KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The polls were basically correct in Iowa, as Donald Trump dominated the kickoff caucus.

— Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley finished second and third, respectively, in a scramble for second, but they were both so far behind Trump—about 30 points apiece—that it was hard to find much silver lining for either of them.

— Compared to 2016, Trump ran much better with key demographic groups—and that was particularly true among the GOP’s most conservative and evangelical voters.

— New Hampshire is a bigger test for Trump, as its electorate is more favorable to Haley than Iowa’s was. But Trump can further confirm his imposing status by winning there, as non-incumbent Republicans have struggled to win both Iowa and New Hampshire in the same cycle.

On Iowa

There were no real surprises in Iowa on Monday night, as the kickoff contest of the Republican presidential nominating season unfolded in almost exactly the way that polls suggested. Former President Donald Trump got about half the vote, with the race for a very distant second place coming down to a close contest between Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) and former Gov. Nikki Haley (R-SC). According to results as of early Tuesday morning, Trump was at 51%, with DeSantis nabbing second place at 21% and Haley finishing close behind at 19%. The fourth-place finisher, businessman Vivek Ramaswamy, got a little under 8% and immediately dropped out. Nobody else got even 1%.

Late polls did show Haley edging ahead of DeSantis for second, but they were closely-bunched enough that DeSantis finishing ahead shouldn’t be considered a shock—indeed, leading Iowa pollster J. Ann Selzer had Haley narrowly ahead in her poll, but she noted a lack of enthusiasm among Haley’s supporters that made Selzer think Haley’s hold on second was loose. That ended up being correct, and turnout—perhaps because of horrible weather, perhaps because of a lack of competition, perhaps because of a lack of party intensity, perhaps for other reasons—was weaker in terms of raw votes cast (about 110,000) than not only the high turnout 2016 contest (in which about 187,000 votes were cast) but also the 2008 and 2012 contests, when about 120,000 apiece were cast. Caucuses are hardly a boon for participation overall—there were nearly 200,000 votes cast in 2022’s largely sleepy Republican midterm primary in Iowa, close to double the votes cast in this year’s caucus.

The result for Trump was solid. He performed at about where the polls had him—polling averages had him getting about 52.5%, and he ended up at 51%—but Haley, who is his biggest threat in New Hampshire, couldn’t translate her late positive momentum into a second-place finish. DeSantis is still in the race, although we honestly don’t know if him dropping out would actually boost Haley all that much—maybe she would get more of his support, but Trump probably would get some too, and Trump just got about half the vote in Iowa and gets more than that in national surveys.

Trump’s Iowa coalition is obviously a lot bigger than it was in 2016, when he got just 24%, losing to Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX). But it is also more conventionally Republican. Here’s what we mean.

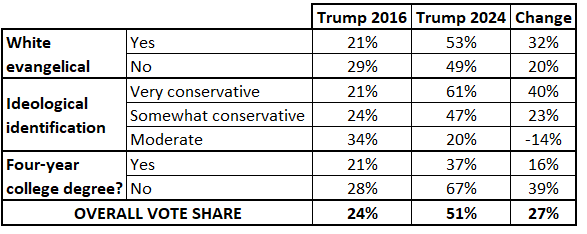

Table 1 compares the 2016 and 2024 Iowa entrance polls, both of which were conducted by Edison Research for a variety of media outlets. They are called “entrance” polls, instead of “exit” polls, because caucus participants were asked who they planned to caucus for before entering their caucus sites. Trump’s overwhelming lead in the entrance poll helped media outlets call the caucus quickly for Donald Trump, much to the ire of, in particular, the DeSantis campaign.

We picked three key demographic characteristics to illustrate the change in Trump’s coalition from his first-ever election, the 2016 Iowa caucus, to now: ideology, education, and religion.

Table 1: Trump support, 2016 vs. 2024, by key demographic characteristics

Source: Edison Research 2016 and 2024 Iowa entrance polls conducted for several media organizations.

