| Dear Readers: This is the fourth part of our multi-part series on congressional redistricting. Part One provided a national overview, Part Two covered several small-to-medium-sized states in the Greater South, and Part Three looked at four larger states in the South. This week, we’re analyzing the West Coast and the Southwest — in many of these states, redistricting is conducted by commissions. While commissions can be unpredictable, our general sense is that, from a partisan perspective, the region may end up as something of a wash, with Republicans perhaps slightly better positioned to make a small gain compared to Democrats.

We will cover additional regions in the coming weeks. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Independent redistricting commissions are most common out West.

— Democrats currently dominate the House delegations from the West Coast and Southwest, and that is likely to continue.

— However, Republicans may be able to make up a little ground, thanks in part to California losing a seat and Oregon gaining one.

— Democrats can gerrymander Nevada and New Mexico, but it will be difficult for them to squeeze an additional seat out of these small states.

Redistricting out West

The states of the West have often been on the cutting edge of American political reform movements. Prior to the passage of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote across the nation, several states had already approved women’s suffrage, and 10 of the first 11 states to do so were in the West: Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Washington, California, Arizona, Oregon, Montana, and Nevada (the lone exception was Kansas).

More recently, the West has also been in the vanguard of voting by mail. Oregon was the first state to switch to all-mail voting, and it has been joined by several other western states.

And the West is also a leader in independent redistricting commissions. Of the 10 states that we classify as having independent/nonpartisan congressional redistricting systems, seven are in the West: Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, and Washington (the others, back east, are Michigan, New Jersey, and Virginia, and only the New Jersey system was in place prior to this decade’s round of redistricting).

These commissions can work in different ways. The Washington state commission has developed a reputation for protecting incumbents, which likely helped Republicans, at least earlier in the last decade. The Arizona commission emphasized competitiveness last decade, which frustrated Republicans and aided Democrats. California’s commission tore up the state’s existing districts last decade, creating a map that ended up breaking heavily in the favor of Democrats (although, as we note below, political realignment was a major part of Democratic gains in California last decade).

In this week’s edition of our ongoing congressional redistricting series, we’ll be looking at the West Coast and the Southwest — specifically, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington. We’ll be looking at the remainder of the West, as well as some states in the Great Plains, next week.

The past couple of weeks, we’ve been looking at the Greater South, a region that Republicans dominate. But out West, Democrats dominate. Under the 2010s congressional apportionment, these seven states held 86 of the 435 House seats (20% of the total), and Democrats currently control 65 of those seats (76% of the total). Democrats hold an edge in all seven of these states, although that advantage is only 5-4 in Arizona and 2-1 in New Mexico. Joe Biden also carried all seven of these states, although Arizona and Nevada are swing states.

These seven states will continue to hold 86 seats based on the 2020 reapportionment, as California is losing a seat and Oregon is gaining one. We do not expect much to dramatically change in redistricting in these states, but this trade between California and Oregon may have the effect of netting the Republicans a seat.

Let’s take a look at these seven states in detail. But one important note before we begin: Later today (Thursday, Aug. 12), the Census Bureau is going to be releasing the actual, granular population data that will allow states to start drawing districts. In some or many instances, this actual data might look different than the 2019 estimates we’ve been citing in the course of our redistricting series. So we, and many others, are very curious to see what the actual numbers look like, and we’ll have more to say about it in future editions of our redistricting series and in our analysis of the actual redistricting maps that will emerge in the coming months.

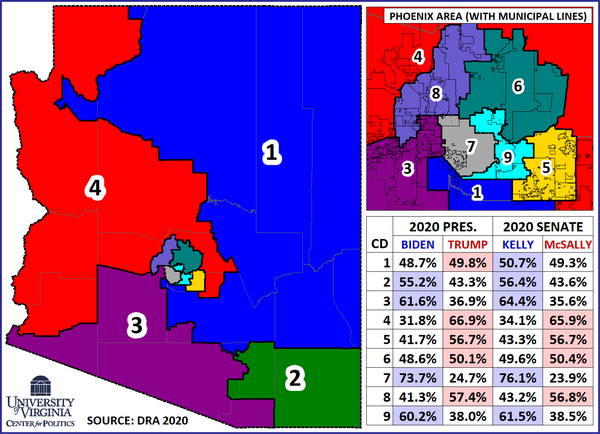

ARIZONA

Number of seats: 9 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 5-4 D

Current party breakdown: 5-4 D

Most overpopulated district: AZ-7 (Phoenix)

Most underpopulated district: AZ-2 (Tucson)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

Arizona not gaining a 10th seat was one of the biggest surprises of the 2020 congressional reapportionment. In fact, 2020 marked the first census since the 1950 round that Arizona did not gain at least one seat in Congress — the state’s growth in recent decades has been especially robust, as its population has doubled in the last 30 years, going from 3.7 million residents in 1990 up to about 7.3 million today.

