| Dear Readers: This is the third part of our multi-part series on congressional redistricting. Part One provided a national overview, and Part Two covered several small-to-medium-sized states in the Greater South. This week, we’re analyzing four big Southern states – Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas – which, together, represent a potential gerrymandering bonanza for Republicans.

We will cover additional regions in the coming weeks. — The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Democrats tried but failed to get a seat at the redistricting table in four large Southern states in the 2018 and 2020 cycles: Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas.

— The consequences for redistricting are vitally important. It’s easy to imagine Republicans squeezing a half-dozen extra seats out of just these four states in 2022, and that may be just a floor on their potential gains.

— However, Republicans could also overreach, and court battles appear likely in all of these states.

Redistricting in the big-state South

The late 2010s featured a number of near-misses for Democrats to get a seat at the table in redistricting in four, large states that lean Republican but are or are getting more competitive. In 2018, Democrats lost the Florida and Georgia gubernatorial races by 0.4 and 1.4 points, respectively. Had they won those races, Democratic governors could have used their veto power in those states to block Republican gerrymanders.

Democrats also heavily prioritized flipping state legislative chambers in North Carolina and Texas last year, but came up well short of doing so.

So Democrats are now fearful, and Republicans are hopeful, that the GOP can squeeze even more seats out of these four growing states. The Democrats’ worries were spelled out last week in the liberal publication Mother Jones, which reported data from the Democratic firm TargetSmart arguing that Republicans could net anywhere from 6-13 seats just from gerrymandering these states alone. The National Democratic Redistricting Committee pegs the potential Republican gains in these states as possibly even higher: 11-16 seats.

Now, some of this might be just “sky is falling” rhetoric from Democrats who are trying to shock Democratic senators into doing away with the filibuster and pushing through the party’s “For the People Act,” which would mandate independent redistricting commissions in every state (the Democratic-controlled House has already approved the bill). But there’s also no question that Republicans are going to try to sharpen their already-impressive congressional margins in these four growing states, and it’s easy to imagine them reaching at least the floor of the Democrats’ pessimistic projections (netting six seats), and quite possibly gaining more than that. In other words, the sky might actually be falling for Democrats in these states.

As of right now, these four states, combined, have 90 of the 435 House seats, and Republicans currently hold 55 of these seats, or 61.1% of the total. That’s a markedly better share of the seats than the region’s presidential vote from 2020 might indicate: Donald Trump won 51.6% of the two-party presidential vote in these four states, combined. Florida and North Carolina, two states that Barack Obama won at least once, have remained stubbornly right of center. Georgia and Texas are trending Democratic relative to the nation, but are also right of center (Texas more so than Georgia, which Joe Biden narrowly carried in 2020).

Texas will be adding two seats, going from 36 to 38, while Florida and North Carolina will be adding a seat apiece, going from 27 to 28 and 13 to 14, respectively. Georgia, which added a 14th seat last decade, is the only one of these four that won’t add a seat this decade. That will push this quartet’s total to 94 seats, meaning that they will have one-fifth (22%) of all the nation’s House seats.

Let’s take a closer look at redistricting in these four key states and assess how good it might get for Republicans, and how bad it might get for Democrats.

FLORIDA

Number of seats: 28 (up 1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 17-10 R

Current party breakdown: 16-11 R

Most overpopulated district: FL-9 (Central Florida)

Most underpopulated district: FL-2 (Panhandle)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

In Florida, the coming redistricting process should bring no shortage of heartache for Democrats, but one of their most critical letdowns occurred almost three years ago: the winner of the 2018 gubernatorial race would get the opportunity to fill three seats on the state Supreme Court, as three Democratic-appointed justices were set to retire (judges on that court face a mandatory retirement age). In 2015, the state Supreme Court forced changes to the state’s Republican-drawn congressional map. The new map precipitated several Democrats pick-ups in the 2016 and 2018 cycles.

