| Dear Readers: Join us Thursday evening from 6-7 p.m. eastern for a conversation with Matthew Barzun, the former U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom as well as Sweden. Barzun will be discussing his experiences representing the United States abroad, his work as the national finance chair for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, and his new book, The Power of Giving Away Power: How the Best Leaders Learn to Let Go.

Andria McClellan, a member of the University of Virginia Center for Politics’ advisory board and a member of the Norfolk City Council, will interview Barzun following introductory remarks from Center for Politics Director Larry J. Sabato. To watch on Thursday evening, just click the following link: https://livestream.com/tavco/powerofgivingawaypower This is the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, which features short updates on elections and politics. Below, we react to Gavin Newsom’s victory in his recall election in California and take a look at the new proposed congressional map in Indiana. — The Editors |

CA-GOV moves to Safe Democratic following Newsom’s recall victory

It is going to take a while to get the final results in the California gubernatorial recall. But we know enough to say that the race was not at all close, and that Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) should not have any trouble winning a second term next year. So as the votes are still being counted in the California gubernatorial recall, we’re moving the regular election next year from Likely to Safe Democratic.

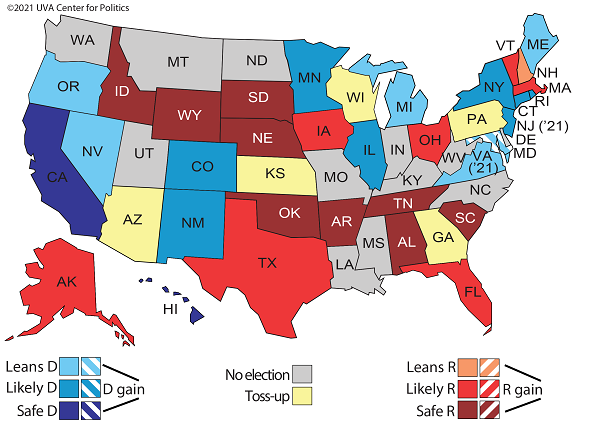

Table 1: Crystal Ball gubernatorial rating change

Map 1: Crystal Ball 2021-2022 gubernatorial ratings

As of Wednesday morning, the “no” side on recalling Newsom was leading 64% to 36%. However, that margin is likely to narrow as all the votes are counted, as the Democratic margin in the state did in 2020. The exit poll suggested that Newsom’s side prevailed by a little under 60% of the vote, which was similar to the aggregate of pre-election polls. We’ll wait and see what the final results end up being before diving into them too deeply. The size of Newsom’s initial victory in 2018 was 62%-38%. Our advice today: Do not be the person who makes sweeping claims about the granular details of an election in which the results have not yet been fully tabulated.

There were at least two significant factors that we thought had the potential to work against Newsom in this election that won’t be present next November. First of all, he did not have an actual opponent on the recall question — voters were asked to simply say yes or no on the recall. Yes, there was a second question asking voters to pick a hypothetical replacement — a vote that many Newsom supporters skipped — but this was not a straight head-to-head election. From our own experience following polls, incumbents often perform worse in a hypothetical question asking whether a person deserves reelection versus in a head-to-head matchup with a named opponent. In a sense, Newsom faced this kind of scenario in the recall, although it’s also possible that some Newsom critics voted no on the recall because they thought it went too far. Additionally, Newsom’s party label wasn’t on the ballot. While we doubt this mattered much — a governor is a well-known person whose party label should be obvious — California is a very Democratic state, and having a Democratic label next to one’s name on the ballot would likely be helpful.

Ultimately, Newsom benefited from the emergence of conservative talk show host Larry Elder (R) as his leading opponent, as Politico’s Carla Marinucci noted in a preview for the Crystal Ball last week. This likely helped him reinforce the salience of party in the recall and make it more of a choice election between himself and a far-right opponent as opposed to a referendum on himself.

Our bottom line here is that if Republicans couldn’t come close to beating Newsom in this unusual recall format, we doubt they have any real chance of beating him in a conventional election next year.

The apparent ease of Newsom’s victory has led some to question how much danger he actually was in. Polling was markedly closer in August than it was closer to the election. We kept our rating in the race as Likely Democratic for the entire recall. Although the format was different, the trajectory of this race was somewhat reminiscent of past Senate races in red states in recent years, where Republican candidates in states like Alaska, Kansas, South Carolina, and Tennessee all seemed like they might be in bigger trouble than they ended up being.

The lesson, perhaps, is that in this heavily partisanized era, majority party voters will eventually come home. But it’s easy to say that as an observer: It’s another thing for actual candidates and parties, who cannot just assume they will end up winning without putting in the effort to convert an electorate’s potential into actual results. Polling indicated an enthusiasm problem for Newsom earlier this summer, with the governor doing better among registered voters compared to likely voters in some polls. “It’s always been about motivating Democrats to take the recall seriously,” tweeted Los Angeles Times Senior Editor David Lauter last week. Newsom and national Democrats put in the money and work to accomplish that task. Vice President Kamala Harris and President Joe Biden campaigned in person for Newsom in the days before the election, and the Democratic Governors Association pumped in more than $5 million. That is not a gigantic expenditure for a huge state like California and it represented just a small percentage of the total dollars backing the anti-recall effort, but it represented real money nonetheless. National Republicans probably deserve credit for not chasing the shiny object in this race, as the Republican Governors Association only made what appears to be a minor investment.