Even with that type of growth, the Arizona map will continue to feature nine congressional districts. While some states have adopted redistricting commissions fairly recently, Arizona’s was established to draw maps immediately after the 2000 census, as voters approved the creation of a commission via a referendum that year. But last decade, the legitimacy of the commission was tested. In 2012, Arizona Republicans were frustrated after the commission-drawn map elected a 5-4 Democratic congressional delegation, even as then-President Obama lost the state by nine points in his reelection bid. Legislative Republicans charged that the commission’s authority was unconstitutional, and took their case to the Supreme Court. But the high court ruled that voters could transfer jurisdiction over redistricting away from legislatures, so the Arizona commission was upheld. Republicans believed that last decade’s tiebreaking member overly helped the Democrats and unsuccessfully tried to have her removed from the commission. This time, the GOP seems happier with the tiebreaker.

Nestled in the southeastern corner of the state, AZ-2 is the only district that currently does not contain any of Maricopa County (home to Phoenix, as well as over 60% of the state’s residents) — it is also the most underpopulated district, and it will need to pick up about 75,000 residents. It seems likely that the district will simply pick up some communities near Tucson, or perhaps expand its holdings in the city itself. Assuming its configuration stays similar, longer-term trends suggest the district will stay Democratic: after Mitt Romney carried it by nearly three percentage points in 2012, President Biden did so by about 11 points.

After last decade’s remap was finalized, many Republican complaints centered on the redrawn AZ-1. This vast rural district includes both the Hopi and the Navajo nations, in the northeastern corner of the state, but for 2012, it dropped much of heavily GOP Yavapai County. Democrats captured the seat in 2008 with then-state Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick. Two years later, Kirkpatrick lost to Republican Paul Gosar by 13,583 votes — Gosar carried Yavapai County by just over 20,000 votes.

As an aside, Kirkpatrick has one of the most interesting career arcs of any current member. For 2012, Gosar moved over to the redrawn AZ-4 (now the most heavily GOP seat in the state), while Kirkpatrick reclaimed the swingier AZ-1. Kirkpatrick, impressively, held on in 2014, then ran unsuccessfully for Senate in 2016 against the late Sen. John McCain (R-AZ). She then moved to a new district herself, winning AZ-2 in 2018 and 2020. She is retiring this cycle.

Though AZ-1 narrowly supported the GOP presidential nominees in 2012 and 2016, Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D, AZ-1) has represented the district since Kirkpatrick vacated it, in 2016. Ironically, last year, as the district finally voted blue at the presidential level, O’Halleran had the closest race of his career — he was held to a three-point win. It would not be hard for the commission to make AZ-1 more Republican-leaning: it could simply take in more of Yavapai County, or reach further into Pinal County, a fast-growing county that has seen sprawl from the Phoenix area.

It seems unlikely that the commission will alter AZ-3, a Hispanic-majority seat held by Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D, AZ-3). The 3rd District forms a triangle, running from Tucson to Yuma, then up to Phoenix. Similarly, it’s hard to see major changes to Democratic Rep. Ruben Gallego’s AZ-7 — it is also heavily Hispanic by composition, but it is a much more compact seat centering on downtown Phoenix.

Elsewhere in Maricopa County, it is hard to game out exactly what the commission will do in the suburban Phoenix seats. Since the state isn’t adding or losing any seats, the commission could take a minimal change approach. In 2020, Democrats targeted Rep. Dave Schweikert (R) in AZ-6, a district that includes much of Scottsdale — he held on 52%-48%, so any similar seat could be swingy. On either side of AZ-6, Reps. Andy Biggs (R, AZ-5) and Debbie Lesko (R, AZ-8) both won by close to 20 points last year, and each would be favored under similar lines (Biggs has been mentioned as a potential statewide candidate in 2022, but any competent Republican could hold his seat).