Despite trailing in most polls, and running in an unfavorable national environment, then-Rep. Ron DeSantis (R, FL-6) upset then-Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum (D) to keep the governor’s mansion in Republican hands. DeSantis filled the three positions, and the Florida Supreme Court is now one of the most conservative state courts in the country. With a new jurisprudence dominating the court, Democrats will find a less sympathetic audience for any redistricting challenges, though Republican legislators may not want to get too creative for their own good. Republican mappers may also be limited by the Fair Districts Amendment, a ballot measure that passed in 2010 and was meant to encourage compact and fair districts (but which Democrats are fearful that this court effectively will not enforce after the more liberal version of the court used it against GOP gerrymanders last decade).

With all this out of the way, let’s consider where things stand now, and what’s likely to change.

After the 2014 election, Republicans retained a 17-10 edge in the state’s delegation. But by the end of 2018, with a new map and a favorable midterm environment, Democrats had clawed within one seat of majority in the delegation, which became 14-13 Republican. Then, in 2020, as former President Donald Trump carried Florida by more than three percentage points — a comfortable margin, by state standards — he helped Republicans regain two seats in the Miami area, bringing their advantage back up to 16-11. The delegation will grow by one member at the start of the next Congress, although most observers expected it to gain two — Florida has added members since the 1940 census, when it was the least populous state in the South. It is now the nation’s third most populous state, trailing only California and Texas.

The most underpopulated district in the state in the panhandle-based FL-2, held by Republican Rep. Neal Dunn. The 2nd District, which is now mostly rural, traditionally included the city of Tallahassee. But with the 2015 remap, most of the 2nd’s holdings in the city were given to the newly drawn FL-5, which was intended to be a majority-nonwhite seat. While Rep. Al Lawson (D, FL-5) hails from the state’s capital area and represented in the legislature for years before his 2016 election to congress, a greater portion of the district actually comes from Jacksonville (it includes most of the city’s Black precincts). While some Republicans have maintained that the current iteration of FL-5 is not protected by the Voting Rights Act — by composition, it is less than 50% Black — Nicholas Warren of the Florida ACLU, argues that major changes won’t be in store for the district. We will just have to wait and see how Republicans deal with this district, and what legal fallout may ensue.

Moving south to the Orlando area, Democrats hold three seats, but seem likely to come out of redistricting with only two. FL-10, which is split roughly evenly among whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, was a seat created for 2015, and seems unlikely to change — as it usually gives Democrats over 60% of the vote, it acts as a vote sink in the area. Just to the south, the most populous district in the state is Rep. Darren Soto’s (D) FL-9, which needs to drop a whopping 165,000 residents. Whites and Hispanics each account for roughly 40% of the 9th’s population, though the latter group’s growth has been especially rapid. Given its minority population, Republicans may also steer clear of drastically reshaping FL-9 — it currently has a mild Democratic lean, but its redder holdings could be transferred out to shore up adjacent GOP seats.

North of Orlando, Republicans will likely target Rep. Stephanie Murphy’s (D, FL-7) district — though it contains some of Orlando proper, suburban Seminole County makes up the majority of FL-7. Unlike districts 9 and 10, the 7th has a white majority. Though the trends for Republicans in Seminole County have not been good (it was a Trump-to-Biden county), legislators could make it redder by giving it parts of working-class Volusia County, or rural precincts of Lake County. If FL-7 is heavily altered, Murphy, who is a leader in the moderate Blue Dog Coalition, may be able to run in a new version of FL-10, as Rep. Val Demings (D, FL-10) is running for Senate (though other credible Democratic candidates have already announced bids for the open seat).

Over in the Tampa Bay area, FL-13, which takes up three-quarters of Pinellas County, is another Blue Dog district that Republicans will have their eye on. Former Gov. Charlie Crist — who has, under three partisan labels, been a fixture in state politics for the last quarter-century — won this seat in 2016, but is now running for his old job. Before 2016, the legislature grouped most of the heavily Black precincts in St. Petersburg, Crist’s hometown, into Rep. Kathy Castor’s safely blue FL-14, which was focused on downtown Tampa (both parts of the district touched Tampa Bay, so the seat was contiguous). When the entirety of St. Petersburg was put back into FL-13, Crist ran and beat then-Rep. David Jolly (R) 52%-48% — those precincts were decisive.

