| Dear Readers: This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, which features short updates on elections and politics.

— The Editors |

The VA-GOV Polls: 2013, 2017, and now

It is an unusual quirk of the polling in the 2013 and 2017 Virginia gubernatorial races that the average for 2013 would have performed better if it had been trying to predict the 2017 results, and the average for 2017 would have been markedly closer to the final results had it been applied to 2013.

As it was, the actual average in both elections ended up being several points off. In 2013, the polls generally overstated the Democratic advantage. In 2017, the polls generally understated the Democratic advantage.

The final RealClearPolitics average of the 2013 Virginia gubernatorial race showed Terry McAuliffe (D) leading by 6.0 points over Ken Cuccinelli (R), but McAuliffe only ended up winning by 2.5 points. Four years later, Ralph Northam (D) had a 3.3-point lead in the final RealClearPolitics average, but he went on to win by 8.9 points over Ed Gillespie (R).

Libertarian candidates complicated the polling in both years, although more so in 2013, when Robert Sarvis was at nearly 10% in the final average of the three-way polls, with McAuliffe’s lead a bit bigger in that three-way average (6.7 points). As it was, Sarvis polled (9.6%) better than he performed (6.5%). Four years later, Cliff Hyra was at 2.3% support in polls that named him, but he ended up at 1.1% in the actual voting.

Polling in this year’s race, between former Gov. McAuliffe (D) and businessman Glenn Youngkin (R), has shown a competitive race led by McAuliffe. In 5 polls released since late August, McAuliffe leads 47.2%-42.8%, for an average edge of 4.4%. The candidates had their first debate last Thursday at the Appalachian School of Law in far western Virginia. We didn’t think either candidate did anything that changed the trajectory of the race — something that is hard to do in debates that few truly persuadable voters actually see.

The one poll that has shown Youngkin leading came from his own campaign, which showed him up 48%-46% in early September (that poll is not included in the RealClearPolitics average). Youngkin’s lead in his campaign’s poll was contingent on the inclusion of the third candidate in the race, Princess Blanding, as a named candidate in the poll. Blanding, a progressive listed on the November ballot, garnered 3% support, and she has gotten 2%-3% of support in some other polls when explicitly named as an option for poll respondents. Third-party candidates often perform worse than they poll, both in the last two Virginia gubernatorial races and in other races elsewhere, so we wouldn’t expect Blanding to ultimately reach what she’s polling when pollsters name her as a candidate. McAuliffe and Youngkin were tied on the two-way ballot in the Youngkin campaign poll, conducted by the GOP firm WPA Intelligence.

One of the very recent nonpartisan surveys, from the Washington Post and George Mason University’s Schar School, showed McAuliffe up 50%-47% among likely voters, but up 49%-43% among the wider universe of registered voters. In other words, this poll suggests that McAuliffe has an enthusiasm problem, in that fewer of his voters made it through that poll’s likely voter screen than Youngkin’s. So a higher turnout is likely the goal for McAuliffe, whose party performed much better in 2017 and 2018’s higher-turnout statewide elections than they did in lower-turnout 2013 and 2014.

Granted, California is a much different and much more Democratic state than Virginia, but Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) sometimes faced a similar problem in some polls of his recent recall election there. Ultimately, Newsom got Democrats engaged, and it appears that he performed quite well in the recall: His lead stands at a little over 25 points with about 11.6 million votes counted statewide. Total turnout may end up near or at about 13 million given what California has reported about the remaining uncounted ballots. But so long as those uncounted votes aren’t overwhelmingly in favor of the recall, it appears that pre-election polling will have undershot Newsom’s eventual margin of victory — the final FiveThirtyEight average showed the recall being defeated by roughly 16 points. Newsom won in 2018 by roughly 24 points. We’ll take a look back at the results when they are finalized.

That said, the Virginia experience of both 2013 and 2017 shows that polling error, to the extent it happens, can break either way. We continue to rate the gubernatorial race as Leans Democratic.

Oregon redistricting: Tense times as Democrats attempt a gerrymander

Going into this week, it looked like Oregon, which gained a seat in the 2020 census count, might have become the first state of this redistricting cycle to officially enact a congressional plan. On Monday, the legislature met for a special session with the goal of tackling the process.

As the session got underway, though, it became clear that Democratic state House Speaker Tina Kotek — who is also a candidate for governor next year — would renege on a deal that she made earlier this year with state House Republicans. Kotek has instead pushed for her own party’s congressional and legislative maps.