If the commission prioritizes creating competitive seats, it may unpack AZ-9, giving its Democratic voters to adjacent districts. AZ-9, which sits east of Phoenix and includes communities like Tempe and Mesa, was created for 2012. Initially, it was a true bellwether seat, as it basically matched the national popular vote that year — but in 2020, Biden cleared 60% in the district. Now-Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) was the 9th District’s first representative — when she vacated it to run for Senate in 2018, then-Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton ran as a Democrat and held the seat by a 61%-39% margin. In fact, the only Republican to ever carry AZ-9 in a statewide race was the late Sen. McCain in his 2016 race against Kirkpatrick.

Map 1 shows an Arizona map with minimal changes, although the marginal AZ-1 flips from a narrow Biden-won seat to a narrow Trump-won seat, while AZ-6 takes in all of Scottsdale and gets slightly more competitive (but is still a Trump-won seat).

Map 1: Hypothetical Arizona map with minimal changes

Realistically, Arizona’s next congressional map could lead to anything from a Democratic gain of one seat to a GOP gain of two seats.

CALIFORNIA

Number of seats: 52 (down 1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 38-15 D

Current party breakdown: 42-11 D

Most overpopulated district: CA-42 (Western Riverside County)

Most underpopulated district: CA-28 (Westside LA/Hollywood)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

The U.S. House of Representatives reached its current-sized voting membership of 435 after the 1910 census, and it has had the same-sized membership ever since, with the exception of a temporary expansion to 437 to account for Alaska and Hawaii becoming states in the late 1950s.

In that initial 435-seat apportionment for the 1910s, California had 11 House members — tied with Iowa, Kentucky, and Wisconsin. The Golden State now has nearly five times that number of members (53), although the state’s explosive growth has slowed in recent years. The state did not add any seats in the 2010 reapportionment round, which was the first time it failed to add a seat following a decennial census.

This most recent reapportionment represented a new, dubious first for California — the state is actually losing a seat, going from 53 to 52, though it still has by far the biggest House delegation (Texas will be second at 38 seats).

The loss of a seat will force California’s independent redistricting commission to chop a district. Beyond that, it’s unclear how much the commission, which is in charge for the second time after voters created it in 2010, will tweak the lines.

The commission, which by law cannot take partisan data or incumbent residence into account, dramatically changed the state’s map a decade ago. That new map put 27 incumbents into 13 districts and created 14 with no incumbent; seven incumbents retired, and another seven lost either to members of their own party or members of the other party (California uses a top-two election system, in which the top two finishers in an all-party first round of voting advance to the November general election). The commission injected some competitiveness into a state that had hardly any of it under a Democratic-drawn incumbent protection map in place for the 2000s: Just a single seat switched hands that entire decade, as Democrats started the decade with a 33-20 edge that became a 34-19 advantage. Democrats immediately netted four seats in the 2012 election, and they were up to a lopsided 46-7 edge by the 2018 election. Republicans recovered some of those seats in 2020, clawing back four Biden-carried districts. Four of the nine Biden-won seats held by Republicans are in California, including the only three that Biden won by double-digits: Reps. Mike Garcia (R, CA-25), Young Kim (R, CA-39), and David Valadao (R, CA-21) all hold districts that Biden carried by about 10 points apiece. The fourth Biden-district California Republican, Rep. Michelle Steel (R, CA-48), holds a much more marginal seat (Biden won it by just 1.5 points). So one of the big questions about the commission is whether the commission will merely tweak the last decade’s map, given that it was already drawn by a commission as opposed to legislators, or whether the members will take a wrecking ball to the existing map, much like the commission did a decade ago. This question is unanswerable at this point (at least from our perspective).

California was once known for hard-edged gerrymanders. Congressional scholar David Mayhew has noted that a California Republican gerrymander in advance of the 1952 election (along with one in New York) contributed greatly to the Republicans winning a slim House majority in that election, which was one of only two House majorities the Republicans won in a more than six-decade stretch from the early 1930s to early 1990s (the other came in 1946). More recently, California Democratic power broker Rep. Phil Burton crafted a strong gerrymander after the 1980 census, pushing a 22-21 Democratic delegation to a 28-17 edge. Voters threw out the map in a 1982 statewide ballot issue, but Burton crafted another, similar gerrymander that outgoing Gov. Jerry Brown (D-CA) — then serving his first eight-year stint as governor — signed right before leaving office. If Democrats still retained gerrymandering power in California — and they would have it even if Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) is ousted in a recall next month because Democrats hold veto-proof state legislative majorities — they likely could squeeze several more seats out of the state by hurting some or all of the Biden-district Republicans and also potentially going after at least one of two prominent Central Valley Republicans: House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-23) and Rep. Devin Nunes (R, CA-22), the former chairman of the Intelligence Committee.