With a friendly court, Republicans may try to put parts of St. Petersburg back into FL-14, though Democrats would probably cite the Fair Districts Amendment and sue. If Republicans wanted to go a less risky route, FL-13 is one of the few districts in the state that needs to gain population — they could simply add some redder Pinellas County precincts that are currently in FL-12. This district is competitive enough already that a Republican might be able to win it as its currently drawn, and Republicans may very well attempt to make it redder.

Finally, in south Florida, Republicans will probably be more interested in shoring up their current members than targeting Democrats. In 2020, three Cuban-American Republicans were elected to represent the Miami area: veteran Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R, FL-25) was unopposed for a 10th term, while now-Reps. Carlos Gimenez (R, FL-26) and Maria Elvira Salazar (R, FL-27) ousted Democratic incumbents who were first elected in 2018. Salazar is the only one of the trio who holds a Biden seat, though the president’s three-point margin in her district was down considerably from Hillary Clinton’s 20% margin from 2016. Republicans may remove parts of Miami Beach, which has a sizeable white liberal bloc, and give Salazar more ethnically Cuban precincts that are currently in Diaz-Balart’s seat. Gimenez may also want some help — though Trump carried his FL-26 by six points, it gave Clinton 57%.

If Trump’s numbers with Cubans represent a new normal, the GOP’s Miami-area incumbents should have little to fear. But Republican legislators would be wise to draw the lines with the understanding that this may not be the case.

Ultimately, Florida, like the other states mentioned here, is a state where Republicans likely will go as far as courts let them — or as far as they think courts will let them.

GEORGIA

Number of seats: 14 (no change from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 9-5 R

Current party breakdown: 8-6 R

Most overpopulated district: GA-7 (Greater Atlanta)

Most underpopulated district: GA-2 (Southwest Georgia)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

Georgia has been at the forefront of national politics over the last year. After hosting a razor-thin presidential contest and two blockbuster Senate runoff elections, the Peach State will once again find itself in the national spotlight when maps are redrawn later this year.

Though Democrats have found success in recent statewide elections, Republicans will be overseeing the mapmaking process because they still have majorities in both chambers of the state legislature and hold the governorship. With that trifecta, Republicans will face a tough balancing act: they will want to stymie Democratic gains in the Atlanta area but also protect their own incumbents — all while keeping the Voting Rights Act in mind.

To understand the daunting task that Georgia Republicans face, we must take a trip back in time to the early 2000s. Back then, Democrats had dominated state government since Reconstruction, but they faced an increasingly competitive GOP. Republicans were beginning to post impressive numbers in the state’s rural areas and cut into the Democrats’ state legislative majorities.

Democrats, seeing the writing on the wall, concocted egregious congressional and state legislative gerrymanders to preserve their dwindling grip on power.

The congressional map was certainly not easy on the eyes. The 2002 Almanac of American Politics noted that the map must be “admired for its creativity.” The state was awarded two new seats in the 2000 census, and, not coincidentally, both were drawn to favor Democrats. Still, the Almanac authors warned that the map may not last the entire decade, citing not only Republicans’ rise to power but several federal lawsuits challenging the legality of the maps. “This work of art may not endure,” the Almanac noted.

Sure enough, they were right. Courts threw out the Democrats’ state legislative maps, paving the way for Republicans to grab control of state government for the first time since Reconstruction. One of their first orders of business was redrawing the congressional map in a rare mid-decade redistricting session. The new map was much more compact and split fewer counties than its predecessor. Republicans also attempted to make more life more difficult for then-Reps. John Barrow (D, GA-12) and Jim Marshall (D, GA-8), two white Democrats with moderate voting records. Despite facing tougher constituencies, both Democrats were narrowly reelected in 2006’s broader Democratic wave.

In 2010, Rep. Sanford Bishop (D, GA-2), in the southwest, faced a surprisingly close race — so close that some news networks called it for his Republican opponent on Election Night. Elsewhere, Marshall lost reelection to now-Rep. Austin Scott (R, GA-8), but Barrow was comfortably reelected.

