| Dear Readers: This is the seventh part of our multi-part series on congressional redistricting. Part One provided a national overview, Part Two covered several small-to-medium-sized states in the Greater South, Part Three looked at four larger states in the South, Part Four considered the West Coast and the Southwest, Part Five swept through a sampling of Great Plains and Heartland states, and Part Six surveyed the electorally-critical Great Lakes region. This week, our final stop of the series will be in the Northeast — while national Democrats are certainly hoping that their New York counterparts deliver a favorable map, choices that both parties make in the smaller states could add up.

Though this is the last regional-level installment of our sweep through the country, we will conclude this series next week by offering some bigger-picture thoughts. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Democrats already control the vast majority of seats along the eastern seaboard from Virginia to Maine.

— New York offers Democrats their greatest gerrymandering upside of any state, but it is not guaranteed that they will maximize their holdings there.

— Virginia’s unproven new commission system makes redistricting there a mystery, although Republicans could re-take control of the state’s congressional delegation through a combination of redistricting fortune and strong electoral performance.

— Republicans in New Hampshire and Democrats in Maryland face notable gerrymandering decisions.

The Northeast and Mid-Atlantic

The Democratic Party is sometimes referred to as a “coastal” party. Indeed, Democrats hold a 53-15 edge in the combined U.S. House delegations of the West Coast states of California, Oregon, and Washington. But on the country’s Atlantic Coast stretching from Virginia Beach to eastern Maine, Democrats have an even larger advantage in the nine states in the region with more than one congressional district: 63-15. Add in one-district Delaware and Vermont, and the edge expands to 65-15.

So that means that in 2020, when Democrats won a narrow 222-213 majority in the House, the Democratic advantage in the Northeast (as defined here) and the West Coast was a combined 118-30. The Republicans have an edge of 183-104 in the rest of the country.

Democrats likely need to expand upon this edge in order to hold the House next year. We already looked at the West Coast states several weeks ago. Now we turn to the Northeast.

The nine states in this week’s redistricting update are, from north to south, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia. Joe Biden won all of these states, with his closest victory coming by seven points in New Hampshire. Democrats also hold a majority of the House seats in all nine of these states; that includes holding all of the seats in the six-state region of New England.

The Northeast includes what is the Democrats’ best chance to inflict real gerrymandering damage on Republicans: New York, although they will have to go around a new commission in order to do so. It also includes states where both parties will have to make important redistricting decisions, most notably Democrats in Maryland and Republicans in New Hampshire. And in our home state of Virginia, we’ll get to see how another new and untested commission system designed to make redistricting less partisan ends up working out.

CONNECTICUT

Number of seats: 5 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 5-0 D

Current party breakdown: 5-0 D

Most overpopulated district: CT-4 (Southwest Connecticut)

Most underpopulated district: CT-2 (Eastern Connecticut)

Who controls redistricting: Split

2012 control: Split

Connecticut is one of several states across the nation that used to feature strong competition at the U.S. House level but didn’t have much action last decade. Democrats won all five seats in all five election years last decade, and that was on a congressional map that was not gerrymandered to produce such an outcome.

A big reason for Connecticut’s transition from congressional battleground to Democratic bastion has been the long erosion of Republican strength in Fairfield County, the affluent, highly-educated part of the state that is closest to New York City and is the largest source of votes in the state. In 1996, Fairfield voted Democratic for president for just the second time since World War II (1964 was the other exception, as it so often was for historically Republican places in the North). By 2020, Fairfield was up to a 27-point margin for Joe Biden, the biggest margin it had given any Democrat for president possibly ever, or at least since at least the early 1880s (that’s as far back as Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections goes).

Former Rep. Chris Shays, the last Republican to win an election to the congressional district that covers Fairfield County, CT-4, is an exemplar of the moderate Republicanism that used to predominate in parts of the region. Elected in a 1987 special election, he first ran for reelection in 1988 — he claimed 72% while, up the ballot, George H. W. Bush took 57% in CT-4. Shays held on for three decades and was not seriously challenged until George W. Bush was in the White House. Finally, in 2008, as Barack Obama carried CT-4 by 20 points, Shays came up four points short against now-Rep. Jim Himes (D, CT-4).

A dozen years later, CT-4 was Biden’s best district in the state. Some of the Republican tradition in this part of the state still endures: Republicans recently won a special election for a state Senate seat that covers Greenwich and the New York border that voted heavily for Biden. However, state-level races in the district are typically much closer.

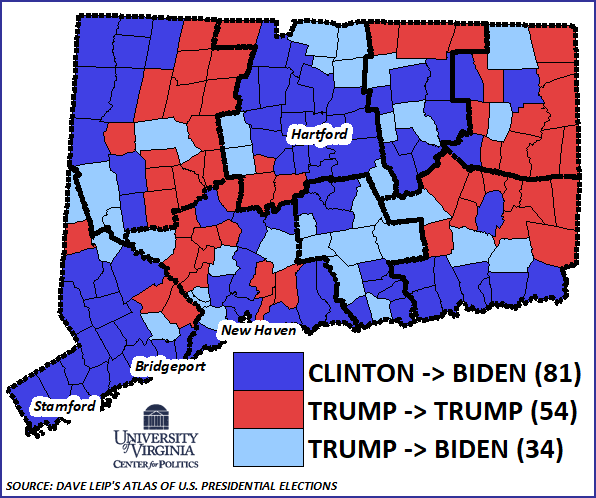

Some other parts of Connecticut flirted with Donald Trump in 2016 — he came within three points of winning Eastern Connecticut’s CT-2 and within about four of winning Northwest Connecticut’s CT-5, which was the state’s most competitive district at the U.S. House level in the 2010s. But, as it was in nearly every other congressional district in New England in 2020, Biden did better than Hillary Clinton, and he carried all five congressional districts in Connecticut by double digits. As Map 1 shows, in addition to holding all five congressional districts, Biden picked up almost three dozen towns that supported Donald Trump in 2016.