But Democrats do not have that power. Rather, the commission will be drawing the lines.

Now, it is fair to wonder whether Democrats will end up with something of a de facto edge on the commission. A decade ago, Democrats gained advantages in the process through out-organizing Republicans, as ProPublica noted at the time. Additionally, California is an overwhelmingly Democratic state, so even on a commission with five Democrats, five Republicans, and four members not affiliated with either party, one might expect the commission to lean Democratic to some extent, argues independent California pollster Adam Probolsky: “We have a progressive state. So even though the commission is mandated to have No Party Preference voters, remember, independent voters look and think just like their neighbors — they just don’t have loyalty to a party. So those independents are going to lean progressive.”

All that said, it would also be unfair to describe the last decade’s map as a Democratic gerrymander. Rather, it was a map that created a number of competitive seats that Democrats were able to capture, and it also created a number of safe Republican suburban seats in Southern California that became much less Republican over the course of the decade, to the point where Democrats were able to win several of them. For instance, Joe Biden did 15 points better than Barack Obama did in 2012 in both San Diego and Orange counties, which are the second and third-largest sources of votes in the state and where Democrats flipped several House seats last decade. A lot of that is realignment, not gerrymandering.

One thing that does stand out in the state’s demographics is that many districts in the Los Angeles area are underpopulated. Scott Lay, who produces The Nooner newsletter on California state politics, suggests that one possibility is that an East Los Angeles district may be eliminated, with the districts held by Reps. Grace Napolitano (D, CA-32) and Lucille Roybal-Allard (D, CA-40) as possibilities (both are in their 80s, so either or both could retire). One other possibility is that Rep. Karen Bass’ (D, CA-37) district west of downtown could be eliminated if she decides to run for mayor of Los Angeles, as has been recently rumored — that would be a way to effectively protect all the other incumbents (readers will remember that Bass was one of Joe Biden’s reported vice presidential options). Darry Sragow, publisher of the California Target Book, recently noted that LA County contains all or part of 14 congressional districts, and that the ideal population size for California districts this decade will be about 760,000 people. Combined, the 14 LA County districts are currently about 575,000 people short of that target, meaning that “It is almost certain that the one seat California must give up will come from there.” (Although, remember, we’re working off census estimates, not the actual census numbers, which are coming out later today.)

Democrats would surely prefer the eliminated district come from elsewhere in the state, with the Central Valley as a candidate.

Assuming a Democratic LA County seat is cut, perhaps Democrats can make up for that by beating one or more of the Biden-district Republicans — Garcia seems the most vulnerable to us, in part because of a conservative voting record (he backed both objections to the Electoral College certification in January) — or by getting positive district alterations elsewhere. That said, the commission is difficult to handicap, so we’re just going to have to wait and see.

HAWAII

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-0 D

Current party breakdown: 2-0 D

Most overpopulated district: HI-1 (Honolulu)

Most underpopulated district: HI-2 (Half of Oahu/remainder of islands in state)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

One could make a case that Hawaii is trending Republican: Barack Obama won the state of his birth by 45 points in 2008, and Joe Biden won it by just 29 in 2020. But it would not be a very good case, particularly because if you started in 2004, when George W. Bush came within nine points of carrying the Aloha State, you could argue the opposite.

Only two Republicans have ever won House elections in Hawaii: Pat Saiki won two terms in the late 1980s, and Charles Djou won a flukish, all-party special election in 2010, but lost the regular election later that year.

The state’s bipartisan redistricting commission will have to make some slight adjustments to account for population (the Honolulu-based 1st District will have to shed a little population to HI-2, which covers the rest of the state), but we otherwise wouldn’t expect much to happen here. Biden won each district by almost identical margins (a shade under 30 points apiece), so they are politically similar. Democrats are so dominant in Hawaii at the state level that Republicans only hold one seat in the 25-member state Senate.