Overall, we wouldn’t take much from this result about the political environment or assign the result much predictive value for the future. California is an extremely Democratic state, and Republicans there consolidated around a candidate (Elder) who was a bad fit for the state’s electorate. That said, Democrats can take heart in the fact that the result amounted to a dog that didn’t bark — had this race ended up very close, or if Newsom had lost, it would have been a bad sign for them. Naturally, not having to deal with an outcome like that is in and of itself a victory for Democrats.

Indiana releases draft congressional maps

Right on cue, as the Crystal Ball was concluding our nationwide redistricting preview series earlier this month, several states began releasing drafts of congressional maps. Yesterday, Indiana Republicans followed suit and put out their redistricting plan.

Indiana, where polls close as early as 6 p.m. eastern, is one of the first states to report results on election nights. Sometimes, its early returns set the tone for the rest of the night. Similarly, could the Hoosier State’s new map offer us any broader takeaways?

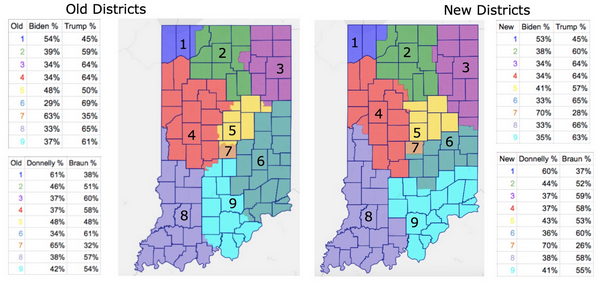

Map 2 shows the current and proposed map side by side. Using Dave’s Redistricting App, Nick Roberts, a local Democratic organizer, broke down the 2020 presidential and 2018 Senate results on the plans. On both plans, Democrats are favored in 2 seats to the GOP’s 7.

Map 2: Current vs. proposed Indiana districts

Perhaps one lesson from the remap is that just because a party can draw an aggressive plan doesn’t mean it will. Indiana Republicans, who hold both the governorship as well as firm majorities in the state legislature, could have concocted a plan that would have made reelection harder for first-term Rep. Frank Mrvan (D, IN-1) by splitting up his district. Instead, Mrvan retains a geographically compact Calumet Region seat that would have given President Biden 53% last year.

While Democrats are probably breathing a bit easier for now, Mrvan’s district, with its working class character, could be worth watching in future cycles. Lake County, which includes Gary, is IN-1’s most populous county, and it was traditionally among the most Democratic areas of the state — in 1984, it was the only county in the state that supported Walter Mondale. But its Democratic edge has eroded since then. If the proposed IN-1 were in place for 2000, it would have been a mirror image of the state: as Al Gore lost Indiana 57%-41%, he took about 57% in the district. Two decades later, as Biden lost the state by the same margin as Gore, he would have claimed just 53% in the new IN-1.

Still, Mrvan ran several points ahead of Biden last year, so assuming the final map is similar to this draft, we’d start IN-1 off as Likely Democratic.

Before this week’s draft map came out, it was obvious that a prime goal of the GOP mappers would be to shore up first-term Rep. Victoria Spartz (R, IN-5), who holds a seat in the northern Indianapolis area. The existing 5th District was drawn to be comfortably red, but by the end of the decade, some pro-Democratic trends were evident: in 2018, then-Sen. Joe Donnelly (D-IN) lost his job but carried the district — two years later, Donald Trump came close to losing it.

To shore up Spartz, Republicans took IN-5 completely out of Indianapolis’s Marion County. Under the current plan, almost 30% of IN-5’s votes come from northern Marion County — Donnelly carried that part of the district by 32 points. While the district is still anchored in suburban Hamilton County — the state’s fastest-growing and most affluent county — it reaches east to take in Delaware County, an Obama-to-Trump county that houses the city of Muncie. With these changes, the proposed IN-5 would have voted right in line with the state last year, going 57%-41% for Trump. Though the Democratic trends in Hamilton County may push the district more into play further down the road, we’d call this a Safe Republican seat for 2022.

With Spartz’s hand strengthened, the GOP did not have to do much to protect their other incumbents, although there were some interesting geographic changes. The 6th District, held by Rep. Greg Pence (the former Vice President’s brother), becomes smaller as it adds some closer-in parts of the Indianapolis metro. In turn, the 9th District, held by Republican Rep. Trey Hollingsworth, reclaims the Ohio River counties that it had before 2012.

In the southwestern corner of the state, IN-8 saw few changes. Known as the “Bloody Eighth” because of its historically volatile politics – it changed party hands a half-dozen times from the early 1970s through 2010 — the past decade in IN-8 was one of seemingly uncommon stability. After winning it in 2010, Rep. Larry Bucshon (R, IN-8) now routinely clears 60% of the vote — the “Bloody Eighth” is now just blood red.

While districts 2 and 4 both have Democratic college towns (South Bend and West Lafayette, respectively), those blue beachheads are overwhelmed by much redder rural and exurban swaths. Similarly, while IN-3’s largest municipality is Fort Wayne, a Trump-to-Biden city with 260,000 residents, the rest of the district gave Trump over 70%.

In short, if this draft is enacted, the most likely outcome would be a continued 7-2 GOP Hoosier delegation. Rep. Andre Carson (D, IN-7) has little to fear in his Indianapolis-centric seat and Mrvan would be favored in his light-blue IN-1 — but the 7 Republican seats would be firm.