Map 1: Connecticut town loyalty, 2016-2020

The Nutmeg State has what amounts to a bipartisan redistricting process because Democrats lack the two-thirds state legislative majorities they need to draw the maps on their own. The two western seats, CT-4 and CT-5, are overpopulated to some degree, while the other three are underpopulated, though only CT-2 is significantly so. Courts could end up getting involved, as they did a decade ago when minimal changes were made to the map.

The bottom line in Connecticut is that under optimal circumstances, Republicans might be able to compete for one or more of its districts this decade. But if they do, redistricting likely will not have been a major contributor to that happening.

MAINE

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 2-0 D

Current party breakdown: 2-0 D

Most overpopulated district: ME-1 (Portland/Southwest Maine)

Most underpopulated district: ME-2 (Northern Maine)

Who controls redistricting: Split

2012 control: Split

The 2020 presidential election further strengthened the correlation between presidential and U.S. House results. According to Gary Jacobson, a leading U.S. House scholar, there was a .987 correlation between the presidential and House results in 2020 (on a zero-to-one scale), the highest such correlation since at least 1952. Just 16 districts produced a split result for president and for House. One of those handful of districts was in Maine, where Rep. Jared Golden (D, ME-2) won a second term. Golden won by six points against an overmatched opponent while Trump carried his district by almost 7.5 points. In 2022, Golden appears likely to once again face former Rep. Bruce Poliquin (R, ME-2), whom Golden narrowly defeated in 2018. The fate of ME-2 is what’s worth watching in Maine, as the state’s other district, held by Rep. Chellie Pingree (D, ME-1), is safely Democratic.

ME-1, which covers the state’s largest city, Portland, and some tourist-heavy areas along the state’s southern coast, has an above-average rate of four-year college attainment, an important predictor of Democratic trends in recent years. Meanwhile, ME-2 is below-average on college attainment and is more working-class. Due in large part to these demographic differences, Maine’s districts have taken divergent electoral paths.

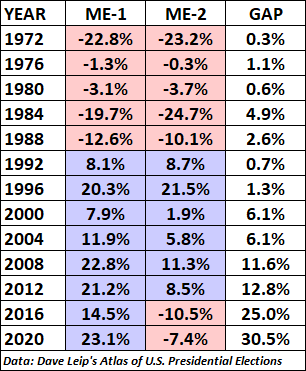

Since the 1972 presidential election, Maine has allocated its electoral votes by congressional district — during that time, geographically, the two districts have changed little. Table 1 considers presidential elections in Maine since 1972. Into the 1990s, the two were never more than five percentage points apart. The gap widened with the new century, and in 2020, Maine’s two districts were over 30 percentage points apart.

Table 1: Maine elections by congressional district, 1972-2020

ME-1 casts more votes than ME-2, and it is also growing in population while ME-2 is not. As a result, the 2020 census found that ME-1 needs to give ME-2 roughly 23,000 additional residents. Democrats control state government in Augusta, but they lack the two-thirds majorities needed to control the redistricting process. So we’re not expecting major changes.

The most straightforward way to address the population imbalance between ME-1 and ME-2 could involve Augusta itself. Kennebec County, home of the quaint state capital, is currently the only county in the state divided between the two districts. It would make sense to just alter the lines within the county to balance the populations, perhaps by switching Augusta itself or the city of Waterville to ME-2. Doing so would reduce ME-2’s Trump percentage, but the changes would be measured more in terms of tenths of a percentage point as opposed to full points. In other words, Golden is still going to be defending a Trump-won district.

One positive thing for Golden is that voters in the district still differentiate among different parties in different races: While Golden was winning by six points last November, Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) won the district by 24 points. But Golden should still be in for a significant test next year.

MARYLAND

Number of seats: 8 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 7-1 D

Current party breakdown: 7-1 D

Most overpopulated district: MD-4 (Eastern Washington, D.C. suburbs)

Most underpopulated district: MD-7 (West Side Baltimore and suburbs)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Democrats

Over the past decade, when Democrats complained about gerrymanders in states like North Carolina and Ohio, Republicans, almost without fail, would point to Maryland — and not without good reason. Maryland, with its wiggly lines and barely contiguous districts, has one of the ugliest congressional maps in the country. After 2010, Democrats held a 6-2 advantage in the state’s delegation. As Maryland was one of the few states Democrats had control over a decade ago, they aimed to expand that advantage. The result was a 7-1 map that was passed by the legislature and signed by then-Gov. Martin O’Malley (D-MD).

The enacted plan worked out as intended for the duration of the decade, although MD-6, the seat that Democrats gained in 2012, nearly reverted back to the GOP in 2014. Still, even partisan Democrats often cringe at the map’s odd shapes. MD-3, for example, was drawn for Rep. John Sarbanes — though it was long a Baltimore-area seat, it takes in a part of Montgomery County, in Washington D.C.’s suburbs, and then juts out to grab the state capital, Annapolis. Sarbanes, whose father was a senator, has been rumored to have statewide ambitions himself. By representing such an odd seat, he’s been able to establish himself in disparate corners of the state — something that would serve him well in a state campaign.

Though Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) remains popular and has worked to establish an independent commission aimed at drawing fair maps, the reality is that Democrats hold veto-proof majorities in the state legislature, thus giving them redistricting power. In a recent U.S. Supreme Court case, plaintiffs alleged that Maryland’s gerrymandered districts violated the First Amendment rights of its voters. The high court declined to intervene in 2019, ruling that federal courts could not constrain partisan gerrymandering. Maryland’s map was left untouched. Though Democratic mappers will have to draw plans that would satisfy the state Court of Appeals — the highest court in the state, where Republican-appointed judges hold a majority — they otherwise have broad latitude. Still, there is a possibility that the state’s high court could intervene on behalf of Republicans much as Democratic-majority state courts have intervened on behalf of Democrats on redistricting matters in North Carolina and Pennsylvania in recent years.