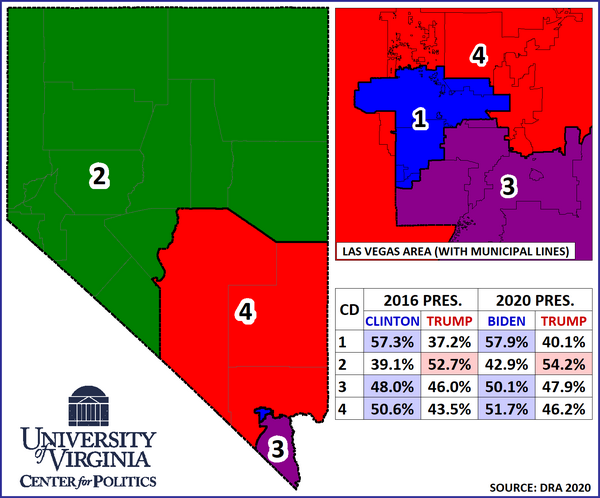

NEVADA

Number of seats: 4 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-2 split

Current party breakdown: 3-1 D

Most overpopulated district: NV-3 (Southern Clark County)

Most underpopulated district: NV-1 (Las Vegas)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Split

Compared to the post-2010 round of redistricting, Democrats have gained control of Nevada, but probably aren’t in a position to add more seats. Ten years ago, with a Democratic legislature and a Republican governor, a panel of three special masters were tasked by a judge to draw the lines. At the time, the state was adding a fourth seat, which most observers expected to lean Democratic, which ended up being the case.

In 2011, the court-ordered plan kept a heavily Democratic Las Vegas seat, a GOP-leaning northern seat, and retained a swingy seat in Las Vegas’ southern suburbs. The new seat, NV-4, was added in the northern Las Vegas area, and included a sampling of rural “cow counties.”

Though Democrats, as expected, won the new NV-4 in 2012, it became something of a cursed seat. Then-state Sen. Steven Horsford, a Democrat, was elected as its first member. Then, as the red wave of 2014 hit Nevada especially hard, Horsford lost to then-state Assemblyman Cresent Hardy, a Republican. Hardy was defeated himself the next cycle by Democratic state Sen. Ruben Kihuen. Faced with sexual misconduct allegations, Kihuen did not run again in 2018. Horsford made a comeback in 2018, beating Hardy by a 52%-44% margin in a rematch that year. Horsford was reelected in 2020, though by a closer 51%-46% vote — this was the first cycle since its establishment that NV-4 reelected its incumbent.

Going into last round’s redistricting cycle, Republicans held NV-3 with then-Rep. Joe Heck (R, NV-3), a first-term member who, on the campaign trail, emphasized his Army service. In 2010, Heck narrowly won his seat by defeating Rep. Dina Titus (D, NV-3), in what was, at the time, the most populous congressional district in the nation. When Heck ran for Senate in 2016, he lost to now-Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV), and was replaced by Democrat Jacky Rosen, a first-time candidate. Rosen successfully made the jump to the Senate in 2018, and Susie Lee (D) — who had lost a primary for NV-4 in 2016 — held NV-3. Lee was reelected in 2020, though by only three percentage points.

Shoring up the 3rd District will almost certainly be a priority for Democrats. As it is, NV-3 is among the most closely divided districts in the county: at the presidential level, it supported Barack Obama in 2012, Donald Trump in 2016, and Joe Biden in 2020, but none of its winners cleared 50% of the vote.

As Map 2 shows, Democrats could unpack NV-1, which is a reliably blue seat that encompasses downtown Las Vegas. After her loss to Heck, Titus switched districts and made a comeback in NV-1. Titus’ district gets slightly redder, compared to the current map, but Lee and Horsford are each given friendlier seats. Within Clark County, aside from a few larger cities, municipal splits are minimized in Map 2. Much of Las Vegas is in NV-1, NV-4 includes almost all of the more Democratic-leaning North Las Vegas, and NV-3 takes in all of Henderson, the county’s fastest growing, though still GOP-tilting, suburb.

Map 2: Hypothetical 3-1 Democratic Nevada map

On Map 2, Rep. Mark Amodei (R, NV-2), the sole Republican in the delegation, retains a favorable seat — his NV-2 has never sent a Democrat to Congress. Though his district includes Reno, a source of Democratic votes, mappers may be reluctant to draw a Las Vegas-based district that snakes up the California border just to grab some blue Reno precincts. In that scenario, the redder precincts in NV-2 would also have to go somewhere, and it’s likely they’d be put into a safely Republican seat anyway — so Map 2 essentially shows a cleaner 3-1 Democratic plan: NV-3 remains a swing seat (as does NV-4, to a lesser extent), but NV-3 flips from having voted for Trump in 2016 to narrowly voting for Hillary Clinton.