In the 2011 redistricting session, Republicans decided to make a tradeoff in order to protect Scott: Bibb County, which includes Macon, was the anchor of Scott’s district. GOP mapmakers decided to cede Bibb to Bishop in exchange for adding more rural counties to the 8th — importantly, as we’ll see later, this pushed the Black population share in GA-2 to over 50%. They also had their sights set on Barrow once again: they removed Savannah from his district and added more rural counties such as Coffee and Jeff Davis. When Barrow lost in 2014, he was the only remaining white Democrat in the Deep South — with his loss, the map produced its intended 10-4 Republican split.

This brings us to the upcoming redistricting process. Recent Democratic gains in the metro Atlanta suburbs have shifted the delegation from 10-4 to 8-6 Republican. In the 6th District, Rep. Lucy McBath (D) pulled off one of the biggest upsets of the 2018 midterms when she ousted Rep. Karen Handel (R), who had just won a high-dollar special election for this suburban district the previous year. The 6th also saw one of the largest swings from Barack Obama in 2012 to Joe Biden in 2020 of any district in the nation, going from Obama -23 to Biden+11. Handel waged a rematch in 2020, which McBath won comfortably.

In the 7th District, which includes most of rapidly diversifying Gwinnett County, now-Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux (D) came within 500 votes of ousting Rep. Rob Woodall (R) in what was the single closest House race of the entire 2018 campaign. Woodall decided against running for reelection in 2020, and Bourdeaux narrowly defeated emergency room physician Rich McCormick (R) in the general election, making her the only Democrat to flip a competitive Republican-held district in 2020.

Republicans are going to have to address their recent decline across the metro Atlanta suburbs, where they still have plenty of room to fall. No one knows what the map will end up looking like, but the general consensus seems to be that Republicans will attempt to combine the bluest parts of the 6th and 7th districts into one safely Democratic vote sink, in exchange for creating a new solidly Republican seat in rural and exurban northeast Georgia.

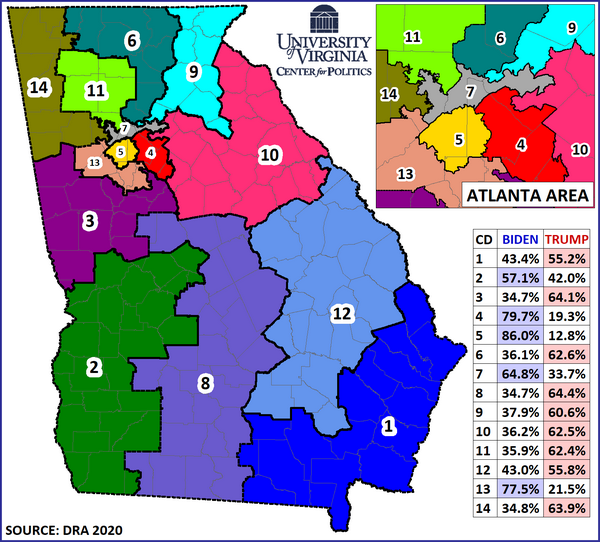

On Map 1, GA-7, a checkmark-shaped district arching across the Atlanta metro, would have given Biden a 30-point margin, while the much redder 6th District is stretched up to the northern border.

Map 1: Hypothetical 9-5 Republican Georgia gerrymander

The result of Map 1 would very likely be a Georgia delegation with nine Republicans and five Democrats. If GOP legislators try to redraw a Democratic-held seat to elect a Republican (GA-6, in this case), some of their own members, especially Reps. Andrew Clyde (R, GA-9) and Marjorie Taylor Greene (R, GA-14), would have to be team players: currently, both of their seats gave Trump about 75% of the vote, but are knocked down to under 65% Trump in Map 1. At the same time, Republicans would want to strengthen Rep. Barry Loudermilk (R, GA-11) — over the last decade, his district has crept down from 67% Romney in 2012 to 57% for Trump. On Map 1, GA-11 drops some of its closer-in parts of the Atlanta metro, and Trump’s share climbs back to 63%.

So if Republicans spread themselves out efficiently, most of their districts would end up being between 60% and 65% Trump — this is the case for seven of their nine seats on Map 1. Districts 1 and 12 are each closer to 55% Trump, but both are racially polarized and outside of their urban centers (Savannah and Augusta, respectively), Democratic support drops off steeply.