Democrats could try for an 8-0 monopoly in the delegation by targeting Rep. Andy Harris (R, MD-1), who was the sole Republican from the state elected last decade. A member of the Freedom Caucus, Harris is a strident conservative. Earlier this year, dozens of Democratic state legislators accused him of complicity in the Jan. 6 insurrection — though altering his seat may have already been on their minds, this could be a convenient justification for drawing him out. MD-1 has long been characterized as an Eastern Shore district, but it also includes some suburban counties closer to Baltimore — Harris is from Harford County, in the latter category. The suburban Baltimore component is actually the more Republican-leaning part of the district: Trump carried the Eastern Shore 57%-41% while he took over 60% in the rest of the district.

In any case, the Eastern Shore, with 456,000 residents, has enough population for just under 60% of a district. Mappers could take MD-1 across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and bring it into Anne Arundel and Prince George’s counties — it could also feasibly take in some Democratic Baltimore-area precincts. So there are a few ways to draw a Democratic-leaning seat that includes the Eastern Shore. The remainder of the current MD-1 — areas like Harford County — could be split among the adjacent Democratic seats.

By composition, Maryland is about 30% Black, and two of its districts currently have Black majorities. Rep. Anthony Brown’s (D, MD-4) seat is based mainly in Prince George’s County, hugging Washington D.C. MD-4 is 53% Black, and will need to shed about 50,000 people. MD-7, which has a Baltimore focus, is the state’s slowest-growing seat and is just over 50% Black — Baltimore City lost population over the past decade. Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D, MD-7) is on his second congressional tour: He represented the seat from 1987 to 1996, then was replaced by the noteworthy Rep. Elijah Cummings. When Cummings died in 2019, Mfume defeated his successor’s widow to regain the seat. MD-7 will need to pick up about 50,000 residents — to sustain its slim Black majority, it could add some heavily minority precincts. This may make it harder for Democrats to shore up adjacent Reps. John Sarbanes and Dutch Ruppersberger, especially if Democrats also opt to make Harris’s seat bluer.

Though it is possible to draw a third Black-majority seat, MD-5 may soon elect a Black member anyway. MD-5, which pairs a significant chunk of Prince George’s County with southern Maryland, is just over 40% Black and is held by House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D, MD-5) — originally elected in 1981, Hoyer is one of the longest-serving members in state history. In the 2016 Democratic primary for Senate, then-Reps. Chris Van Hollen and Donna Edwards faced off. Though Van Hollen won the primary by 14 points, Edwards, a progressive Black woman, carried MD-5 by a 50%-41% margin. It probably helped that Edwards was from the adjacent MD-4, but it is not hard to see a Black candidate winning an open-seat primary in MD-5. At 82, it seems likely Hoyer will retire sometime over the next few cycles — in his 2020 primary, he received some opposition, though still won with over 60%.

In the Washington D.C. suburbs, Montgomery County, with a population of over a million people, is the state’s largest county. While Sarbanes’ MD-3 has a small part of it, the county is otherwise split between Democratic Reps. David Trone’s MD-6 and Jamie Raskin’s MD-8 — while both districts include some less populous counties, they are both comfortably blue most of the time, although Democrats may want to shore up MD-6, considering their close call in 2014.

Overall, drawing an 8-0 map is probably doable for Democrats, though getting enough incumbents on board, and ensuring that each district is adequately blue, may be tricky. If Democrats opt for another 7-1 plan, it seems likely they’ll simply clean up the current map.

MASSACHUSETTS

Number of seats: 9 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 9-0 D

Current party breakdown: 9-0 D

Most overpopulated district: MA-7 (Boston)

Most underpopulated district: MA-1 (Western Massachusetts)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Democrats

Heavily Democratic Massachusetts is the biggest state in which one of the two major parties is completely shut out of the U.S. House delegation. In fact, Republicans have not won a House election in the Bay State since 1994. Even more strikingly, none of the districts are even particularly close: The closest district based on the 2020 presidential results was the Cape Cod-based MA-9 held by Rep. Bill Keating (D), which Biden still won by nearly 18 points. And all nine districts each gave double-digit margins to the Democratic presidential nominee in 2012, 2016, and 2020. A Republican has not won one of the state’s 14 counties for president since 1988, which helps demonstrate the party’s weakness throughout the state. In 2012, Republicans did come close to beating then-Rep. John Tierney (D, MA-6), who was hurt by his family’s legal problems. But Tierney lost a primary to now-Rep. Seth Moulton (D, MA-6) in 2014, and Moulton has solidified Democratic control of the district.

While Massachusetts does have a Republican governor, Charlie Baker, Democrats hold veto-proof majorities in the state legislature. After having to eliminate a district a decade ago, the legislature’s job is easier this time. Its main job will be adding about 50,000 residents to Western Massachusetts’ MA-1, held by senior Democrat Richard Neal.

The bottom line is that if there is a very competitive House race in Massachusetts in November 2022, something will have gone terribly wrong for Democrats.

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 2-0 D

Current party breakdown: 2-0 D

Most overpopulated district: NH-1 (Manchester/Eastern New Hampshire)

Most underpopulated district: NH-2 (Western New Hampshire)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Split

Landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions in the early 1960s enshrined the concept of “one person, one vote” into congressional redistricting, which created the now-familiar rhythm of redistricting following the release of the decennial census. The first full national redistricting cycle following a census release was in advance of the 1972 election, and there have been full redistricting cycles at the start of every decade since. But prior to those decisions, some states redistricted very infrequently. New Hampshire is an extreme example: The state had the same congressional district lines in place from the early 1880s all the way until the late 1960s.