Though it’s possible to draw four Biden-won seats in Nevada, each district would track closely with the statewide vote — so no single district would be a slam dunk for Democrats. In a red enough cycle, four marginally Democratic seats could all potentially elect Republicans.

As veteran state journalist Jon Ralston sums up, though Democrats hold the redistricting pen, pleasing all three of their incumbents may be tricky. While Democrats could certainly come up with something more aggressive than Map 2’s plan, Lee and Horsford seem likely to get, at least, a slight boost.

NEW MEXICO

Number of seats: 3 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 2-1 D

Current party breakdown: 2-1 D

Most overpopulated district: NM-2 (South)

Most underpopulated district: NM-1 (Albuquerque)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Split

In New Mexico, which has had three seats since the 1980 census, Democrats face a choice: They can continue with two solidly blue seats, or they can risk trying to flip a third seat.

In 2011, with a Republican governor and a Democratic legislature, New Mexico’s congressional map was a compromise plan enacted by the state Supreme Court. In essence, it made minimal changes to the existing plan. NM-1 and NM-3, based in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, respectively, remained Democratic-leaning seats while NM-2, which includes Las Cruces and encompasses much of the Texas border, retained its GOP orientation.

Then-Rep. Steve Pearce (R, NM-2) was popular in the 2nd District — he held it for the first decade of the 2000s, then vacated it in 2008 to run for Senate. The 2008 New Mexico Senate race was a brutal one for Republicans. Pearce beat out then-Rep. Heather Wilson (R, NM-1) in a close primary, only to get clobbered by then-Rep. Tom Udall (D, NM-3) in the general election — it was a rare situation where all three of the state’s sitting members sought a single U.S. Senate seat. Democrats gained NM-2, as an open seat, in 2008, but in 2010, Pearce reclaimed the seat.

Pearce was reelected easily until 2018, when he launched another statewide run, this time for governor — which meant a replay of 2008 in NM-2. Pearce lost by 14 points to now-Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D-NM) while NM-2 flipped to Democrats. Xochitl Torres Small, a former Udall staffer whose husband was elected to the state legislature in 2016, narrowly beat out state Rep. Yvette Herrell for the open seat — two years earlier, NM-2 supported Trump by 10 points. Torres Small took 65% in Las Cruces’ Dona Ana County and kept Herrell’s margins down in the rural counties.

In Congress, Torres Small joined the Blue Dog Coalition, and tended to the oil industry, a major employer in the district. Still, Herrell ran for a rematch and got a boost from Trump’s showing in the district. While the then-incumbent president lost support in New Mexico’s other two districts, he improved by two percentage points in NM-2, carrying it by a dozen points — Torres Small ran better than Biden, but still lost by seven points.

Democrats could give Herrell a tougher district by redrawing NM-2 to take in the entire eastern half of the state. Though fellow first-term Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D, NM-3) may not like such a plan, as it could move some of her Santa Fe home turf into NM-2, it would give Democrats a good chance to reclaim all three districts. Democrats also could give districts 2 and 3 a greater chunk of Bernalillo County, though that may be met with some local resistance (the county is already split among all three districts, but the vast majority of it is in NM-1).

If Democrats wanted to try for a 3-0 map, they may want to ensure their two incumbents have enough of a cushion. Based on our calculations, they could draw two seats that would each be about 57% Biden, while the third would have only given him a small majority. Such a district would probably be winnable in a neutral national environment, but not a red wave year.

If Democrats pushed for a plan like this, they’d likely risk some public backlash: earlier this year, Gov. Lujan Grisham signed into a law a bill establishing a citizen’s redistricting commission that had bipartisan support. The redistricting commission’s recommendations will not be binding, so even if it suggests a status quo map, Democratic legislators would be free to pass their own plan, though doing so may look heavy-handed.