Still, Democratic leadership, at least from a logistical standpoint, cannot completely ignore the minority party without possible consequences. Under Oregon’s legislative rules, unless a quorum is met, business cannot take place. So if enough Republican legislators “walk out,” they could deny a quorum. This is a tactic that they have used in recent sessions on other matters, and Kotek sought to mitigate this by making the now-seemingly defunct redistricting deal with Republicans earlier this year.

But GOP legislators may have some reason to show up. If no maps are enacted by Monday (Sept. 27), congressional line-drawing will fall to the courts, while Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan will be tasked with drawing the new legislative districts. Though this could lead to a more equitable congressional plan, would GOP legislators like to have Fagan drawing their districts? In something of a worst-case situation for state Republicans, Fagan could draw maps designed to augment the current Democratic majorities. If they pick up enough seats, Democrats could produce a quorum by themselves and perhaps even push a partisan congressional plan mid-decade.

As if this process wasn’t already hard enough to game out, COVID-19 has been another complicating factor: yesterday, there was COVID-19 exposure in the state capitol, which appears likely to push the drama into the weekend.

If Republicans show up when the legislature reconvenes, it will be a sign that the lawmakers — and governor — are on track to complete maps by the 27th, but if they “walk out,” it will be an indication that they’d prefer to roll the dice.

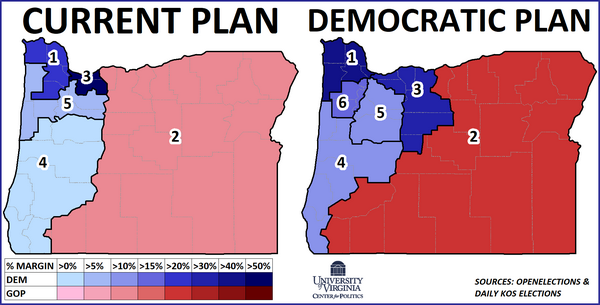

So, what would a potential Democratic congressional map look like? On Map 1, the current plan is on the left, while the plan that legislative Democrats prefer is on the right. For the entire decade, the existing plan has kept a 4-1 Democratic delegation — the proposal on the right would add another Democratic-leaning district. Map 1 is colored based on 2020 presidential results.

Map 1: Current vs Democratic-proposed Oregon plans

One of the more effective partisan changes in the Democratic plan is that Rep. Cliff Bentz’s (R, OR-2) eastern district becomes more of a Republican pack: Trump’s margin climbs from about a dozen points on the existing map to almost 25 points. Meanwhile, Democrats moved some of their voters in OR-2 into a friendlier seat. Specifically, OR-3, which is held by Democratic Rep. Earl Blumenauer and has long been a Portland-centric seat, would reach across the Cascades to grab the city of Bend in Deschutes County, a Trump-to-Biden county that has seen some Democratic trends in recent cycles.

Though OR-3 still retains much of Portland’s Multnomah County, it would no longer be the most Democratic seat on the map: as Rep. Suzanne Bonamici’s (D, OR-1) district expands its holdings in the county, Biden’s margin in OR-1 expands from 29% to over 40%. She and Blumenauer would still have utterly safe seats.

On the Democratic plan, the new 6th District was added just south of Portland: It contains the state capital, Salem, as well as some adjacent counties. Importantly, the proposed OR-6 has tracked closely with the state as a whole in recent elections: last year, Biden would have carried the district by 17 points (he won the state 56%-40%).

Reps. Peter DeFazio (D, OR-4) and Kurt Schrader (D, OR-5) have both overperformed in their light blue districts for much of their careers, but their 2020 margins were more tied to the top of the ticket, and both are vulnerable in 2022 under the current lines. Perhaps with this in mind, Democratic legislators made each of their districts several points bluer.

Schrader’s proposed new 5th District, though it appears to be a compact seat at first glance, is one of the more creative gerrymanders on the map. About 80% of its votes come from portions of Clackamas, Linn, and Marion counties — this part of the district was about evenly split between Biden and Trump last year. But OR-5 then reaches up to grab 20 heavily Democratic Multnomah County precincts that Biden won by a 60,000 vote margin. The result is a district that Biden carried by just under 15 percentage points.

Finally, DeFazio’s 4th District sheds some of its inland areas and moves further up the coast. Mappers ensured that this southwestern district retains its Democratic strongholds, the college towns of Corvallis and Eugene, which, electorally, have drowned out its reddening rural holdings. Last year, OR-4 basically mirrored the national vote (going 51%-47% Biden), but under the proposed map, it voted Democratic by a more comfortable 13-point margin.

So if the Democrats end up passing this plan by the 27th, they would be clear favorites in 5 seats, while Republicans would retain an ironclad grip on their sole seat — we’ll just have to see what legislative Republicans do in advance of the Monday deadline.