Still, the lines have only barely changed in recent decades. NH-1 covers some of the eastern part of the state, including Manchester, Portsmouth, and Dover, while NH-2, which has the city of Nashua, covers the rest of the state. In the 1880s, mappers — the state was then controlled by Yankees with GOP loyalties — put Manchester and Nashua in separate districts to dilute the growing white ethnic/Catholic vote, which tended to go Democratic. Today, both districts are winnable by either party under the right circumstances, but Democrats have held the more Democratic western seat (Biden +8.7 in 2020) since 2012 and the more competitive NH-1 since 2016 (Biden +6).

New Hampshire has been the most Republican state at the presidential level in New England for a half-century: The last time any of the region’s six states gave the Republican presidential nominee a better margin than New Hampshire was way back in 1968 — that was Vermont, a traditionally Republican state that has become extremely Democratic at the federal level in recent decades.

That said, New Hampshire has not voted Republican for president since 2000. This Democratic trend is reflected in the state’s delegation to Congress, which is all Democratic (two senators and two House members). But the state’s Republican tradition is alive and well at the state level, as Gov. Chris Sununu (R) won reelection last year in a landslide, aiding a Republican takeover of both chambers of the state legislature. That surprising victory gave Republicans redistricting power in the state.

They now have to consider whether to try to gerrymander NH-1 in such a way to put Rep. Chris Pappas (D, NH-1) in further peril. One way to do this would be to move Manchester into NH-2, strengthening Democrats there, while moving Coos County in northern New Hampshire as well as some Republican-leaning turf in southern New Hampshire into NH-1. This kind of reconfiguration would reduce Biden’s winning margin in the district from half a dozen points to more like one or two points. A more dramatic gerrymander could turn NH-1 into a narrow Trump seat, but one wonders what the appetite would be for such a dramatic transformation of congressional district lines that have not changed much in close to a century and a half.

The other Republican consideration might be this: In a good enough year, Republicans could conceivably win both seats in historically very swingy New Hampshire, but strengthening Republicans in NH-1 would likely move NH-2 out of the range in which it was plausibly winnable for Republicans. Perhaps Granite State Republicans already believe NH-2 isn’t a seat they can compete for anymore, which would be an argument for making NH-1 less Democratic.

NEW JERSEY

Number of seats: 12 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 6-6 Split

Current party breakdown: 10-2 D

Most overpopulated district: NJ-8 (Hoboken/Elizabeth/Part of Newark)

Most underpopulated district: NJ-2 (South Jersey)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Commission

New Jersey is an example of how a district plan that appears to favor one side at the start of the decade can perform contrary to expectations by the end of the decade.

The Garden State uses a commission system in which each party gets six members. Those 12 members then decide on a 13th member to break ties. A decade ago and as New Jersey was losing a district due to slower population growth, the tiebreaker sided with Republicans on the congressional map, and two incumbent Democrats ended up running against each other in North Jersey: Rep. Bill Pascrell (D, NJ-9) prevailed in that primary. The GOP map also modestly reconfigured NJ-3, a swing seat that Republicans had captured in 2010, which had the effect of strengthening Republicans in that seat. In both 2012 and 2014, New Jersey produced a 6-6 congressional delegation in a state that otherwise clearly leans Democratic.

But Republicans held a number of districts in North Jersey that are relatively affluent, suburban/exurban, and highly-educated. They lost one in 2016, when now-Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D, NJ-5) defeated social conservative Scott Garrett (R), and then two more in 2018, when now-Reps. Tom Malinowski (D, NJ-7) and Mikie Sherrill (D, NJ-11) won similar districts. All three of these districts voted for Mitt Romney in 2012 but then flipped to Democratic presidential nominees in 2016 and/or 2020. Meanwhile, in South Jersey, Trump twice won NJ-2 and NJ-3 after Barack Obama carried them in 2012, but that did not prevent Democrats from capturing both seats in 2018. Rep. Andy Kim (D, NJ-3) won a second term last year despite Trump carrying his district by just a couple tenths of a percentage point, while Rep. Jeff Van Drew (R, NJ-2) switched parties during Trump’s first impeachment fight and won a second term last year.

Even at 10-2 — down from an 11-1 high water mark prior to Van Drew’s defection — Democrats still have what is otherwise their largest edge in the New Jersey House delegation since the 1974 election, a huge year for Democrats nationally when Democrats won a 12-3 advantage in the Garden State.

Realistically, protecting this edge under what might be trying electoral circumstances in 2022 would be a significant win for Democrats. They caught a break in the redistricting commission process: The two parties could not come to an agreement on a tiebreaking commission member, so they punted the decision to the state Supreme Court, which selected the Democrats’ preferred tiebreaker. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the Democrats will get to gerrymander, but they may have a better chance of getting their preferred map compared to the Republicans.

Because New Jersey is not adding or subtracting any seats, it may be that there are not huge changes. But there are adjustments that will have to be made because of population. One positive for Democrats is that the two most overpopulated districts, those held by Reps. Albio Sires (D, NJ-8) and Donald M. Payne Jr. (D, NJ-10) in the parts of New Jersey closest to New York City, are also by far the two most Democratic districts in the state. So the swing districts in North Jersey, all of which need to grow to some extent, could hypothetically get strengthened by taking little pieces of the overpopulated New York City-area seats. But the districts could be redrawn in lots of different ways. Based on 2020, the most vulnerable Democrat in the delegation may be Malinowski, even though Biden did better in his district than in any of the others that Democrats picked up in the state in 2016 and 2018. He faces a rematch with state Senate Minority Leader Tom Kean Jr. (R), who nearly beat him last year. Joey Fox of the New Jersey Globe described three different scenarios for re-drawing NJ-7 in which the district hardly changes at all, gets more Democratic by extending further into the New York City area, or gets more Republican by becoming more western-oriented. Whatever happens in NJ-7 could have ripple effects in NJ-5 and NJ-11, too. Under the current map, all three of these districts are winnable for Republicans, but perhaps the changes will make one or more markedly less or more competitive.