Notice that Trump generally did way better in all of these categories (except one) in 2024 compared to 2016: More than doubling your support will do that. But also notice that Trump’s relative weakness with core GOP voters in 2016 turned into strengths in 2024. In 2016, Trump did worse with non-evangelical Christian white voters than evangelical ones, and he did worse with very conservative voters compared to somewhat conservative ones. This time, he did slightly better with evangelicals than non-evangelicals and better with those who described themselves as very conservative than those who described themselves as just somewhat conservative. This change was particularly helpful as white evangelical Christians outnumbered non-evangelical whites roughly 55%-45% in the Iowa electorate as reported by the entrance poll, and very conservative voters made up 52% of the electorate, compared to just 37% for somewhat conservative voters and just 9% for moderates. Speaking of moderates, that’s the one group in Table 1 where Trump’s support declined—Haley won this group 63% to just 20% for Trump, with DeSantis at just 7%. It didn’t matter because moderates were such a small part of the electorate in Iowa (but they will be more impactful in New Hampshire). Trump inspiring conservatives but alienating moderates is of course very helpful in a primary setting, but it’s a challenge for a general electorate in which the less ideologically-defined Trump of 2016 was likely a better fit for swing voters than the current version of Trump.

In both 2016 and 2024, Trump did better with voters who did not have a four-year degree compared to those who did, but note that massive jump—39 points—with the non-college group, winning about two-thirds of them. The college-educated group was more of a muddle, but Trump finished first with them too, getting 37% to Haley’s 28% and DeSantis’s 26%. That’s more than good enough for Trump, as we’ve previously noted when discussing primary polls that showed Trump dominating with non-college voters and doing perfectly fine among non-college voters.

This showed up in the results, as Trump appeared to win all but one county—Johnson County, both the most college-educated and most Democratic county in the state (it’s the home of the University of Iowa). As of publication, Haley led Trump there by just a single vote. Trump won Dallas and Story counties, the other most highly-educated counties in the state, albeit with sub-40% pluralities. Haley’s college/moderate-heavy coalition also showed up in the actual results: Johnson, Story, and Dallas were her three best counties. DeSantis’s coalition is a little less clear-cut, although he ran ahead of his statewide share in some of the places Haley did well, like Story and Dallas counties, and he narrowly beat her in Polk County (Des Moines). DeSantis’s best county, 31%, was Sioux in northwest Iowa, which we highlighted in our preview as an evangelical hotbed (indeed, it is the most white evangelical county in the state, according to the Public Religion Research Institute). But Trump still won Sioux by double digits—it was his worst county in the entire state in 2016, as he got just 11% there, but Trump was up to 45% there on Monday. That 34-point jump was larger than his overall statewide improvement, and it mirrors Trump’s improvement statewide among evangelicals, as noted in Table 1. In other words, DeSantis has some appeal to evangelicals, but Trump has more appeal—and way more appeal than Trump himself had in the early stages of the 2016 campaign.

We now look ahead to New Hampshire. DeSantis was already campaigning in South Carolina on Tuesday morning, an acknowledgement of his meager polling position in the Granite State (although DeSantis is not ignoring New Hampshire and was doing another event there later on Tuesday). The test for Haley is to win or at the very least come close in New Hampshire, given that its more moderate and less evangelical electorate is demographically friendlier to her than the more conservative and evangelical Iowa electorate was. Because of Haley’s potential strength in New Hampshire, Trump was never going to score a knockout blow to the rest of the field in Iowa. But a win in New Hampshire following a win in Iowa would give him a sweep of the opening two contests—something no one in a competitive Republican race has done since unelected incumbent Gerald Ford did it in 1976 (and even that comes with an asterisk, as the Iowa caucus featured just a variety of sample precincts that year, which we noted in our preview last week). More broadly, sweeping Iowa and New Hampshire would show that Trump retains a good amount of appeal across the Republican Party—not uncontested incumbent levels of support, but more than enough support to finish well ahead of his rivals in different kinds of states.