GA-7’s unique demographic trajectory may be one reason why Republicans may preserve it as a Democratic-leaning seat: it was originally drawn to be about 50% white but is now firmly a majority-nonwhite seat, so big changes could be seen as a violation of the Voting Rights Act by Democratic redistricting lawyers. Still, a judge may also note that Section 2 of the VRA mandates that some districts be drawn so that certain minority groups can elect candidates of their choice. Though the 7th District is now majority-minority, Bourdeaux herself is white, and the district also includes a mix of different types of voters of color (the district is roughly two-fifths white, a fifth Black, a fifth Hispanic, and a sixth Asian). We asked Charles Bullock, a redistricting expert at the University of Georgia who recently released a second edition of his excellent book, Redistricting: The Most Political Activity in America, about the 7th District. He noted that plaintiffs in a lawsuit based on the VRA’s Section 2 would face the challenge of showing that members of the three non-Hispanic white ethnic groups vote alike.

Some Republicans have also suggested that Bishop’s GA-2 might be at risk — the version on Map 1 gave Biden a not-overwhelming 57%, and it could easily be made more Republican. Carving out a redder district in southwest Georgia may seem enticing for the GOP, but a move like this could be seen as a violation of the Voting Rights Act. Unlike the 7th, the 2nd was intended to be a majority-minority district (remember, Republicans did this on purpose a decade ago in order to shore up the then-newly-elected Scott next door in GA-8). Black voters in the 2nd may feel disenfranchised if they are unable to have appropriate representation in Congress. Plus, it’s not guaranteed that a more competitive district in Southwest Georgia would be completely unwinnable for Bishop. His moderate stances on abortion and gun rights have played well with rural white voters over the years. And while we may live in era where down-ticket races are becoming increasingly tied to presidential races, Bishop maintains a respectable amount of crossover support. Bullock agreed that the district might be redrawn in such a way that Bishop could hold it, but perhaps not another Democrat if Bishop retired at some point this decade (Bishop is 74).

To make a long story short, Republicans are now facing the same predicament that Democrats faced two decades ago. Their majorities in the state legislature are getting smaller, the minority party has been surprisingly successful in recent statewide elections, and they are facing a grim outlook in areas of the state where they once dominated. Republicans are aware that redistricting could be their last chance to forestall new Democratic gains in state government.

NORTH CAROLINA

Number of seats: 14 (+1 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 9-4 R

Current party breakdown: 8-5 R

Most overpopulated district: NC-12 (Charlotte)

Most underpopulated district: NC-1 (Northeast North Carolina)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

Tar Heel State Republicans drew two effective gerrymanders in the 2010s. The first one, which was in effect for the 2012 and 2014 elections, aimed to reverse a Democratic gerrymander from the 2000s, which helped Democrats maintain a narrow 7-6 advantage in the state even in the 2010 Republican wave. Republicans immediately won a 9-4 edge in 2012, and they got to their goal of 10-3 by 2014. But then a federal court threw out that map for packing too many minority voters into too few districts. So Republicans went back to the drawing board and drew another 10-3 map; as part of that, they unwound the serpentine and heavily litigated NC-12, a majority-minority district that took in Black pockets in Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and Charlotte. That district is now entirely contained within Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County.

State courts, led by a Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court, unwound the congressional map once again during the 2020 cycle, which forced North Carolina Republicans to make some actual concessions. So they drew two new safe Democratic seats, one in Winston-Salem/Greensboro/High Point and the other in the Raleigh area, and the state elected an 8-5 Republican delegation.

Republicans kept control of the state House and Senate last year, and while North Carolina has a Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, he has no role in redistricting and cannot veto maps. Democrats do still have control of the state Supreme Court, although a rough 2020 cycle cut their 6-1 edge to 4-3. Democrats hope that the precedent from the recent state court decisions that reconfigured the past map could constrain Republican gerrymandering. Republicans hope to grab the majority on the court in the 2022 election, and their narrow victory in the race for the court’s chief justice position last year might also provide them some logistical advantages in a Democratic lawsuit over gerrymandering.