Meanwhile, the competitive NJ-2 (held by Van Drew) and NJ-3 (held by Kim) are both underpopulated, so each will need to grow. One possible solution could involve swaps between the districts to shore up both incumbents, although Republicans will still want to compete for NJ-3 and Democrats may still want to target NJ-2, particularly if redistricting made the district bluer. A pro-incumbent scenario would probably have Van Drew take in more of Ocean County, which is the more Republican part of the current NJ-3.

As with many other commission states, we find it difficult to handicap what might happen. Democrats did win the first battle of the fight by getting their preferred tiebreaker, but much else is uncertain. Beyond redistricting, New Jersey is a good state to watch to measure any possible backlash against the Biden White House. A big Republican year would necessarily entail them winning back some highly-educated suburban seats where Trump was relatively weak compared to previous Republicans. Several seats in New Jersey fit that description.

NEW YORK

Number of seats: 26 (-1 from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 21-6 D

Current party breakdown: 19-8 D

Most overpopulated district: NY-12 (East Side Manhattan/Astoria/Greenpoint)

Most underpopulated district: NY-23 (Western New York’s Southern Tier)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Split

Over the past several decades, New York’s congressional reappointment, summed up in the 2000 edition of the Almanac of American Politics, could be described as “carnage.” Since the 1950 census, the state has sent fewer members to the House each decade. In 1952, the first election after the downsizing trend started, the Empire State elected 43 representatives — next year, that number will be down to 26.

For 2020, the bloodletting nearly stopped. To the chagrin of New Yorkers, the Census Bureau announced that, had the state reported just 89 more residents, it would have retained all its seats. Still, at some points during this past decade, the state seemed to be on track to lose two seats, as it did in the 2010 census — so New Yorkers may take some cold comfort in that their losses could have been worse. New York also may not have lost any seats were it not for COVID-19; a recent study by political scientists Jonathan Cervas and Bernard Grofman found that New York was the only state to lose a seat because of deaths early in the pandemic.

Though New York will again be losing representation in Congress, the regime in Albany has changed. Ten years ago, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D-NY) had just won his first term, and he seemed intent on preserving his clean, reformist image — he pledged to veto any congressional map that featured gerrymandered districts. After the Republican-controlled state Senate and the Democratic state Assembly could not agree on a compromise plan, the process was kicked to a three-judge panel, which passed a map. U.S. Magistrate Judge Roanne Mann, who the panel designated to draw the map, seemed to aim for geographic and partisan balance when finding districts to cut. The seat held by Rep. Maurice Hinchey, an Upstate Democrat who was retiring anyway, was eliminated, while Republican Rep. Bob Turner, who won a 2011 special election to the seat previously held by the now-infamous Anthony Weiner (D) and was the delegation’s most junior member, also saw his New York City-area seat vanish.

Despite the deadlocked legislature, one reform that came out of the 2010 round of redistricting was an independent commission, although it would not be in place until 2020. Legislative leaders put language establishing the commission on the November 2014 ballot — it was approved 58%-42%. While the commission includes members of both parties and will draft maps, the legislature is not obligated to follow its recommendations: if the legislature rejects the commission’s plans twice, legislators can amend the maps.

The 2014 constitutional amendment also established standards for passing maps: if control of the legislature is split, a simple majority in each chamber is required to pass maps, but if one party controls both houses (as Democrats do), a two-thirds vote is needed. In November, New Yorkers will vote on another referendum that is aimed at lowering the latter threshold. If Proposal 1 is passed, the Democratic legislature’s two-thirds threshold will be reduced to a simple majority standard. Democrats already have large enough majorities in both chambers to clear the two-thirds threshold, but Proposal 1 would give them more room for defections.

Democrats have controlled the state Assembly since the 1970s, but in 2018, they flipped the state Senate and expanded their majority in 2020. The embattled Cuomo recently resigned, turning the governorship over to Kathy Hochul (D), the now-former lieutenant governor. Hochul is running for a full term next year and faces a potentially competitive primary. Perhaps with that in mind, she has signaled a willingness to play hardball, if necessary, to help Democrats pass favorable maps. Hochul may have other personal reasons for being a team player: She knows firsthand what it’s like to come up on the short end of the redistricting process. In 2011, she won a special election for a Republican-leaning seat that spanned from Buffalo to Rochester. The plan that the three-judge panel enacted did not help her — running for reelection in a similar seat the next year, she lost 51%-49%, though she still ran more than 10 points ahead of Barack Obama’s showing in the district.

So, if Hochul and the Democratic legislature get their way, what would their map look like?

Starting on Long Island, four-term Rep. Lee Zeldin (R, NY-1) is running for governor and is leaving behind an open seat that is entirely within Suffolk County. Next door, first-term Republican Rep. Andrew Garbarino’s NY-2 is also based mostly in Suffolk County, though it also contains part of Nassau County. As drawn, Trump carried both districts by about four points last year — in congressional races, Democrats have watched heralded candidates come up short in those districts over recent cycles. Democrats’ solution may be to concede one while making the other more winnable. Moving the cities of Brentwood and Wyandanch into NY-1 would turn it into a slightly Democratic-leaning seat while NY-2, which already includes a red part of Nassau County, could take in Republican parts of NY-1.