If New Mexico passes a minimal change plan, as it did last decade, the partisan balance of its delegation will very likely remain unchanged. Though NM-3, which includes a large rural swath of the state, has seen its Democratic advantage erode somewhat in recent cycles, Leger Fernandez made a strong debut last year — she was elected by 17%, running about even with Biden in the district. Similarly, in a recent special election, now-Rep. Melanie Stansbury (D, NM-1) won by a surprisingly wide 25-point margin. With Torres Small up for a job in the Biden Administration, it seems unlikely she’d run for a rematch in a similar version of NM-2, so Democrats would need to find another credible candidate to run against Herrell.

OREGON

Number of seats: 6 (+1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 4-1 D

Current party breakdown: 4-1 D

Most overpopulated district: OR-1 (Western Portland suburbs)

Most underpopulated district: OR-4 (Eugene/Southwest)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Split

Of the five states that touch the Pacific Ocean, Oregon is the only one left that lacks a redistricting commission. For 2012, a Democratic governor and a split legislature agreed on a minimal change plan — their job was, perhaps, made easier by the fact that the state was retaining its same five seats. But this year, the Beaver State, for the first time since the 1980 census, will be adding a new district.

Though Democrats nominally have a governmental trifecta, with the governorship and clear majorities in the legislature, Republicans are set to have a seat at the table. In a legislative compromise earlier this year designed to cut down on Republican stalling tactics on other legislative matters, state House Speaker Tina Kotek (D) announced that she would give the Republicans a greater role in redistricting. Assuming the deal holds, there will be an equal number of Democrats and Republicans on the House Redistricting Committee — so Democrats will not be able to pass maps out of the committee along a strictly party-line vote (although the deal applies only to the state House, not the state Senate, where Democrats will continue to hold sway on that chamber’s redistricting committee).

Of the state’s current incumbents, Reps. Earl Blumenauer (D, OR-3) and Suzanne Bonamici (D, OR-1) are likely the safest members. Though Blumenauer has a chunk of suburban Clackamas County, the bulk of his district comes from Portland’s Multnomah County. OR-3 typically gives Democrats over 70% of the vote, so he’ll have little to fear in any Multnomah County-based seat. Just to the west, Bonamici hails from Washington County, which includes suburbs like Beaverton and Tigard. Washington County itself has a population of roughly 600,000 — in other words, about 85% the population of the ideal congressional district — and Biden carried it 66%-31% last year.

Elsewhere in the state, Democrats will want to protect two of their members in more marginal seats. Reps. Peter DeFazio (D, OR-4) and Kurt Schrader (D, OR-5) have both shown impressive crossover appeal over the years, but both were held to just single-digit victories in 2020. DeFazio, who is the longest-serving member in the state’s current delegation (he was first elected in 1986), has a niche as a populist type of progressive. Both the University of Oregon (Eugene) and Oregon State University (Corvallis) are in DeFazio’s district, and these universities have provided him with a durable base of support, but the rest of the district has a more working class character — as in the Midwest, this demographic has moved more Republican. In 2010, despite the red hue of the year, DeFazio carried Coos County, a blue collar county that hugs the coast — 10 years later, he lost it by 17 points.

For Democrats, a simple solution to shoring up DeFazio may be to add Deschutes County to his district. This county, which contains Bend, is currently the most populous county in OR-2, the state’s sole GOP-held seat. Deschutes, with its relatively high concentration of college graduates, was a Trump-to-Biden county and seems increasingly dissimilar to the rest of OR-2, which is essentially the rural part of the state east of the Cascades. Though first-term Rep. Cliff Bentz (R, OR-2) carried Deschutes County by 51%-46% last year, given the trend of the area, he may prefer to take in the reddening parts of the current OR-4.

Overall, the biggest question about Oregon redistricting seems to be what will happen in the part of the state south of Portland but north of Eugene. Schrader, a Blue Dog who has pulled out clear wins even in some turbulent cycles for his party, is from Clackamas County, which includes suburban communities south of Portland. The mappers could give him all of that county, which supported Biden by 11 points last year, and some blue parts of adjacent counties, for a fairly secure seat. But would there be enough Democratic voters left over to ensure that the new seat votes blue?

Perhaps a compromise plan that could get some Republican support would be one that protects the current incumbents while adding a new swing seat — although with a seat at the table in redistricting, Republicans will likely push for a 4-2 Democratic map, giving them the state’s new seat. That outcome is our working assumption right now, but we all know what can happen to those who make assumptions, particularly about redistricting.

