. We would expect Republicans to be favored in all the statewide races in Florida next year, given that Democrats could only capture one in 2018 despite being on the right side of a national midterm wave.

In Arizona, Hobbs’ decision to seek the governorship leaves her secretary of state post open, although there is another Democratic incumbent, state Superintendent of Public Instruction Kathy Hoffman, who will be seeking a second term and could allow the Democrats to hang onto a statewide post even if the election otherwise goes poorly for them. There will be a lot of flux in the Arizona statewide races, because Gov. Doug Ducey (R) is term-limited, and state Attorney General Mark Brnovich (R) and Treasurer Kimberly Yee (R) are running for senator and governor, respectively.

Beyond these states, we could see others fall into the one-party column. With Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) term-limited in Maryland, Democrats have a golden opportunity to take all the statewide offices in that overwhelmingly Democratic state next year. Democrats might be able to do the same in Massachusetts, where Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA) is mulling running for a third term. The lone Republican statewide official in Nevada, Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske, is term-limited, although Nevada is a highly competitive state even though Democrats have more often come out ahead in recent years, and Republicans could make inroads there in other offices depending on the circumstances. Of the 20 states with currently all-Republican statewide elected executive officeholders, Georgia stands out as one where Democrats could hypothetically break the Republican lock on these offices, as 2018 gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams (D) seems likely to challenge Gov. Brian Kemp (R) in a rematch and Democrats should otherwise be able to credibly contend for other offices. New Hampshire’s governorship would also be a Toss-up if Gov. Sununu runs for U.S. Senate.

One would expect Republicans to make major plays for all the statewide offices in Michigan and Wisconsin, the competitive Upper Midwest states where Democrats currently hold all the offices. Democrats are defending Virginia’s three statewide offices this November. Kansas will be a major Republican target as well: The state treasurer office will be back on the ballot and, more importantly, Gov. Kelly will be trying to win a second term in what is still a very Republican-leaning state. Elsewhere in the heartland, Iowa’s six statewide offices (including the governorship) will all be up next year. Despite the state’s turn toward Republicans in recent years, Democrats still hold half of those offices: state Treasurer Michael Fitzgerald has held his post since 1983, while state Attorney General Tom Miller has held his since 1979, with a four-year break from 1991 to 1995 after losing a gubernatorial primary. Fitzgerald is 69 and won by double digits in 2018; Miller is 76, and he didn’t even have a Republican opponent in 2018. Their decisions on whether to run for another term are of course important. The other statewide Democrat is Auditor Rob Sand, who is just 38 and won his first term in 2018. He may follow the lead of Hobbs and Fried and run for governor this cycle.

While there are of course scenarios where the minority party could break through in some of the states where one party holds sway — several are noted above — let’s specifically look at the 14 where both parties currently hold at least one of these offices.

Kentucky and Louisiana, where Democrats hold the governorship but nothing else, are not on the ballot again until 2023. Republicans should be heavily favored to win the governorship in Louisiana, where Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) is term-limited. Gov. Andy Beshear (D-KY) can seek a second term, and presumably will have a hard race. But these states will endure as split until at least after this midterm. So too will North Carolina and Washington state, which don’t have these races on the ballot this cycle, and Pennsylvania, where Shapiro will either become governor or remain attorney general, guaranteeing the Democrats control of at least one of these offices until 2024 (assuming he does not resign as AG). So that’s at least five states that will be split following 2022, barring something unforeseen.

As noted above, Republicans could very well sweep Florida and Missouri now that the Democrats are not defending their single statewide office with incumbents. Democrats could sweep Maryland and maybe Massachusetts. Popular Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT), the lone Republican elected in Vermont, has to run every two years. If he were to not run again, Democrats could sweep there.

Arizona, Iowa, Kansas, and Nevada are split states that all should feature competitive races next year. Sweeps can’t be ruled out in any of them.

The bottom line is that we may have even more one-party statewide executive states after 2022 than we have now, which would fit in with a larger trend toward one-party dominance in many of the states.

Footnote

[1] There is actually an effort in Maine to allow voters to pick the state’s attorney general, secretary of state, and treasurer, but it appears that effort has stalled in the state legislature, which currently decides who occupies these offices.