Moving west, Rep. Tom Suozzi’s (D, NY-3) district takes in parts of northern Suffolk and Nassau counties, but will probably expand its holdings in Democratic areas of Queens. Rep. Kathleen Rice’s (D, NY-4) seat is entirely confined to Nassau County, and that could still be the case next year. Democrats could shore her up by moving some minority-heavy precincts in western Nassau from NY-5 into NY-4. As drawn, both NY-3 and NY-4 gave Biden about 55% — a clear majority, but in the event of a bad year, Democrats would probably want to increase that number.

Currently, New York City includes all or parts of 13 districts. Democrats hold all of those districts except for NY-11, which they will almost certainly look to flip. Democrats held that district from 2018 to 2020, but the seat fell back into Republican hands last year when then-state Assemblywoman Nicole Malliotakis beat then-Rep. Max Rose (D, NY-11) by six points. NY-11 is mostly based in Staten Island, which has enough population for about 65% of a district, and usually leans Republican (Malliotakis carried it 55%-45%). On the current plan, the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge connects Staten Island to some neighborhoods in Brooklyn, such as Fort Hamilton and Gravesend — the Brooklyn part of NY-11 is Democratic, but not overwhelmingly so, as it supported Rose 52%-48%. Assuming mappers keep Staten Island whole, Democrats could turn NY-11 into a Biden district (Trump carried the current version by just over 10 points) by giving it different areas of Brooklyn, or perhaps even bringing it into Manhattan (this was the case on some previous plans).

There is little question that the other 12 districts in New York City will remain Democratic, so other considerations, such as racial demographics, will inform the line-drawing more than anything else — as the Crystal Ball showed a few months ago, when we previewed the mayoral primary, NYC is certainly a diverse city. In Queens, for example, Rep. Grace Meng (D, NY-6) holds the most heavily Asian district on the Eastern Seaboard. Her NY-6 is currently about 45% Asian, but could possibly become Asian-majority.

Democratic incumbents will also have personal preferences. Veteran Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D, NY-12) has had some competitive primaries over the last few cycles: she has a base in Manhattan but, in primaries, has polled poorly in the gentrifying parts of Kings and Queens that are in her district. Maloney may be reluctant to take on much more territory from the latter. Maloney’s geographic situation is ironic when considering how she ended up in Congress. She was first elected in 1992, beating moderate Republican Rep. Bill Green: Green narrowly carried Manhattan, where the bulk of the district was located, but Maloney won by taking over 60% between its Kings and Queens portions.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D, NY-10) also has a sizable portion of Manhattan, but his district reaches down into Brooklyn to include some heavily Orthodox Jewish precincts. As an aside, because of Orthodox Jews and other conservative constituencies, it is possible to draw a Republican-leaning seat in Brooklyn, but Democrats will probably ensure GOP strength there remains diluted. It is possible that either, or both, of Maloney or Nadler may retire — they were both originally elected in 1992 and will each be 75 or older by Election Day 2022 — which could make things easier on mappers.

Moving north of the city, some big changes are likely in store for Upstate New York: currently, five of the eight Republicans in the state’s delegation are from there. On an effective Democratic gerrymander, Republicans could be reduced to just two Upstate seats.

Reps. Elise Stefanik (R, NY-21) and Claudia Tenney (R, NY-22) both ran as allies of former President Trump and hold adjacent seats. Stefanik’s district takes in the North Country and overlaps with Adirondack National Park. Politically, the area that makes up the current NY-21 votes like many blue collar pockets of the Midwest: after giving Obama modest majorities, it supported Trump by double-digits. Tenney was first elected in 2016 to a seat just to the south, which includes Utica and Oneida. Two years later, Tenney lost 51%-49% to Democratic state Assemblyman Anthony Brindisi — however, in an agonizing result for Democrats, Brindisi lost a 2020 rematch by 109 votes.

Though Democratic partisans would very much like to defeat both Upstate Republican women, from a practical standpoint, they would probably be better off giving one a safe seat — that way, adjacent seats would be more Democratic. It would not be hard to build a safely red seat around the Mohawk Valley, an area that Stefanik and Tenney each currently represent parts of. One source of Democratic votes in NY-21 is Clinton County (Plattsburgh), in the district’s northeastern corner. Rep. Anthony Delgado’s (D, NY-19) Hudson Valley-area seat could reach up to grab Clinton County, although the area is not as blue as it used to be: while Obama carried Clinton County twice by about 25 points, it has gone Democratic by only single digits in presidential races since. Democrats likely also will try to shore up Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Chairman Sean Patrick Maloney (D, NY-18), who holds a Trump/Biden district south of Delgado’s turf.

Aside from drawing a red seat encompassing the Mohawk Valley, Democrats will likely draw a safely Republican seat in western New York. This could be accomplished by combining the reddest parts of the current NY-23 (the Southern Tier) and NY-27 (the Buffalo-to-Rochester district that is the descendant of Hochul’s old seat). As Rep. Tom Reed (R, NY-23) is retiring, Rep. Chris Jacobs (R, NY-27) would probably be favored for this seat.

With two solidly Republican Upstate seats out of the way, Democrats will look to monopolize the rest of the region — and the lines could be creative, to say the least. In the Albany area, Rep. Paul Tonko (D, NY-20) may be the Upstate Democrat who sees the fewest substantive changes to his district: his seat will likely remain anchored in the state’s capital city — while it is not as blue as the NYC districts, it should be out of reach for Republicans (the current version supported Biden by 21%).