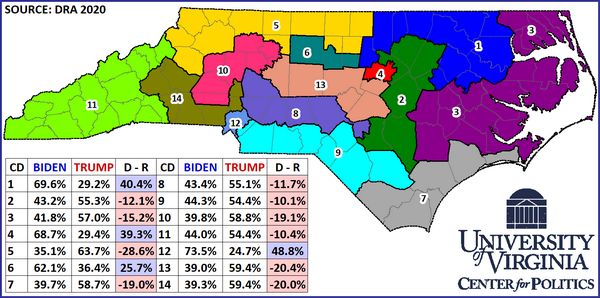

In any event, North Carolina is adding a 14th seat. If North Carolina Republicans essentially try to recreate something along the lines of a 10-4 version of their previous gerrymanders from the last decade, it’s not hard to imagine what they could do. Map 2 is a potential 10-4 Republican gerrymander.

Map 2: Hypothetical 10-4 Republican North Carolina gerrymander

As Map 2 shows, it is not hard to draw a plan that features 10 districts that went to Trump by double-digits. Republicans’ shakiest seat under this map would be NC-9, which Trump carried by just over 10%, though this is still a bump up from Trump’s 8-point edge in the current version. The 9th reaches into the blue-trending Charlotte suburbs to include the home of Rep. Dan Bishop (R, NC-9), but he retains heavily GOP Union County, and some reddening rural counties in the east. Bishop won a close special election in 2019, but was not considered a top Democratic target in 2020.

Democrats made a series attempt at unseating Rep. Richard Hudson (R, NC-8) in 2020, but he held on by nearly seven percentage points. Though he retains much of Fayetteville, the 8th moves further into the heavily GOP-leaning Piedmont.

On Map 2, the new 14th District is added in the western Charlotte metro area. It is rumored that Republican state House Speaker Tim Moore, who hails from Cleveland County, has his eye on a congressional run, so this may be a configuration he’d favor.

Democratic Reps. Deborah Ross (D, NC-2) and Kathy Manning (D, NC-6) each retain their bases, in Raleigh and Greensboro, respectively, but veteran Rep. David Price’s NC-4 is essentially dismantled. Price, who lives in Chapel Hill, would be drawn into a district that would geographically favor Manning. A map like this could prompt Price, who turns 81 later this month, to retire.

NC-1 as currently drawn is an interesting case: It became markedly less Democratic as the most recent map essentially unpacked it by removing Durham (though Map 2 puts Durham back into NC-1, that may ultimately not be the case). Butterfield and Biden both carried the current district by roughly 8.5 points. It’s not impossible to imagine the district being competitive in a bad Democratic year. Just like a few other southern districts with substantial minority populations (the district includes a number of rural counties that are majority Black) NC-1 is not growing. Going into the 2010 round of redistricting, NC-1 needed to pick up almost 100,000 residents — this time, it is the only North Carolina seat that needs to add population. Republicans may just end up being safest leaving it alone for legal reasons, and perhaps they will be able to compete for the district at some point in the decade anyway. Short of moving Durham back into the district, Butterfield’s best scenario would be picking up Pasquotank County (Elizabeth City) while dropping some red rural turf around Greenville or Goldsboro — this would nudge the district slightly leftward.

While Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R, NC-11) has become a major lightning rod in Washington, he should be fine almost regardless. In the initial Republican gerrymander in advance of the 2012 election, the GOP helped push then-Rep. Heath Shuler (D, NC-11) toward retirement by removing Democratic precincts from the liberal city of Asheville from his western Carolina district. Shuler was replaced by Mark Meadows (R), later one of President Donald Trump’s chiefs of staff. The most recent North Carolina map now has all of Asheville in it, but Republican performance in other parts of the Appalachian district has improved. When Shuler was last reelected, in a competitive 2010 contest, he did better in some rural counties than he did in Asheville’s Buncombe County. Today, aside from running up the score in Buncombe County, Democrats would probably prioritize limiting their losses in Henderson County — this ancestrally GOP county was Shuler’s worst in 2010, but Biden was the best-performing Democratic nominee in this growing county since Jimmy Carter, in 1976. Still, Cawthorn and Trump each carried the district by about a dozen points, so Republicans should feel fairly secure with a similar seat.