WASHINGTON

Number of seats: 10 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 6-4 D

Current party breakdown: 7-3 D

Most overpopulated district: WA-7 (Seattle)

Most underpopulated district: WA-6 (Olympic Peninsula)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

In Washington state, redistricting has been the prerogative of a bipartisan commission since the 1980s. In 2011, with the state gaining a seat, members of the commission ended up striking a deal: while the new seat would be a blue-leaning district in the Olympia area, WA-1, which was being vacated by now-Gov. Jay Inslee (D-WA), would become slightly more amenable to Republicans.

The new WA-10, as expected, elected a Democrat, but the party also retained its hold on WA-1 — now-Rep. Suzan DelBene claimed the redrawn seat 54%-46%, and has only won by larger margins since.

Both 2014 and 2016 were fairly sleepy election cycles in the Evergreen State, as no districts traded hands. But 2018 was more eventful. Rep. Dave Reichert (R, WA-8), a popular Republican who held a swing district in the Seattle suburbs, announced his retirement. Republicans ran a credible candidate in Dino Rossi — between 2004, 2008, and 2010, he came out on the losing end of three close statewide races, and was well-known — but the seat flipped to now-Rep. Kim Schrier (D), a physician who was then a first-time candidate. Schrier won by almost five points in 2018, though her margin was slightly reduced in 2020.

Though much of WA-8’s vote comes from the Seattle area, specifically King and Pierce counties, some rural counties — Chelan, Kittitas, as well as a small part of Douglas — were added to the seat for 2012, presumably to help Reichert. The three rural counties are all located in the Cascade Mountains, and don’t have especially much in common with the urban parts of WA-8. If the commission prioritizes incumbent protection, WA-8 may lose its eastern counties, though this would mean the district would lose its iconic Scottish Terrier Shape.

In 2018, Democrats made serious attempts at districts 3 and 5, but it’s likely that both seats will remain Republican-leaning. WA-3 has been based in southwestern Washington for the past several decades — once home to a vibrant timber industry, Democratic fortunes in the area have waned as the rural pockets of the district have fallen on harder times. In 2010, now-Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R) won the district over now-Lt. Gov. Denny Heck (D-WA) — even though 2010 was a rough year for Democrats nationally, Herrera Beutler was the sole Republican to flip a seat in a West Coast state. About 80% of the current WA-3 comes from Clark County (Vancouver) and a few peripheral counties — Clark County has a slight Democratic lean, but the surrounding areas have moved increasingly to the GOP — so it seems mappers wouldn’t have too much room to radically alter a Vancouver-centric seat.

In eastern Washington, the 5th District has sent Republican Cathy McMorris Rodgers to Congress since 2004 — from 2013 to 2019, she was Chair of the House Republican Conference, and remains an influential player in the caucus. In 1994, WA-5 was the site of one of the greatest recent congressional upsets, as Democratic Speaker Tom Foley lost his seat in that Republican wave year. Tellingly, the district has changed little since Foley left office — Democrats have a base in Whitman County (which houses Washington State University) and can sometimes carry Spokane County (the largest county in the district), but the rural counties usually give Republicans large majorities. McMorris Rodgers won by nearly 10% against a credible opponent in 2018, and her race completely fell off the radar in 2020.

WA-7 which takes up much of Seattle proper and is held by Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D), needs to shed nearly 60,000 residents. As WA-7 usually gives Democrats over 80% of the vote, this could essentially amount to an “unpacking,” as the districts around it could get bluer.

So overall, we don’t expect Washington state’s delegation to look much different in 2022 — only one seat changed hands over the last decade. If a similar plan is adopted, the next 10 years could be just as static. Democrats seem likely to be clear favorites in six districts, while their hold on WA-8 may be somewhat tenuous, depending on if it retains its eastern counties. Rep. Herrera Beutler, who voted for Trump’s impeachment, faces several more conservative challengers in her all-party primary, but we’d probably start any Republican there off as a favorite against a Democrat.

Conclusion

It feels like redistricting may reinforce the status quo in many of these states. That has been common in Washington. Democrats in Nevada may use their gerrymandering power to shore up the two competitive seats they hold, and they may be constrained from trying to draw a 3-0 map in New Mexico. The Arizona and California commissions are wild cards. The Republicans getting a seat at the table in Oregon may increase the likelihood that they can grab the state’s new seat.

So even in a region where Democrats dominate overall, the Republican position there may slightly improve in 2022, either through redistricting and/or the actual campaign next year.