In western New York, Rep. Brian Higgins (D, NY-26) currently holds a district that contains all of Buffalo. His district could easily take in more surrounding precincts in Erie County, as Democrats unpack it somewhat. Higgins’ current district gave Biden a 27-point margin, and he himself is one of Congress’ lower-profile electoral overperformers. It seems likely that mappers will take excess Democrats from Buffalo and, using Niagara and Orleans counties as a bridge, connect them to Democrats in the Rochester area — in the first decade of the 2000s, the late Rep. Louise Slaughter (D) represented a seat with a similar configuration. Rep. Joe Morelle (D, NY-25), who replaced Slaughter after her 2018 death, could run in that seat.

After recreating the Slaughter seat, Democrats will probably still have some blue turf left over in Rochester’s Monroe County. This area could be put into Republican Rep. John Katko’s Syracuse-area district. Katko was initially elected in 2014, and, to the frustration of Democrats, this moderate Republican has remained popular in his blue seat. It is possible that, with enough new (and Democratic-leaning) constituents, Katko would be more vulnerable in a general election or primary (Katko voted for the second impeachment of Donald Trump, drawing the former president’s ire). For good measure, it’s easy to see Democrats cracking Syracuse’s Onondaga County.

The part of Onondaga County that doesn’t end up with Rochester could be put with other smaller Upstate metros. Tompkins County, which includes Ithaca (Cornell University), is the bluest Upstate county — in fact, speaking to Biden’s gains with college whites and Trump’s improvement with minorities, 2020 was the first time ever that Tompkins County was more Democratic than Queens. Tompkins County is currently in the GOP-leaning NY-23, so it will almost certainly be removed. A district that includes Tompkins County and part of Onondaga County could grab some blue precincts in Utica.

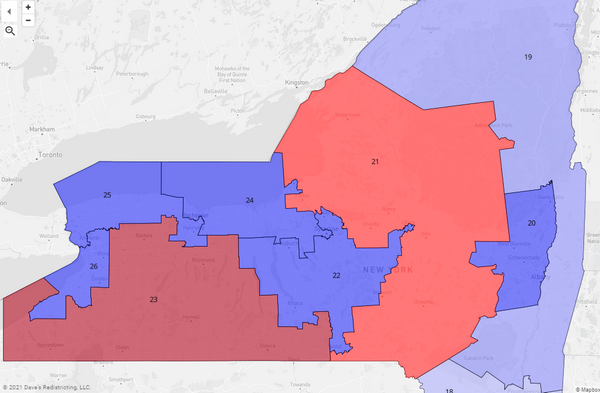

Map 2 illustrates a possible pro-Democratic gerrymander of Upstate New York. Two districts, NY-21 and NY-23, are deeply red, while a stretch of four blue districts span from Buffalo to Utica. Rep. Tonko keeps an Albany-based seat while Delgado’s NY-19 reaches up to Plattsburgh. Districts in Map 2 are colored by their 2012-2016 presidential average: districts 22, 24, 25, and 26 are all about 56% Democratic.

Map 2: Hypothetical Upstate New York Democratic gerrymander

So it’s likely that, assuming they reject any commission-drawn maps, legislative Democrats will end up splitting many large Upstate cities: Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse are all whole on the current map, but partisan mappers will almost certainly want to spread out their Democratic voters.

If everything falls into place for Democrats — something that is not guaranteed — they could expand their current 19-8 edge in the delegation to 23-3. Given their relatively weak hand in other regions of the country, if the battle for the House is truly close, that type of windfall in New York could feasibly save their slim majority.

RHODE ISLAND

Number of seats: 2 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 2-0 D

Current party breakdown: 2-0 D

Most overpopulated district: RI-1 (Most of Providence/eastern Rhode Island)

Most underpopulated district: RI-2 (Western Rhode Island)

Who controls redistricting: Democrats

2012 control: Democrats

Rhode Island was on the bubble in the 2020 reapportionment, and it surprisingly ended up keeping its second seat. Whether Rhode Island lost a seat or kept it, the analysis was going to be pretty straightforward either way: Democrats either would hold two safe seats in the state, or they would hold one.

The Ocean State’s two districts divide the state into western and eastern halves, and each contains part of the state’s largest city and capital, Providence. The eastern part is geographically smaller and runs down to Newport, the seaside tourist destination that is also home to the Naval War College. The western RI-2 contains most of the state’s land mass and is less diverse. Donald Trump came within about seven points of winning RI-2 in 2016, though he lost the district by close to double that in 2020, and Rep. Jim Langevin (D, RI-2) was not seriously challenged even in 2016. RI-1 backed Biden by nearly 30 points last year.

If it was an open seat and if aided by other circumstances, Republicans could hypothetically compete for RI-2, so perhaps Democrats will want to shore up the district to some degree. But Democrats also could just make very minimal changes, as RI-1 only has to shed roughly 5,000 residents to RI-2.

VIRGINIA

Number of seats: 11 (no change from 2010s)

Breakdown in 2012: 8-3 R

Current party breakdown: 7-4 D

Most overpopulated district: VA-10 (Northern Virginia: Leesburg/McLean/Manassas)

Most underpopulated district: VA-9 (Western Virginia)

Who controls redistricting: Commission

2012 control: Republicans

Virginia, which includes the former capital of the Confederacy and has long been identified as a pillar of the Old South, now stands apart from the nation’s historically most conservative region. It has become so much of an outlier that we grouped it not with the South in this series, but rather with the Mid-Atlantic/Northeastern states.

The Old Dominion was the only Southern state that Hillary Clinton won in 2016, and one of only two Joe Biden won in 2020 (Georgia was the other). Democrats control only two state legislative chambers in the entire South: the two in Virginia, although the state House of Delegates is on the ballot this fall, along with the state’s three state-level statewide elected offices (governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general, all of which the Democrats also hold). Virginia is also the only Southern state that now has a commission system for redistricting: Voters approved it in a statewide vote last year after the legislature put it on the ballot.