Overall, though Republicans could draw some creative plans, North Carolina is probably his is another state where they need to be careful about spreading themselves too thin — especially in growing metropolitan areas where Democratic performance has been improving, most notably the growing Greater Charlotte and Triangle areas.

TEXAS

Number of seats: 38 (+2 from 2010s)

Party breakdown in 2012: 24-12 R

Current party breakdown: 23-13 R

Most overpopulated district: TX-22 (Houston Suburbs/Exurbs: Ft. Bend/Brazoria counties)

Most underpopulated district: TX-34 (South Texas: Brownsville/Harlingen)

Who controls redistricting: Republicans

2012 control: Republicans

A mid-1960s scholarly article on gerrymandering has as part of its title “Dragons, Bacon Strips, and Dumbbells,” which are terms sometimes used to describe what heavily gerrymandered districts look like. There’s no shortage of these kinds of shapes in Texas, one of or perhaps the most consistently gerrymandered state in the country for many decades: previously by Democrats, now by Republicans.

Back in 1994, a year when Republicans won a majority of seats in the South for the first time in modern history (and the House majority for the first time in four decades), the Democratic gerrymander of Texas endured: Republicans won the aggregate statewide House vote by 14 points, but won only 11 of the state’s 30 seats (that aggregate vote is inflated, as Democrats left five seats uncontested while Republicans had a candidate in every seat, but this was still a clear gerrymander). In the Democrats’ 2018 national wave year, Republicans won 64% of the seats with less than 52% of the two-party vote (though the Republicans left four seats unopposed).

There’s no question that Texas has become a more competitive state at the presidential level in recent years. Mitt Romney won the state by 16 points in 2012, and then Donald Trump won it by only nine in 2016 (that was as the national popular vote contracted from Barack Obama by four to Hillary Clinton by two, so Texas became markedly less Republican compared to the nation as a whole). In 2020, Trump won the state by 5.5 points, meaning that Trump did about 3.5 points worse last year than he did in 2016.

This is evident across the state’s gerrymandered districts, many of which got much more competitive over the course of the decade as Republican strength waned in growing suburban areas across the state. Trump’s 2020 margin was at least 10 points worse than Romney’s 2012 margin in 15 of the state’s 36 districts. Moreover, the Republican slippage was apparent in the state’s close 2018 Senate race, when 20 of the 36 districts voted more Democratic than the state as a whole. Democrats, at both the presidential and congressional level, flipped two formerly Safe Republican seats by the end of the decade: those now held by Reps. Colin Allred (D, TX-32) and Lizzie Pannill Fletcher (D, TX-7). Biden flipped a third, TX-24, but first-term Rep. Beth Van Duyne (R) narrowly held it as an open seat last fall, and he came within three points or less of flipping seven more. In other words, the Republican gerrymander generally endured, but it was showing major signs of strain by last fall.

Though Texas is getting closer at the presidential level, it still pretty clearly leans Republican, and that’s a little more pronounced at the congressional level. In all 23 seats they won, the Republican House candidate got a larger share of the vote than Trump. Republican challengers also did better than Trump against the two new Democratic incumbents, Fletcher and Allred, which indicates a lingering Republicanism below the surface even in some districts that are clearly leaning Democratic now at the presidential level.

The Democrats did not gain everywhere in the state at the presidential level, though. Joe Biden’s 2020 margin was between 14-19 points worse than Barack Obama’s 2012 margin in three districts — TX-15, TX-28, and TX-34 — that cover South Texas, although the districts’ three Democratic incumbents all did at least a little bit better than Biden.

With 38 districts for Republicans to draw, and Democratic lawsuits a certainty, we’re not going to pretend to be able to handicap what might happen, other than to say that our expectation is that Republicans will come out of Texas with a bigger advantage in the delegation than they hold now. How much bigger? It’s hard to say. Still, there are some observations we can make:

— Many of the Republican-held districts where GOP performance eroded in the 2010s are, to borrow the term from above, “bacon strips” that extend out from major urban areas into rural areas and or link two urban areas with wide swathes of dark red Republican areas in between. Perhaps the most striking example of this is TX-21, held by Rep. Chip Roy (R). His district stretches from downtown Austin to northern San Antonio, while also taking in rural areas whose most famous inhabitant was President Lyndon B. Johnson. Republicans will want to strengthen many of these districts, or they risk losing them later in the decade.