Without this new system, Democrats would control the levers of redistricting in the state and could strengthen and even expand their 7-4 edge in the state’s congressional delegation. As it stands now, it is unclear who may come out ahead, but Republicans could conceivably re-take a majority in the state’s congressional delegation next year.

A decade ago, Republicans held gerrymandering power in Virginia, and they drew a map that resulted in an 8-3 Republican delegation in both 2012 and 2014. But a racial redistricting lawsuit forced the unpacking of Rep. Bobby Scott’s (D, VA-3) then-majority-Black district. That change transformed Scott’s Richmond-to-Norfolk district into one centered just on the Hampton Roads area, freeing Richmond and other Democratic areas to be put into VA-4, which now-Rep. Don McEachin (D) easily won. The changes also weakened Republican performance in VA-7, which contains western parts of the Richmond area and extends into Central Virginia. Conversely, the new map strengthened Republicans in VA-2, which covers Virginia Beach and other parts of Hampton Roads. Democrats ended up winning and holding both VA-2 and VA-7 in 2018 and 2020 — it seems likely that they would have come up short in VA-7 without the changes.

So the 2016 remap contributed to Democrats winning two additional seats, and they flipped VA-2 even though redistricting made the district less Democratic. The pre-2016 remap was only partial, and Democrats won the unchanged VA-10 in 2018, a highly-educated Northern Virginia suburban seat that has shifted so heavily against Republicans that it isn’t really a swing seat anymore: Mitt Romney won it by a point in 2012; eight years later, Trump lost it by 19.

As of now, Democrats control seven seats and Republicans control four. The Democrats hold four seats in the combined Richmond/Hampton Roads area, and they hold the three dedicated Northern Virginia seats. Republicans hold three districts in Western/Central Virginia — an area our former colleague Geoffrey Skelley once described as “RoVa,” as in the Rest of Virginia outside of Northern Virginia/Greater Richmond/Hampton Roads — and one district, VA-1, that extends from the southern portions of Northern Virginia’s fast-growing Prince William County all the way down to the fringes of Colonial Williamsburg. That district has become more competitive recently, as Trump only won it by about 4.5 points, although Rep. Rob Wittman (R) ran way ahead of Trump.

The commission, composed of a bipartisan group of state legislators and citizens, is off to a rocky start, to the point where some — particularly Democrats — worry that the commission process, which also involves getting approval from the state legislature, will fail. If that happens, it will be up to the conservative state Supreme Court to draw the maps (the justices on that court are appointed by the state legislature, which has been mostly dominated by Republicans for the past couple of decades). The commission did recently agree to try to start from scratch on creating new maps as opposed to using the current districts as a template. One could interpret this as a positive for Democrats, given that the current congressional map was drawn, at least in part, by Republicans. However, as noted above, that gerrymander was altered in important ways already.

It’s also hard to really “start from scratch” on a redistricting map. For instance, the current Democratic-held VA-3 and VA-4 are substantially Black (though neither are currently majority-Black). Significantly strengthening or weakening the Black population in those districts could spur litigation. Additionally, the “Fighting Ninth” district has been based in the southwestern corner of the state since Reconstruction. VA-9 needs to add population and is surrounded on three sides by other states: it will need to expand further east, it’s simply a question of where. VA-9 is bordered to the east by VA-6, a heavily Republican district that contains the Democratic city of Roanoke and the heavily Republican Shenandoah Valley, and VA-5, a Republican-leaning central/southern Virginia seat that has recently hosted some competitive races. Those districts are also underpopulated, so the next versions of each will have to move further north and/or east.

The Northern Virginia districts are all overpopulated and will need to contract to some degree. VA-2 in Hampton Roads, held by Rep. Elaine Luria (D), is underpopulated, and it is hard to reconfigure the district as anything other than a swing seat, particularly given the likelihood that neighboring VA-3 and VA-4 aren’t likely to change much. About 60% of VA-2 comes from Virginia Beach, a Trump-to-Biden locality that has usually voted roughly five percentage points more Republican than Virginia as a whole in recent statewide races. VA-7, the Greater Richmond/central Virginia seat held by Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D), could be made either more or less Democratic. If Democrats were in charge of the process, they might have followed Interstate 64 to link the Richmond part of VA-7 with Democratic Charlottesville/Albemarle County — this would produce a blue-leaning seat. An iteration of this seat is possible, but Republicans will likely fight against it. VA-5, which currently covers Charlottesville, would become safely Republican if the city was moved into another district, but the district also could be reconfigured in such a way that it would remain competitive under the right circumstances.

With a first-time commission process unfolding that potentially has a conservative-leaning backstop in the Supreme Court of Virginia, this is a hard process to handicap. Democrats likely will come out of this process with three safe seats in Northern Virginia and two in Richmond/Hampton Roads. Republicans should come out of it able to at least defend the four seats they hold now, although the trajectory of VA-1 and whether it becomes a swing seat, either through redistricting now or political changes later, will merit monitoring. Then it’s just a question of how the state’s two most competitive seats, Democratic-held VA-2 and VA-7, end up looking. If both remain marginal, Republicans should seriously be able to contest both, and redistricting could make their job easier in one or both seats.

If Republicans are able to hold what they currently have and flip VA-2 and VA-7, Virginia will regain a commonality it recently shared with the rest of the classically-defined South: a Republican majority in its congressional delegation.

Conclusion

Clearly, New York is by far the most important state in this group in terms of national House control. An aggressive Democratic gerrymander, if Democrats can pull it off, could help make up for Republican gerrymandering elsewhere. We don’t expect huge shifts based on redistricting in the region’s other states, although there are consequential choices to be made in several of them.

We’ve now looked at all 44 states that have more than one congressional district. Next week, we’re going to summarize what we’ve written and offer an overall assessment of the redistricting picture as the remapping process begins in earnest following Labor Day.