— One way to do that would be to make some Democratic districts stronger, or even create a new Democratic vote sink or two to make the other districts more reliably Republican. For instance, Republicans may consider drawing a safely Democratic district in Austin as a way to protect several Republican incumbents whose districts currently cover parts of Austin’s Travis County. This is something the Republicans arguably could or should have done last decade, although it didn’t end up hurting them, as they held all their Travis County seats the whole decade despite some close calls. Tadeusz Mrozek, an Election Twitter mapmaker, drew a hypothetical Republican gerrymander that creates a new, heavily Democratic district in Austin but otherwise is designed to elect 27 Republicans and 11 Democrats statewide. Republicans may also decide that, instead of targeting Allred and/or Fletcher, they could just change their currently Democratic-leaning swing seats into very safe Democratic districts.

— In the Houston area, Rep. Kevin Brady’s (R, TX-8) retirement may be convenient for Republicans. While TX-8 takes in some rural counties, the heart of the district is Montgomery County, a veritable wellspring of Republican votes — in fact, it was the only county, nationally, that gave Trump a margin greater than 100,000 raw votes in both 2016 and 2020. Without an incumbent to consider, GOP mappers could unpack Brady’s 8th District to buffer up adjacent Republican districts.

— Depending on how enduring the Trump 2020 surge was among Latinos in South Texas — and this is an open question, although some signs of Democratic weakness in the region also appeared in Beto O’Rourke’s (D) otherwise impressive but unsuccessful challenge of Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) in 2018 — Republicans very well may try to grab one of those three South Texas seats. Rep. Filemon Vela (D, TX-34) has already announced his retirement from one of them.

One of the themes in public reporting about GOP gerrymandering efforts across the country is a push and pull between being maximally aggressive and grabbing as many Democratic seats as possible in order to ensure a 2022 House majority versus being a bit less aggressive and designing districts that can elect Republicans throughout the decade. Rep. Patrick McHenry (R, NC-10) summed it up in a quote to Politico: “There’s an old saying: Pigs get fat. Hogs get slaughtered. And when it comes to redistricting, that is, in fact, the case.” We’ll spare you any more reference to pig products and pig product production, as there’s been plenty of that in this section, although Democrats reading this are plenty queasy already.

Conclusion

Even if we assume only modest gerrymandering by Republicans — and that is not a safe assumption, but let’s make it here just for the sake of argument — it’s easy to see how Republicans could squeeze a half-dozen more net seats out of these four big states.

Republicans in Texas could, for instance, go from 23-13 to 25-13 just through making sure the state’s two new seats go to them, or some other combination of changes that gives Democrats a new seat but compensates for that by making an existing Democratic seat more Republican. Georgia Republicans could add a seat by altering one of the Democratic-held GA-6 or GA-7, making one markedly bluer and the other markedly redder. North Carolina Republicans could ensure that the state’s new seat is a Republican seat, and Florida Republicans could do the same while altering one other current Democratic seat, either FL-13 in the Tampa Bay area or FL-7 in the Orlando area, in such a way that a Republican wins it next year. So that would be six seats right there. And Republicans in these states probably will go further than this, with some of the possibilities outlined above, although doing so may carry more risk, particularly if Republicans stretch themselves too thin in big metro areas where their strength has eroded in recent years, most notably Atlanta, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Houston, Austin, Raleigh, and Charlotte. That we did not mention any Florida cities in that list — Republicans generally have held up better in that state’s big urban areas — is an indication that perhaps Florida represents the GOP’s best gerrymandering opportunity of this group, despite the state’s seeming restrictions on such activity.

We’re now through almost the entire South in our ongoing redistricting series — the only Southern state we haven’t touched on yet is Virginia, and the state doesn’t really vote like the rest of the South anymore anyway (we’ll tackle the Old Dominion in a future part of this series) — and the GOP’s redistricting dominance in the region is obvious. In the coming weeks, we’ll explore other regions where Democrats are better-positioned, or at least perhaps not-as-badly positioned, and see where Democrats might be able to make up some of the ground they appear poised to lose in the South.